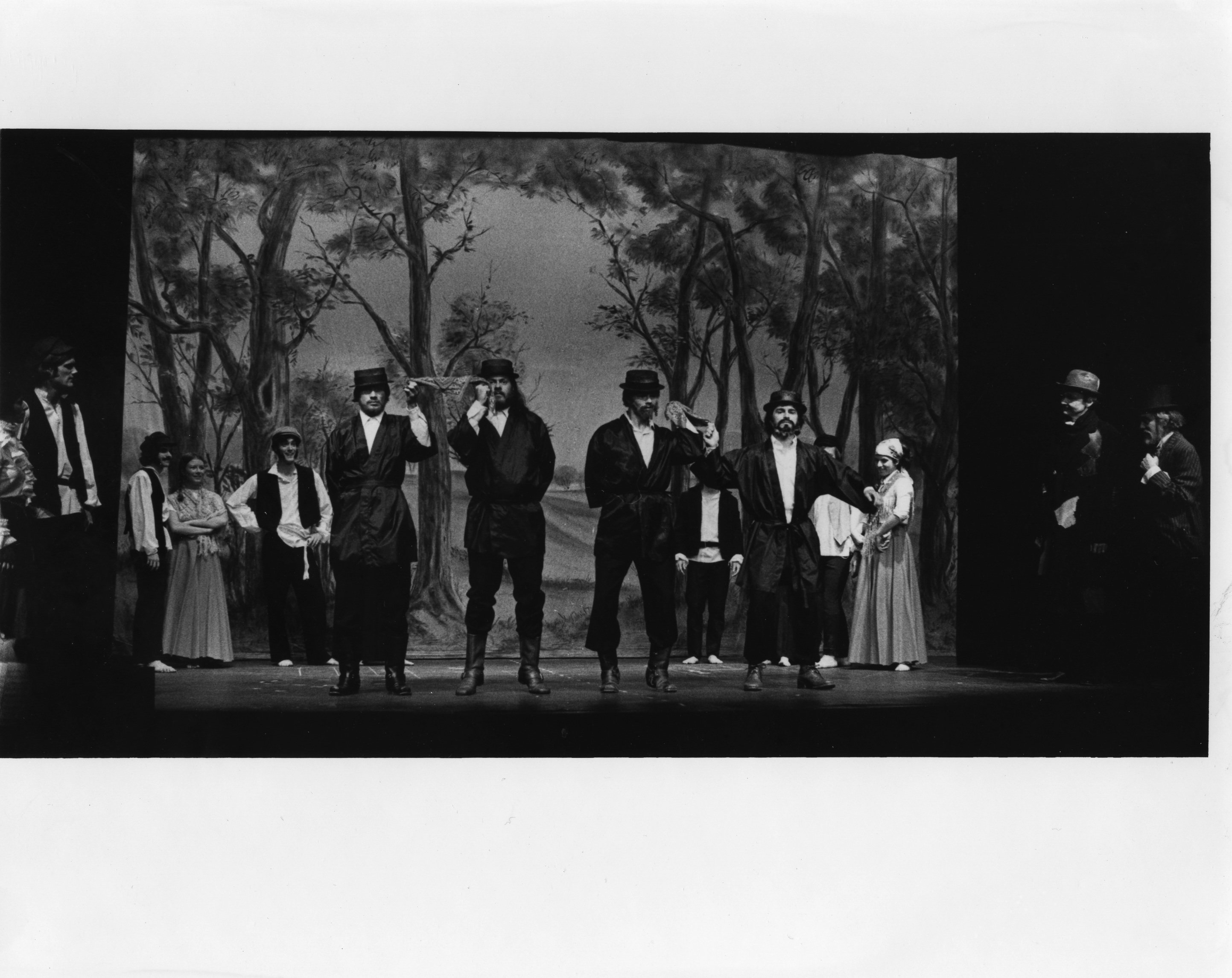

Dance Sequence in Joseph Lateiner’s Dovids fidele, Wesleyan University, 1976. Photographer: Carol Reck.

Revival and Homage Productions of Yiddish Theatre

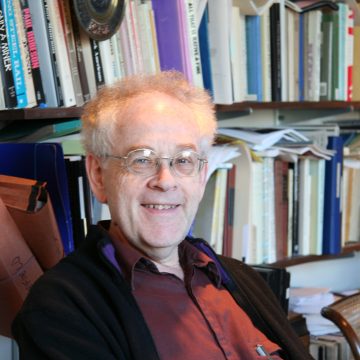

Mark Slobin

Since the 1970s, Yiddish theatre has been brought back to audiences in several ways, and the number of productions keeps increasing. There’s something about the popular entertainment of the 1880s-1930s that draws people to fool around with creative ways of making it contemporary. I’ve done my own experimentation, so have some sense of the possibilities and pitfalls. There are two main types of reconstruction: Revival and Homage.

