Chana Pollack called "The Phantom Yiddish Writer," November 20, 2014, https://forward.com/life/209646/the-phantom-yiddis.... Courtesy: Forverts.

Excerpts from In Fayer un Flamen: Togbukh fun a Yidisher Shoyshpilerin (In Fire and Flames: Diary of a Yiddish Actress) by Shoshana Kahan (Part I)

Shoshana Kahan, Sheva Zucker

Translated and introduced by Sheva Zucker, edited by Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel for Women on the Yiddish Stage/Digital Yiddish Theatre Project

As a child Shoshana Kahan began reciting poetry and acting in plays in school. In 1908, she made her dramatic debut with the Harfe [Harp] troupe at the Groyses Teater as Manke in Sholem Asch’s Got fun nekome [God of Vengeance] and continued performing throughout her life, in Poland, Shanghai and America. In 1912, she married Lazar Kahan, a Yiddish writer, theatre person, and Bundist political activist, who would be her partner in many theatrical and literary ventures. In 1931 she, her husband, and the actor Morris Lampe, whom she mentions often in the memoir, took over the directorship of the Scala Theatre in Warsaw.

Kahan’s career as a translator and writer was no less prolific. She made her literary debut, according to Zalmen Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater, in 1915, with a translation in Lodzer folksblat of Mirbeau’s “Death of a Dog.” From 1924 to 1930, she published novels and contributed to the women’s pages of Yiddish newspapers in Poland as well as to the Polish Piąta Rana. She translated and dramatized many plays for the Yiddish stage, including Zind un shtrof [Sin and Punishment] by Zola and Farberovich’s Urke Nakhalnik.

A tour of Poland with a theatre troupe, begun in 1939, was interrupted by World War II. She and her husband fled to Vilna and then to Kovno in Lithuania. In 1941, they made their way through Siberia to Kobe, Japan, where Kahan performed on the very night of her arrival. At the end of 1941, the couple went with the Bundist refugee group to Shanghai. There, they lived in the ghetto from 1942 to 1945, continuing their theatrical work. It was this experience of Warsaw under siege, flight and, later, her life in the Shanghai Ghetto that Kahan described in her memoir, In fayer un flamen [In Fire and Flames], her only work to appear in book form. She published it in 1949 in Buenos Aires under the name R. Shoshana-Kahan, as part of the series Dos poylishe Yidntum [Polish Jewry].

At the end of 1946, after recovering from typhus, Kahan was brought to America with the help of Yiddish actors in New York, where she immediately became active as both an actor and journalist. She performed in the National Theatre in 1946, in Dos naye pleytim-teater [New Refugee Theatre], which she helped to create, and in Maurice Schwartz’s Art Theater in 1955. In 1957, she directed the Ensemble Theatre. She was among the first to write in the Yiddish press about the Nazi terror, and in 1946 published a series of articles about life in China in the newspapers Forverts and Der Amerikaner. Between February 1947 and October 1968, Kahan published twelve novels in the Forverts under the name Rose Shoshana with tantalizing titles like Far zeyere zind [For Their Sins] (1957), Ir mames sod [Her Mother’s Secret] (1954) and Ven a mame muz shvaygn [When a Mother Must Be Silent] (1949). She also edited a daily column for the Forverts, “Di Froy un di heym” [The Woman and the Home], under the name of Mary Rose. She died in New York City in 1968.

Translator’s note: In the forward to her book, Shoshana Kahan explains that she did not begin keeping a diary the day the war broke out, but a few days later, on September 5, 1939, because, “Early Friday morning, September 1, 1939, when the first bombs had already started falling on Warsaw, we still didn’t believe that war had actually broken out.” In the several pages before our first entry on September 13, she describes her separation from her husband, the Yiddish journalist Lazar Kahan, who is evacuated to Pinsk with a group of journalists, and her two sons, who leave with a group of friends to parts unknown. She then describes building barricades in Warsaw, the bombing of Warsaw, the hunger and devastation, and how life in Warsaw as she knew it comes to a standstill.

from WAR

September 13, 1939

The bombing is terrible. The house is shaking. The bombing is all taking place now, here, in the streets. Maybe we should run to another street? But where?

The neighboring house on Novolipki 24 has collapsed. The family of the actress Diana Blumenfeld lives there. Her sisters. We have to help them. I run down with my maid but we’re not allowed to come near them.

