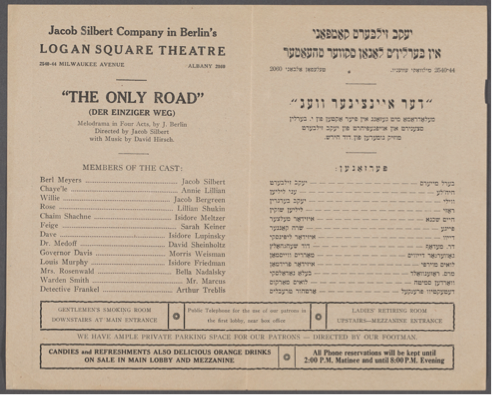

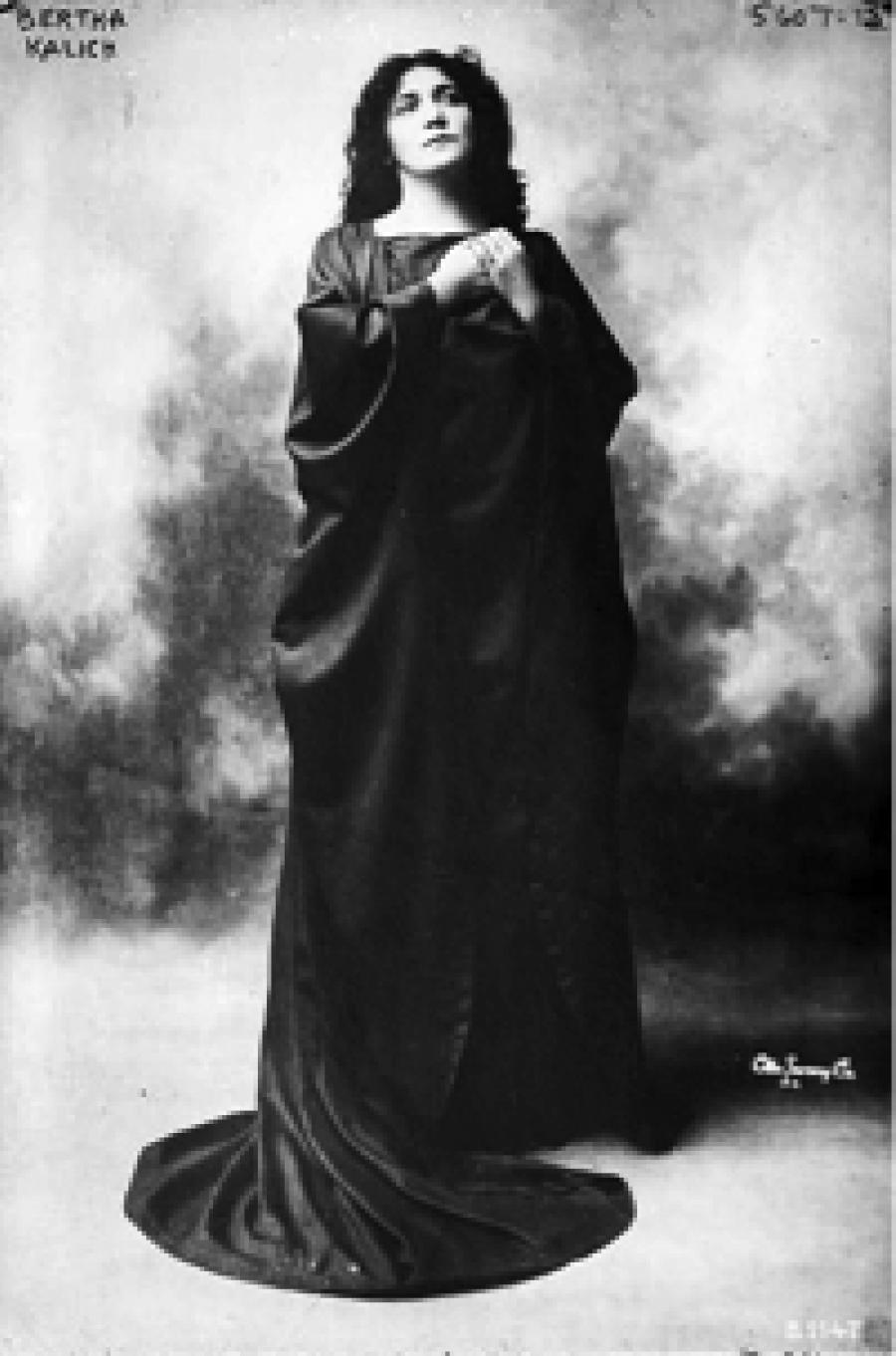

Bertha Kalich, Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library.

“I would have run away, but there was only one path for me - onto the stage”: Bertha Kalich at the Romanian National Theatre, Part I

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

BERTHA KALICH (1874-1939) was a great actress on the Yiddish and English-language stage. Born in Lviv, Ukraine, she was a prima donna in Gimpel’s Theatre and throughout Europe before coming to America. “Mayn leben” [My life], her serialized memoir (written with Tsvi-Hirsh Rubinshteyn), was published in the New York Yiddish daily, Der Tog, from March 7-November 14, 1925.

In 1894, Kalich was asked to audition for the Romanian National Theatre, in a climate of deep antisemitism, xenophobia, and Romanian nationalism. Kalich became the first Jew of any gender or nationality to perform there. Here, she describes her debut.

The rehearsals at the National Theatre lasted several weeks, and each one took a heavy toll on me. At each rehearsal, I heard new rumors tailored especially for me. Once they insinuated that the director, Stefanescu, had decided not to stage La dame blanche (The White Lady), but another opera in which I would not be able to sing; another time a rumor spread that the liberals had united with the conservatives, so that I no longer had a case.

Stefanescu was the leader of the liberal party, which was always looking for new energy for the theatre, and it did not make a difference what nationality the artist was, as long as he was really an artist. The second group, the conservatives, had a narrow, nationalistic conception of how theatre must be run. Their motto was that only Romanians should sing in the Romanian National Theatre, and that foreigners must not set foot on their stage.

