Chana Pollack called "The Phantom Yiddish Writer," November 20, 2014, https://forward.com/life/209646/the-phantom-yiddis.... Courtesy: Forverts.

Excerpts from In Fayer un Flamen: Togbukh fun a Yidisher Shoyshpilerin (In Fire and Flames: Diary of a Yiddish Actress) by Shoshana Kahan (Part II)

Sheva Zucker, Shoshana Kahan

Read part I here.

Translator’s note: In October 1939, Vilna was given over to Lithuania by the Soviet Union. On August 3, 1940, Lithuania became part of the Soviet Union. On June 22, 1941, Vilna was captured by the Germans and ghettoes were set up. When staying in Vilna began to prove extremely dangerous, the Kahans obtained transit visas through Japan issued by the Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara in Kovno (Kaunas). They travel with a group of refugees on the Trans-Siberian railroad through Soviet territory and then by boat, arriving in Tsuruga, Japan on March 5. There they are met by a delegation from East Jewcom (a committee that concerned itself with the refugees from Poland), who take them to Kobe where they stay until Japan, an axis-power allied with Hitler, refuses to extend their transit visas. They are forced to leave.

Shanghai, a free port, allows them to enter. They arrive in Shanghai on October 23, 1941.

from SHANGHAI

November 6, 1941

Today, the first literary evening arranged by the Yiddish writers took place at the Jewish club. Everyone in Shanghai interested in Yiddish culture came out. Warsaw journalist M[enakhem] Flakser opened the evening and the editor of the local Jewish-Russian weekly newspaper D[avid]. B. Rabinovich spoke. [My husband] Lazar Kahan spoke about the thorny path of the refugees. The critic Y[ehoshua] Rapaport, [the writers B[er] Rosen and [Leyzer] Pines spoke. Raya Zomina sang, and I closed the program with recitations. It was a great success. We spent a lot of time that night at the club with the Jews of Shanghai.

November 20, 1941

Now I’ve played Shanghai. Thank God I got through that evening. The performance took place three days ago and I’m still basking in its success, which was both financial and moral. I came away with 700 Shanghai dollars, a fortune for me now. I lent Rosen 200 dollars right away so he could buy a winter coat, winter is coming.

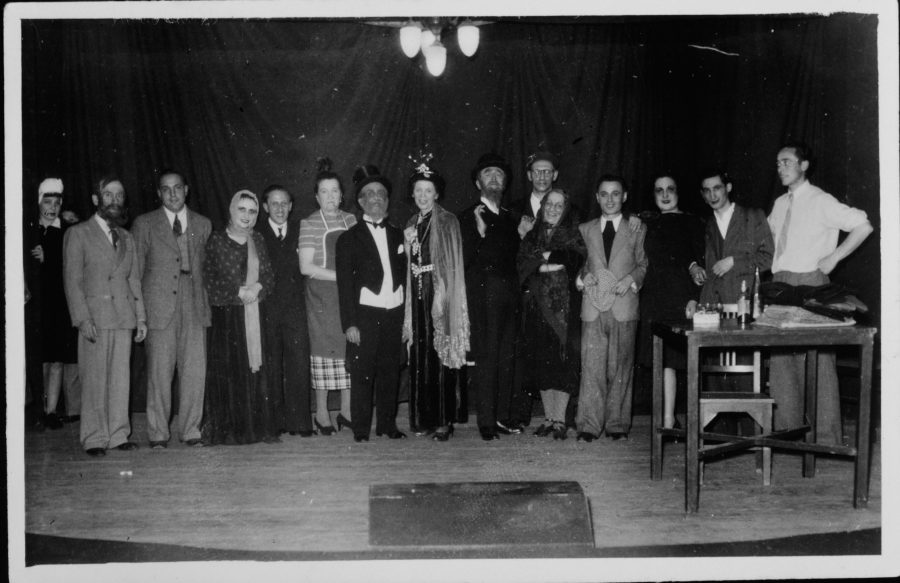

Rose Shoshana Kahan (center) and fellow refugee actors in the cast of Sholem Aleichem’s Yiddish play 200,000, performed in Shanghai on November 21, 1942. Picture published on page 172 of Flight and Rescue, 2001. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Joseph Fiszman

December 20, 1941

Things are bad! Just as we’d predicted. Nothing to be done about it… I had to rent a cheaper room. I took a very small room on Burzho Street. The “fortune” I earned from the concert evening is starting to dwindle… I had overcome all difficulties. We had been well into rehearsals for Dos glik fun morgn (Tomorrow’s Joy), when the new war struck us a terrible blow and nobody was thinking about performing any more… I wander around the streets trying to buy a few containers of jam. After all, one needs to make some preparations. The stores are constantly under siege. You can’t buy anything. Before my eyes I see Warsaw… Will I have the strength to live through this again? There at least I was in my own home and here?… Amidst an Asian people…. And there are murmurs that everything is the fault of the white devils… They are bringing war to the world… The “whites” are quivering. There’s no one that will stick up for us. Shanghai is a lawless city.

