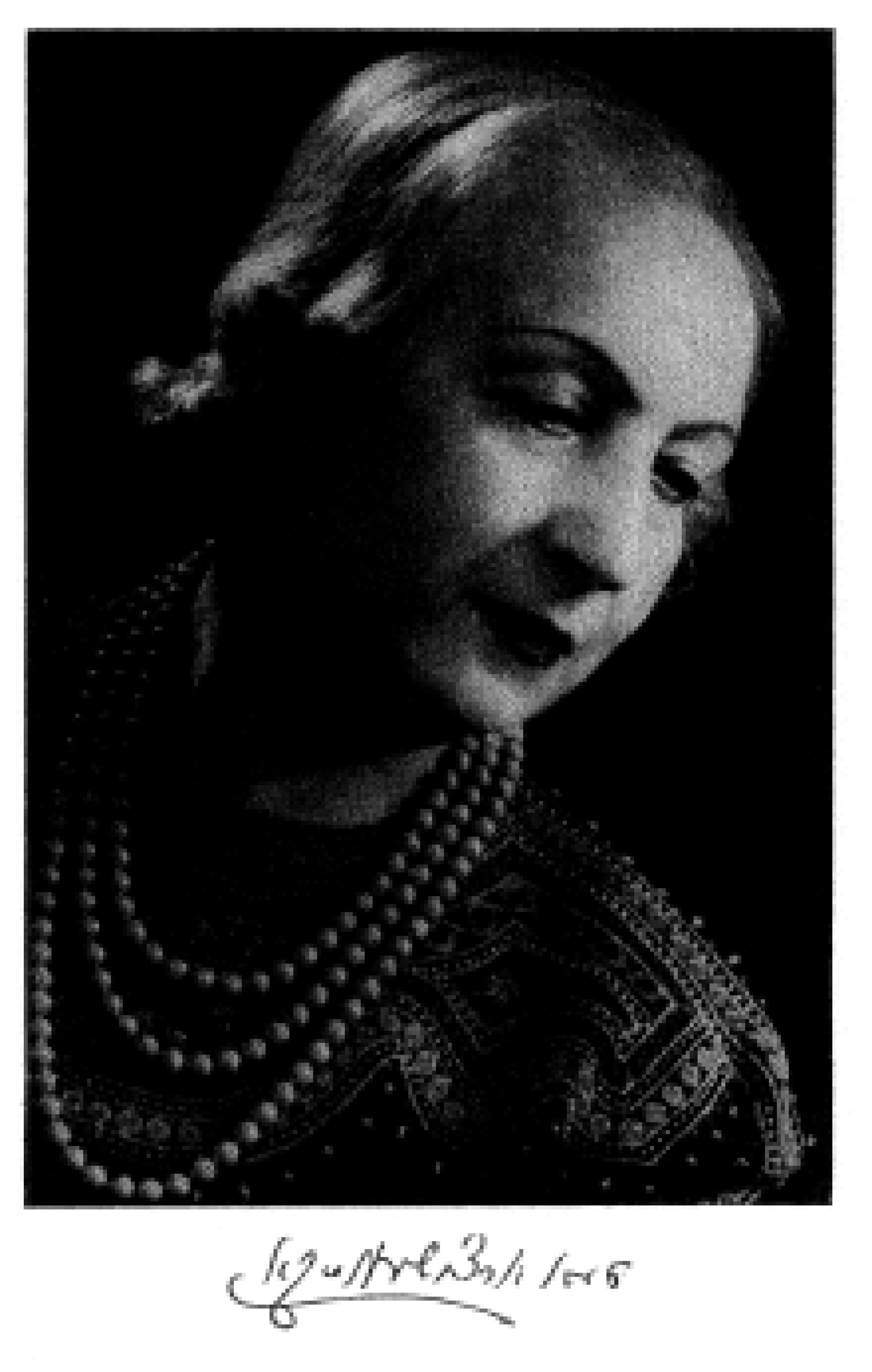

Image of Arciszewska from the 1958 edition of Miryeml

Tea Arciszewska: Remembering the Modernist Playwright on Her Sixtieth Yortsayt

Sonia Gollance

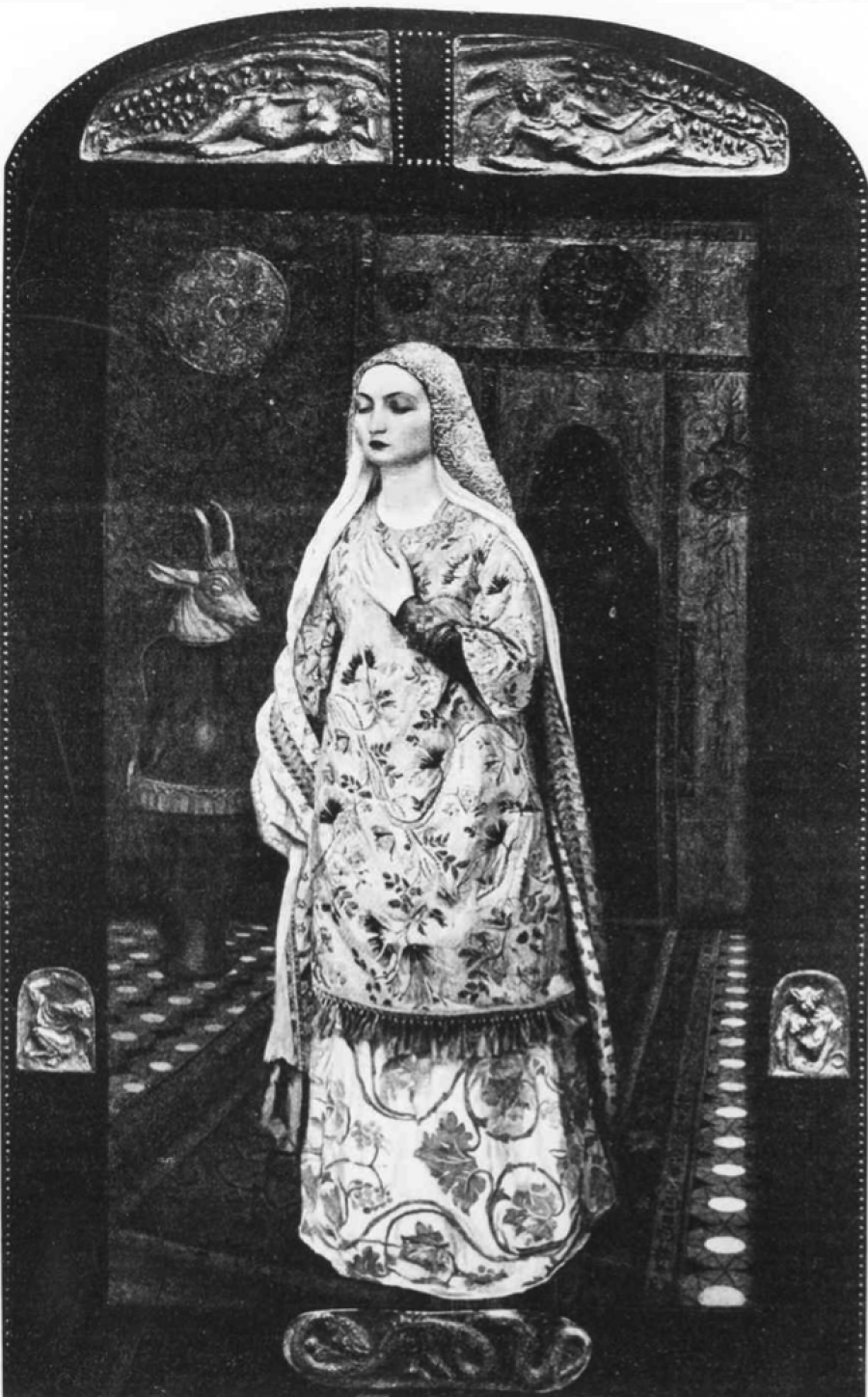

Sixty years ago today, the Yiddish playwright, actress, theatre company founder, and salonnière Tea Arciszewska (c. 1890 – 1962) died in Paris. Although she is now almost completely forgotten, Arciszewska was a mesmerizing and unforgettable figure in the Warsaw Yiddish culture scene, on account of her many Yiddish theatre achievements and her participation in Yiddish literary circles, as well as for her life as a bohemian. As Mark Turkow put it in 1954: “She deserves to have a whole book written about her; owing to her immense accomplishments in Yiddish cultural life in Poland, thanks to the assistance she rendered Jewish artists in Poland over the course of many decades, and—why deny it?—also due to the tempestuous, romantic life she led.” 1 Yet although Rafael Federman, in his memorial piece for Arciszewska in the Forverts (Forward) for her first yortsayt in 1963 opines: “the talented artistic personality [Arciszewska] does not deserve to be forgotten by the Yiddish culture world,” 2 Arciszewska is virtually unknown today. To the extent that she has been written about by the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project, it has primarily been for her work as an artist’s model for Maurycy Minkowski, and this brief mention is one of the few references to her contributions in English. My goal, in this piece and in my larger, ongoing project to translate her play Miryeml, is to restore Arciszewska to her rightful place in Yiddish theatre history.

