Khane Braz / חנה בראַז

Khane Braz: three news articles

Yermiyahu Ahron Taub, Khane Braz

These translations (which were done by Yermiyahu Ahron Taub) are part of a series devoted to Yiddish actresses in the Holocaust, published to mark Yom Ha-Shoah and the eightieth commemoration of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Three pieces describe the career of dramatic artist Khane Braz (1895-1942, killed by the Nazis), an actor in the Vilna Troupe and a recitational performer of Yiddish literature. Born in eastern Poland, she lived in Vilna and left school at age twelve to go to work, supporting her parents financially throughout her life. Braz came to the Vilna Dramatic Studio in 1919 and joined the Vilna Troupe in 1920, where she distinguished herself as a serious actor and master of Yiddish diction. During the interwar period, she worked throughout eastern Europe including Warsaw, Riga, and especially the state Yiddish theatres of the Soviet Union. Her art and personality provided spiritual sustenance to children and adults in the Warsaw ghetto before she was murdered by the Nazis. 1

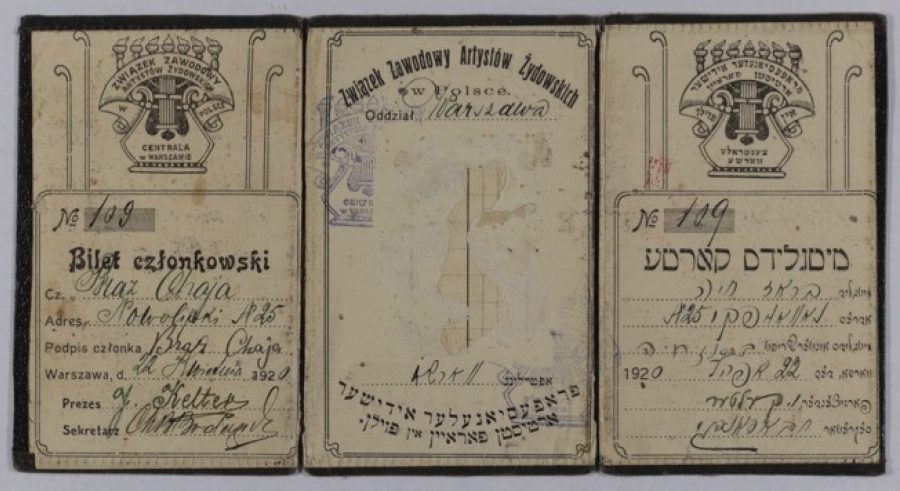

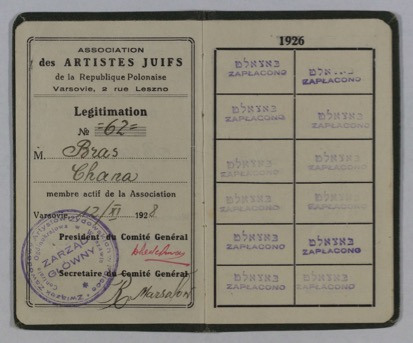

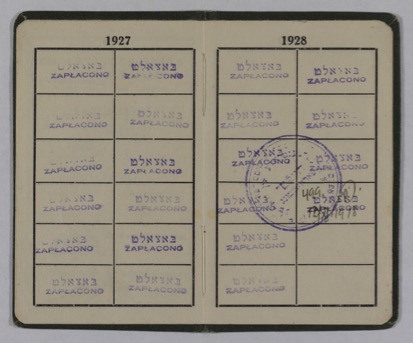

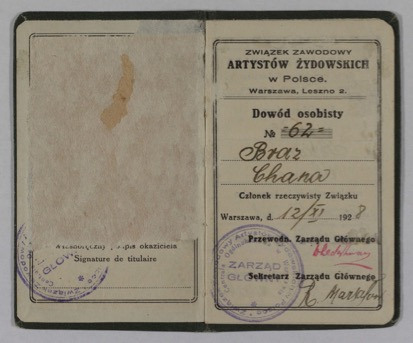

Membership card, folder 47, box 34, RG 26, Guide to the Records of the Yidisher Artistn Farayn (Yiddish Actors’ Union), 1909-1940, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerS….