Members of a Polish Jewish writers’ group, including Yiddish actress Rose Shoshana Kahan (center, wearing necklace), observe Passover in Kobe, 1941. Picture published on page 124 of Flight and Rescue, 2001. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Joseph Fiszman.

February 20, 1942

Wednesday, the 18th of this month, I played Mirele Efros [by Jacob Gordin]. The performance went off with great success, even though the preparations were so difficult.

February 25, 1942

Today I performed for the Russian-Jewish newspaper Nasha zhizn (Our Life). Recited several pieces. The Russian actors were paid and everyone made a fuss over them. I’m, after all, a “refugee” and a woman, so, well, they don’t need to pay me. I, however, do pay them for running announcements in the paper. Oy, how does one stop being a “refugee”… and be done with “Shamehai”.

March 8, 1942

The work didn’t scare me and today on Purim we were performing again. This time it was a revue. We called today’s show Homen-tashn mit rayz (Homen-tashn with Rice), Shanghai style.

The writer Moyshe Elboym was the emcee and also wrote some numbers; the “sketches” and the song numbers were by [Adam/Avrom] Świsłocki and [Dovid] Markus; music by the famous musician Professor Sheynboym. Lazar Kahan was the literary director. The theatre was sold out. Still it seems like a lot won’t be left over. And I don’t get any support from East Jewcom anymore. According to them, I’m “earning” on my own. I’m happy that we gave the Jews of Shanghai the chance to hear some Yiddish. A lot of the numbers were forbidden by the Japanese authorities. Among them, the main number: “A Trip around the World” by D. Markus.

April 15, 1942

On the evening of the12th we performed the second program. Since it was Peysekh we called the revue Tsvelf kneydlekh (Twelve Matzah Balls). The theatre was sold out.

April 23, 1942

Lazar has become very ill. Yesterday his temperature was forty degrees C. I had to perform at an evening for the Yiddish [perhaps Jewish] school at the Jewish club… It’s very miserable to be alone… But I had to go, although I wanted to hear what Doctor [Yisroel Mordkhe] Shteynman who works with the refugees would say. He’s not just a doctor, he’s a brother to us. He calmed me down. When I got back from the performance, Lazar felt better.

May 10, 1942

Today was the premiere of Tevye der milkhiker (Tevye the Dairyman). I played Golde. I had to stop doing revues, first of all because we couldn’t find any good Yiddish revue performers here, and in Shanghai you can only do each show once because the audience isn’t big enough for two shows. Revues are also very expensive and even a sold-out theatre does not cover the expenses. So we stopped doing variety shows and went back to plays, and specifically to Yiddish plays. But where can they be found?

I sat down, and with the help of my husband, Lazar Kahan, wrote down from memory Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the Dairyman, which I had performed hundreds of times with Morris Lampe in Europe.

I already knew where talented amateurs lived. I had to go to their homes to teach them their roles in Yiddish, create props on my own, direct, act, but I took pleasure in the sold-out houses, because of both the material and artistic success.

June 3, 1942

My first benefit evening. I produced Dos glik fun morgn (Tomorrow’s Joy). It was pouring. The show was very well received. But I lost money on it. Lazar and I had worked on it for a few weeks.

July 10, 1942

For two weeks now I’ve been lying in the hospital on Burzha Street. The performance of [Jacob Gordin’s] Di shkhite (The Slaughter) took place on June the 27th. The theatre was sold out, but I performed with a high fever. The day of the premiere, I collapsed in the middle of rehearsal. I just couldn’t stand on my feet any longer but the performance was a success. We came away with 400 Shanghai dollars. But right after the show, I had to be admitted to the hospital. Dear Dr. Shteynman, the head doctor of the hospital, did everything to get me back on my feet again. But the worms inside of me can’t be gotten rid of. I am too weak and the heat is too great. You can barely breathe.

July 20, 1942

I’m still in the hospital, but I’m feeling a lot better. Today a rumor got out that all the refugees will be sent to a concentration camp.

Translator’s note: Although it was more than just a rumor (leading Nazis were sent to Shanghai to discuss this plan with the Japanese occupiers in power), the plan, fortunately, never materialized.

