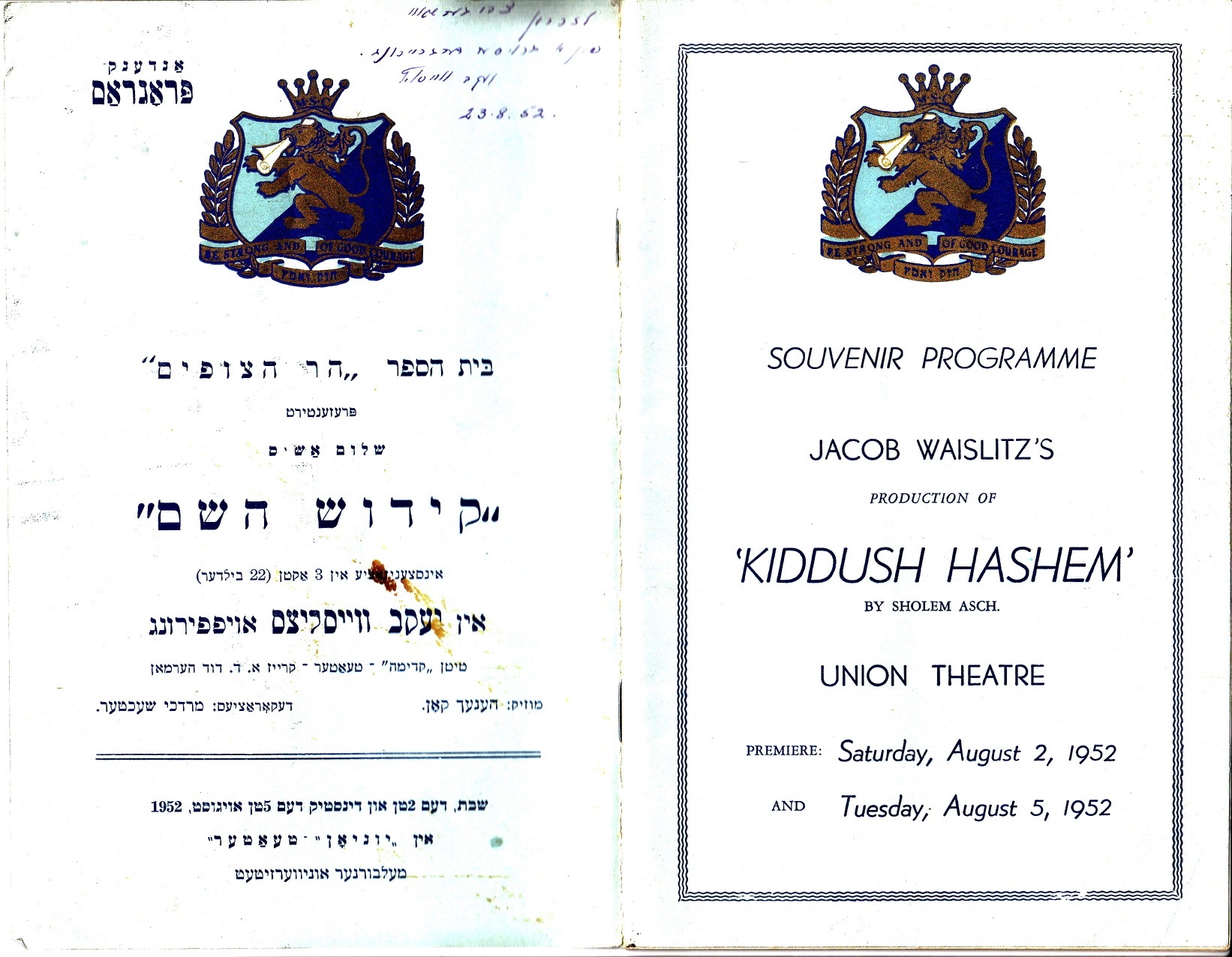

David Herman Theatre, Kiddush Hashem, 1952. Image courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, "Yiddish Theatre in Australia 1908 to 2015," http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archives.