My brother-in-law comes running, more dead than alive. Warsaw is crumbling, the sky is red, as if the whole city were on fire… What does one do? Where should we run?

The actor Al. [Alyosha/Eliohu] Shteyn and his wife come running to me carrying a small child, sick with the measles. The child with frightened eyes. Al. Shteyn is wounded. They left everything and fled their burning building on Muranovske [Muranowska Street]. The actor Sheftel calls to find out if we need help. We tell him that our building is burning, all of Stavke [Stawka] Street is burning, the Nalevkes [Nalewki] and Genshe [Gęsia] Streets, too. People are running from their homes as if crazed. Many people are killed on the road by shrapnel.

That’s the Rosheshone present given to the Jewish neighborhood.

***

We run into the basement shelter. The big basement is densely packed with people, you can barely push your way through. ….

It’s a beautiful warm day outside but in the basement it’s wet and cold. …

People sit looking wearily at the exit. They’re thinking about how to stay alive.

When we enter the basement, the moods of those there get even heavier. I live on the first floor and I would seldom go down to the basement… In the basement you don’t hear the bombing as strongly. When people see me, they panic… Their sallow faces become ashen grey. Although I’ve been living in the building for fifteen years, I don’t know any of my neighbors.

I try to smile and say, “I came to see how you’re doing. And to wish you all a good year.”

“Happy New Year!” they all answer with tearful voices.

Soon the cellar dwellers see how the sick [actor Morris] Lampe is brought into the basement. Despair grows greater and people are starting to stir from their places.

I want to reassure the desperate people, so I screw up my courage and leave the basement, but a strong blow near my legs drives me back in. A bomb had exploded in a neighboring building. It hit so hard that our whole building shook and pictures fell off the walls.

From the basement you can hear shouting, “Medics! Valerian.” Everybody rushes off to his own little pharmacy… Every few minutes a woman faints…

The men in the basement sit, heads leaning on the wet walls. One jokester, apparently wanting to calm the frightened people down, says, “Folks, we already have the theatre here, we can have a performance… Hey, actors, it’s already sold out… A full house, why don’t we pull the curtain up?”

The house commander, a tall, lively man with an affable, kind face is running back and forth, trying to be funny, “Well, actors, why are you standing there? Either you perform or you give us back our money.”

But nobody is laughing… Nobody even cracks a smile. It could be that no one even heard the joke. Everybody is wondering where the bomb is going to drop now. Will it miss our building? Will we be spared?

“Well, what are you going to pray for?” the commander shouts, “After all, it’s a new year today!”

“Yes, a new year. Yup, they gave us quite the Erev Rosheshone,” says an older Jew. Some New Year’s Eve… God Almighty.” A great wailing can be heard from all sides.

Tuesday, September 26, 1939

… I start sobbing out loud. Is this Warsaw? I don’t recognize the streets. I don’t know where one street begins and where the next one ends. There’s a terrible smell of fire… Dead people are lying around on the ground… Severed arms… severed legs… How terrifying…

Now I’m on Byelenska Street (Bielańska). Once the “Novoshtshi” (Novelty) Yiddish theatre was here. A whole row of buildings has burned down. I want to find the spot where the building with the Novoshtshi Theatre once stood. And where is the building with the Hotel Krakovski?… I don’t know…

Suddenly, my companion [Meyer Vinder, a theatre impresario and journalist] cries out for joy, “ I know… where the theatre is… it’s this building. You see, a piece of wall with a fireplace hanging there, the owner of the Hotel Krakovski just renovated and built a fireplace…”

I can see it. From amidst a whole row of ruined buildings, there remains standing only a piece of wall with a wonderfully beautiful fireplace with Maiolica tiles…

The hotel was number 7. If that’s the case, then the burned down building next to is the “Novoshtshi” … we are standing in front of the theatre… We can see a few burned, singed remnants of the wall of a collapsed ruin.

The Yiddish theatre is no more…

Wednesday, September 27, 1939

Just walking down the street, I was told the sad news that our friend Daniel Shapiro, former artist of the “Vilner” [Vilna theatre troupe] was no longer with us… This strong, well-built man, this giant’s body was perforated like a sieve by a piece of shrapnel.

This is what they told me: “He had lain down for a while at his friend Grudberg’s (Yitskhok Turkov). Grudberg was sitting at the table, dozing and looking enviously at his friend Shapiro who was occupying his bed… And the shrapnel just happened to hit Shapiro… pierced him through the head. The poor soul suffered for a few hours and then died…”

Of all the people killed he was the only one for whom a funeral was arranged and who was buried at the cemetery.