The recent Di goldene kale (The Golden Bride) production at the Folksbiene took Michael Ochs years to construct, from research to grant writing. It offered the first full-scale revival of a classic operetta by the top dog of the genre, Joseph Rumshinsky. Looking more closely, Ochs and his creative partner Zalman Mlotek had to make a lot of choices. Yiddish theatre was never standardized, so you have to pick your way through variant scripts, make orchestration choices, and adjust to the aesthetic of our day. It’s like doing early music.

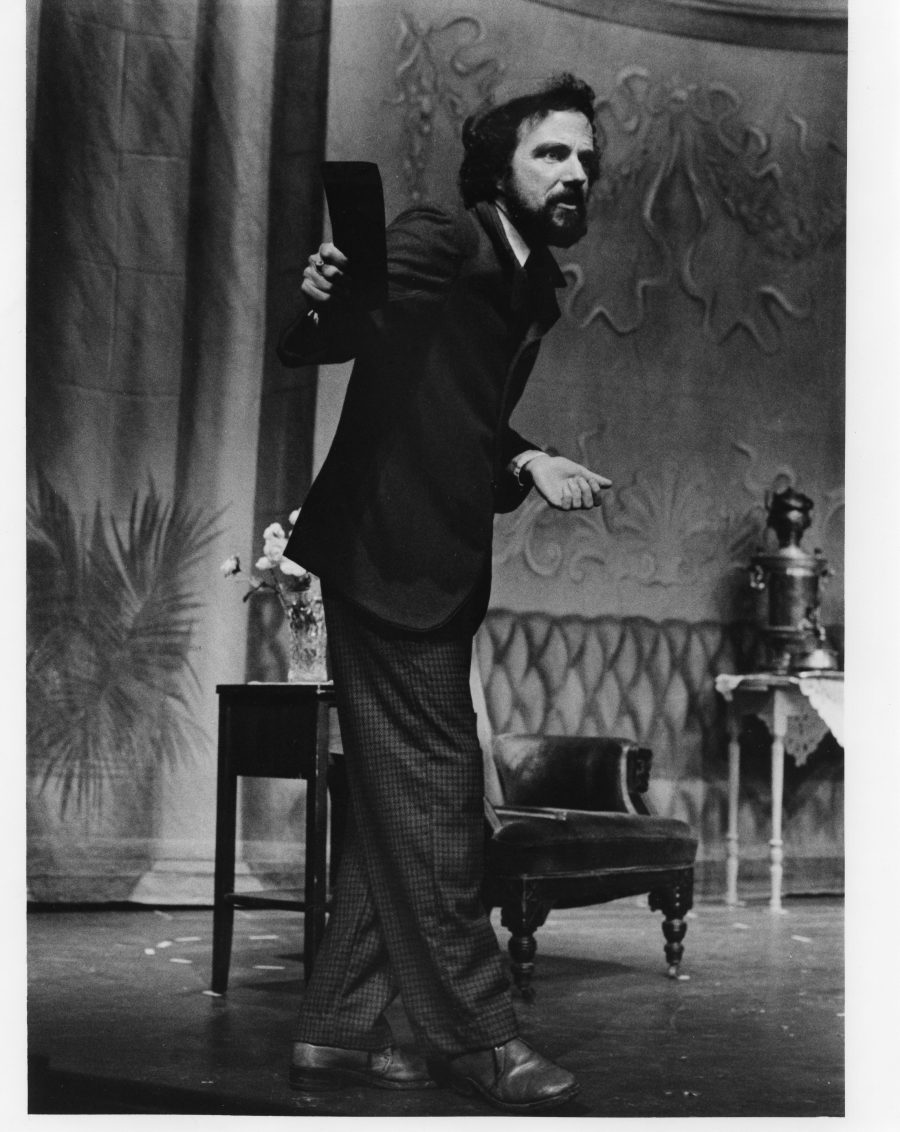

Andy Szegedy-Maszak as Solomon in Joseph Lateiner’s Dovids fidele, Wesleyan University, 1976. Photographer: Carol Reck.

