Bertha Kalich, Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library.

“I would have run away, but there was only one path for me - onto the stage”: Bertha Kalich at the Romanian National Theatre, Part II

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

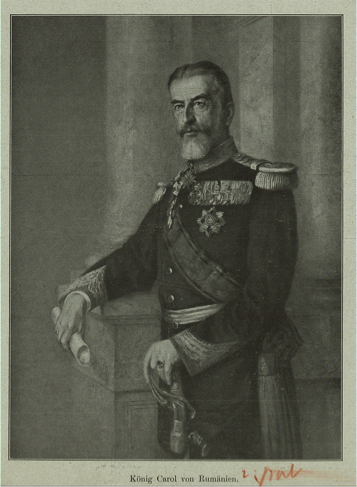

BERTHA KALICH (1874-1939) was a great actress on the Yiddish and English-language stage. Born in Lviv, Ukraine, she was a prima donna in Gimpel’s Theatre and throughout Europe before coming to America. “Mayn leben” [My life], her serialized memoir (written with Tsvi-Hirsh Rubinshteyn), was published in the New York Yiddish daily, Der Tog, from March 7-November 14, 1925.

This is part II of II in a series of posts dedicated to Bertha Kalich. The previous installment is found here.

When I finished the performance, I kept asking Spachner

1

and Hirsh,

2

“where did the rotten onions go? And what did they do with the rotten apples?” But neither Spachner nor Hirsh could answer my questions. They just explained to me that the students had clapped “Bravo” instead of throwing “fruit” at the stage.

We didn’t sleep that night after the performances. We headed off to a big restaurant and discussed only my great success. They told me that the greatest people of Bucharest had been in the theatre, and that they were amazed not only by my singing and acting, but by my Romanian accent, which was nearly perfect.

And truly, the little Romanian I learned caused a sensation. In total, I managed to learn the language excellently in only a few weeks. Aristizza Romanescu, who was one of the really great actresses, attended my first performance, and she predicted that I would be an international sensation and one day occupy a most prominent place on the stages of the world.

Aristizza Romanescu was a leading Romanian tragedienne.

Her words gave me much courage. She was considered to be the greatest tragedienne of that time, and her word was considered worthy in theatrical circles.

Soon after my first performance, I entered Bucharest’s high society. The Jews looked at me with great respect, and I was a guest in the finest Jewish homes.

I suddenly felt that I had become the central figure everywhere I went.

But my grandeur didn’t last long…

Never in my life did I experience hatred for Jews stronger than when I began performing in the National Theatre in Bucharest. The aristocrats who greatly enjoyed my singing felt nevertheless, that their “holy place” must be “Jew-free.” The name “Bertha Kalich” disturbed their peace, and a quiet, but intense, propaganda campaign began to rid their theatre of the “non-Romanian” element.

An even bigger propaganda campaign than that of the aristocrats was begun by the theatre’s employees. On one side, was Bachman the apostate, and on the other, the actress whose role I had taken; never did they cease putting obstacles in my path. It got to the point where my husband was threatened with a scandal if he didn’t remove me from the theatre. Several of my friends there advised me to stand strong and to fight. Other good people advised me to do the opposite – to run far away.