October 9, 1939

In the evening, when it was dark, several actors gathered at my house to discuss what to do now.

It was decided that we had to flee, but how?

October 11, 1939

Today at daybreak, the actor Mikhoel Kleyn came to my place to tell me that they had decided to flee. They advise me to set out together with them. It’s a big secret. Nobody is supposed to know. We’ll have to steal across the border… People are saying that on the 15th of October, the Soviets will hermetically close the borders and then we won’t be able to smuggle ourselves in illegally.

“So many people are fleeing and they’re successful, we need to try, too.”

“No, my friend,” I answer him. “I won’t attempt it. I’ve stayed here to guard our home for my husband and children… I won’t abandon all of this… Besides, I don’t know where they are. I cannot desert my home. This is my address. This is where they will look for me.”

“What are you thinking?” Kleyn says to me. “They’ve arrested [Moyshe] Indelman, the editor. They’ll arrest the other writers… Later, after the 15th you won’t be able to flee. The Soviets won’t be letting anybody in…”

Lampe tries to explain to me that living like this is impossible… In Bialystok we’ll be able to work, we’ll earn money, we won’t be living in fear. The Soviets will receive us well… He can’t live without being able to go outside…. This is a slow death. He would have left a long time ago, but he didn’t want to leave me alone. But it’s impossible to wait any longer. Soon there will be no chance of leaving…

Translator’s note: Shortly thereafter, on October 13, Kahan gets word that her husband, Lazar Kahan, is alive in Vilna, and on October 20, that her two sons are alive in Rovno. Now she feels in a position to make plans to leave. On October 27, she learns that the Germans are issuing passes to allow people to leave. She and the actress Manyela, with whom she had been on a tour that was interrupted by the outbreak of the war, and Manyela’s son, obtain passes thanks to an incredibly helpful Polish official who concocts a story that they are actors who had come from Lithuania on a theatre tour. Their papers had been burned together with the theatre in which they had performed and therefore they should be allowed to return to Lithuania. Kahan was able to choose fourteen recipients of these “pasir-shaynen,” among them, herself, Manyela and her son and daughter, Morris Lampe, and her brother-in-law Yisroel Kahan with his wife and daughter. Despite reports that the road was dangerous and people were actually returning beaten and barefoot, staying seemed the worse option. On November 11, in the dead of the night, guided by a gentile driver, Kahan leaves with a group of twenty-two actors.

They travel through the Polish countryside seeing the devastation of war in towns and villages. They have a number of harrowing near-death experiences but miraculously, they escape alive.

from WE STEAL ACROSS BORDERS

Monday, November 13, 1939

When we had traveled approximately half a kilometer, the peasants on the road tell us that we shouldn’t go by way of the paved road, because there was still one bad guard stationed there, and not only that, you had to pass a lot of bad peasants… They advise us to go through the field… Since the field belongs to them they want to get paid for it… Money again… We give money and we continue on.

A young woman runs out of a house and begs us to have pity and take her with us… She’s been stuck in the house for three days and nobody wants to let her come with them because she has a small child… Since she recognizes us and sees another small child on the wagon, she pleads with the child’s mother to have pity on her and take her along. Her husband is also a performing artist…

“What’s your husband’s name?” I ask her.

“Haiblum… from Dr. Weichert’s studio, from Yung-teater (Young Theatre),” she replies.

“What? One of us,” says Lampe, “Quick, take your child, get on the wagon and sit down.”

The woman embraced us and kissed us. Seated on the wagon with her bundles and her child, she told us what she had been through, poor thing. For three days she lay in the house with her little child without so much as a drink of water. She traveled to the Bug River but because of the child, people were afraid to cross the Bug with her. Manyela takes a look at her own child and gives a deep sigh. Her eyes look at me with thanks. She too, poor mother, has lived through the same thing. People fear for their lives. Taking a child is risky… We travel to the last village. We are already at the Bug. The driver leads us to the village magistrate. We have to stay here until evening; when it gets dark the sailors will take us across the Bug. A price for every head was decided upon. Double what had been agreed on, but we can’t do anything about it: you have to pay… now everyone is extracting whatever he or she can get. We’re being fleeced. We take our coats off. Finally we’re in a house. We’ll warm up a bit and drink something. We’re tired and hungry. The magistrate’s wife serves us potatoes, for which we pay a pretty penny. Eagerly we take to the food. We haven’t had anything to eat for three days… The hot steam from the potatoes reminds us how hungry we are and we swallow them boiling hot… As we’re eating, just as I’m holding a hot potato in my mouth and burn my gums, the magistrate’s wife runs in screaming, “Quickly, quickly, run away! The police chief is coming.”