Elkhonen Tsaytlin, “On the Performance of the Artist Khane Braz,” Undzer ekspres [Our Express], Warsaw, Tuesday, March 12, 1929, 6.

Last Saturday evening, we had the opportunity to get acquainted with one of the best Yiddish dramatic readers—the well-known dramatic artist, Khane Braz. Some years ago, Khane Braz was quite popular as a leading light of the Vilna Troupe—the previous, first incarnation of the Vilna Troupe, which wrote such a glorious page in the history of the new Yiddish theatre. Now Miss Braz is in Warsaw, and, unfortunately, she hasn’t had the opportunity to perform in a Warsaw Yiddish theatre for reasons that are utterly incomprehensible and require clarification. In any case, as far as one can tell, it is through no fault of the performer…

On Saturday, we saw Khane Braz, hitherto known only as a dramatic actor, distinguish herself as a recitational performer of new Yiddish literature. After Hertz Grosbard (1892-1994), Khane Braz is the finest interpreter of modern Yiddish poetry. Her recital emanated outward in a warm, soft tone that created a sense of intimacy and welcome and caused one to forget the gray surroundings. The wonderful poem of Moyshe-Leyb Halpern (1886-1932), “My Portrait,” and Kadia Molodowsky’s (1894-1975) “The Goy of the Potatoes” simmered splendidly with such a strong, vital dose of humor that it was truly a pleasure to behold. With what delicacy did she bring to life [Hayim Nakhman] Bialik’s (1873-1934) renowned poem, “Between the Rivers Peras and Khidekel”! We also heard a recital of [Dovid] Pinski’s (1872-1959) “David and Bathsheba.” However, that went on a bit too long.

Khane Braz absolutely should not neglect recitation. It doesn’t need to be the life calling for a good dramatic artist. Recitation—clear and crystalline—is itself a high form of word art. The field of Yiddish recitation has barely been mined. Only its first harbingers of spring have appeared!

Yiddish literature, as essential as air to breathe, needs individuals who will bring creative writing in its purest form to city and town alike. Khane Braz is most certainly one of those who can admirably spread this art form to Jewish settlements far and wide.

