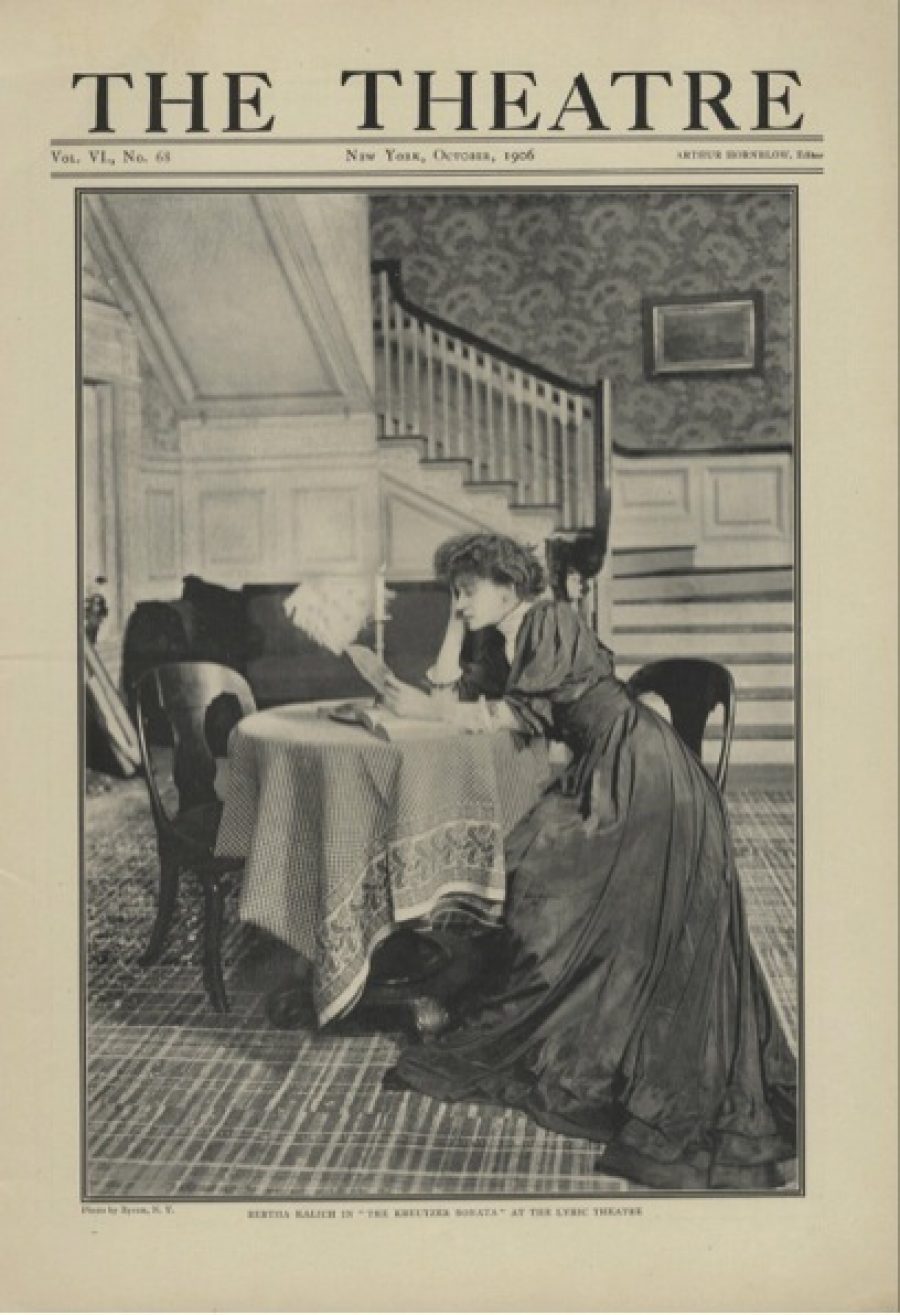

Bertha Kalich (far left) and cast in the Broadway production of The Kreutzer Sonata, 1906.