Of course, the attitude towards artists from foreign countries was a thousand times sharper and narrower towards the artists from a “Mosaic” background. Romania later became a nest of antisemitism, and one can clearly understand that in their theatre, they had barred the doors with a thousand locks for the children of the Jewish people.

Even the liberals, who did want to attract new, foreign energies, also looked crossly at Jewish artists, as great and talented they may have been.

1875 cartoon from Ghimpele, an anti-semitic Romanian newspaper.

The people in the theatre also implied that it was not nice for a Galician-Jewish girl to sing for the king, and that he would be greatly insulted by this. They spread a rumor that Madame Valadya had refused to perform with me, and demanded that another actress would sing instead of me. They spread more and more rumors and insinuations to embitter my young life. I heard these day after day, but still I managed to endure.

What bothered me the most was the actress who was supposed to play my role. She was, to begin with, a great antisemite, and she could not get over the pain that a “jidanca” [pejorative word for a Jewish woman] would take her place. She revolted and protested, but Stefanescu did not want to rescind his decision.

At that time, the National Theatre was in serious trouble. They lacked great artists, and the Jewish public were more likely to spend their time in a lowbrow music hall, or at the Jignitsa [Yiddish theatre], than at the opera. The theatre world breathed Jew-hatred, and Jews knew they were tolerated only because their money had no nationality.

The day of the first performance neared. Posters and newspapers made it known that the new opera La dame blanche, would feature familiar stars, and a new singer: Madame Bertha Kalich.

Emile Vernier, Engraving of the opera La dame blanche. The “white lady” appears.

I feared a great failure, and that the National Theatre would be my Waterloo… From time to time, it occurred to me to feign illness, but I gritted my teeth. I would fall as a hero, not a fledgling. I did not back down.