I run to the window and off in the distance I see somebody in a uniform riding… I gather my things quickly, shove them under the bed, get my coat and want to bolt… The magistrate’s wife yells, “You’ll ruin me… not through that door, through the kitchen door… the chief is coming.”

We run out quickly through the kitchen… We don’t know where to run, but we run… One of us runs into the bathroom, another into the stable… I hadn’t managed to make it to the stable so I run to some kind of a room… When I open the door of the room, from out of the shed comes a large, angry dog and he begins to tear at me and howl… But at that moment I was afraid of something that was even more dangerous than that dog…

… From the side, I see Manyela and little Lucia come out of the stable. The poor frightened child, she did everything she was told to do… Looking at the child, I don’t notice the chief standing on the doorstep of the house holding a riding crop and peering at us through his monocle… A chill runs through my limbs. The chief looks at my filthy clothes, a smile on his lips:

“What are you doing here?” he yells at us [in German], straightening up to his full height.

Manyela looks at me, and I at her. We are terribly frightened… We look around with fear lest the others, God forbid, crawl out of their lairs…

“We… we….” I stammer with fear, “we’re actors. We are on our way to Vilna.”

Manyela is completely shattered by fear. She bends down to kiss his hand, “Have pity on my child,” she pleads in German.

The man in the uniform strokes little Lucia and speaks, “How are you? I, too, am just a person.”

My God, if the Messiah had appeared at that moment, I could not have been more amazed than I was by those words. They gave me courage and I told him that we had been through a lot… We’re a group of actors… We are traveling to our husbands and dear ones… He shook his head feeling very sorry for us, “You unfortunate people,” he whispered.

That single word had such an effect on me that I burst out in a heart-rending cry. “Yes, unfortunate, and how!”

“Well, yes,” he continues, looking at us with such pitying glances… I will never forget the eyes of that good-natured, compassionate man.

“I’ll help you cross the Bug here,” he continues, “but what will happen on the other side? The Russians are shooting people who try to steal across the border… You must cross the Bug when the Russians can’t see you, when it’s dark.”…

“There won’t be any shooting today,” he says decisively and leaves. He is accompanied by three pairs of frightened and grateful eyes: mine, Manyela’s and little Lucia’s. The little one asks, “Mama, is he also a German? That good man?”

Again, we burst out crying for joy. Another miracle! God, continue to protect us!

They cross the Bug and dressed as peasants are driven to Semiatich (Siemiatycze) where they board a train for Białystok. At the train station there are throngs of refugees.

After putting something in our stomachs, we run to the train. Soon someone carrying a rifle comes running up to us.

“Shoshana, Lampe, what a sight you are. Our beloved actors!! Come, let me help you.”

My God! Where was that heavenly voice coming from? Such kind Yiddish words. And from someone with a rifle to boot. The words came from a Russian militiaman guarding the train, who had noticed us. He had once seen us perform in Warsaw. He took my bundles and carried them into the train… He congratulated us for having escaped from Hell.

… When we arrive in Bialystok we can’t walk through the station. People are lying around, swarming like ants. We stand there, it‘s so crowded we are unable to move, and on our lips there is a question, “And what now? Where do we go now?”

from BIAŁYSTOK

Wednesday, November 15, 1939

We list all the people whom we know in Bialystok, but none of them is very close to us. But suddenly I jump up for joy, how could I not have thought of this, there’s a Yiddish newspaper here, Dos lebn (Life) and newsrooms are open at night, and I also know so many people there: the editor Kaplan, Goldman, Sulkes, let’s go there right away. You’ll see how they’ll receive us, they’ll be so happy to see us.

Lampe, [the writer Dovid] Mitsmakher and I quickly get into a droshky and we’re off. The street is full of traffic, I’m literally astonished, it’s been a long time since I’ve seen a street at night. In Warsaw, everything is dead by four o’clock, but here the streets are full of Red Army soldiers and civilians.

