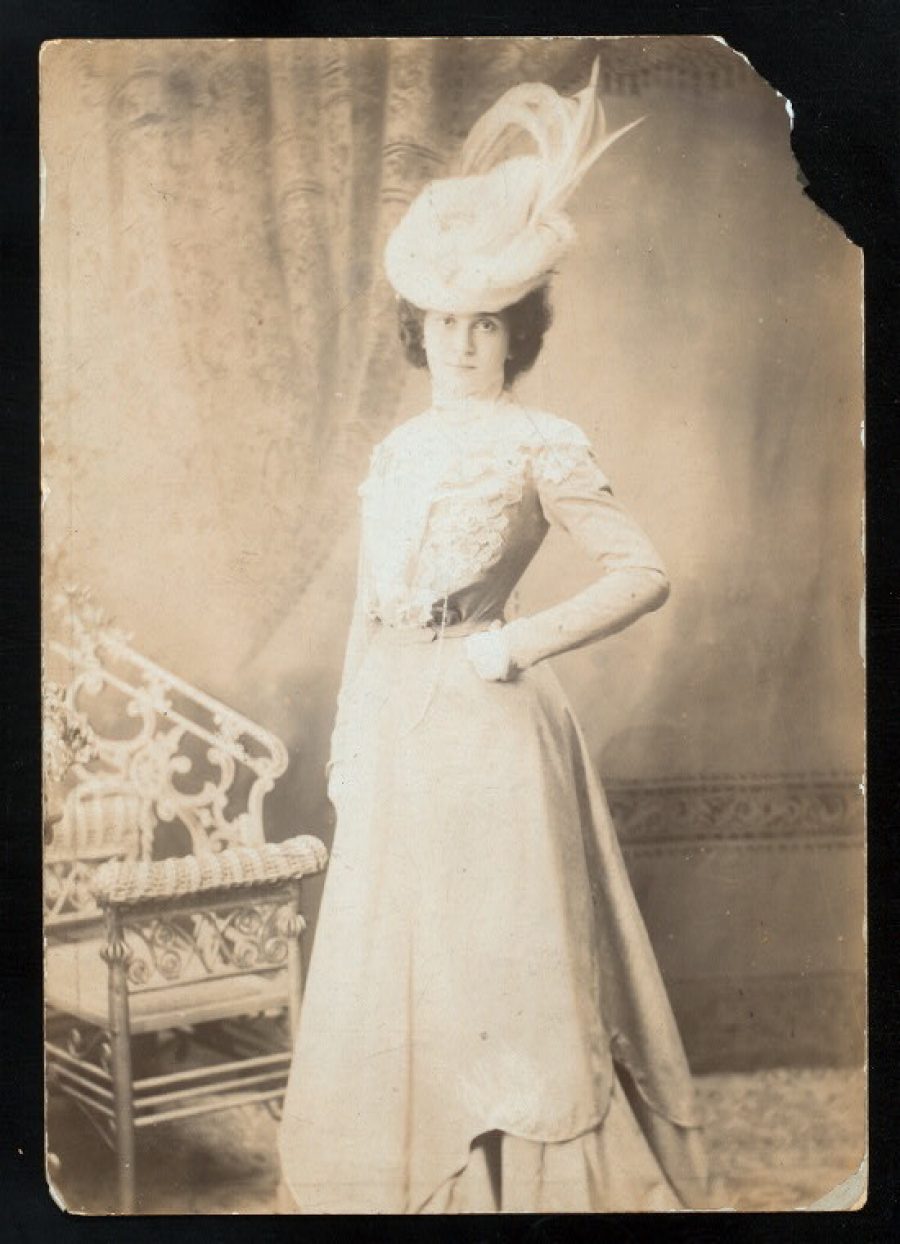

Bertha Kalich, Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library.

“A day that tortured my body and tormented my soul”: Bertha Kalich’s Kol Nidre in Bucharest

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

Bertha Kalich (1874-1939) was a great actress on the Yiddish and English-language stage. Born in Lviv, Ukraine, she was a prima donna in Gimpel’s Theatre and throughout Europe before coming to America. “Mayn leben” [My life], her serialized memoirs (written with Tsvi-Hirsh Rubinshteyn), were published in the New York Yiddish daily, Der Tog, from March 7-November 14, 1925. The following extract, “Uphill!”, was published on July 11, 1925. It describes Kalich’s experience in the early 1890’s in Bucharest, when her actor colleague Mordkhe Segalesko 1 asked her to sing with him for Yom Kippur services.