Sholem Asch at the End of the World

Katarzyna Kwapisz Williams

Sholem Asch belongs to those Yiddish authors who often defy rather than obey the conventions of Yiddish culture and Jewish sensibilities. Yet, his works have traveled the world, following Jewish immigrants and spreading the Yiddish culture, blending it with local concerns and interests. They traveled as far as Australia, where many Jewish immigrants found their home. The production and reception of his works in Australia can serve as a prism through which we can better understand the Australian Yiddish stage. For the most part, records related to Sholem Asch’s presence in Australia are found in the Australian Jewish press, and focus on the acquisition of his works by local Jewish communities, meetings of literary groups, or reviews of his books. From these snippets of information one may gather that Asch’s Australian presence was more literary–read, recited, and discussed–than staged. Indeed, there are not many records of theatrical productions of his works, although it is clear from various accounts that Asch was a significant part of the story of Yiddish theatre in Australia.

From the outset, Jewish immigrants to Australia knew they would not be going back “home,” especially those fleeing the rise of Nazism, and, later, those who survived the Holocaust. These immigrants were determined to build new lives in Australia, in spite of the anti-refugee sentiments and antisemitic attitudes, which were common at the time. They spoke Yiddish, Polish, German, and Hungarian, and they brought with them culture in these languages, such as poems, songs and recipes, as well as the desire to recreate fragments of their old worlds in their new home. Yiddish journals published regularly by most synagogues and Jewish societies, newspapers and literary magazines, theatres, restaurants, and schools helped establish Yiddish culture in Australia, particularly in Melbourne.

While the Yiddish theatre has always been a family affair and a people’s theatre–with audiences tending to favor such genres as melodrama and musical comedy–more prestigious works, including Jewish classics, were indispensable to fulfill the theatre’s mission as a cornerstone of Yiddish culture and an essential element of Jewish life in Australia. This felt particularly important “in that little shtetl in ek velt”–a shtetl at the end of the world, as the members of the Jewish community in Melbourne called their suburb, Carlton. 1 In fact, it must have been the expectation that the ambitious repertoire, which included the works of Asch as well as Levinson, Jacob Gordin, Dovid Pinski, Sholem Aleichem, I.L. Peretz, and S. An-sky, would have been able to both recreate the world left behind, and express new perspectives.

It was within this rich cultural, Australian Jewish life that Asch’s works featured regularly. In 1937, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that Sydney’s Jewish Youth Theatre League was meeting to discuss and read Asch’s short stories, and described Asch as one of the great contemporary Jewish artists. In 1950, the South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus advertised The Apostle, “a ‘magnificent’ novel” that was, noted the ad, available for sale by local news agents. In 1952, The Hebrew Standard of Australasia announced a symposium by the Jewish Library Association revolving around a discussion of Asch’s latest book, Moses. The examples are numerous and point to Asch’s Australian literary presence. His theatrical contributions seem to be missing and this lack of coverage occludes what seems to be a rich presence of Asch’s theatrical works in Australia.

Front cover of Arnold Zable’s Wanderers and Dreamers: Tales of the David Herman Theatre (South Melbourne: Hyland House, 1998). This is a bilingual English/Yiddish book. The English reads from one cover and the Yiddish from the other cover. The Yiddish section was written by Moshe Ajzenbud.

Yiddish theatre in Australia dates back to the start of the twentieth century, when amateur Yiddish actors–“wanderers and itinerants, troubadours and minstrels” as Arnold Zable calls them–first arrived. Among them were Chaim Reinholtz, who arrived in about 1892, Samuel Weisberg (1908), his brother in-law Reuben Finkelstein (1911), and David Reizin (1912). They formed a Yiddish theatre club and then a troupe that performed at Melbourne’s Kadimah. With new Jewish immigrants arriving from Poland in the 1920s came professional actors such as Jacob (Yankev) Ginter, later dubbed by his colleagues “the pioneer of a high quality Yiddish theatre in Australia.” Post-World-War-II Yiddish-speaking immigrants further developed Australian Yiddish theatre and culture, with Melbourne becoming, as Freydi Mrocki observed, “the jewel in the Yiddish world’s crown.” 2

In Melbourne, Ginter joined Mordechai Schechter, an actor from Chełm who ran the Kadimah drama group and staged a variety of works adapted from Yiddish literature. In 1927, Ginter established the Di yidishe bine in Melbourne, which was later named after the renowned Polish-Jewish director, David Herman. Ginter, who, according to Zable, “insisted on producing classics,” started with Sholem Aleichem and Jacob Gordin, and staged over thirty plays from the literary Yiddish repertoire.