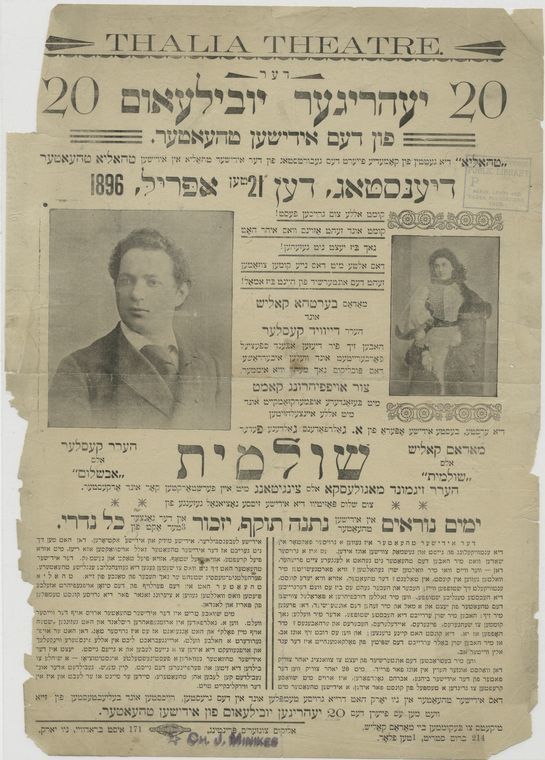

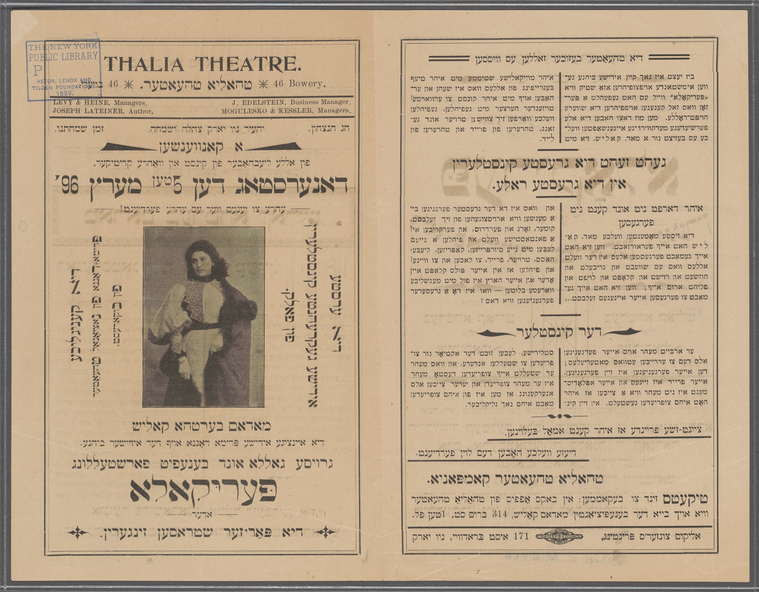

Bertha Kalich later worked for Joseph Edelstein at the Thalia Theatre in New York, pictured here in 1904. NYPL Digital Collections.

Bertha Kalich as Miriam in the Kreutzer Sonata and as “Mona Vanna.” NYPL Digital Collections.

At one point, Madame Vladaya entrusted my husband with a secret. Without ceremony, she told him, “They want to murder your wife. Protect her.” She revealed to him the theatre workers’ entire plan. At any moment they would poison my water, or send me poisoned flowers, and I would die from their scent. If my enemies did not succeed by those means, then a big lamp would day fall on my head “by chance,” or through a similar coincidence my clothes would catch fire.

Once, when I was walking with my husband in the Jewish quarter, we met an acquaintance who had a brother, Joseph Edelstein, in New York who was really something. He told us that Edelstein had his own Yiddish theatre, that he was very rich, and that in a few days he’d be visiting Bucharest.

Thalia Theatre production of Shulamis (1896). NYPL Digital Collections. Kalich is on the right hand side; opposite her is David Kessler, a longtime co-star and colleague.

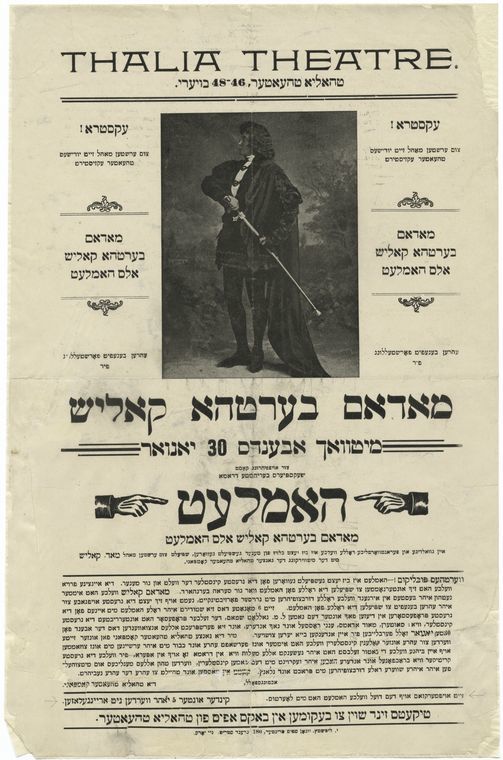

Bertha Kalich as Hamlet at the Thalia Theatre in New York (managed by Joseph Edelstein). NYPL Digital Collections.