A fresh, angry, autumnal wind let loose in a wild dance over the streets of Bucharest. Every little leaf, every speck of dust, was lifted by the wind and spun and carried far, far away with a dry, easy whistle.

Bertha Kalich, Billy Rose Theatre Collection, New York Public Library.

Bucharest, the happy and cheerful city, suddenly acquired a different face. Some sort of strange, oppressive sadness filled every corner and disturbed the calm. It seemed to me that my heart was struggling. And I felt that soon, soon, something would happen that would shake up my whole being and I would become another person. Minute by minute, I had the feeling that any second now, a large cloud would come tearing down out of the sky and annihilate this puny little world of ours, which was full of so much evil and foolishness.

One thought revolved in my mind: The Day of Judgment is coming!

I had never before thought of Yom Kippur with such a feeling of fear. In my imagination, I painted a picture of how God, as if were possible, sat there in his heavenly tents enveloped in flames, waiting for the day when He would, in His great mercy, judge His people. And tomorrow is the day! Tomorrow, the children of the People of Israel will go to synagogue and there confess before the Creator. Tomorrow it will be decided who will live, and who, God forbid, will not; who will be killed by fire and who by water, and who by a plague… Tomorrow is the day of judgment, the Yom ha-din…

And here one sees how Jews in the streets prepare themselves for the great day. Good and pious, they forgive one another the wrongs they have committed against each other. One wants to come to God pure, and one hopes for forgiveness.

I will never forget this Yom Kippur Eve in Bucharest. It was a difficult day that tortured my body and tormented my soul. I suddenly felt the great responsibility that had fallen upon me. That evening and the following morning I had to sing in the synagogue and I had to send a prayer for my brothers who soaked themselves in tears and worry, to purify their hearts and plead for another year of life.

At dusk, when the candles twinkled here and there from Jewish windows, I was ready to go to the synagogue. Dressed in a white satin dress and a white hat, accompanied by my husband, I set out in the direction of the theatre, which had been arranged to serve as a synagogue. 2

