Auguste Rodin, Danseuse cambodgienne de face (1906).

One (Act) for the Show

Sonia Gollance

One of the pleasures of reading Yiddish literary critics and theorists from a hundred years ago is the way they talk about why Yiddish culture matters. Their explanations are confident, they write with conviction, and they use colorful language to compare Yiddish texts with different artistic mediums and works of literature. On a recent research trip to Paris, I was sitting in a café reading Alexander Gordin’s introduction to a volume of his father Jacob Gordin’s one-act plays. Perhaps as a result of my picturesque surroundings, a particular passage jumped out at me: “When an art lover visits a museum, he studies the massive, carefully-executed bronze and marble Rodin statues with no greater interest than he studies the artist’s small plaster figures. Even though they are not fully realized, precisely these works are just as characteristic of Rodin’s talent as his great and more complete works. In this same way, Jacob Gordin’s one-act plays will be endlessly interesting and useful for a researcher or reader.” 1 I have to admit that it had never occurred to me to compare Yiddish dramas with Rodin sculptures. After all, the playwright Gordin famously adapted the work of William Shakespeare, a writer who is known for his completed and full-length works, rather than for sketches or fragmentary studies. Yet Gordin the son’s extended metaphor, almost Homeric in structure, helps demonstrate the importance of his father’s one-act plays.

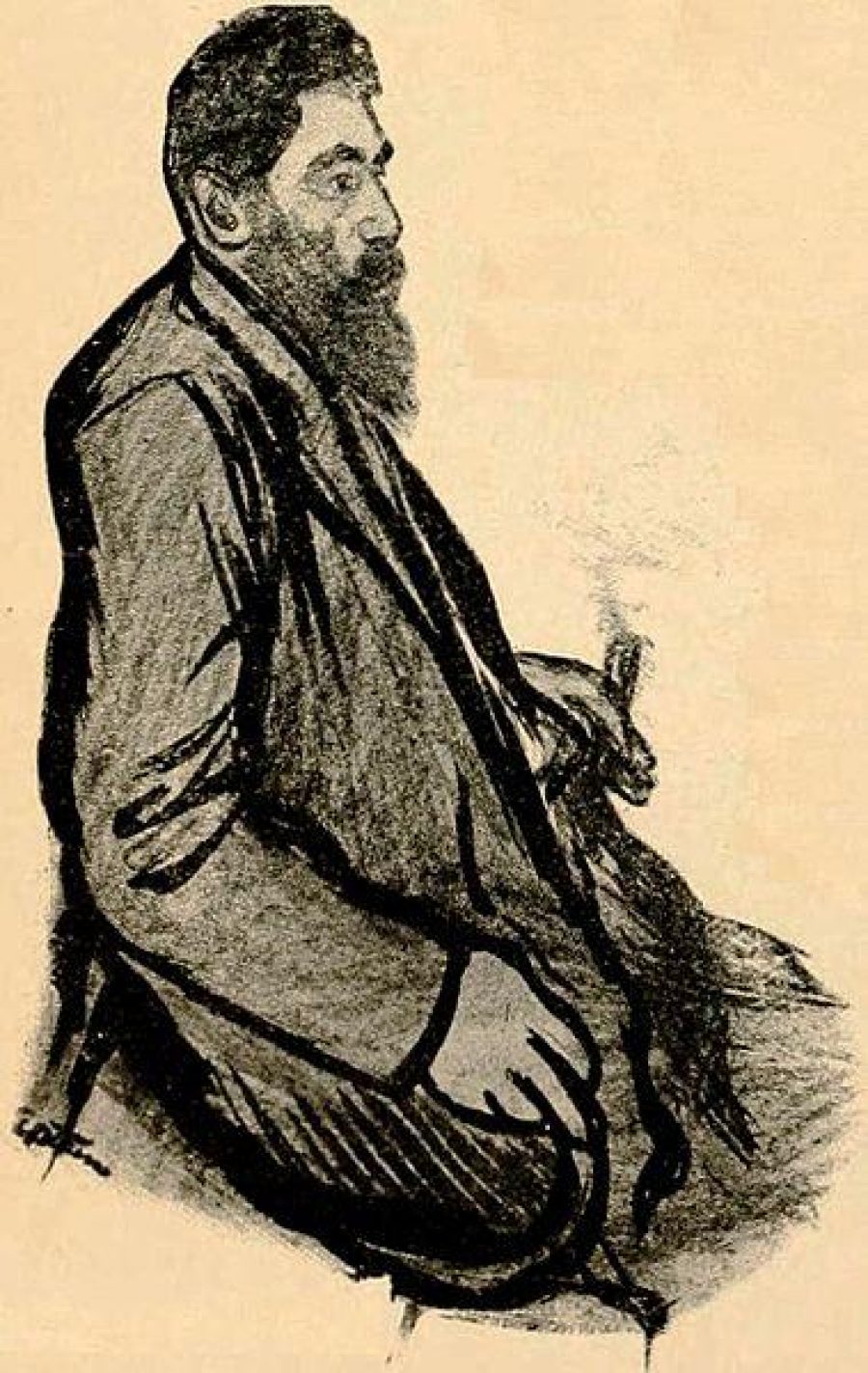

Drawing of Jacob Gordin by Jacob Epstein, from Hutchins Hapgood’s The Spirit of the Ghetto (1902).

