Opening scene. Photo by Nicola Hearn. From left: Andryusha Kuznetsov as Leybl, Kostya Shapiro-Tchourine as Azarye.

Vos flist durkhn oder: A conversation with playwright Mikhl Yashinsky on his new play

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

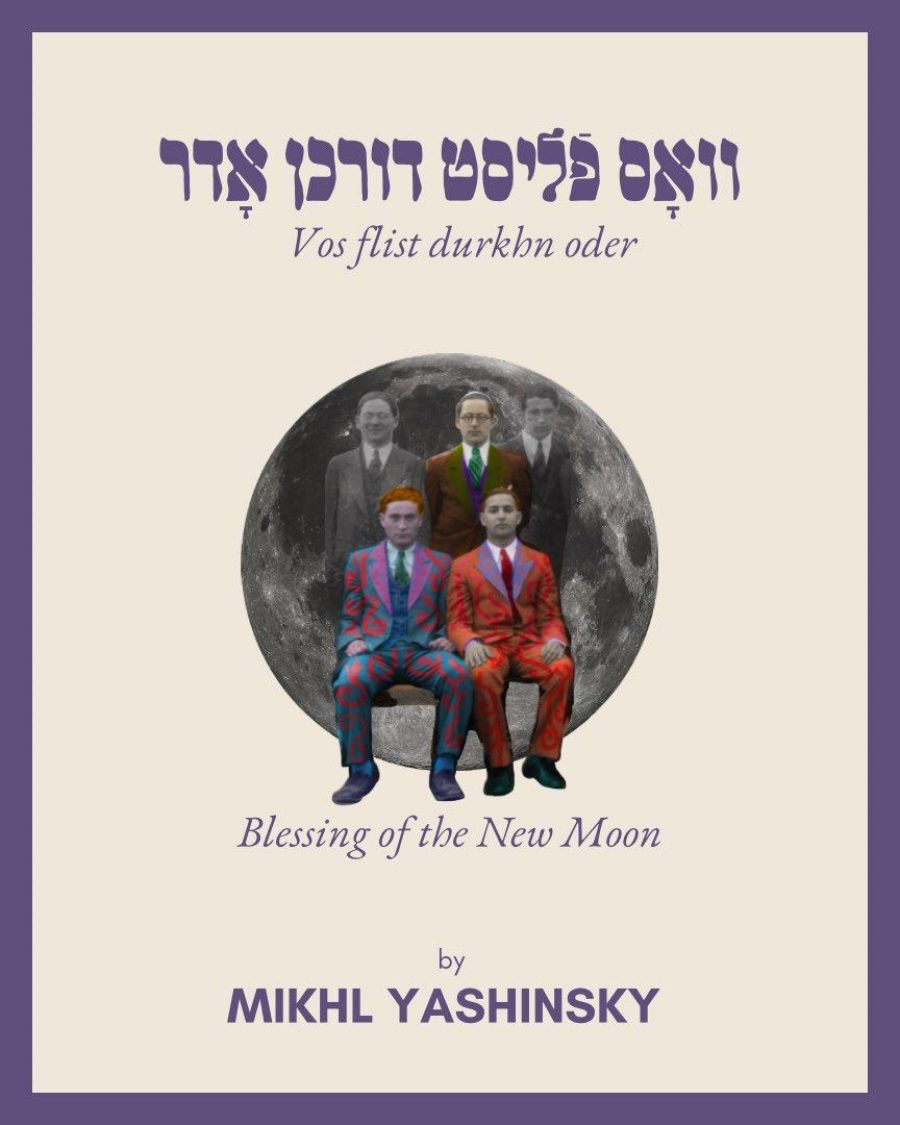

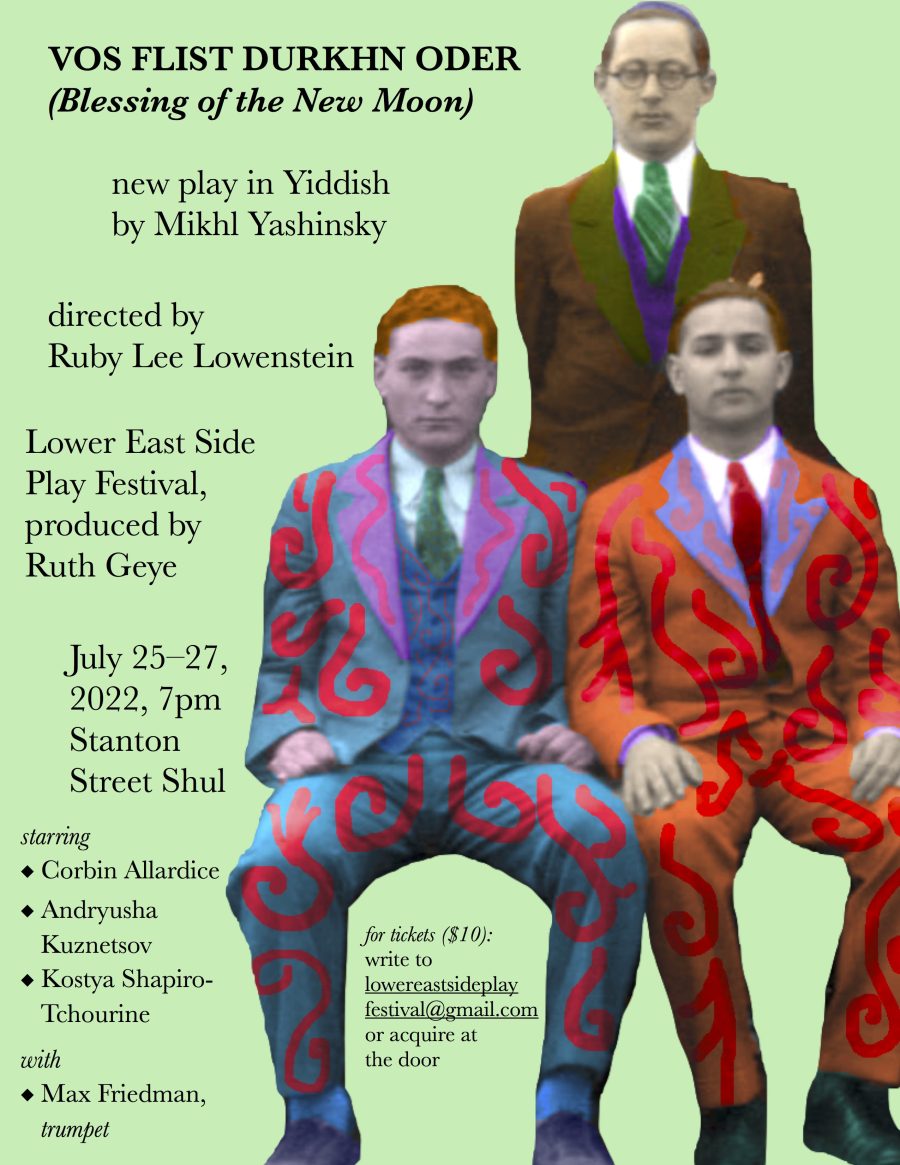

Mikhl Yashinsky’s new one-act Yiddish play, Vos flist durkhn oder (Blessing of the New Moon), premiered at the Lower East Side Play Festival, produced by Ruth Geye and presented at the Stanton Street Shul in New York City on July 25, 2022, with encore performances on July 26 and 27. The play was directed by Ruby Lee Lowenstein, and starred Andryusha Kuznetsov as Leybl, Kostya Shapiro-Tchourine as Azarye, and Corbin Allardice as Shayke. English supertitles were provided, and Max Friedman contributed live incidental music on his trumpet.

Vos flist durkhn oder was one of six short plays chosen out of more than 150 submissions to the festival, and the only one not in English. The festival presented these works—ranging from the comic to the poignant—in the same evening(s) at a historical tenement synagogue, a setting that emphasized intimate character interactions in a local context. This setting also allowed the audience to experience Vos flist durkhn oder within the general context of local theatre, rather than being limited to the realm of Yiddish or Jewish theatre.

The play is set in 1912 in the then newly-built yeshiva Mesivta Tiferes Yerusholayim (still active today as Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem) on New York’s Lower East Side, on the eve of the new moon for the Jewish month of Adar. Yeshiva students Leybl and Azarye want to celebrate a folkloric tradition observed on Rosh Khoydesh Oder, the new moon preceding the month of Purim. Their classmate and friend Shayke seems a perfect candidate to celebrate with them, but can they convince him to participate? What happens when the fiery emotions of fear and passion collide?

Yashinsky’s play incorporates traditional and modern elements. The yeshiva setting is traditional and insular, while the New York City location lets the characters reference nontraditional expressions of sexuality, gender, and belief (or lack thereof) in a secular American environment. One could even argue that the palpable homoeroticism of the play is traditional, as befits a yeshiva or any ostensibly single-gender environment where young hormones and curious minds abound. But the play doesn’t simply hint at homoeroticism; it allows us to see a world, both historically and in the present, where people dare to express their desires.