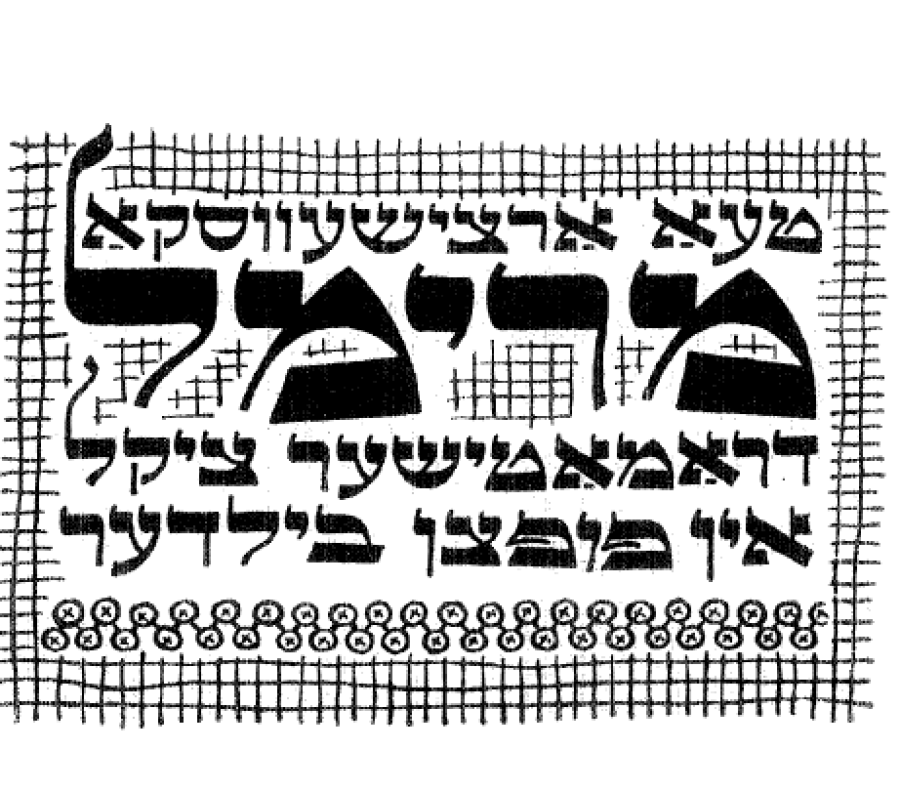

Title page for the 1958 edition of Miryeml

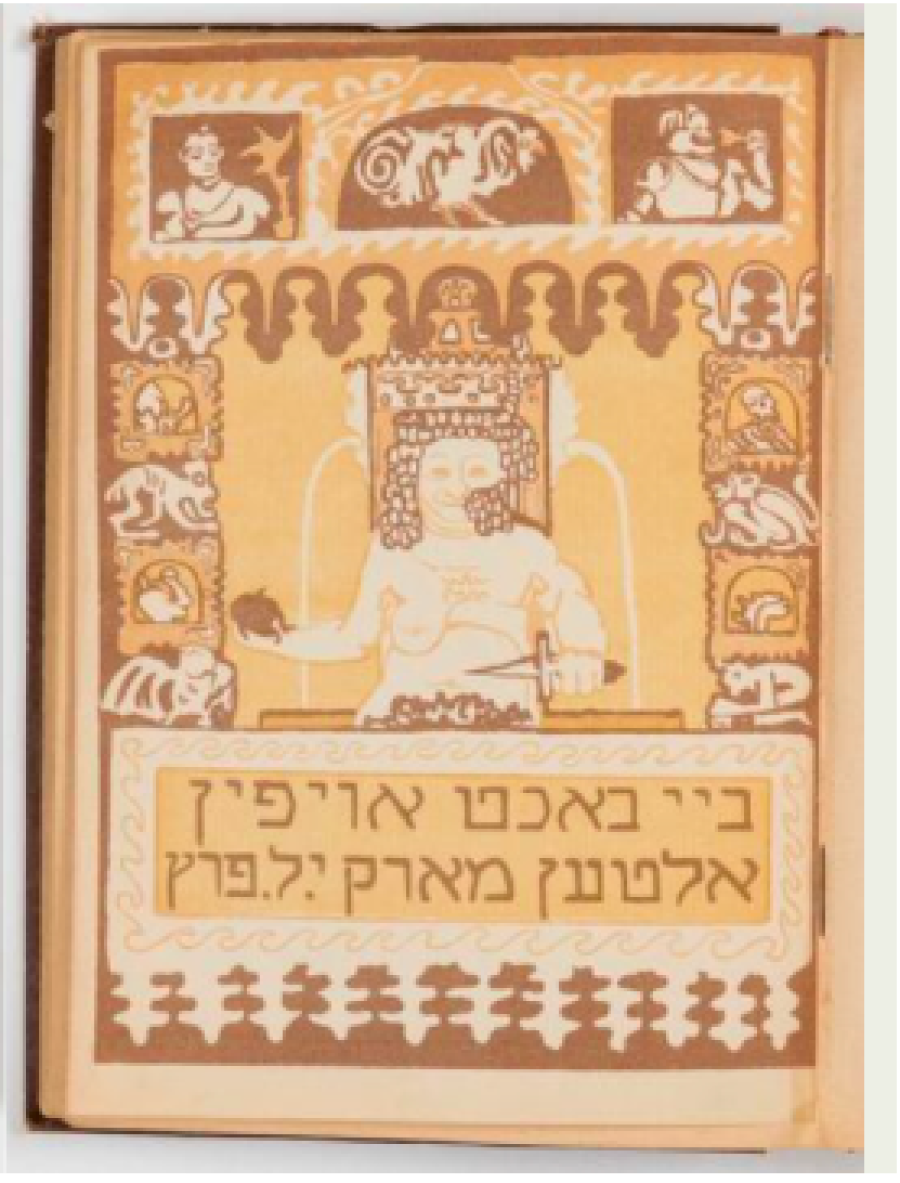

Arcizewska was born around 1890 to the Lipski family, illustrious Ger Hasidim, in a shtetl called Mława in Congress Poland. Despite the pious family environment, she and her two older sisters each pursued a career in the arts: Sara Lipska became a painter and Liba a dancer. At age sixteen, Arciszewska met her first husband, the artist Szymon Kratka and, in the face of her family’s disapproval, the young couple eloped to Palestine and spent several years there while Kratka attended the newly-created Bezalel art academy. 3 The Kratkas 4 then moved to Warsaw, where they became part of I. L. Peretz’s renowned literary circle. In his epic, seven-volume memoir of Jewish literary life in early twentieth-century Poland, Y. Y. Trunk devotes two chapters to the couple, whom he regards as exotic on account of their travels–and perhaps also due to Arciszewska’s exceptional Hasidic pedigree. He describes the sensation created by Arcisewska (or Tocia, as he calls her) 5 :

Not many ladies or interesting women would visit Peretz. Yiddish literature was never considered respectable by the women from bourgeois and educated circles of Polish Jewish society. People still looked down on it and saw culture and beauty only in Polish writings. Nevertheless, there were exceptions…Tocia seemed to eclipse [the other women in Peretz’s literary circle]. Truly, in her person a Jewish muse had descended from the heavens.

