Cover for Chaver-Paver, Labzik (mayselekh vegn klugn hintele Labzik) [Labzik: Stories of a Clever Puppy] (New York: IWO, 1935).

Yiddish Theatre is Child’s Play: The One-Act Repertoire Part II

Sonia Gollance

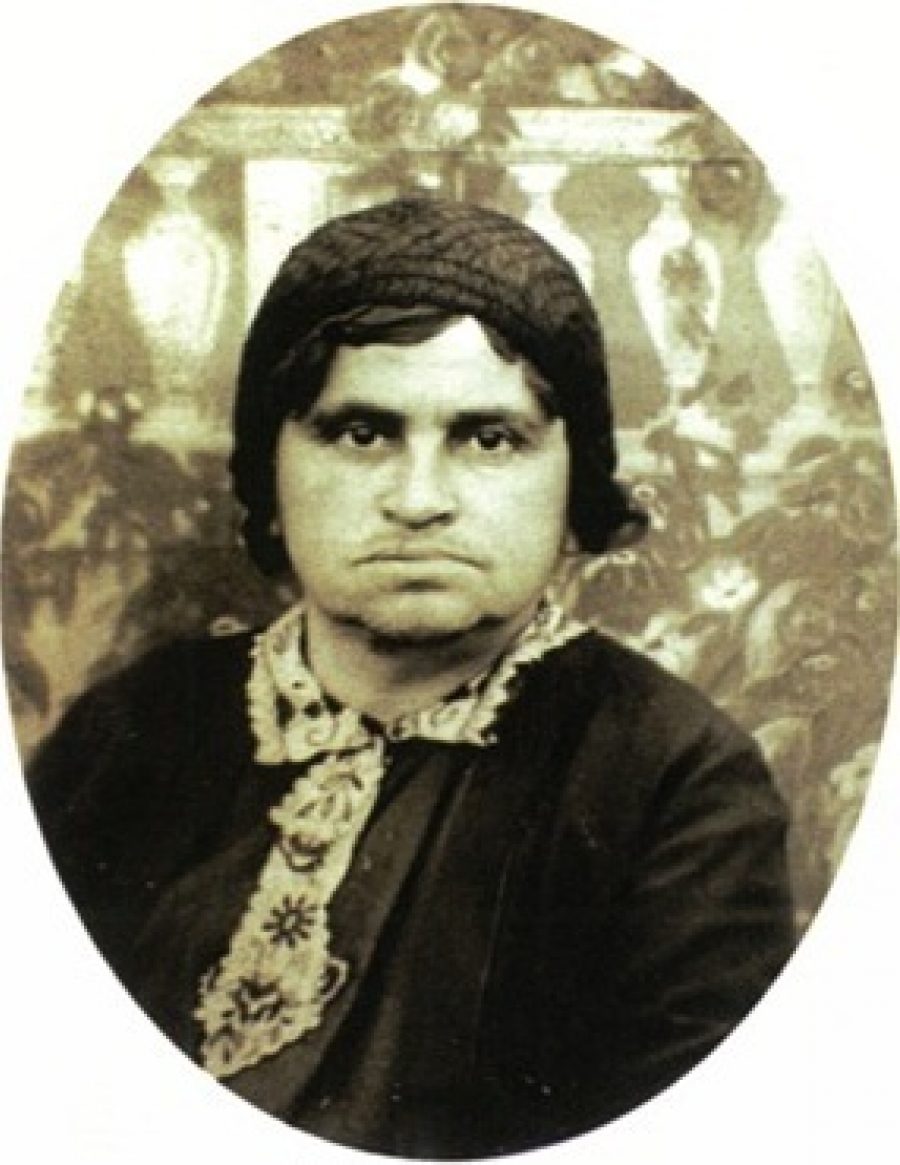

People don’t usually discuss Sarah Schenirer and Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman in the same breath. And why would they? Schenirer (1885-1935) was born to a Belz Hasidic family in Kraków, and ultimately went on to found the Beys Yankev network of schools for Orthodox girls (also known as Bais Yaakov). Remarkably, since it was established in interwar Poland, this education system continues today. Schaechter-Gottesman (1920-2013) was born in Vienna, grew up in Czernowitz, and was a member of a renowned family of Yiddishists. After immigrating to the United States after the war, she became a leading figure in New York’s Yiddish-speaking community. Among her many accomplishments, she was a poet, visual artist, a poet, songwriter, and playwright for children, cultural activist, and an educator. One might say that Schenirer and Schaechter-Gottesman represent opposite ends of the religious spectrum in terms of education in the Yiddish world. Schenirer designed the Beys Yankev schools to give Orthodox girls an alternative to having either a secular education or no formal education at all.

Sarah Schenirer

In contrast, Schaechter-Gottesman studied art, was trained at the Jewish Teachers’ Seminary, and taught at the secular Sholem Aleichem Folkshul and the Workmen’s Circle. Although the two women belonged to very different cultural circles, both are currently receiving renewed attention: Schenirer is the subject of a forthcoming book by scholar Naomi Seidman, which includes translations of Schenirer’s writings in Polish and Yiddish, and the National Yiddish Book Center conducted a successful crowd-funding campaign to produce a short documentary about Schaechter-Gottesman.