When we drive past Sienkiewicz Street, another thought occurs to me, I ask the driver to stop the droshky and wait a few minutes. I jump off, because our friend Abrasha Kulbis lives here at the end of this street. He’s someone I could pop in on even in the middle of the night.

I knock, his little daughter answers me through the closed door, saying that her parents have gone to the wedding of the actor Videtsksy, and had locked the door.

I tell the little girl that I am Shoshana, that I’ve just come from Warsaw, that I’m going to the newspaper office and that when her parents come home they should come get me because I have no place to sleep.

I ask all the Jewish coachmen standing on the street corner if they might happen to know where the wedding of the actor Videtsky is being held, nobody knows. What a shame…. I had already started dreaming about a hot glass of tea. I sure could have used that.

So we proceed to the newspaper office, and I’m imagining how happy everyone will be to see me. We would rest a few hours and then Kulbis would come for me and put me into a warm bed… it’s no small thing – having friends like that.

At the newspaper office we are met by a man with a pale face. He looks at me with a questioning expression. “Who are you? What do you want?”

I look around and don’t see a single familiar face.

“I am Shoshana,”… but I don’t see him getting excited when I mention my name.

“I am the actress Shoshana. And this is the actor Morris Lampe and this is the writer Mitsmakher,” I say in a loud voice, in case he hadn’t heard me before.

He looks at us with the same indifference as before.

“I‘m finding this very disturbing and this time I say, in a depressed voice, “We are Yiddish actors and writers, we’ve fled Warsaw. We’ve just arrived, we have no place to go… I am the wife of the editor Lazar Kahan. Well, so we came here, to the office of the Yiddish newspaper, because we knew that it would be open at night.”

“Please, sit down, My name is Shulman.”

Soon many typesetters come running, one looked at me with tears in his eyes and sadly shook his head… Oy Shoshana, how you look… He shot a glance at his editor and remained silent.

“Where is Peysakh Kaplan?” I ask. “Where is Goldman?” The typesetter says nothing and leaves. I didn’t understand that one mustn’t ask…

I feel even more uncomfortable. We remain alone and all three of us look at each other.

There is a small sofa in the little room that is too small for even one person, but we all lie down on it. I wait for my friend Kulbis.

But Kulbis doesn’t come.

It’s already day. Their daughter probably forgot to tell them that I had come. We had to leave the newspaper office, but where should we go?

I go to the post office. I send two telegrams: one to my husband in Vilna and another to my son in Rovno, and then I go off to my friend Kulbis.

I enter unexpectedly. “Surprised you, didn’t I?”

“My husband is not here. When did you come?” asks Mrs. Kulbis as indifferently as if we had just seen each other yesterday.

My bones go cold. “Where is your husband?” I ask.

”My husband is at the theatre.”

“Kulbis is at the theatre? What is he doing there?”

“What do you mean, what is he doing there? He is the director,” she purses her lips.

“Kulbis?”

“Yes, he is the director of ‘otdiel isskustva’ [the art department].” She doesn’t ask me to sit down. She doesn’t offer me a glass of tea and I feel that my dreams about work are receding farther and farther.

“And what happened to your laundry? You had a laundry, didn’t you?”

“My husband is not a laundryman anymore. We got a new place to live. We’re moving out of here,” she says with pride.

I feel myself superfluous here. I leave quickly. It’s pouring outside. I feel like I will burst out sobbing loudly. I hide my face in my shawl, cover my mouth with it and cry loudly.

I’m seized by such a longing. To go back home… Let it be with the Germans, let it be with the devil, but in my own home, in my own little hut, with my own trash can and not like some stray dog.

Where do I go now?

People are lying on doorsteps, I walk through the marketplace; refugees are sitting on their bundles and the rain is pouring down, the cold is seeping through their bones. They sit there lonely, without a present and without a future, despair in their extinguished eyes.

My mouth is terribly dry. I’m embarrassed to go back to the newsroom, to Lampe and Mitsmakher. I’m embarrassed to tell them about my reception from my good “friends,” in whom I had put so much hope.

Friday, November 24, 1939

Today I saw my friend [the actor and director] Avrom Morewski who gave me regards from my husband in Vilna who is living at his place. …

After my conversation with Morewski, Libenson [head of the art department] called me over and told me that Morewski directed and organized theatre troupes; Viskind was his assistant. And so saying, Libenson added affably, “Morewksi knows you well so he will certainly give you appropriate work; you’ll be pleased with the work here in the Soviet Union. I can see that you have a lot of energy and we like that.”