Pericola at the Thalia Theatre. NYPL Digital Collections.

At the time, Edelstein managed the Thalia Theatre, a leading Yiddish theatre in New York. Edelstein had come from America especially to bring me over. He made no secret of it, and soon insisted to me and Spachner so persistently that getting out of this uncomfortable situation became a problem for me. “You’ll get rich! You’ll have palaces! It’s your America!”

Give up the National Theatre? Oh, no. That I couldn’t do. It was true that anti-semites were eating my heart, it was true that the hatred against me grew from day to day, and it was perhaps also true that that I wouldn’t be able to withstand for long the torture and torments of my opponents. But to give up a position in life, to give up the beautiful dream of a young artist, to unfurl the white flag and retreat from the battlefield - I couldn’t convince myself to do it.

Edelstein’s persistence was stronger than my stubbornness, though, and when Spachner and my parents began strongly talking me into it, and when they began shouting angrily at me, I began to consider the matter anew.

One evening I returned from a performance where I had survived all seven levels of hell. I was so disappointed by how I had been treated that in my heart I decided to accept Edelstein’s proposal. I had to discuss with Spachner how to tell the directors of the theatre that I wanted to end the contract because I was going to America. Spachner understood that I was close to giving in…

I went to the theatre to get my friends’ opinions of my plans. I also wanted to find a way to discreetly break my contract, so that there would be no talk in town. When I arrived at the theatre, one of the people from the office ran to tell me that next Friday the king and princess (who later became the queen) were coming to the performance, and that I would have the opportunity to perform for them. I was so surprised by this news that I forgot why I had come, and immediately ran home to tell my parents of my good fortune.

If my singing pleased the king, my ambitions would be realized. And if he would just say a good word about me to his court, I would be a recognized artist of the National Theatre! Just let him clap “Bravo” and all the antisemitic agitation against me would stop immediately. I was in seventh heaven, full of pleasure and anticipation, and I didn’t even want to think about what Edelstein had talked over with me.

King Carol had suddenly meddled with Edelstein’s business and ruined his plans, and Edelstein was not happy. But he did not lose heart — just the opposite. He began trying to convince me even more strongly. Edelstein promised to bring my husband and parents to America; he promised that he’d outfit us all with clothing, but that we should leave immediately.

And we settled it. I would abandon the king in Bucharest and flee before Friday with Edelstein to America. It seemed to me that with this step I was burning all bridges, and that I would never again be so close to my goal as I was then. America was a fantasy, and here I was burying a living reality. There, across the sea, palaces and gold awaited me. And here I was abandoning something that was a million times dearer to me — my art. It never occurred to me that I would have to leave in such a way from the city that gave me so much.

That was Thursday evening, and Friday I was supposed to be performing for the king. I wrote a letter to [the director] Stefanescu and let him know I would no longer be performing, and that due to the terrible anti-semitism that reigned in his theatre, I needed to break my contract and flee Bucharest. The letter was sent before we went to the train station, and Stefanescu received it Friday, when we were already far from the Romanian border.

© The New York Public Library

Notes

-

1Leopold Spachner was Bertha Kalich’s husband, and later her business manager.

-

2Dovid Hirsh, b. 1870, studied synagogue and vocal music and worked as a music director and composer for the Yiddish stage with playwrights Avrom Goldfaden, Joseph Lateiner, and Moyshe Hurwitz, among others. He also worked as a choir director and soloist in the Romanian National Theatre, where he was successful in arranging Bertha Kalich’s performance.