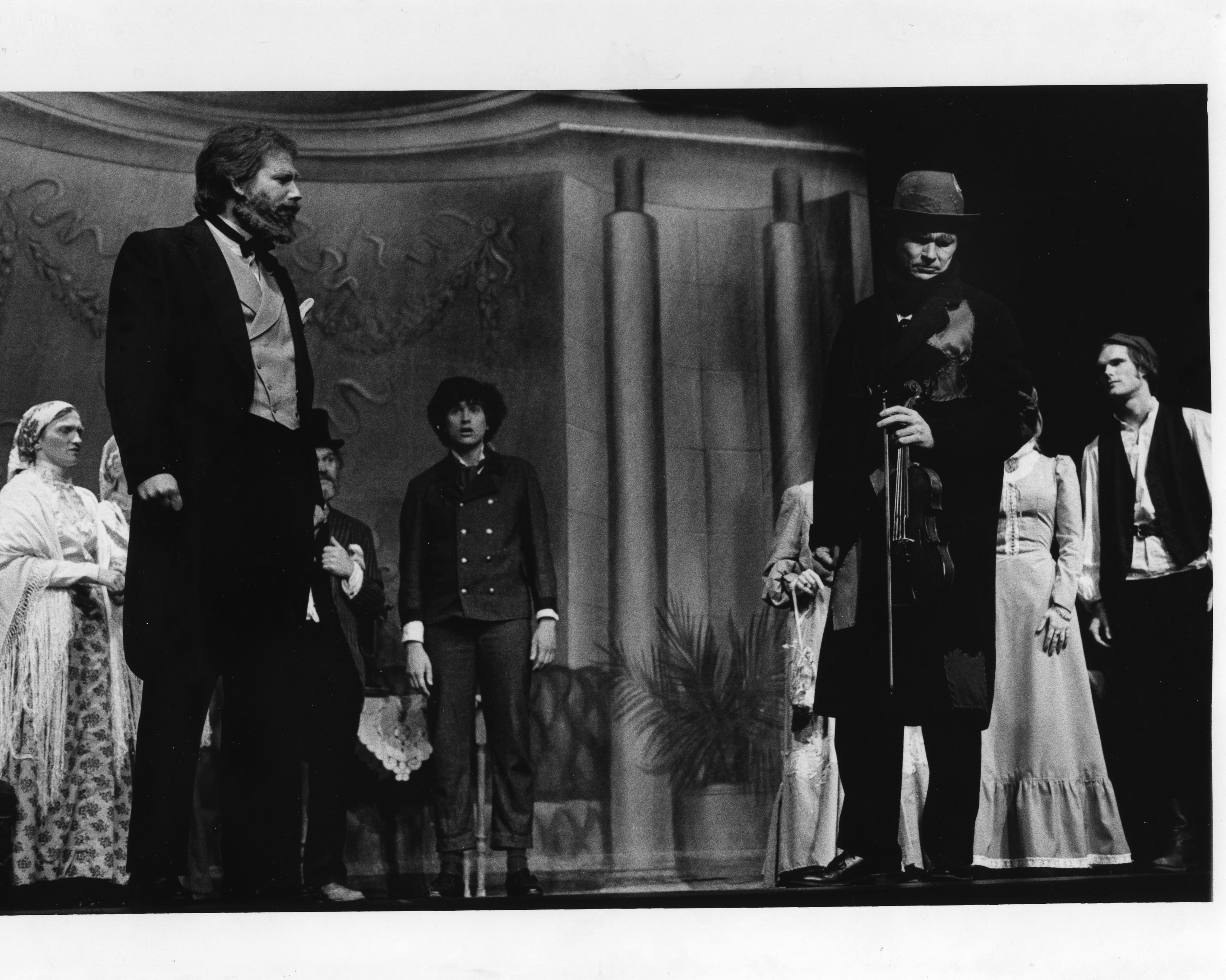

I faced those challenges back in 1976, when I produced a full-length performing version of Lateiner’s Dovids fidele, oder der tsoyberkraft fun muzik (David’s Violin, or The Magic Power of Music) written thirty years before Di goldene kale. 1 It was even murkier in its sources, including what its musical content might actually have been on a given night in 1897, from Cleveland to Cape Town, the homes for just a couple of the scripts that I found in the YIVO archives. The versions didn’t even agree on the dramatis personae, let alone the music. So, like all restoration of heritage, as Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett pointed out long ago, “revival” is actually reconstruction. To simulate the popular culture reception of Yiddish melodrama, I did the play in English, with a local campus cast of faculty and students that the audience could identify with.

I also experimented with vaudeville, using our only surviving Yiddish playlet, Tsvishn indianer (Among the Indians) of 1895, by K. Y. Minikes.