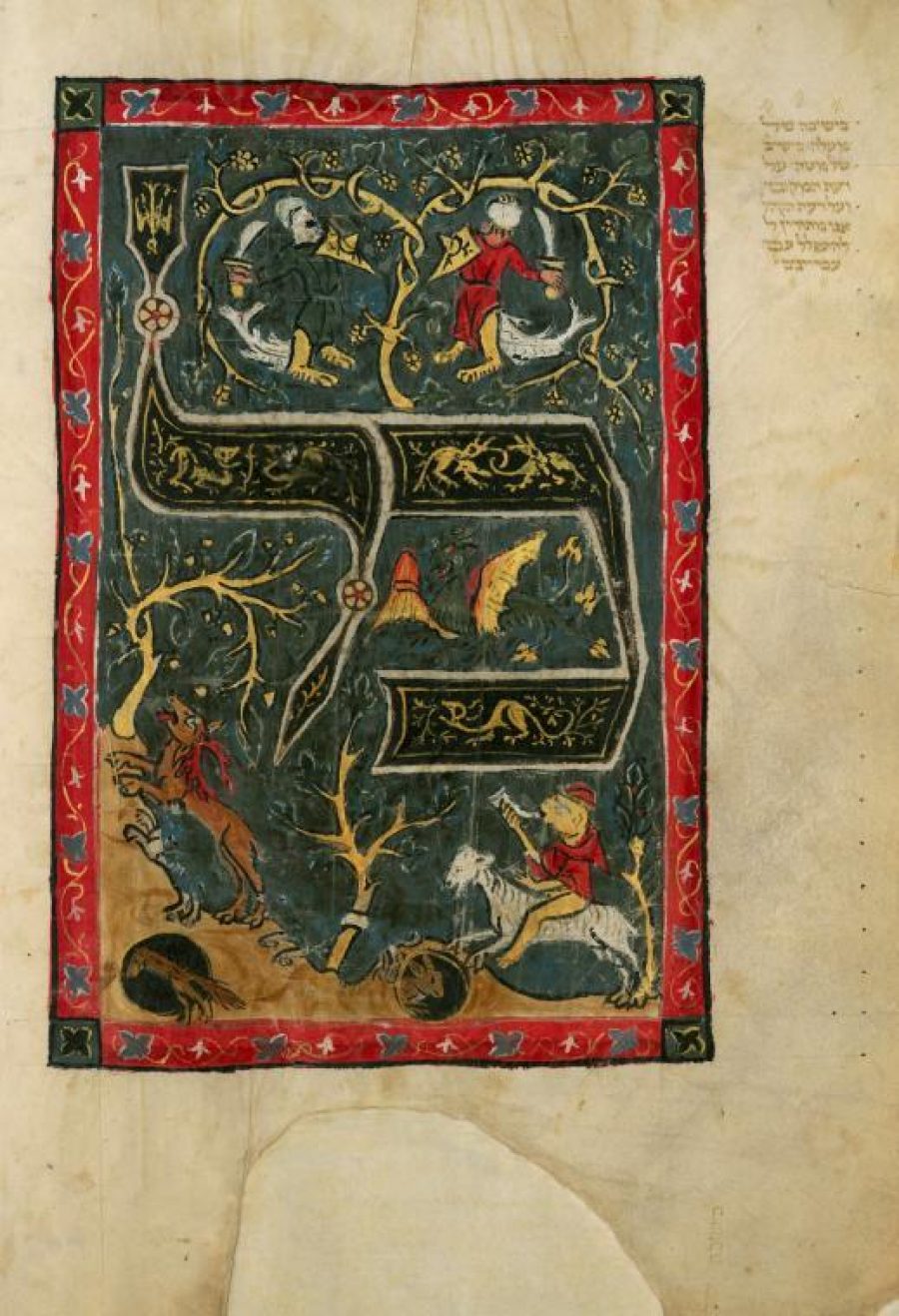

Kol Nidre, Image by David bar Pesah, Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library.

Outside, it smelled of deep autumn; the air was cool but pleasant, and the angry wind of the morning had vanished. In the sky, the iron-gray clouds sketched various shapes. Over there it seemed that a flock of sheep knelt before some sort of tall, gruesome figure, and here it seemed that a host of children danced in a circle, like a polonaise that was quiet and calm…

I entered the synagogue through a side door. My place was behind a curtain, so that no one could see me. I could see everyone. I stood as though rooted to the spot and observed the tall, waxen candles that had just been lit for the souls of the deceased. I observed the people who came a little bit earlier, in order to fit in another prayer, before rising for the Kol Nidre prayer. People cried their hearts out and it became easier for them…

I saw Segalesko, sitting in a front row with a tallis over his head, looking into a High Holiday prayer book. In here, he looked like a completely different Segalesko to me. Suddenly, the singer of doinas vanished and before me appeared a Jew who was God-fearing and holy. From his eyes a deep sorrow looked out, and he seemed to be preparing to fulfill a great mission in life…

The crowd grew even denser in the synagogue. People took their places in the rows, everyone in an assigned seat. Their heads covered in white taleysim edged with embroidery, they created a strange picture. The silver glimmered in the candlelight and their heads shook to and fro, right and left — a swell of waves in a silver sea, flowing among waxen candles… Suddenly—

Someone rapped a hand on the synagogue platform. It became quiet in the long and wide hall — but it was a tense silence. From the side, a man sighed out a deep “oy” and it became quiet again.

From the lectern, a weeping; a rich, refined voice burst into song. Notes rose and fell. Here the voice bell-like, there moaning like a small, sick child. The voice went quietly and sweetly from low to high—first pleading — then reproaching. Here the voice trembled and there it beat with steely determination; here it was weak and there it commanded — and these two words rang out: Kol Nidre.

