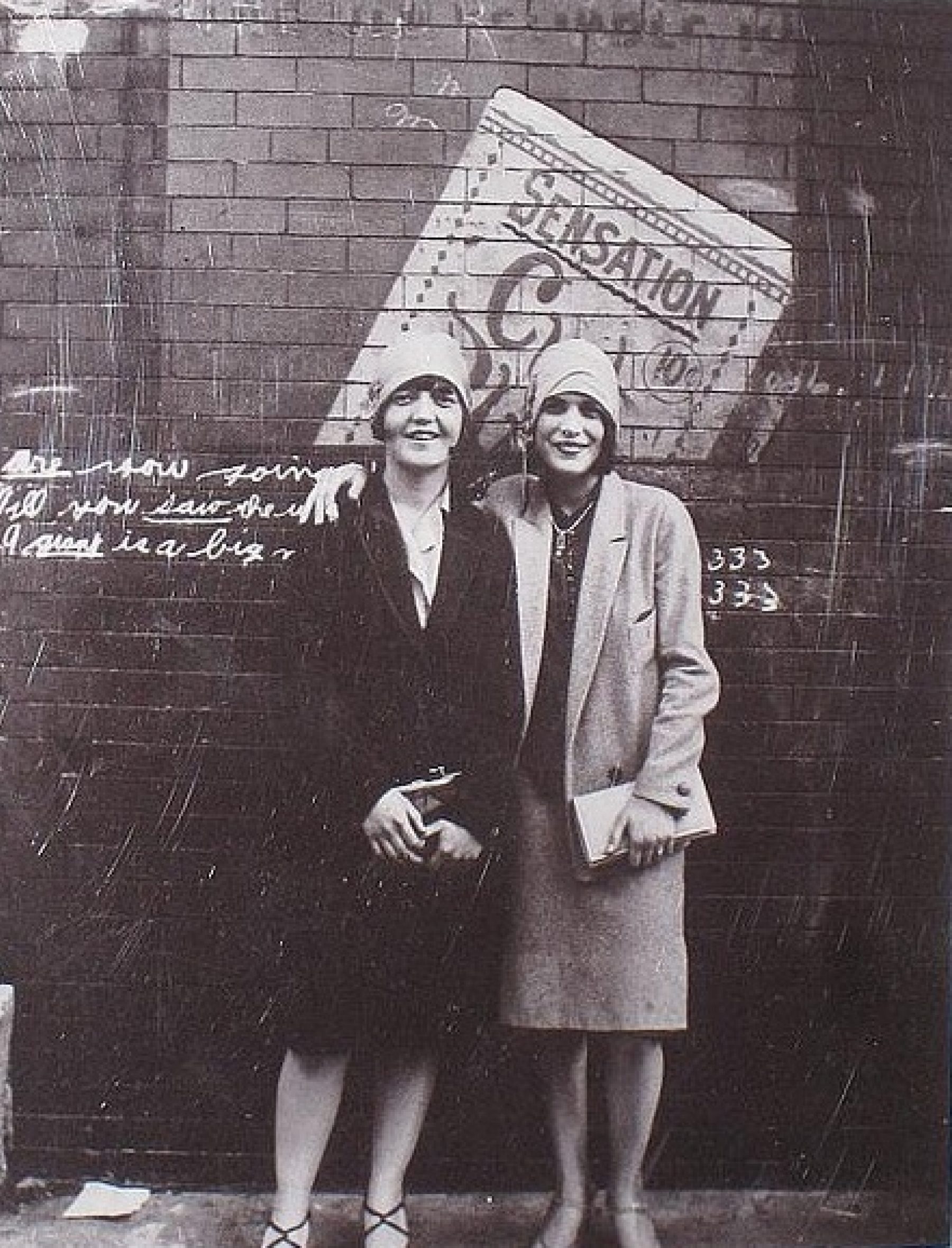

Yiddish Theatre Stars & Matinee Girls on the Move

Judith Thissen

You didn’t need to be the Great Gatsby to have a good time in the Roaring Twenties. Many Jewish immigrants in America also profited from the economic boom, and had more money to spend on shopping and entertainment. They also moved. In New York City, the rise of a middle class of Eastern European Jews profoundly changed the geography of Jewish life, as more and more second generation Jews and their parents left the city’s old immigrant sections to settle in newly-developed suburban neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens. Between 1920 and 1930, Flatbush, the Grand Concourse, Midwood, Sheepshead Bay, and Coney Island saw the number of Jewish residents jump between 250 and 700 percent. Young couples in particular were attracted by these middle-class neighborhoods with their tree-lined streets, large parks, and modern houses. Art Deco apartments with stained-glass windows and pink tile bathrooms belonged to the wonders of America as much as movie palaces and elegant department stores. Living and going out “in style” became an important marker of social achievement. It meant a break away from the Lower East Side, not only from the cramped tenements, but also from the Yiddish theatre.

As early as 1916, Tin Pan Alley commented on the changing taste of Jewish immigrant audiences in “My Yiddish Matinee Girl”:

When Rosie lived in Essex Street, she liked the Yiddishe plays

She was so sweet and gentile, all the actors she would praise

But since she moved up to the Bron-nex, she has got high tone

She gave up Thomashefsky and she took to Georgie Cohen [sic]

She’s now got lots of whims, since father’s business pays

From moving picture films, she changed to Broadway plays.

The lyrics of Addison Burkhardt’s song make fun of Rosie of Essex Street who loved the Yiddish theatre and nickel-and-dime pictures, but who then trades them in for Broadway musicals when her family moves up to the Bronx. Irish George M. Cohan (misspelled as Cohen!) is singled out as Rosie’s favorite star. But I am sure that she also must have loved to see a “high-class” vaudeville show at the Winter Garden or a “photoplay” at Roxy’s Rialto Theatre.

Cover for sheet music of songs from Hello Broadway (1919), a musical comedy by George M. Cohan. Source: Library of Congress.