Yiddish Drama on the Broadway Stage

Stefanie Halpern

On July 6, 1919, the New York Tribune reported that A.H. Woods, a prominent American theatre impresario, purchased the complete rights to 500 Yiddish play scripts, which had been presented on the Yiddish stage between 1909 and 1919. This included works by Jacob Gordin, Leon Kobrin, Zalmen Libin, Max Gabel, and Joseph Lateiner. 1 Woods, a Budapest-born Jew who came to New York as a child and grew up on the Lower East Side, straddled both the uptown and downtown milieus; in 1909, for example, he rented space for presenting weekday English-language melodramas at Jacob P. Adler’s Grand Street Yiddish Theatre, located at the corner of Chrystie and Grand Streets. 2 With his bulk purchase, Woods intended to capitalize on the “growing recognition of the Yiddish theatre by the English speaking press and public” by translating and adapting these plays and presenting them on the English-language stage. Woods believed he had found an “inexhaustible mine of entertainment,” and even decided to purchase the rights to produce in English any new Yiddish play performed over the next ten years. Throughout his lengthy career, Woods produced nearly 200 plays on the American English-language stage. However, there is no clear information on just how many Yiddish plays he produced, as he often passed a translation as an original English-language work with no mention of provenance. Woods’s belief that the plays, players, and practitioners of the Yiddish theatre would make “valuable additions to the American English-language stage” is impressive. 3 And it would prove prescient.

From its beginnings, New York’s Yiddish theatre intersected with the mainstream English-language stage, with reviews of Yiddish plays appearing in the English-language press as early as 1884. As the Yiddish theatrical establishment grew and proved itself to be a serious institution, English-speaking journalists and actors began to recognize in the Yiddish theatre something that was absent from uptown stage productions. For example, in 1907, a reviewer for the Sun noted, “In the Yiddish drama have been discovered the force, passion, and, above all, the temperament that the American drama of today seems more conspicuously to lack.” 4

Bertha Kalich as Ettie Friedlander, Otto Sarony Co., 1906, The Museum Of The City Of New York.

The first Yiddish play to be translated, adapted, and staged on Broadway was Jacob Gordin’s Di kreytser sonata [The Kreutzer Sonata]. Adapted by Jacob Gordin from a novella by Tolstoy, The Kreutzer Sonata revolves around the tragic fate of Ettie Friedlander, a bourgeois “fallen woman” who, pregnant by her gentile lover, is forced by her father to marry a Jewish musician and move from Russia to America. It is a loveless marriage, and when Ettie finds out that her husband and sister are having an affair, and that he has secretly fathered her sister’s child, Ettie murders the couple and mutilates herself. Gordin’s play opened in 1902 to Yiddish audiences at the Thalia Theatre on the Bowery. Written for and starring Bertha Kalich, The Kreutzer Sonata ran in Yiddish for over 300 performances, and it was one of Gordin’s most financially successful plays. American producer Harrison Grey Fiske commissioned playwright Langdon Mitchell to adapt The Kreutzer Sonata for a production staged by the Manhattan Theatre Company with Bertha Kalich in the role she had originated on the Yiddish stage. Mitchell was regarded as a serious playwright who did not shy away from addressing social concerns and sensitive subject matter not otherwise seen on the commercial stage.

The staging of The Kreutzer Sonata in English must be seen within the context of an American theatre in the throes of upheaval and change. American critics lamented the state of the American theatre, accusing practitioners of pandering to the lowbrow desires of the audiences. Many theatre people also blamed the playwright for the sad state of affairs of the American drama, complaining that “the money fever has seized many of our fashionable playwrights, and we find most of them wasting their talent on the veriest hack work, turning out two or three plays a season for so-called stars, thus prostituting themselves and their art in efforts that usually result in failure.” 5 Critics hoped that the American drama could reach greater heights so that it not only interested audiences but instructed as well.

The Kreutzer Sonata was widely regarded as a new form of dramatic writing totally foreign to the American stage, as it represented a break from the standard melodramas that found greatest favor amongst Yiddish and English audiences alike. Gordin, “a singularly gifted playwright,” was writing within “a type of a school of drama with which, as yet, the American public is almost totally unacquainted.” 6 For this reason, critics looked to Gordin as one of the playwrights who was ushering in a new age of American playwriting; his leading role in the “development of a new phase of the American drama” interested American, English-language critics even more than the play itself. 7

The Theatre cover page featuring Bertha Kalich in the Broadway production of The Kreutzer Sonata, October 1906.

Unlike the plot of melodramas that simply pitted good against evil, with the stock characters of the hero and the villain representing good and evil, The Kreutzer Sonata presented complex and dynamic characters whose morality vacillated, who could err and remake themselves, and whose evil intentions belied their beautiful exterior. Rather than giving over the voice of the woman to a young, fair, naïve heroine with no real agency, whose body became the battleground upon which the hero and the villain fought for control, Gordin had Ettie represent the voice of the modern woman: intelligent and ultimately rebellious, and unable or unwilling to adhere to the strict bounds of a patriarchal society.