Arciszewska was one of the few women in this social set, and a number of her contemporaries claim that the teenaged bohemian became a muse to Peretz, who was nearly four decades her senior. In his book, Yitskhok Leybush Peretz un dos yidishe teater (Yitskhok Leybush Peretz and the Yiddish Theatre), theatre critic Alexander Mukdoyni claims that she “was the personification of the Polish-Jewish woman in his dramas.” 6 Peretz recruited Arciszewska as an actress for his project to create a more artistic Yiddish theatre company, and gave her the stage name “Miryem Izraels,” which she used, starting in 1910, as she performed in plays such as Peretz’s S’brent (It’s Burning). In 1925, she founded the renowned kleynkunst Azazel theatre troupe, in collaboration with such talents as director Dovid Herman, the first director of S. An-sky’s play, Der dibuk (The Dybbuk), a great hit of the Vilna Troupe.

Szymon Kratka illustration of Peretz’s Di goldene Keyt. Coutesy of the Yiddish Book Center.

Maurycy Minkowsky painting of Arciszewska as Esterka

Arciszewska’s male contemporaries wrote intriguingly—and often titillatingly or condescendingly—about her participation in this artistic milieu. Her princely Hasidic background–prominent Ger lineage on her father’s side and Alexander pedigree on her mother’s–fascinated them. They generally stressed her relationship to Peretz. She is often referred to as the wife of her first husband, Szymon Kratka, and called merely by the nickname “Tocia” (without a last name) or “Madam Kratka” (without a first name). They often emphasize her physical appearance (her refinement, her delicacy, a voice some judged as too weak for the stage) and discuss her highly individual style of dressing, which was regarded as both tasteful and aware of Jewish aesthetics, since she wore exotic or antique elements that added to the perception that—as inspiration for Peretz and artist’s model for Minkowski—she was the embodiment of a kind of Jewish womanhood that was appealing for advocates of a Yiddish cultural renaissance. Unfortunately, I have not (yet) found any of her own writings from this period, or any accounts by female contemporaries.

After surviving World War II, Arciszewska moved to Paris and finished her play Miryeml, which she had begun before the war and originally dedicated to a daughter who died in childhood. Although Arciszewska wrote other, shorter pieces that she published in the magazine Far undzere kinder (For Our Children) and in an almanac published by the Association of Yiddish Writers and Journalists in France, this play is unquestionably the work that defined her literary career. Even critics such as Melech Ravitch, who had previously maintained that she barely knew Yiddish, wrote glowingly of this play, which he claimed kept Peretz’s legacy alive and (in contrast with an earlier draft from the 1920s) now had a “flawless” form. 7 In 1954, Miryeml received the Alexander Shapiro Prize for best Yiddish drama from the World Jewish Culture Congress. Yankev Shatzky, in his speech at the event, compared Arciszewska’s artistry to the writing of modernist playwrights Maurice Maeterlinck, Peretz, and Stanisław Wyspiański. In 1958, the play was published in book form in Canada by Melekh Grafshteyn, with an introduction comprised of three letters by American Yiddish modernist Joseph Opatoshu (who came from the same town in Poland as Arciszewska and had passed away in 1954). N. Sverdlin raved about the play: “As soon as I received a copy of the book, I sat down to read it, read and could not tear myself away from the powerful drama of the destruction of Polish Jewry, which is portrayed with a dynamic tragedy and a poetic romanticism.” 8 Another edition was printed in Paris by Goldene pave in 1959, just one year after the Canadian edition. Miryeml was honored by the gatekeepers of Yiddish literary taste. This recognition is particularly striking because so little attention has been paid to plays written by women in Yiddish. And yet, Miryeml is virtually unknown today.