Cover for sheet music of songs from Little Nellie Kelly (1922), a musical comedy by George M. Cohan. Source: Library of Congress.

As soon as the uptown managers discovered the Jewish “subway public,” they sought to further develop and retain the loyalty of this new clientele by integrating specific Jewish elements into the program, especially during Jewish holidays. But theatre-going was a year-round activity, so why not try to stage Jewish-themed musicals on Broadway? Big movies with Jewish stories already did very well at the box office in the early 1920s.

Among the first impresarios to venture into producing Jewish musicals were Albert Lewis and Max Gordon, two Polish Jews who had started out in vaudeville and then set up their own booking and production agency. In 1925, they asked Samson Raphaelson to adapt his short story, “The Day of Atonement,” for the stage, and they renamed it The Jazz Singer. Loosely based on the life of vaudeville star Al Jolson, who would play “himself” in the 1927 screen version by Warner Bros., the story dramatizes the struggle between Jewish tradition and American modernity, between first- and second-generation immigrants.

Jews are particularly attracted by plays in which the principal characters are Jews.

New York Herald (1925).

On September 24, 1925, The Jazz Singer premiered on Broadway with George Jessel in the leading role. With almost 300 performances in its first season, it was quite a hit. Nobody had expected that a play about Jews would do so well on Broadway. Jessel told Theatre Magazine that he owed his success “in great measure to the Jewish public.” According to the reviewer for the Herald Tribune, the show was “wholly unintelligible” for those who did not speak Yiddish and knew nothing about Judaism. And his colleague from The American Hebrew remarked that the audience of The Jazz Singer “had a queer look – for uptown. Some of the women were wearing schiedels [sic; wigs], a few of the men very orthodox beards.” It was apparently a very different crowd than the habitual Jewish Broadway fans, who in 1925 were more likely to be found at The Cocoanuts, the latest show of the Marx Brothers.

There is a Jewish public in New York as great if not greater than any other.

The American Hebrew (1926).