Another criticism lobbed against the dramas presented on the American stage was that they were mainly foreign imports. At the turn of the century, there were few important American dramatists, and in many instances, though written in America, plays were European in subject matter. Those critics who had tired of an American stage whose only serious dramas were borrowed from the stages of Europe saw Gordin as a writer who had the ability to draw upon the material of American life. If the critique of translations of foreign plays was that they were not rooted in American life, critics looked at The Kreutzer Sonata as dealing with American themes: intergenerational conflict and the upending of parental authority; the divide between progress and stern obedience; intermarriage; immigration. Though The Kreutzer Sonata contained many Jewish elements, part of its appeal was that its themes were also relevant to life in America. Gordin’s drama was considered “a powerful study of the influence of change in environment upon a family group transplanted from Russia to this country.” It was a play that highlighted for a modern audience “the disintegration of family traditions and ideals under the stress of the feverish commercial life of a great city like New York coincident with the inexorable penalty attached to a forced marriage between two people who do not love each other.” 8 Once adapted into English, The Kreutzer Sonata became a blend of both European and American, appealing to the American audience not only because they recognized something native in it, but because it became a means through which they might begin to understand the growing immigrant community, commenting on American society both from within and without. The play became a vehicle through which the American theatergoer could begin to understand an immigrant community that seemed so different.

Over the next fifty years, plays by major Yiddish writers continued to be translated and produced on the Broadway stage. By mid-century, even as the Yiddish stage declined in viewership and cultural output, it still exerted an influence on Broadway through the adaptation of Yiddish plays into English. Paddy Chayefsky’s 1959 The Tenth Man, for example, is a modern-day adaptation of Sh. An-sky’s Der dibek (The Dybbuk, first produced in 1920). Chayefsky replaces the shtibl of Eastern Europe with a nearly defunct synagogue in a New York suburb, and has a group of old Jewish men attempt to excise a dybbuk (spirit) from a young, assimilated woman. On stage, with two worlds colliding, he presents the image of the audience itself—second- and third-generation American Jews struggling with a nearly foreign cultural and religious past, the type of Jews who would have also resonated with the audience in 1989, when the play was revived at Lincoln Center. The Tenth Man, hailed as Chayefsky’s greatest achievement, would go on to be nominated for three Tony Awards in 1960, including Best Play.

Contemporary American playwrights and producing companies have continued to engage in a dialogue with the Yiddish theatrical tradition: Tony Kushner’s A Dybbuk, which premiered in 1997 at the Joseph Papp Public Theater; a production of The Dybbuk at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2000; a re-imagined God of Vengeance by Pulitzer Prize winning dramatist Donald Margulies (2002), now set in New York; a 1948 Broadway production of H. Leivick’s The Golem, and the Manhattan Ensemble Theatre’s 2002 production starring Tony-nominated actor Robert Prosky. Paula Vogel’s Indecent, which extrapolates from the contents and history of Sholem Asch’s God of Vengeance to reflect on the fate of Yiddish culture more broadly, thus fits into a conversation between Yiddish drama and Broadway that has been with us for over a century. As playwrights continue to borrow, adapt, and reconstitute the Yiddish drama for a new American audience, the Yiddish theatrical tradition remains an important component of the American stage.

Notes

-

1The purchase also included plays by the following writers: Moses Richter, Nachum Rakhov, S. Kornbluth, Samuel Steinberg, Isidor Lilian, and William Siegel. From “Mr. Woods' Large Purchase,” The Washington Post, July 6, 1919, L5.

-

2“Actor Adler Hurt in a Theater Fight,” New York Times, April 27, 1909, 20.

-

3“A. H. Woods Buys Output Of Yiddish Playwrights,” New York Tribune, June 30, 1919.

-

4“At a Yiddish Theatre: The Plays and Players,” The Sun, September 15, 1907.

-

5Quoted in Roger Leon Meersman, “The Theater Magazine: An Analysis of Its Treatment of Selected Aspects of American Theatre (PhD diss., University of Illinois, 1962), 15.

-

6“Jacob Gordin and the Kreutzer Sonata,” Current Opinion, July 1906, 20.

-

7Ibid.

-

8William Mailly, “The Season’s Social Dramas,” The Arena, July 1907, 40-41.