I’ve been thinking about Schenirer and Schaechter-Gottesman a lot lately because two of my fellow Digital Yiddish Theatre Project collaborators, Amanda Miryem-Khaye Seigel and Debra Caplan, were kind enough to send me photographs of Schaechter-Gottesman’s and Schenirer’s plays for children from the New York Public Library and YIVO Institute for Jewish Research respectively (thanks also to Itzik Gottesman and Janina Wurbs for their help in locating the Schaechter-Gottesman plays). A great deal of the time, even when I’m based in Germany, I’ve had little trouble accessing the various Yiddish plays I need for Plotting Yiddish Drama, thanks to the digitization efforts of the National Yiddish Book Center. And, indeed, if you peruse the catalogue of the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library, there are numerous plays for children, many of which are part of the Noah Cotsen Library of Children’s Literature. Many of these editions, like all sorts of children’s literature in Yiddish and other languages, come complete with engaging illustrations.

Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman. Photo courtesy of Itzik Gottesman.

Yet children’s plays were not necessarily published in book form or preserved for posterity. They may have been distributed to educators, designed for one-time school productions, and soon forgotten. Children’s plays are not a particularly prestigious genre, even if they serve an important role in communicating values and cultural literacy to the next generation. Indeed, numerous renowned writers created stories and plays for children. Nonetheless, few translations or works of literary criticism concern Yiddish children’s literature in general or children’s plays in particular; we’re excited about the new Kinder-Loshn-Publications initiative by Yugntruf Youth for Yiddish and hope they consider publishing some plays for children. Whether due to the status of children’s literature or women’s role in early childhood education (at least outside of a traditional kheyder school setting), many Yiddish plays for children were written by women. These plays were frequently published in pedagogical journals or booklets, the kind of ephemeral texts that are more commonly found in libraries or archives than in a digital library. And so I needed to write to my colleagues in New York to get the text of a 1929 Schenirer play that was published in Kinder bibliotek (children’s library) and two Schaechter-Gottesman plays that appeared in Pedagogisher buletin (pedagogical bulletin) in 1962 and 1964 respectively.

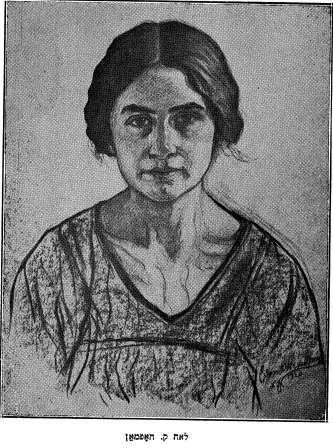

Our current Plotting Yiddish Drama (PYD) batch gives a taste of the Yiddish one-act plays that were written for children. While this group of six plays is certainly not exhaustive––and makes no claim of being representative––it suggests that certain themes may have been particularly popular in this genre. Some of these topics are not unique to Yiddish children’s literature, like the talking dog in Khaver-Paver’s A gesheft hob ikh! (I Don’t Give a Damn!). While a talking dog might have made more sense to American Yiddish audiences than to those in Eastern Europe, considering the historically complicated relationship Yiddish-speaking Jews had with dogs, writers of Yiddish children’s plays also brought many objects to life. Not surprisingly, considering the pedagogical aims of many children’s plays, Hebrew letters often sing and dance in a way that encourages young audiences to build productive associations, as in Leah Kapilowitz Hofman’s play Der khanike tants (Hanukkah Dance).

As this play suggests, quite a few children’s plays were designed to celebrate and teach children about Jewish holidays, including Hanukkah and Purim. While Schaechter-Gottesman’s A purim-shpil (A Purim Play) is an actual Purim play, including a short rendition of the Book of Esther, her play Dreydl-dreykop (Dreidel-Head) focuses on a dreidel’s identity crisis without explaining the story of the holiday itself. Schenirer’s Khane un ire zibn zin (Hannah and her Seven Sons) recounts a story from the Book of Maccabees, although this pious rendition has few of the quirky touches that animate other plays, like Esther Schumiatcher’s fanciful In tol (In the Valley). While this batch is in one sense more focused than other PYD installments, it offers many interesting opportunities for comparison, in part because it contains the first example thus far of a play designed for the religious needs of a pious audience.

Leah K. Hofman

Left to Right: Ester Shumyatsher-Hirshbeyn, Mendl Elkin, Perets Hirshbeyn, Uri-Zvi Grinberg, Khane Kacyzne, Alter Katsizne, and Esther Elkin.

While I’ve been thinking about Schenirer and Schaechter-Gottesman lately (especially considering Schenirer’s criticism of secular theatre as an entertainment for Jews), it is worth considering the lives and works of the other playwrights represented in this batch. Some, like Khaver-Paver and Hofman, are best known for their works of children’s literature. In fact, Hofman published the first Yiddish-language book of children’s literature in America. Others, like Schumiatcher (the wife of playwright Perets Hirshbeyn), are better known for their connections to Yiddish literary circles. Children’s literature gives us an opportunity to consider the inventiveness, values, and cultural goals of a group of playwrights who haven’t been featured in other PYD synopses. We invite you to read about their work, and perhaps even direct a purim-shpil or Hanukkkah play of your own.