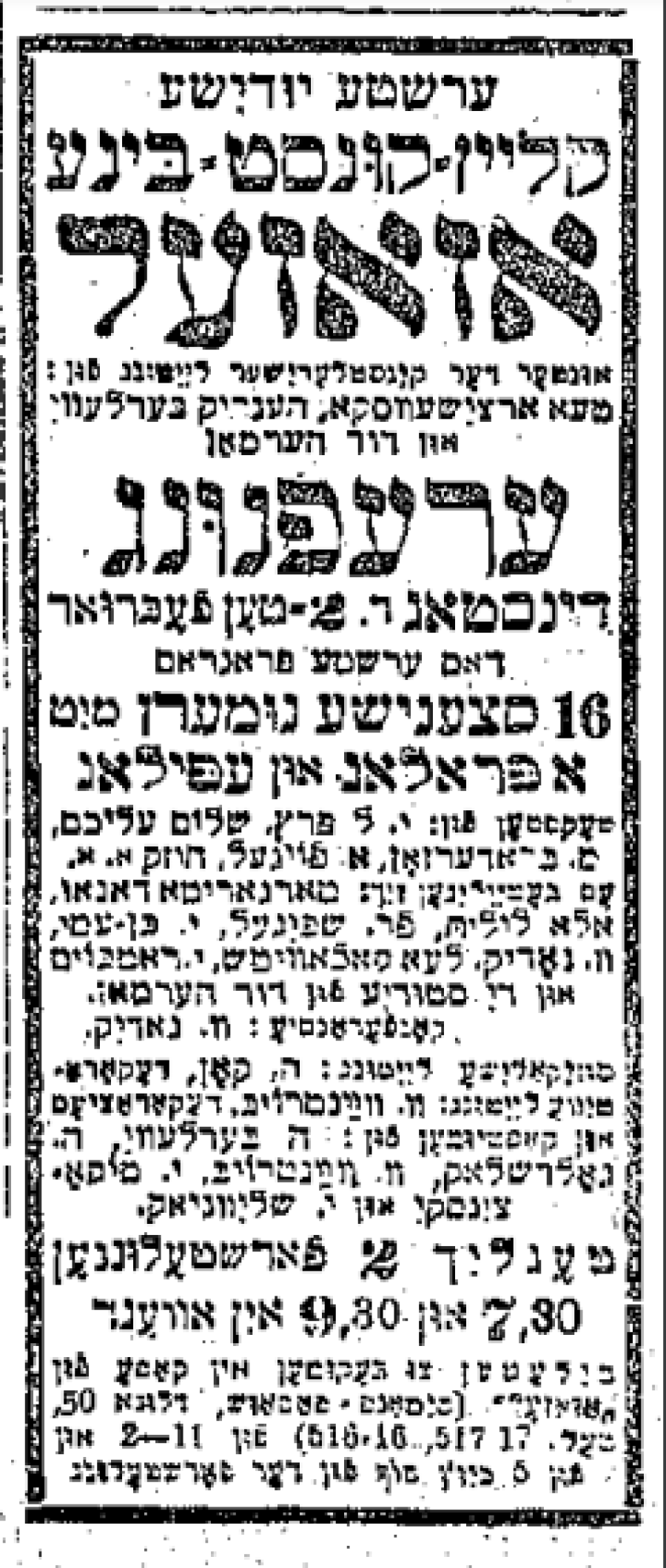

Advertisement in Haynt for the Azazel theatre troupe, which says it is under the artistic direction of Tea Arciszewska, Henryk Berlewi, and Dovid Herman (February 2, 1926)

In my work editing Plotting Yiddish Drama, I have access to dozens of synopses of canonical and more obscure works of Yiddish drama. I have not yet encountered anything like Miryeml. Anthologies of Yiddish writing about the Holocaust rarely include dramatic works. Yet Miryeml stands out even in comparison with other post-war Yiddish plays about the Holocaust, 9 since Miryeml’s topic and style of narration are unique. Miryeml is a dramatic cycle in fifteen scenes about the Holocaust from the perspective of Polish Hasidic children, who make sense of their circumscribed reality through games and stories about rebbes. The play takes its name from the character Miryeml, an orphaned thirteen- or fourteen-year-old whose father was a dayan (judge in a religious court). She suffers from a mental illness and often disturbs the other children with her morbid comments, which are frequently delivered in rhyme. By the end of the play, Miryeml becomes a prophet-like figure, who leads the children from Warsaw towards (she claims) Jerusalem.