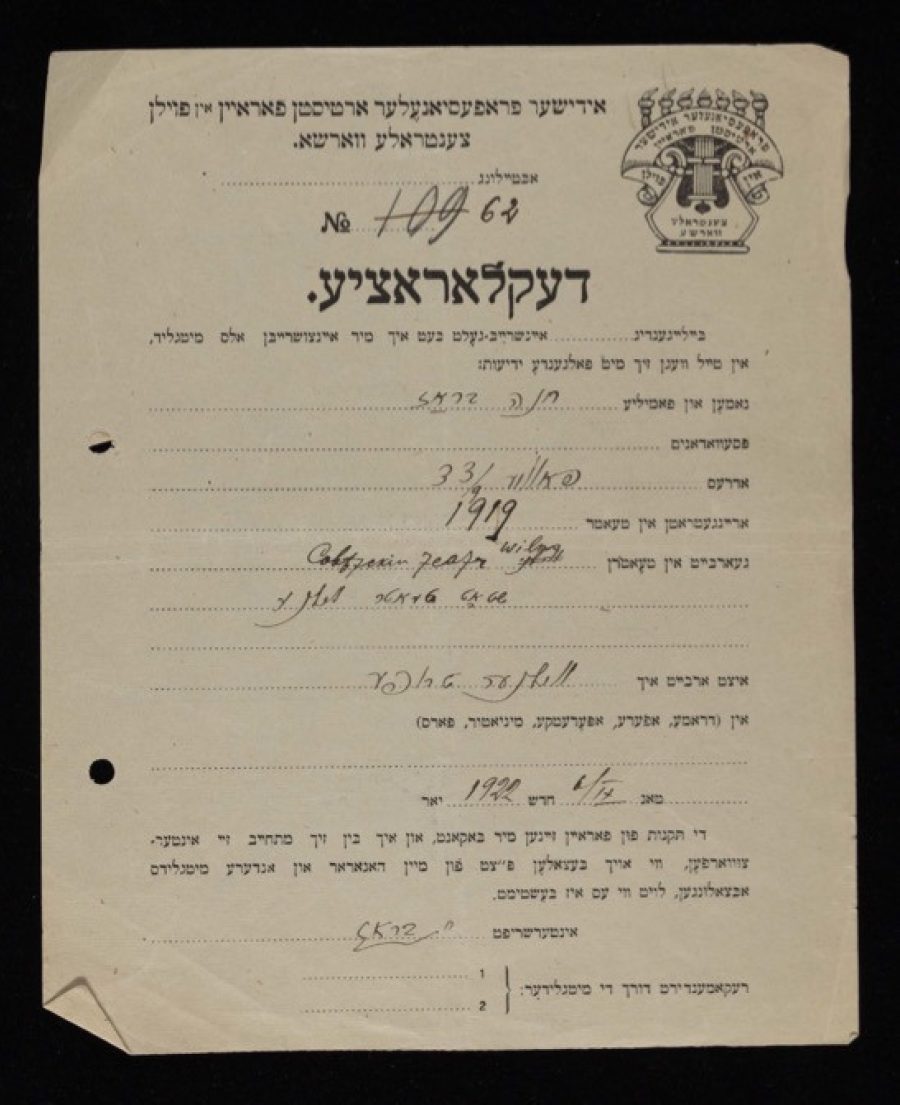

Registration form, folder 47, box 34, RG 26, Guide to the Records of the Yidisher Artistn Farayn (Yiddish Actors’ Union), 1909-1940, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerS….

Sh. Lev, “Khane Braz’s Word Concerts,” Literarishe bleter [Literary Pages], Warsaw. Friday, February 12, 1937, 10.

The word concerts of Khane Braz in the Warsaw Literary Union possess all seven graces. Khane Braz is not merely someone who recites; she is an actor, an interpreter, and a composer. Her performance is considered, with a breadth of knowledge and good judgement in the Lithuanian mold. Her diction is excellent. Braz has mastered a Vilna Yiddish, sonorous in its sound. Her stylizations are authentic, lively, and always with intentionality present. The character type is palpable in Khane Braz’s words. Whether she is speaking in the manner of a Vilna wife (Sholem Aleichem’s (1959-1916) monologue), or like Reb Yekhezkel Gombiner (one of Izi Kharik’s (1898–1937) creations), or actually like a flirtatious poet (“Madam” from Moyshe-Leyb Halpern), she always takes on the right tone, giving the appropriate furrow, the desired gesticulation. She softens, becoming childishly naïve when she reads the children’s stories of L. Kvitko (1890-1952) or K. Molodowsky.Khane Braz is an expert in literature. Her repertoire has an internal consistency of its own. She makes her selections from the most recent and best in Yiddish literature: Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, [Peretz] Markish (1895-1952), Izi Kharik, M. Kulbak (1896–1937), K. Molodowsky, L. Kvitko, and, of course, the ever-fresh Sholem Aleichem, and others. This is Khane Braz’s repertoire.

Khane Braz doesn’t chase after effect. She doesn’t believe in ending with a flourish of “fortissimo” to elicit applause. She is unassuming, serious, and sincere. Her revolutionary tones bring her out of the depths: without falsehood or exaggeration, and full of life and pain.

At a Khane Braz word-concert evening, one experiences genuine artistic delight and the pleasure of serious Yiddish poetic words, Yiddish words of seriousness and poeticism.

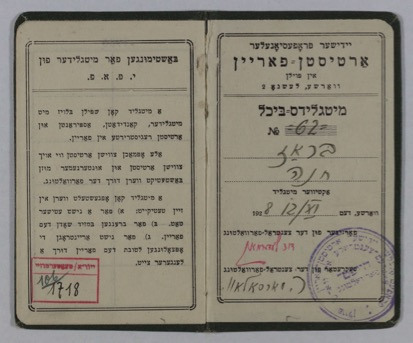

Membership booklet, folder 47, box 34,RG 26, Guide to the Records of the Yidisher Artistn Farayn (Yiddish Actors’ Union), 1909-1940, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerS….

Membership booklet, folder 47, box 34,RG 26, Guide to the Records of the Yidisher Artistn Farayn (Yiddish Actors’ Union), 1909-1940, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerS….