January 27, 1943

The censor struck the one-act play Mentshn (Servants) by Sholem-Aleichem from the program. Because… Because…. it isn’t moral. It was the Yiddish censor that did it. Lazar went to the censorship office with a German translation but it didn’t help.

February 18, 1943

The thing that we feared has finally come to pass. Today an official announcement was issued that everyone who arrived after 1937 must move to a specially appointed area. They’ve given it a genteel name, “Designated living area.” They’re ashamed to call it by its real name – ghetto. So this means that we’re being imprisoned in a ghetto. Is this why we had to flee thousands of miles? To be imprisoned in a ghetto?

Translator’s note: In this next entry, Shoshana mentions a “farewell evening.” She never explains the reason for this “farewell evening” but it seems that it is because she will be going into the ghetto. The Shanghai Ghetto, formally known as the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees, was an area of approximately one square mile in the Hongkew district of Japanese-occupied Shanghai. It was one of the poorest and most crowded areas of the city. About 23,000 of the city’s Jewish refugees were restricted or relocated to the area from 1941 to 1945. Local Jewish families and American Jewish charities aided them with shelter, food, and clothing. Although the Japanese authorities increasingly stepped up restrictions, the ghetto was not walled. However, a pass was required to leave and reenter, and arriving after curfew could cause ghetto residents to be put in jail. There, it was not uncommon for prisoners to contract typhus and die.

May 2, 1943

Today, my farewell evening took place. I staged Dem umbakanter (The Stranger) by Jacob Gordin.

The mood was heavy. Everyone knew that in sixteen days from now, we would have to go live in a ghetto. It was a holiday, and at the same time it was a day of mourning. The committee arranged everything very nicely… After the performance, a banquet took place in the club restaurant. So I’m bidding farewell to Yiddish theatre in Shanghai…

November 11, 1944

The alarm today lasted four hours. The explosions were terrible. The houses were shaking and in Hongkew [the area where the Jewish ghetto was located] the Chinese were in a panic. People were running back and forth afraid of the flying bombs. Naturally, I couldn’t go into the city today and the performance is three days from now. All day long, wounded people were being carried off. The Japanese airport and an ammunition factory were bombed.

November 21, 1944

A terrible day and a terrible night. The alarms and the bombings last all night and all day. They bombed Nanda and the Japanese section called Yangshupu [in the district of Yangpu]. Wagons and carloads full of the wounded pass through [Hongkew]. The hospitals are full of wounded Chinese people. I was lucky, it seems the airplanes had made an agreement with me not to come near me.

The theatre was full. I succeeded both morally and financially, and I’ll have something to live on for quite some time. I performed in Sholem Aleichem’s Konkurentn (Competitors) and recited [Shimen] Frug, Mani Leyb and some Sholem Aleichem monologues. The famous Russian actor Soveleyev took part, as well as [Srul] Vinogradov and [Yosl] Mlotek; Soveleyev was the emcee. The mood among the audience was elevated; there hadn’t been a Yiddish event for a long time and this gave people an opportunity to get together. When people started to leave, there was an alarm. Many hadn’t managed to leave before the alarm, so they stayed at the club. Others hid between the buildings and were, of course, upset that they had left the house at such a time. I stayed at the club too. But it was worse for me. My pass was only good until 11. I had been certain that I would ride home from the show in a pedicab (a kind of bicycle combined with a rickshaw - the coolie rides on the bicycle instead of pulling the rickshaw while running). We had finished early, just after 9, but the alarm lasted two full hours, so I had to leave for home after 11. With a pounding heart I sat in the pedicab. When I saw a Japanese person, I trembled. When I finally caught sight of the ghetto border I was very relieved. On the way home, heavy bombing started again, and it went on like that all night and all day. One bomb hit the power station, and we’re sitting here completely in the dark.

July 1, 1945

I performed again in the ghetto. In the Kadoorie School. It was a memorial evening for [the Hebrew/Yiddish poet] Khaim-Nakhmen] Bialik and [Theodor] Herzl. It took place in the garden. For the first time I recited using a microphone. More than a thousand people were there. I recited Bialik’s “Letste vort” (Last Word) and [the Yiddish poet] Morris Rosenfeld’s “Afn buzem fun yam” (On the Bosom of the Sea) (slightly modernized). Tonight nobody in the ghetto slept; The stifling heat was terrible and the bombing even more terrible.