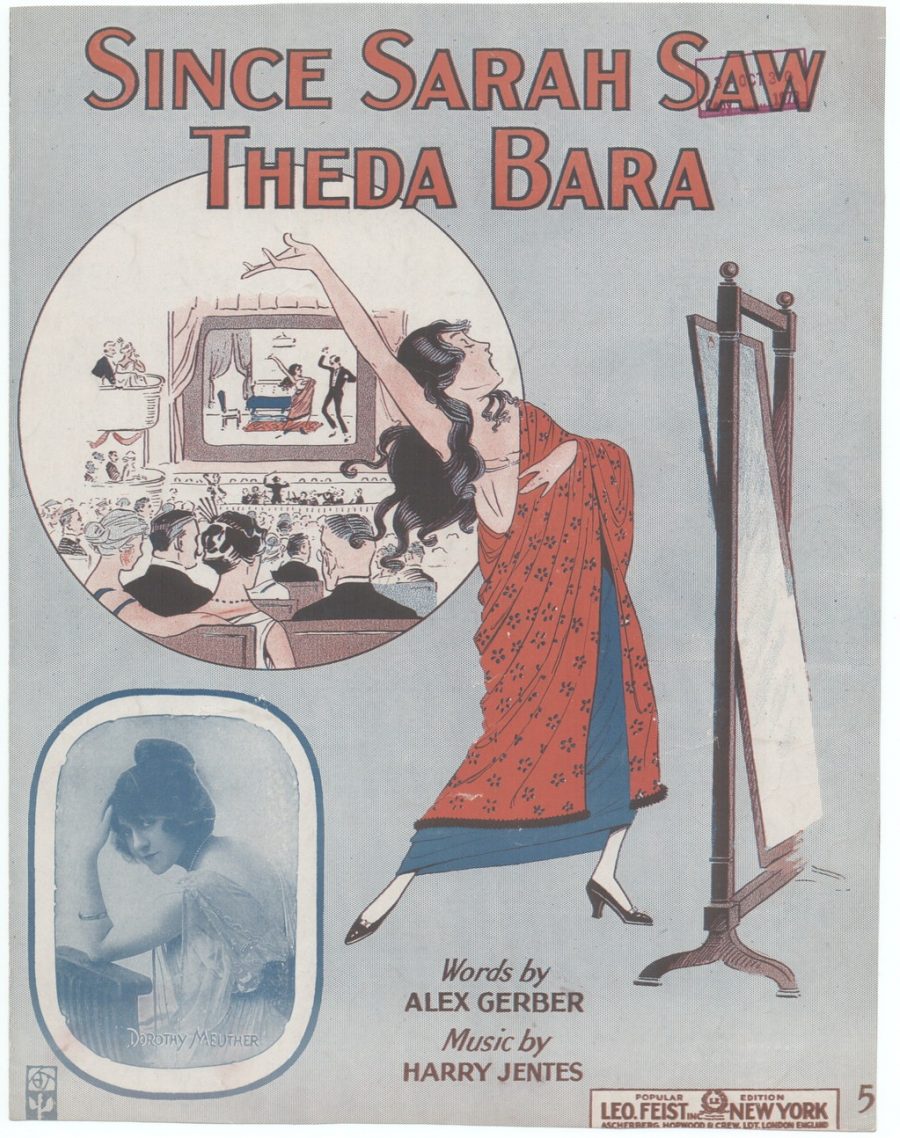

It is not surprising that there was a considerable Jewish audience for Broadway shows. Not only because Jews constituted almost a quarter of the city’s population in the 1920s, but also because many of them were already ardent theatre-goers. Since the late nineteenth century, Jewish immigrants and their children had gone in great numbers to the Yiddish theatre — first on the Bowery and later on Second Avenue. With the ongoing process of outward and upward mobility, it was normal that they began to abandon the downtown Yiddish theatre district. The young loved to go to Broadway for American musicals and movies. Given their growing visibility in the uptown theatres, it is hardly surprising that we find quite a few songs that recount their enthusiasm for mainstream entertainment. The fascination of Jewish girls with Hollywood stars is addressed with humor in Since Sarah Saw Theda Bara (1916), recently recorded by Lorin Sklamberg.

Sheet music for Since Sarah Saw Theda Bara, New York, 1916. Source: Library of Congress.