Membership booklet, folder 47, box 34,RG 26, Guide to the Records of the Yidisher Artistn Farayn (Yiddish Actors’ Union), 1909-1940, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerS….

Membership booklet, folder 47, box 34,RG 26, Guide to the Records of the Yidisher Artistn Farayn (Yiddish Actors’ Union), 1909-1940, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerS….

Jonas Turkow, “Khane Braz,” Excerpt from Farloshene shtern [Extinguished Stars], (Buenos Aires: Tsentral-farband fun poylishe yidn in Argentine, 1953), 206–209.

While still a student, Khane Braz made her initial foray into the theatre in a variety of amateur circles in her hometown of Vilna. Even at this tender age, her talents made quite an impression.

Shortly thereafter, she began to work in the theatre and received an invitation to join the Vilna Troupe in Warsaw as a professional.

From 1920 onward, Braz performed with the Vilna Troupe and toured with them abroad. She achieved considerable distinction in a wide range of roles, and people predicted a great future for her. Instead of resting on her laurels, she worked with absolute diligence, immersing herself in her roles, eschewing the path of least resistance. Theatre was sacred and precious to her. With considerable determination and youthful energy, Braz threw herself into the work of the theatre and remained open to all new possibilities. The more she searched, the less satisfied she was. She decided, therefore, to travel to Soviet Russia, where Yiddish theatre was then flowering.

For several years, she worked in Jewish State Theatres in Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Odesa. There she assumed a leading position, garnering acclaim in all of the productions. People realized that she had greatly matured and had become a first-rate dramatic actor. But in those cities as well, Khane Braz’s ever-restless, striving spirit did not find the contentment for which she searched and longed.

She returned to Poland, where she remained until the end of her life. She traveled around the provinces performing with numerous dramatic companies and giving “word concerts.”

When the war broke out, Khane Braz was in Warsaw. After the German invasion, she started to work in the realm of Jewish communal self-help. As soon as artistic productions began, she became the heart and soul of the theatre organized for children in the Warsaw Ghetto. She appeared there with Ayzik Samberg (1889–1943, murdered by the Nazis), Avrom Kurts (b. 1893-1942, also murdered by the Nazis), Michał Znicz (1888–1943), and with the composer Eva Vesbi.

With body and soul, Khane Braz threw herself into this important valuable work and, in the process, brought much joy and consolation to the most unfortunate of all the unfortunate people in the ghetto—Jewish children. She quickly became beloved by the children. The moment “Auntie” Braz—that’s what the children called her—appeared anywhere, she was surrounded by a contingent of children and proceeded to tell them stories of a better world and thereby fortified their spirits. She gave them encouragement and hope.

In this type of work, she finally found—as she herself said—a sense of contentment in her restless, lonely life.

Khane Braz found purpose not only with official productions that were organized for the children in the ghetto. She went directly to their homes, forging an immediate link with the children.

In each house in the Warsaw Ghetto, a “children’s corner” was established—a center where the little ones received not simply better nourishment, but also spiritual sustenance. In the evenings, they engaged in various forms of entertainment, conversations, songs, and games. The adults worked hard to create a warm atmosphere for the children and thereby detach the young souls from the arduous daily life surrounding them.

Alone and isolated from her family and loved ones in Warsaw, Khane Braz assumed a large portion of the responsibility of this magnificent work.

Khane Braz also performed with great success for adults in the ghetto, lifting their spirits with her fine, carefully curated repertoire of recitations.

However, despite her considerable success and vital work, her life in the ghetto was quite difficult. Sure, her efforts greatly intrigued the few friends she had in the ghetto, who assisted her practically whenever they could. But when the time came for each person to think about his or her own life and limb, they forgot about Khane Braz…

Only when the first wave of the deportation of Jews was over did they notice that Khane Braz was among the initial Jewish deportees… She was too weak, too resigned to go into hiding. She lacked the strength to elbow her way through the grueling, challenging times that crept up on our people who have been bitterly tested.

Along with her child spectators, adult admirers and friends, and numerous professional colleagues, Khane Braz—the fine and lonely Yiddish actor—suffered the fate that was meted out to eastern European Jewry.

She was among the first in the gas chambers of Treblinka…