The natural cadences of the play’s Yiddish dialogue are informed by the playwright’s Yiddish and Hebrew studies, and by the Yiddish-speaking cast, who along with their linguistic abilities bring a natural charisma and distinctive personalities to the stage. Leybl’s gaze is playful yet piercing. Azarye is milder and sweeter, with a wiry energy. Shayke is endearingly hapless, until his fanaticism threatens the others.

The playwright, Mikhl Yashinsky, is a familiar figure on the Yiddish street as a self-described Yiddishist and theatrist—he’s an actor, playwright, and stage director. A descendant of actors, he attended Jewish religious school for twelve years, and has studied and worked with Yiddish intensively at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and the Yiddish Book Center, where he co-authored the textbook In eynem. He is also a frequent teacher of Yiddish language, and teaches mornings in YIVO’s summer program, after which he heads to rehearsal rooms to prepare this production.

Recently, I sat down with Mikhl to discuss the play.

Vos Flist Durkhn Oder. Flier Image By Mikhl Yashinsky and Ruth Geye.

M-KhS: I was struck by the title of your play, Vos flist durkhn oder, because when hearing it or reading it in transliteration, there are three possible meanings for oder: the Jewish month of Adar [pronounced oder in Yiddish], the word “vein” and even the river Oder, which flows through Central and Eastern Europe. [The play title is spelled in Yiddish using the month of Adar]. How did you choose the title?

M-Y: I chose the title thinking of the desires that course through a person’s veins, and also through the month of Adar, thinking of what drives people, the latent passions in the blood. There is a recklessness and frivolity traditionally associated with the month of Adar, when Purim takes place, a letting loose and giving in to the human need for joy, feasting, music, wildness.

M-KhS: What sparked your inspiration to write this play?

M-Y: I had the idea several years ago to write it. I spent three years at the Yiddish Book Center, a building full of books and the ideas that are contained within them and call out for release. It was a fruitful environment for me that allowed my Yiddish and creativity to ferment, and I got so many ideas there. Once I was in the so-called “book vault” leafing through Max Weinreich’s Geshikhte fun der yidisher shprakh (History of the Yiddish Language), specifically the chapter on the way of the Shas, where he writes about language and phraseology ultimately originating in Talmudic discourse and religious practice. There I came across the curious phrase “makhn a mishenikhnes.”

“Makhn a mishenikhnes hot bay yeshive-bokhirim geheysn a shtiferay rosh-khoydesh-oder, ven khevre hobn gekhapt a bokher, im ‘arayngetsimblt’ un derbay gezungen ‘mishenikhnes oder marbin besimkhe’.”

In English, “In the language of yeshiva boys, ‘making a mishenikhnes’ signified a bit of mischief on the New Moon of Adar, when a gang of them would seize a fellow student and ‘let him have it,’ all while singing the traditional song, ‘Mishenikhnes oder marbin besimkhe’—‘When the month of Adar arrives, our ecstasy increases.’”)

I thought it was so unusual. Weinreich doesn’t elaborate. I started thinking and imagining what might have inspired such a ritual, what might be behind it, in the minds and bodies of those taking part. I wrote down the quotation. It was around Purim. I posted the quotation on Facebook six years ago, and appreciated friends’ surprise when they learned of the custom along with me—it’s nice to have this finally emerge after all that time!

Flier for Vos flist durkhn oder. Designed By Mikhl Yashinsky, using a photo of NYC Yeshiva grads from the 1920s.

M-KhS: How did you create the characters?

M-Y: Names are important to me, and are sometimes the beginning of how I visualize a character. I have a Haredi uncle who became very frum as a teenager and made aliyah, and he has several children who attended yeshiva. One of these cousins is named Shayke, and he has an intriguing personality. The yeshiva life as I’ve understood it provided some inspiration as to how my characters behave and talk, with their loquacity and their explaining and arguing and language rich with loshn-koydesh, Hebrew and Aramaic words from their poring over the holy texts. The character Shayke is a shlimazl—he is not as charismatic as the others. He’s immersed in his studies. But Adar is about coming out of oneself, and tension emerges between the characters. A lot happens with the arrival of a new moon! I am not sure there are many Rosh Chodesh plays in the Yiddish theatrical repertoire—I am pleased to have added one. The name Leybl comes from another uncle who was called that by my grandmother, and means “lion,” I think encapsulating some of that character’s bravado. When I chose the name Azarye, I was thinking of a rabbinics teacher by that name who I had in high school and who taught us Talmud. He was a scholar, but only just out of yeshiva himself, with stores of youth and charm. And the name’s meaning, “God has helped,” also plays into a supernatural motif woven through the play that receives its apotheosis in the final moments.

M-KhS: How was it to write the play in Yiddish? Did your Yiddish change or grow in the years between when you first wrote down the idea and when you wrote the play?