After seeing the “Vampire Queen” of the silver screen at a picture show, Sarah Cohn becomes “a very dangerous girl”: men fall for her rolling eyes and “devilish smile,” scores of sweethearts “hang around her door, and buy her all such fancy things—she’s got a dozen engagement rings.” Of course, we should take such lyrics with a pinch of salt, but they accurately position the Jewish matinee girl as a modern-day figure who has found her way in America.

Meanwhile, the older generation continued to favor Yiddish plays, but many of them preferred to see them in their own suburban neighborhoods instead of having to take a long subway ride to downtown Manhattan. Around 1900, all Yiddish theatres in New York City were located on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Twenty years later, the market was far more fragmented. Second Avenue was still the Yiddish Rialto, but quite a few Yiddish actors had followed their patrons to the suburbs –- first to Harlem, and later also to Brooklyn and the Bronx.

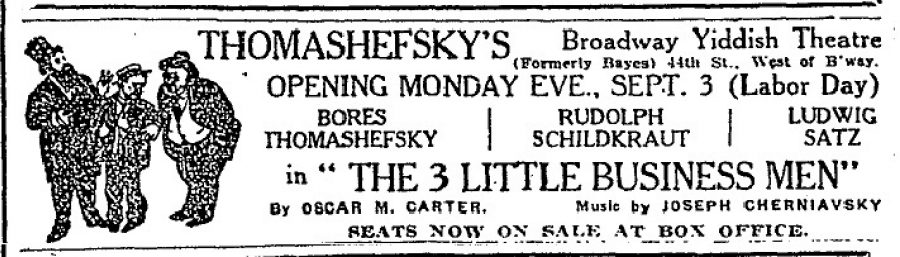

Some stars even sought to establish themselves in the heart of Broadway. The most ambitious and tragic effort in this respect was when Boris Thomashefsky decided to leave downtown for uptown. In June 1923, he took over the lease of the Nora Bayes rooftop theatre on 44th Street from the Shubert Brothers and renamed it Thomashefsky’s Broadway Yiddish Theatre. “The signing for the Bayes is in keeping with an idea to attract patrons from all the boroughs instead of confined to the Lower East Side,” Variety explained.

Boris Thomashefsky. Source: The Thomashefsky Project

Publicity for the new playhouse appeared in both the Yiddish press and the New York Times. The opening play was Oscar M. Carter’s Drey kleyne bizneslayt with music by Joseph Cherniavsky.

Thomashefsky’s Broadway Yiddish playhouse opened on Labor Day with standing room only, but a few months later it went dark. Right from the start, there were problems with uptown union rules and blue laws, which prohibited regular stage performances on Sunday. Despite protests from Thomashefsky and the Hebrew Actors’ Union, only “Sunday concerts” were allowed. This was a dramatic turn of events, because Sunday was the best day at the box office in the Yiddish theatrical business. Thomashefsky attempted in vain to teach his audience that a new show remained on the bill throughout the entire week. But Yiddish theatre-goers stuck to their old habits: on the East Side, the latest plays were only performed on the weekend, with repertoire productions performed from Monday through Thursday at cut-rate prices to members of immigrant organizations. So only on Fridays and Saturdays did the Yiddish Broadway Theatre play for a full house (at best). Thomashefsky even tried to attract patrons by offering a free taxi ride with each ticket purchased for a Monday-through-Thursday night show. A clever publicity stunt! But, as Variety remarked, “too heavy a proposition if the theatre were to pay by the clock for every patron commuting from the Bronx or the Lower East Side.”

Portrait of George Cohan. Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections.

By mid-November, Thomashefsky was back to the downtown practice of selling blocks of tickets for old plays at wholesale prices. He was now desperately looking to not further alienate his East Side fans. He also tried to recoup his losses by setting up a Yiddish vaudeville circuit with the same acts that he offered during the Sunday concerts. Unfortunately, it was already too late. The Broadway Yiddish Theatre closed down in March 1924. Thomashefsky was forced to file bankruptcy and never recovered from this setback. Rosie and her matinee friends continued to fancy Georgie Cohan.