Alexander Gordin makes a case for why people should read one-act plays to get a better sense of a playwright’s oeuvre. It made me think about how, for instance, teachers of intermediate Yiddish classes might find it interesting to assign their students one-act plays to read and discuss (PYD could be a useful guide for texts to select). Yet the prologue doesn’t stop here: It argues that one-act plays offer playwrights possibilities and a certain flexibility that might not be available in longer dramatic forms. When the elder Gordin wrote one-act plays, he used them to depict “a momentary thought, a strange occurrence, a funny incident or even an important question of the day” in a more focused way than was possible in a longer work. 2 For instance, the protagonist of his play Farvos mener libn (Why Men Love), criticizes men for not taking women’s opinions seriously, using language that resonates just as much today as it did when it was written. At their best, one-act plays offer spontaneity, freedom from formal dramatic conventions, and the ability to express ideas quickly, sharply, efficiently, and effectively. Alexander Gordin presents the genre as a form of artistic revolt, against both Aristotle’s dramatic unities and the commercialism of the theatre, which could help a playwright engage more directly with important social concerns.

While Gordin’s plays understandably dominate this prologue, they are certainly not the only examples of short Yiddish dramas. One-act plays present a striking variety of themes, character types, and styles, as can be seen in the latest PYD batch, devoted to this genre. Many of these plays explore the social and political issues of their day: Yente Serdatsky depicts radical politics and debates about free love in Oyf der vakh (On Guard) and Israel Ashendorf portrays the emotional weight of surviving the Holocaust in Dos geveyn fun kind (A Child’s Cry) and Bloyz ash (Only Ashes). Other plays deal with more religious themes, such as a Moyshe Nadir puppet play set at the gates of heaven and hell. Sholem Aleichem parodies this concern with the afterlife in his comic burlesque about assimilation, Oylem-habe (The World to Come). Yet for I. L. Peretz in Es brent (It Burns), marriage itself can be hell. Jane Rose takes up a similar idea in her drama Engshaft (Narrowness), which depicts marital conflict in a sweltering New York apartment.

Sketch of Sholem Aleichem by Chaim Topol.

This current batch includes works by classic Yiddish writers, including three plays by Sholem Aleichem, yet such dramas are not necessarily representative of the one-act repertoire. Arguably the one-act play is a particularly democratic form, since it would be easier for even a novice playwright––or one with a demanding day job or family responsibilities––to take a stab at writing a one-act play than a longer dramatic work. It is not so surprisingly that our current batch includes a broad array of playwrights, some of whom are well-known for their dramatic repertoire, and others less so. This variety cannot help but enrich our understanding of the diversity of the Yiddish theatre repertoire. Paula Prilutski delivers a strikingly satirical look at the theatre in her play Aktor (Actor), where characters debate the aims of the acting profession as an actor’s wife groans in childbirth offstage. Would a male playwright necessarily think of putting this kind of labor at the center of a debate about art? It is difficult to say for sure, but we are certainly glad to have a plot synopsis that helps us consider this question.

Yiddish one-act plays are often brief, intense examinations of particular types of relationships or current issues. Their details are often sketchier and the plots more ambiguous than in longer plays, such as illustrated by the fact that several plays refer to protagonists as “the Man” without giving him a name. Yet while Alexander Gordin suggests that a one-act play is comparable to a Rodin study, we’d like to think that an examination of our latest batch (and PYD as a whole) might be more like visiting a Rodin Museum, which impresses visitors with the sheer variety of artistic creation. Indeed, the juxtaposition of plays such as Prilutski’s Aktor and Sholem Asch’s Der zindiker (The Sinner) takes audiences from the cradle to the grave, and invites us to consider how one-act plays depict a range of issues confronting Yiddish-speakers in both the Old Country and the New World. As will be seen—both in this batch and our forthcoming batch (a Part II installment of one-act plays intended for children)—one-act plays offer up a fresh, historically-interesting perspective on the goals of Yiddish playwrights and the topics that interested their audiences.