In Hongkew, people are walking around rejoicing. The ghetto is being opened. We still will not be allowed to move into the city, but we will be able to move about freely. What came out of all this talk – even greater restrictions…

December 2, 1945

Today, the Jewish Welfare Board organized a Hanukkah evening for the poor refugees of Alcock Home. I recited Morris Rosenfeld’s “Khanike-likhtlekh” (Hanukkah Candles), Bialik’s “A Freylekhs” (A Happy Song) and a humorous number about the barmaids that I wrote myself. I got ten dollars and I’m really happy.

January 13, 1946

In the evening, I ran off to perform recitations in the Eastern Theatre at the evening organized by the Jewish American Welfare Board. The German Jews have taken a liking to Yiddish, or maybe they are moved by the timely recitations.

Purim, March 17, 1946

As with all holidays and Shabosim, we had a good meal at the Tukaczynskis. But I had to hurry, because I had to go back to the ghetto to participate in the Purim celebration organized by the Jewish Welfare Board at the Eastern Theatre. My recitation was the only number that had anything to do with Purim… After the recitation, a Jewish chaplain, Major Marcus Brenner, came backstage. He was so moved by [hearing ] the Yiddish language on stage that he didn’t know how to thank me. He had flown to Shanghai from the island of Okinawa to provide the Jewish soldiers of Okinawa with kosher meat for Peysekh. He speaks Yiddish so fluently, this major, that I couldn’t believe that he was actually an American military man. After that I went to perform at an evening at the “Atomic” auditorium arranged by the Revisionists. Again, I was the only Purim number on the program, and the only one performing in Yiddish. Here you can hear all languages, Russian, English, but not Yiddish.

April 2, 1946

Got a lot of letters, but among them the letter of letters, the contract I had so dreamed of. Reuven Guskin [head of the Hebrew Actors’ Union in New York] sent me a contract signed by [the actress] Jennie Goldstein and her husband Charles Grohl. I cried and caressed the piece of paper. Jennie Goldstein never laid eyes on me, nor I on her, and yet she did so much for a stranger, someone she didn’t even know because Mr. Guskin asked her to. Lazar is walking around beaming… Despite the hot weather today, he ran to the emigration office and then to Mr. Honik to consult with him; after all, he’s some kind of a lawyer. Then to the representative of the “Joint” [Distribution Committee], Mr. Jordan, and arranged to go with him to the American consul. All day long people we know came by to congratulate us, although it’s still quite far from a proper congratulations, but the door has been opened… I didn’t go do any trading… I don’t need it now… There is a bit of money from the actors’ union. There are packages from “UNRA.” We already bought a big trunk… What more do we need? We’re happy!

Translator’s note: Soon after the good news, both Shoshana and her husband contracted typhus and were in the Jewish hospital for refugees. In order not to upset her, the seriousness of Lazar’s condition was kept from her.

from IN THE REFUGEE HOSPITAL

July 12, 1946

A black page. A sad page. Lazar is no longer here. My husband is no longer here. I wasn’t even at his funeral, I was not even at his sickbed. He died alone, abandoned… Lonely as a stone. Neither his wife nor his children accompanied him to his eternal rest, nor did they hear his last request. He died without a warm word of comfort, poor Lazar.

… It was Friday evening. In the hospital candles were being lit in honor of the Sabbath. Women from the “women’s association” come to bring a bit of fruit for the sick people and to light candles… That Friday evening, summoning up his last bit of strength, Lazar struggled. That was May the 24th and during the day of the 26th this gentle good soul breathed his last.

October 14, 1946

I have my visa! An American visa, I’ll be able to leave. … I’ll be leaving in a few days. I have to be in New York before November 1st. That was the condition under which I got the visa.

When I returned from the consul, I took flowers to Lazar’s grave. Only now do I feel that poor Lazar will remain abandoned on foreign soil, far from loved ones and with no one to visit his grave. Now at least I go every day to cry my heart out on this mute grave… The big beautiful tombstone is my consolation and I have the writers’ group to thank for this, because they did everything possible to see to it that Lazar would have a tombstone before I left.

October 22, 1946

This morning we didn’t leave either [because of a typhoon on Oct. 20]. It’ll be evening before we leave. Not leaving on Saturday because of the typhoon turned out to be a good thing. Saturday morning, the 21st, the Italian consul let me know that there was an Italian visa waiting for me. I ran to get the visa, although I’m not going to go to Italy now.

Everyone that came to accompany me in the morning had to go back. But I didn’t go into the city anymore. I stayed and waited until evening when the airplane finally took off. And so I said goodbye to Shanghai… 5 bitter years… and my husband, left behind at the cemetery.