While most Yiddish play translations are from the heyday of Yiddish theatre from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries, Miryeml is a post-war work that juxtaposes Jewish folklore with modernist motifs. It is also unusual for a text about the Holocaust, since it is a play that highlights the experience of a female adolescent with a mental illness. Another surprising feature is that it is very vague about who precisely is persecuting the children and why they need to hide in cellars for large portions of the play. Although it is not always obvious from the text how directly Arciszewska wanted to address the Holocaust, it is clear that Opatoshu viewed the play as a response to the khurbn (the Yiddish word for Holocaust), since he wrote in a 1953 letter to Arciszewska: “You have written something powerful… I have not encountered such images and scenes in the dozens of books which have already been written about the Holocaust.” 10 With regards to its modernism, topic, and critical acclaim, Miryeml challenges our expectations of Yiddish dramas and Yiddish women’s writing.

In February 1962, the Forverts published an obituary of Arciszewska by Paris correspondent Léon Leneman. In addition to recounting her life and praising her play Miryeml, the obituary also sharply criticized the involvement of the communist Kaganovsky Committee, which insisted (as a condition for fulfilling Arciszewska’s wish to be buried next to her last partner, the writer Efraim Kaganovsky) that their representative Dr. Sloves (presumably playwright Henri Chaim Sloves) deliver a eulogy. 11 The fact that her funeral seems, in certain respects, to have become a Yiddishist Cold War battleground simply serves to highlight the extent to which Arciszewska was so well connected with Yiddish cultural figures and Jewish organizations throughout her life. The obituary also includes the final stanza of her last, mournful poem, “Di zilberne laykhters” (The Silver Candlesticks), which she had published in 1961.

In honor of the life and yortsayt of this neglected dramatic writer, who to my knowledge has no archive, I conclude with my translation of her final verse here 12 :

,טייערע לייכטערס פון מיין אַלטער היים

װען איר װאָלט

געקאָנט זעהען און הערען… איר זעהט

,נישט לייכטערס

װי עס לעשט זיך אויס מיין לעבען… און

–װייסט נישט

,אַז באַלד װעט איר שטעהן לעבען מיר

און די ליכט

װעלען טריפען שטיל… מיט פאַרגליװער־

…טע טרערען

שטילער און שטילער… ביז אייביג שטיל

…װעט שוין װערען

Dear candlesticks from my long-ago home,

if you wanted

You could see and hear… You don’t

see candlesticks,

How my life is blown out… and

don’t know–

That soon you’ll stand by me,

and the light

Will drip quietly… with congeal-

ed tears…

Quieter and quieter… until it has become

eternal quiet…

Notes

-

1Mark Turkov, Di letste fun a groysn dor: geshikhtlekhe epizodn un perzenelkhe zikhroynes vegn yidishe mishpokhes in Poyln (Buenos Aires: Tsentral-farband fun poylishe yidn in Argentine, 1954), 286.

-

2Rafoel Federman, “Miryem Izrael – Tea Arciszewska,” Forverts, February 22, 1963, 10.

-

3In Yiddish theatre circles, Kratka is best known for designing the tombstone of celebrated actress Ester-Rokhl Kaminska.

-

4The name Arciszewska comes from her second marriage. I use this name because it was the name used for her published work.

-

5Yehiel Yeshaia Trunk, Poyln: zikhroynes un bilder, vol. 5: Perets (New York: Farlag “unzer tsayt,” 1949), 58–9.

-

6Quoted in: Zalmen Zylbercweig, Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 6 (Mexico City: Elisheva, 1969), 4884.

-

7Quoted in Zylbercweig, Leksikon fun yidishn teater, 4888.

-

8Quoted in Zylbercweig, Leksikon fun yidishn teater, 4888.

-

9For instance, Chava Rosenfarb’s Der foygl fun geto (The Bird of the Ghetto) or the dramatic adaptation of Zvi Kolitz’s Yosl Rakover redt tsu got (Yosl Rakover speaks to God).

-

10Quoted in Zylbercweig, Leksikon fun yidishn teater, 4887.

-

11L. Leneman, “A merkvirdike froy iz geshtorbn in Pariz,” Forverts (February 5, 1962): 2.

-

12Leneman, “A merkvirdike froy iz geshtorbn in Pariz,” 2.