I was backstage in my dressing room when a new cloud appeared in my already stormy sky. Dovid Hirsh 1 gave me the bad news that a crowd of students had purchased tickets for tonight’s performance, loaded down with rotten apples, oranges, and potato peels. Another group, hired by several theatre people, was preparing to do the same, but it meant nothing, and I would sing my role as it was meant to be.

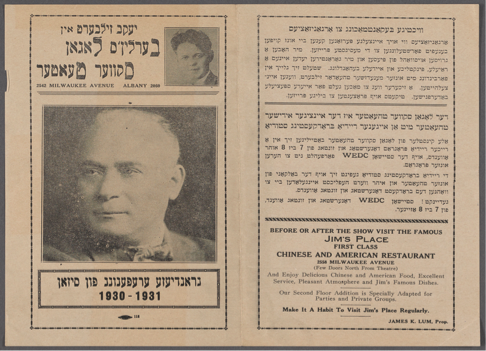

Dovid Hirsh (David Hirsch) later composed music for the Yiddish theatre in Chicago, such as this production of Der eyntsiker veg (The Only Road) in 1930.

Dovid Hirsh (David Hirsch) later composed music for the Yiddish theatre in Chicago, such as this production of Der eyntsiker veg (The Only Road) in 1930.

Withdrawing at the last minute was nearly impossible. Jews had suffered from antisemitism much more I had, and why shouldn’t I, the artist, also pay my debt to Jew-devouring humanity?

When they raised the curtain, my heart thumped, my hands trembled, and my knees bent, and I felt like I was about to fall. I had eaten nothing all day, so that my voice would be pure. But the fasting weakened me so much that I began to doubt whether I would have the strength to perform. My head was whirring with thoughts of the rotten apples and onions that would meet me onstage, and I had already resolved how to deal with the first rotten onion that reached the stage…

And that’s how I stood, in desperate straits, leaning against a wall backstage and looking at the notes of my first aria. The orchestra played the prelude. The greatest moment in my life arrived.

Suddenly, a nervous voice yelled in my ear:

‘Kalich! On stage.’

The words were spoken indifferently by a stagehand. His iron voice had a remarkable effect on my mood; he was the hangman preparing my scaffold, and I must obey. Now they are going to kill Bertha Kalich: soon I’ll become a heap of cold earth; soon I will cease to exist…

The last note of the prelude. The moment came when I had to step onto the stage of a royal theatre, and in the audience hundreds and hundreds of my enemies were loaded down with rotten onions and rotten oranges - a gift for the new artist…

The conductor gave me the signal, and I began to sing from behind the curtain. The theatre was so quiet that you could have heard the buzzing of a fly. My voice carried to the great hall, and I felt a fire underfoot. Even now it seems that I might have run away when I could, but I was in a predicament, and there was only one path for me - onto the stage….

‘Onstage!’

I obeyed the command of the iron voice. I didn’t walk, but swam out in a light, gracious movement to the center of the stage and sang my aria….

Glittering eyes looked up and devoured me. But I didn’t see,I didn’t hear. I forgot everything and sang diligently, with devotion, with love and with heart. And my song swung, and rolled and flowed over the entire theatre and embraced everyone. The last note came. My voice became lovelier, purer, and stronger.

A glass negative from the George Grantham Bain Collection in the US Library of Congress. Identification provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards, caption unverified. Circa 1898-1910

The finale came. No, no, dear reader, don’t worry your heart! Not one rotten apple fell on the stage. The theatre resounded with applause. From the loges they threw roses, narcissus, and white lilies like the wings of angels …

It was a moment of great happiness, but I could not process what had happened and continued playing my role; I sang another aria and thought of just one thing: the stage.

It was only after the first act, backstage with my husband, mother, and friends, as they began kissing me and weeping over me, that I understood that I had not sullied my name and my people. The Jewish girl from Galicia showed that she was an artist, who can and may perform not only on the poor Yiddish stage, but on the world-stage among the greatest artists and for an aristocratic, Christian audience.

To be continued…

© The New York Public Library