The audience heaved a sigh. And the choir answered with a resounding swell as wide as the sea and as strong as stone. The whole hall was filled with song, and it seemed that one had suddenly overcome a difficult passage on the road and freed oneself from a heavy burden. Segalesko the cantor was much greater than Segalesko the actor. Everyone marveled at him and he was worthy of the astonishment.

When it came to the “Ya’aleh,” only then did Segalesko show what he was capable of. The audience listened raptly. And on the third “ya’aleh” came the big surprise. I received the signal from behind the curtain and to the accompaniment of an organ, I began to sing a solo.

I was never so excited in my life as in that moment, when I began to sing the “ya’aleh.” I became completely disconcerted and it seems I did not hear what I was singing. But when I finished, those close to me told me how wonderfully I had sung.

Royal Palace, Bucharest. Image from George Arents Collection, New York Public Library.

On the second day at the Yom Kippur Musaf service, I sang another solo: Ha-ben Yakir Li Efraim, but there I was more courageous, and it was no less successful than Kol Nidre. My voice was like a good wine; it became stronger and bolder, and the congregation enjoyed it greatly.

In spite of the fact that I was quite weakened from fasting, I did not follow the advice of my husband and my friends to break the fast. Several of them even tried to convince me that a pregnant woman is not allowed to fast at all, but I did not obey them and I kept the fast until after ne’ilah.

And in honor of my fasting, my wish was fulfilled that my second child was a boy….

The dear, good reader might not be able to imagine that the “Ya’aleh” that I sang in that Kol Nidre evening took me as far as the Romanian National Theatre 3 and yet — that’s how it was.

The organist that Segalesko had engaged from that theatre fell so deeply in love with my “Ya’aleh” that he began working with his people in the theatre that they should come and hear me sing. The organist, together with a certain Dovid Hirsh, 4 who was the choir director in the Romanian Theatre (today a director of a Yiddish theatre in Chicago), did all they could, and their one mission was to see me on the stage of the National Theatre in Bucharest.