“Certainly,” I say beaming, “Morewski knows me well.” I’m very happy, after all, I know in my heart that Morewski is aware of my stature in the theatre and he’s seemingly been one of my best friends for years. He will certainly want things to go well for me and to help me find a home after all my wanderings.

I write a few letters to friends, run to the coffee house to mail them, I’m in good spirits. I say good-bye to my son [who is going to study in Lemberg (today Lviv)], shove a hundred ruble bill into his hands. My last one. He doesn’t want to take it. “Mom, use the money to buy yourself milk and butter, you’re very weak.”

“My child, seeing you has restored me to health. I no longer need milk and butter. Morewski is the director of the theatre. He’ll take care of me. Go, go in good health, I’m feeling good today.”

“Yes, Mother,” he says, “the fact that Morewski is here in Bialystok makes it easier for me to leave. I know I’m leaving you among friends, he’ll surely take care of you.”

Saturday, November 25, 1939

Alone again. Lampe walks around distracted and upset. He can’t envision finding any suitable work.

Today I spoke with Morewski about the theatre.

“Don’t think, Shoshana, that this is Poland. You’re in Soviet Russia. You can’t be what you once were over there.”

His tone, his way of speaking freezes my blood. There was that officious tone again. Kulbis Number 2.

“I know,” I say, “I know that I can’t be what I was in Poland, but what good are these long prefaces? Tell me what you have to tell me…”

“I want to tell you, that there can be no talk of your having starring roles.”

“I’m not talking about being a star, but I think that you’ll give me my appropriate place in the theatre.”

“Appropriate place?” he answers, acting like he doesn’t understand. You absolutely have to forget about acting with Morris Lampe, just forget about that. He is a very good actor, he will certainly work, but whether or not he will work in the theatre, I don’t know.”

“Morewski, Lampe, and I have been performing together for ten years. In Warsaw we lived through so much together. He took his last bit of food from his mouth and gave it to me. He has no one. He is alone. I don’t want you to separate us. I know that the two of you had a falling out, but now is not the time to settle accounts. We can perform together and take the places we deserve.”

“There can be no talk of places, if you want to become a member of the company like all the other members, then, I suppose, you will get work.”

“Goodbye, Morewski, what you’ve said and how you said it, is enough. Adieu.”

I left. I ran through the streets as if being chased.

Kulbis… Kulbis Number 2.