2

This question of staging a piece that was innocuous at the time, but seems off-limits to today’s audience, extends to a huge swath of the American repertoire. In the case of an in-house genre like Yiddish-language entertainment, the issue looks different than it does for mainstream products, e.g. blackface in Hollywood film. In its day (and it probably was only one day at the Windsor Theatre), Among the Indians demonstrated mastery of American popular culture, perhaps even educating its audience into those stereotypes, as part of a long process of acculturation. Whether nowadays one wants to just read it on the page, in translation, or consider staging the playlet involves a different set of concerns.

Glenn Young as Tevya, Richard Vann as David in Joseph Lateiner’s Dovids fidele, Wesleyan University, 1976. Photographer: Carol Reck.

“The Four Hasidim” number in Joseph Lateiner’s Dovids fidele, Wesleyan University, 1976. Photographer: Carol Reck.

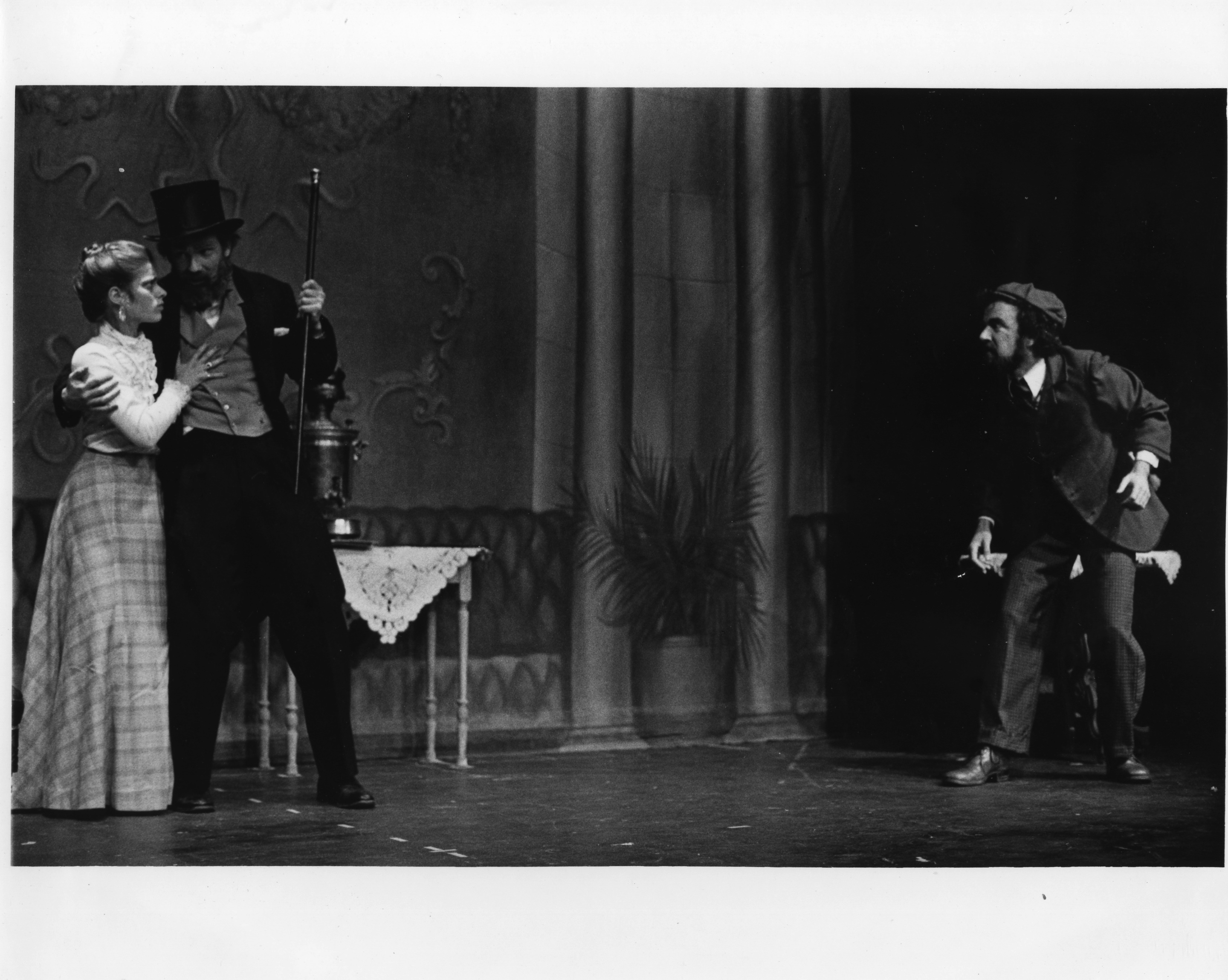

Glenn Young as Tevya, Juliet Green as Eve, Andy Szegedy-Maszak as Solomon in Joseph Lateiner’s Dovids fidele, Wesleyan University, 1976. Photographer: Carol Reck.