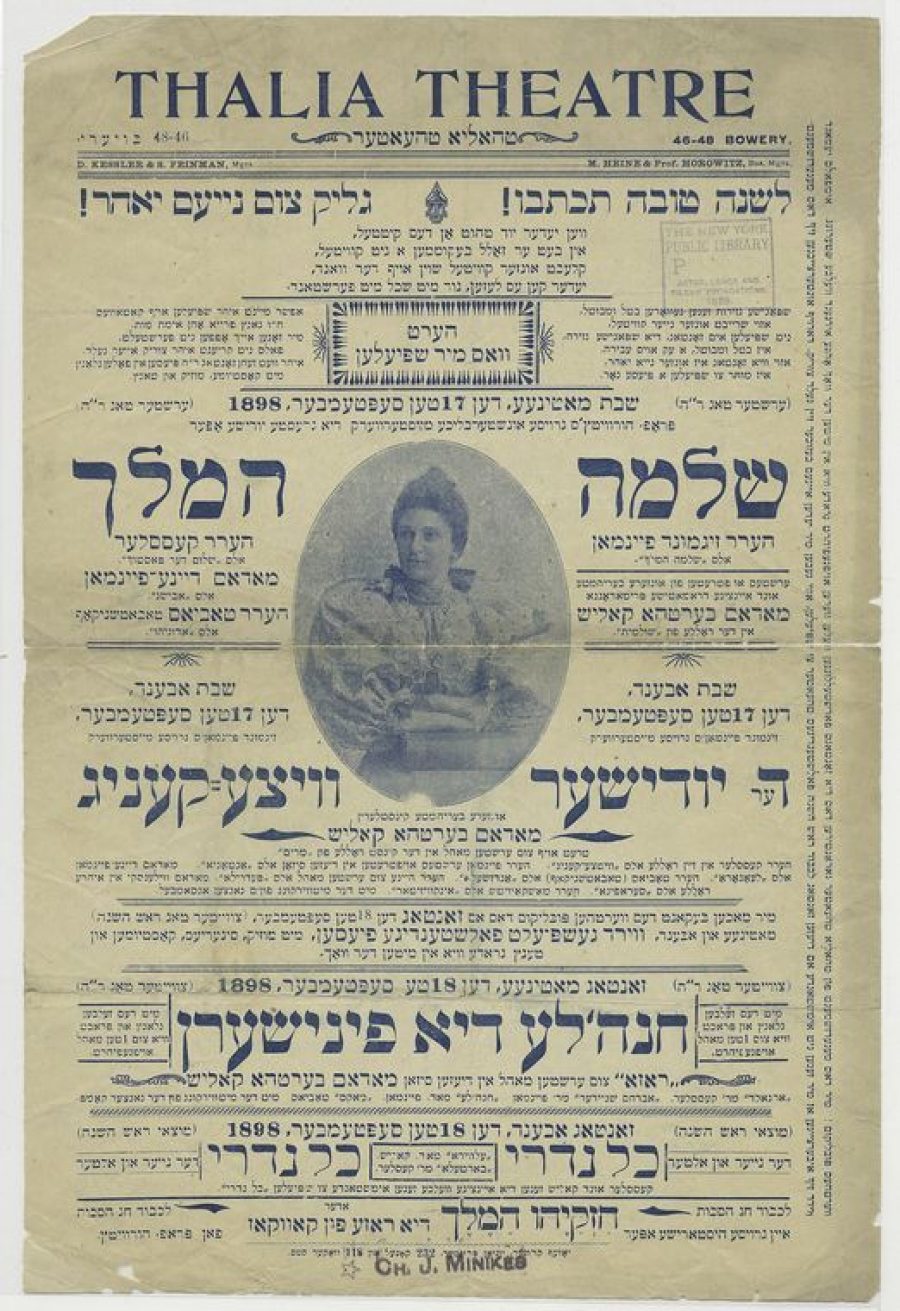

Shelomoh ha-melekh [Shloyme ha-meylekh]. Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library.

Bertha Kalich (pictured) later starred with David Kessler in the play Kol Nidre, by A. Sharkansky, at the Thalia Theatre in New York in 1898.

Great was their effort, but it was not realized so quickly. I was a Jewish woman, and they [the National Theatre’s administration] did not want to grant me such an honor, to sing for the king, for his family, and for the great people of the city. No Jew had even been able to or been allowed to grace the stage of the National Theatre before. Too strong was the anti-semitism, too strong was the hatred for the Jewish name. Too little respect was had for the Jewish artist.

Still, I did perform in the National Theatre in Bucharest. That was months later — but about that I will speak later.

Translated and notated by Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel.

© The New York Public Library

Notes

-

1Mordkhe Segalesko (Segal) was a leading Romanian Yiddish actor, together with his wife, Amalia. Bertha Kalich describes him a star who was more successful with his outward presentation than with his talent, and a better cantor than an actor: a strange-looking, neckless man who went about in unbuttoned shirts and slippers, plump and panting, with a hoarse voice and hearty laugh. He was successful in comic and tragic roles, and well-loved in Bucharest. His wife Amalia was more than six feet tall: a tough, vulgar-talking, chain-smoking actress who was extremely generous and protective of actresses and choristers. Her nickname for Kalich was the “Purim-a donna.”

-

2The Yom Kippur services were organized and led by Segalesko, who had rented a theatre to serve as a synagogue for the High Holidays, a not-uncommon practice in eastern Europe and even in the United States. There is no information about what type of service it was, but the use of an organ, an instrument re-introduced to religious services by Reform Judaism in the 19th century, and the performance by Kalich herself suggests that this was more modern than traditional service. Her text does not indicate if she remained behind the curtain while singing, or emerged, or what function the curtain served beyond keeping her out of sight until her solo. Though a professional actress and singer, she was raised in an Orthodox environment which traditionally prohibits women from singing publicly (kol isha). Religion, haskole (enlightenment) and gender in the Yiddish theater are important topics for future research and discussion.

-

3Bertha Kalich became the first Jewish person to sing in the Romanian National Theatre, overcoming a long historical tradition of anti-semitism.

-

4Dovid Hirsh, b. 1870, studied synagogue and vocal music and worked as a music director and composer for the Yiddish stage, with playwrights Avrom Goldfaden, Joseph Lateiner, and Moyshe Hurwitz, among others. He also worked as a choir director and soloist in the Romanian National Theatre, where he was successful in arranging Bertha Kalich’s performance.