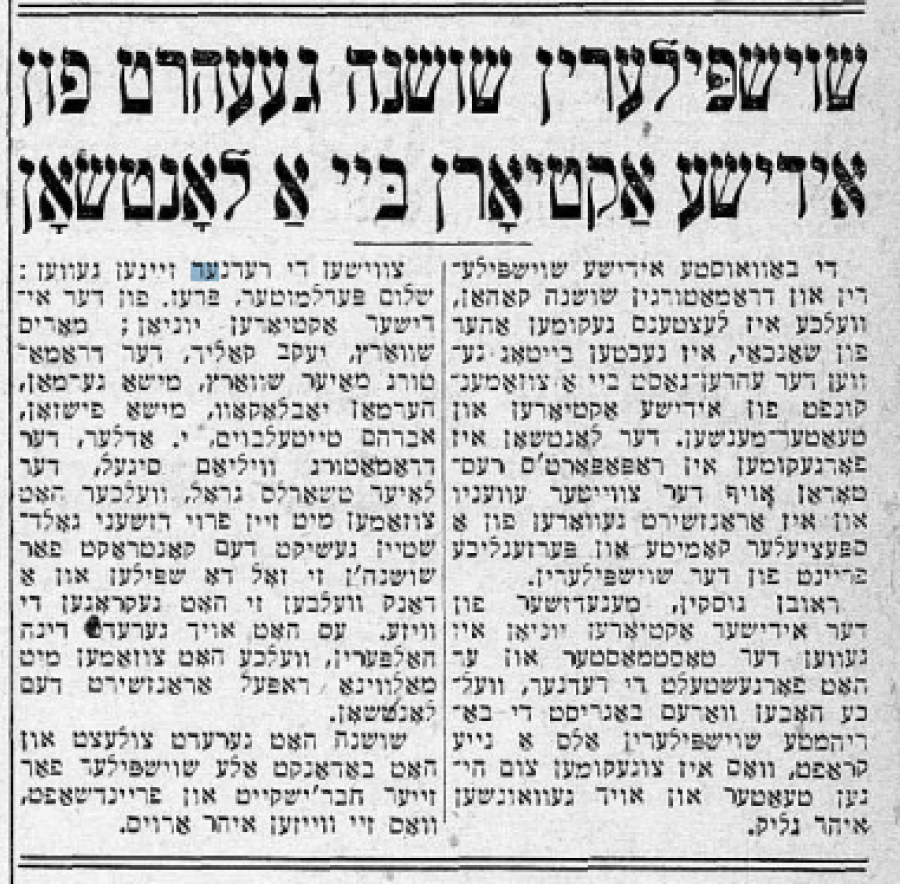

“Actress Shoshana honored by the Yiddish actors at a luncheon,” Forverts, November 15, 1946, 12.

Monday, November 27, 1939

Today, Lampe and I discussed the need to leave, unless we can accept the fact that Morewski and Kulbis will walk all over us. We must go out into the world. Not accept work here but rather go to Vilna which is neutral and where we can have contact with the outside world. We can either go through Lemberg or enter Romania through Shnyatin. We must look for ways and possibilities of leaving.

Tuesday, November 28, 1939

Today, a telegram arrived from a group of writers in Vilna saying that they were sending people to make contact with Paula Prilutski [writer and wife of philologist Noyekh Prilutski], Esther Elboym [wife of Yiddish writer Moyshe Elboym], Mrs. Neyman, [Yiddish literary critic Yeshua] Rappaport, [Yiddish lexicographer and editor Zalmen] Reyzen, and Shoshana.

We understood that this meant they were going to send us to Vilna.

I rejoiced. Thank God! But in my heart I was afraid. Yet again I would have to steal across borders.

Translator’s note: On November 28, 1939, Kahan left Bialystok to do exactly that, and after several harrowing experiences she arrives in Vilna on December 5, 1939 and is reunited with her husband.

from VILNA, JERUSALEM OF LITHUANIA

December 8, 1939

In Vilna I felt as if I had been reborn. I was in a familiar environment again, met a lot of people I was close to. A fine home had been set up to house literary refugees. A relief committee was established, everyone was received with love and concern. There was a feeling of family….

A nice kitchen had been set up where people would get together every day. We felt almost as if we were at Tlomatske 13 in Warsaw [the home of the Yiddish Writers’ Union]. Nobody felt demeaned by eating at the expense of the committee. We only felt pained by the fate of our poor families who were at the mercy of the murderous Nazis.

December 12, 1939

Today actor friends organized a banquet at Franya Winter’s house in honor of my arrival. I informed everyone about the dire situation of our friends in Warsaw. The actors hoped that with my coming we would organize a [professional] theatre, because now mostly amateurs were performing. We rose to observe a moment of silence in memory of our colleague Daniel Shapiro who had perished.

December 15, 1939

Today, the theatre director Boris Bukants and his wife, the actress Zheni Yaroslavska, whom we call Zlatke, came from Kovno to see me. We had been very good friends with them and amazingly – in this case, friends have remained friends and they were so happy to see me. Yesterday the director of the other Kovno theatre, Rashel Berger, was here. Both are offering me good conditions and I’m starting to feel better… It’s no small matter to be performing again… Today I sent a telegram to Argentina to Lampe’s friend, the theatre director Mide, exhorting him to try to bring Lampe, my husband, and myself to Argentina.

March 17, 1940

On March 3 I came to Kovno to act in and direct my play Bashke. I went into Café “Monika” and met [the Yiddish writer Zusman] Segalovitsh. We hadn’t been speaking to each other for a few years but who remembers things like this now. We were so happy to see each other. The first performance took place at Bukants’s theatre. After seven months of not performing it was a holiday for me.

March 28, 1940

Today we are in Olita [Alytus, a city in Lithuania about 67 miles from Vilna]. We’re supposed to perform Bashke. I would have given anything to get out of today’s performance. I didn’t eat all day, just stayed next to the telephone. I wanted to hear the news that my children had been released. Today was the judgment day… I kept phoning Vilna, calling the lawyers, who had so solemnly assured me that the children would be released, and before I went on stage I received the sad news that the children had been thrown back across the border again. So much for that promise… Now they’ll be caught again, this time by the Soviets, and they’ll arrest them for stealing across the border… And so we are hunted down and tormented.