This category might include Tony Kushner’s adaptation of The Dybbuk, ostensibly a revival, but with a few alterations that shifted the play’s meaning, especially a moment of Holocaust forecast. The Klezmatics’ accomplished score paid tribute to the original music we associate with the play while adding its own creative take on tradition.

Paula Vogel’s Indecent has brought to Broadway itself a more advanced version of homage to a Yiddish classic, in this case Sholem Asch’s play Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance). Asch and his collaborators become full-scale characters while the play is backgrounded to serve as a plot device for covering a long chronology of productions and their consequences. The fine score by Lisa Gutkin and Aaron Halva helps ground a period sense and keeps alive the necessary importance of music in Yiddish theater, and the show has been well received, partly due to the current interest in same-sex content and moral censorship.

I paid my own homage to the early Yiddish theatre in a one-act musical called Mogulesco: A Tale of the Yiddish Theater, which premiered at Wesleyan University in 2011, though it was written decades earlier. I had received a grant from the NEA to do a performing version in English of Goldfaden’s classic Shulamis, but found the play so unwieldy and intractable (pace Zalmen Mlotek, who eventually did produce a modern version) that I gave the project up, instead creating my own tribute to that neglected hero of the early Yiddish stage and music, Zigmund/Zelig Mogulesco, Goldfaden’s main early collaborator. The frame is a staging of the interview that Abraham Cahan of the Forverts did with Mogulesco in his last years. As they talk about the past, the scene switches to the actor/composer’s memories of how he worked with Goldfaden on Shmendrik and Shulamis, with some newly-composed interpolations Mogulesco claims to have written. There is a substitute opening march of pilgrims—really clunky in Goldfaden’s version—written by my late friend, the composer Louis Weingarden. He also penned a fine aria for Shulamis, when she’s lost in the desert. Standard items I included are from the bride-swapping scene in Shmendrik and “Rozhinkes mit mandlen” and the maiden’s dance from Shulamis.

In my vision, Mogulesco, the fleet, funny, sardonic “Charlie Chaplin of the Yiddish stage,” sees Goldfaden as a pompous Haskalah nostalgic nationalist. As a closer, Chaplin himself appears: Mogulesco takes posthumous credit for the hilarious 1923 Gus Goldstein recorded routine “Tsar nikolay un tsharli tshaplin” (Czar Nicholas and Charlie Chaplin). My set-up has Cahan being called to the office, because the Russian Revolution has broken out. Mogulesco, ostensibly expired, jumps up and exclaims “I had just the number for this moment.” In the skit, the Czar arrives penniless in New York and begs a crowd of Jews for a job. They won’t let him be a garment worker because he was a boss, can’t have a pushcart, only for Galitsianers, and he can’t run a deli because that’s only for Romanians. Chaplin appears and offers him a job in the movies as a straight man. In my version, the two duel with a pair of salamis. Watching the fracas, Cahan says “Mogulesco, where are you now that we need you.” 3

There must be many more ways to build contemporary shows out of the treasure-house of the old Yiddish theatre. I’m not sure about literal revival, onstage currently at the Folksbiene in the tryouts for a new production of Goldfaden’s 1878 Di Kishefmakherin (The Sorceress), though it’s always great to see the classics live. I look forward to seeing the drama world come up with the kind of imagination and energy that is now coming into Yiddish instrumental and vocal music among younger artists, a surprising surge not evident ten or fifteen years ago. The success of Di goldene kale and Indecent shows that with enough contextualization, today’s audience can be drawn into what might seem like antiquated storylines, as long as the music is effective, the action is non-stop, the production level is high, and the acting and direction are imaginative.

Notes

-

1The script and musical sources for David’s Violin, as well as for a scene from Lateiner’s Shloyme gorgl appear in Mark Slobin, ed., Nineteenth-Century American Musical Theater, Volume 11: Yiddish Theater in America (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1994).

-

2My annotated translation appeared in The Drama Review 24, no. 3, 1980, 17-26 and was reprinted in J. Schechter, ed. Popular Theatre: A Sourcebook (London: Routledge, 2003), 202-211.

-

3A performing edition, including instrumental parts, is available on PDF to any interested parties. The show was also produced at Tufts University in 2012, the same year I presented on it at the International Yiddish Theater Festival in Montreal.