M-Y: Certainly, since I first wrote down the idea, I’ve grown, read, written, translated, taught, and immersed myself, and becoming far more comfortable in the language. Oscar Wilde wrote Salome in French, even though he was a native English speaker. Why? I was amazed when I learned that as a youth, and then read the play—I couldn’t believe how good it was, it being a second language for him. But now I’ve done it myself. Lehavdl, I am not putting myself on his level of artistry, but my endeavors in this realm were perhaps inspired partly by his example. Still, I’m not writing in Yiddish just to achieve something. It’s what I feel like writing, it’s what makes sense, it’s the natural idiom for this story and these characters. Last summer, I wrote a full-length play in Yiddish. Writing that gave me the feeling that I could do it. This short play does feel complete unto itself.

Performance photo by Jeremy Walsh. From left: Andryusha Kuznetsov as Leybl, Corbin Allardice as Shayke, Kostya Shapiro-Tchourine as Azarye.

M-KhS: How did this all come together?

M-Y: This festival presented an opportunity to write the play, which I had jotted down ideas for in my notebook of miscellanies and put away for several years. The Lower East Side Play Festival called for plays set on the Lower East Side, and welcomed plays in languages other than English, owing to the linguistic diversity of the Lower East Side. Of the more than 150 submissions, six plays were chosen, mine the only one not in English, but all demonstrating a diversity of attitude and culture. Interestingly, the festival did not ask me to translate the play—they already had a few Yiddish readers on their panel. When I wrote the play, I thought, why couldn’t the yeshiva be on the Lower East Side? I chose the Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, which is today the only active yeshiva in the neighborhood, the only one extant from the heyday of Eastern European-Jewish life and activity on the Lower East.

Curtain Call. Photo by Uri Schreter. Front row, from left: Director Ruby Lee Lowenstein, Playwright Mikhl Yashinsky.

M-KhS: What has emerged in your work with the director and actors to prepare the play for its stage debut?

M-Y: Ruby Lowenstein, our insightful director, wanted our wonderful actors to feel the shifts of power in the text. All of the characters have powerful and powerless moments. When we did Ruby’s warm-up asking us to describe times when we have felt powerful or powerless or both, I talked of teaching Yiddish. In the classroom, I am ostensibly in charge, but the students are also powerful; their conduct, their response to what I present, define the mood of the class. At the beginning of the play, the characters are sweating and hot; the emotions are hot. At the end, they have given themselves up; the characters are allowing themselves to be, even as outside forces are closing in. The character Leybl says he will have smikhe (rabbinic ordination) next year. Why does he bring it up in the midst of their ritual? Because of the delicious incongruity—he’s to be a rabbi next year, and here he is slapping another boy and singing. But he’s having fun; there is a mixture of fear and excitement. Transgression is scary and dangerous, but there is a pleasure element to it—and as one of my idols Nigella Lawson says, there is no such thing as a “guilty pleasure,” as the one thing you shouldn’t feel guilty about is having pleasure. The boys’ custom is traditional and festive, but to others, it seems out of bounds and frighteningly untraditional, and I’m trying to explore that confluence.

Mikhl Yashinsky with students after the play, outside the shul.

M-KhS: I think that many of us in the LGBTQ+ community have the sense that sometimes we have to write ourselves into history. Did you think about this when writing the play?

M-Y: When writing about getting into a group and spanking someone, the [historical texts] don’t talk about what’s behind that. I found a couple of descriptions in memoirs, a clear delineation of the steps of the ritual, but not of the emotions behind it. One memoir refers to “the one who enters” (a play on the word “mishenikhnes,” sung in the traditional tune that accompanies the ritual), and when he comes in to the beis-midrash, the other boys drag him onto the shulkhan, the table where the Torah is read. The person who got spanked got it with such intensity that he would have trouble walking afterwards. But it’s not only violent; it’s a shtiferay, a bit of joyful mischief-making. Yes, we have to do some imagining between the lines. There are a number of queer people in my class this summer, and I brought in the Anna Margolin poem “Af a balkon” where she writes of two women leafing through an album of pictures. She doesn’t write about them loving each other, necessarily, but does write of them looking out over a red-orange sunset, and their hands meeting, as a man hovers over them like “a prekhtike ober iberike dekoratsye” [a splendid but superfluous decoration]. One can definitely read that in a specific way, likewise lots of Yiddish literature that has been turned around and upside-down, like so many treasure maps, to discover some latent queerness that may or may not be hidden in the text. But I think it’s nice, today, to write things that we don’t need to read between the lines in order to behold this kind of love and its physical realization, but to put it all right there, not between the lines, but rather, within them.