In 1929, Ginter produced Sholem Asch’s Undzer gloybn (Our Belief, 1914), collecting money for Yiddish day‐schools in Poland. Five years later, in collaboration with the local writer Pinchas Goldhar, Ginter staged an adaptation of Asch’s novel about immigrant life, Onkl mozes (Uncle Moses, 1918). Not only was it “the first original Yiddish theatre script penned in Australia,” as Zable points out, but it was a story that provided immigrants with “insights into their new way of life.”

In 1935, Ginter directed Asch’s Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance, 1907), and was joined a year later by his brother, the professional actor Nathan Ginter, who directed Motke ganev (Motke the Thief, 1917). The Oystralish-yidisher almanakh (Australian Yiddish Almanac, 1937), records Nathan Ginter’s staging Asch together with two or three other productions in 1936. However, the available review of his Motke ganev comes from 1941, when he directed the work and produced it with Rokhl Holzer and Jacob (Yankev) Waislitz. The reviewer, George Tryster (The Australian Jewish News), focused mostly on the plot and did not say much about the production, except for praising the excellent acting of Mr. and Mrs. Ginter and Miss Levita.

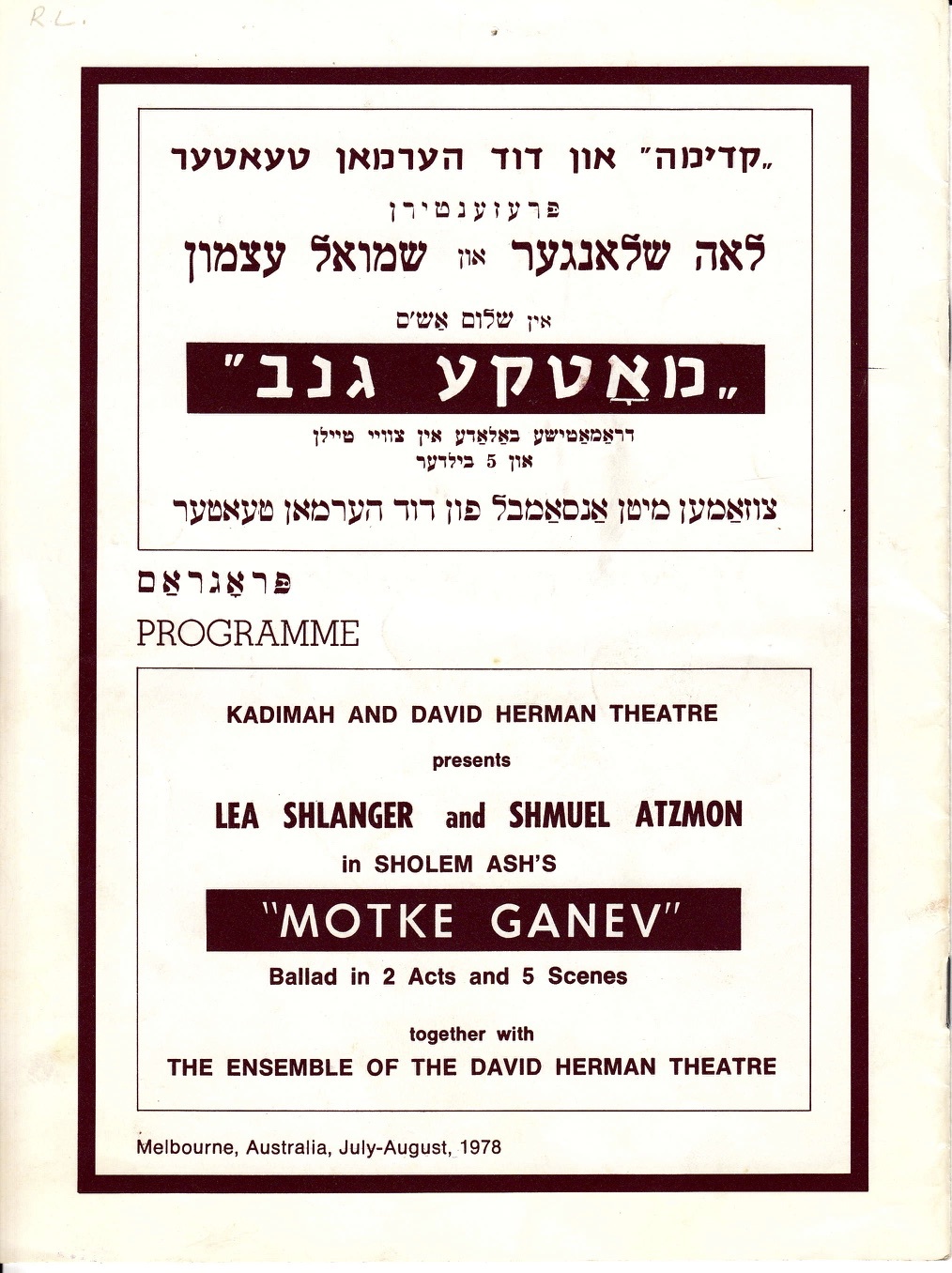

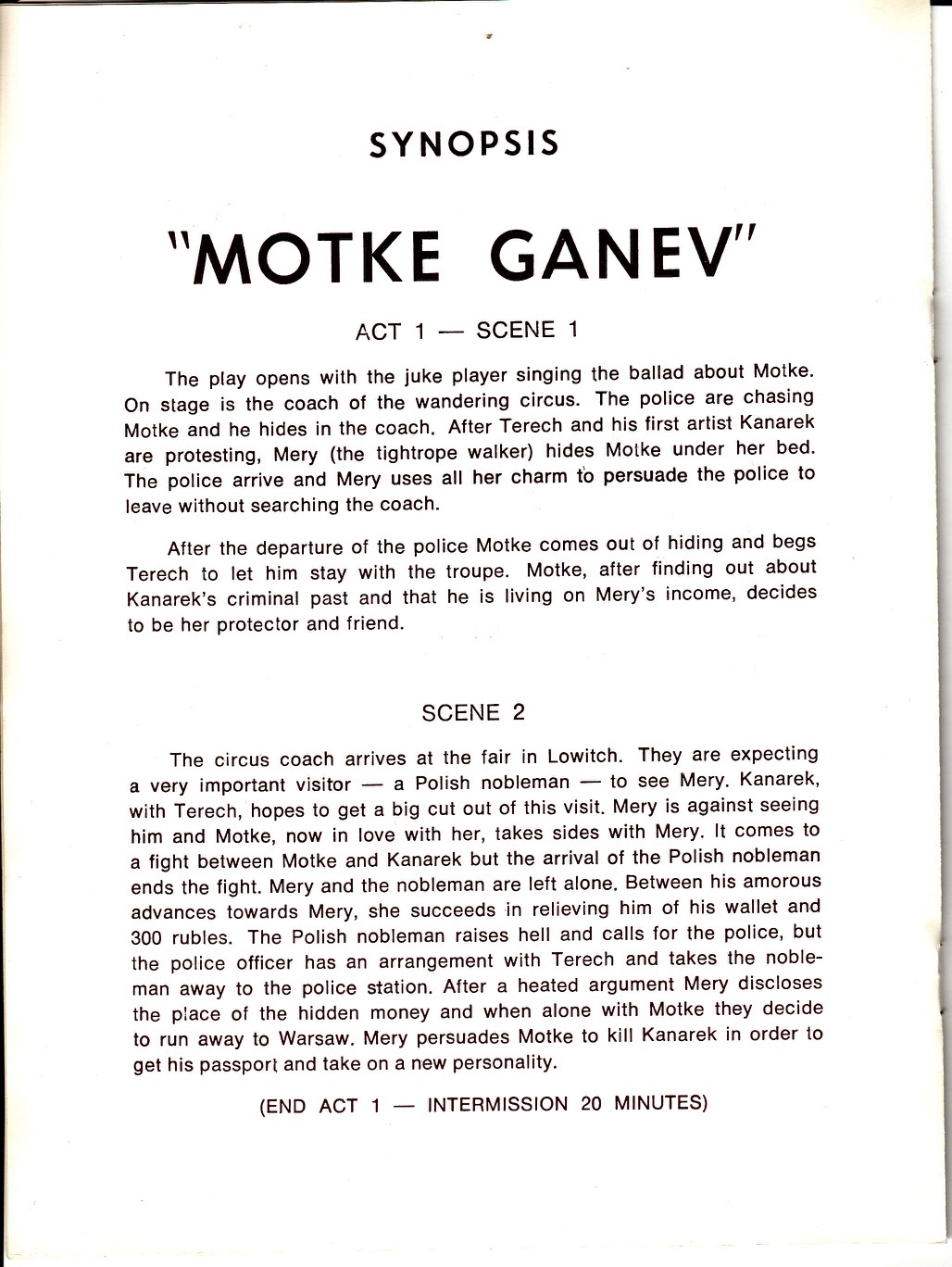

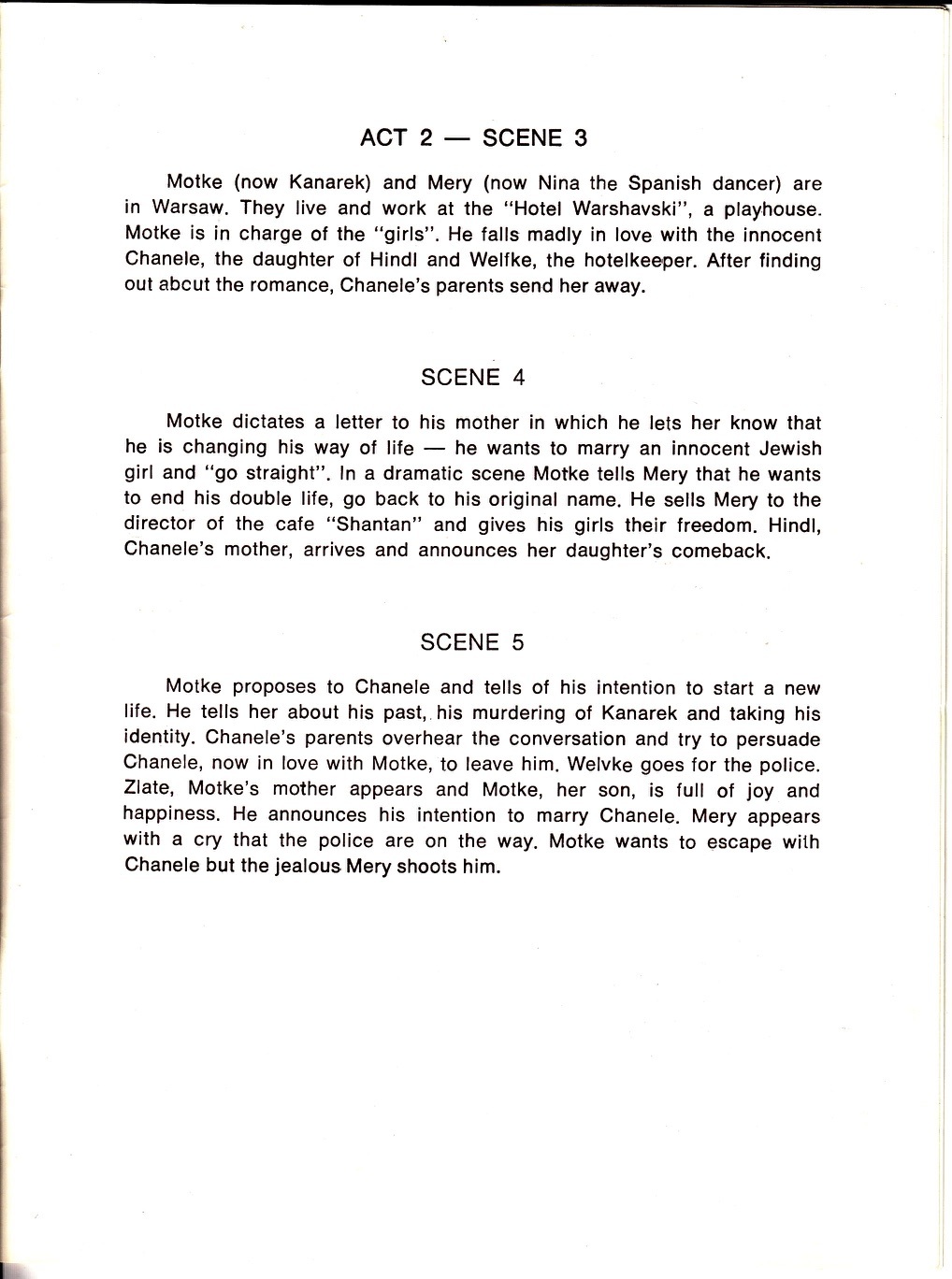

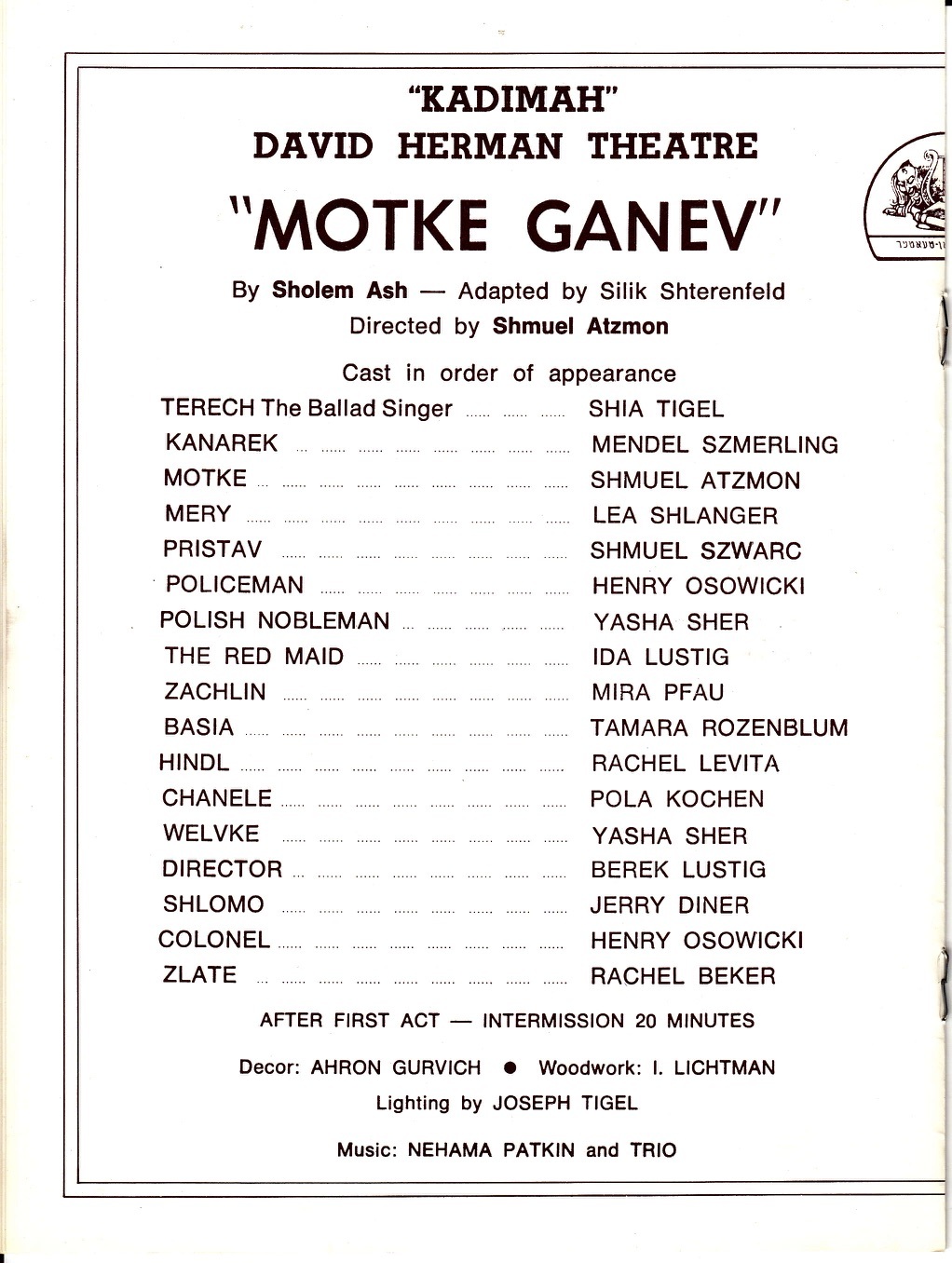

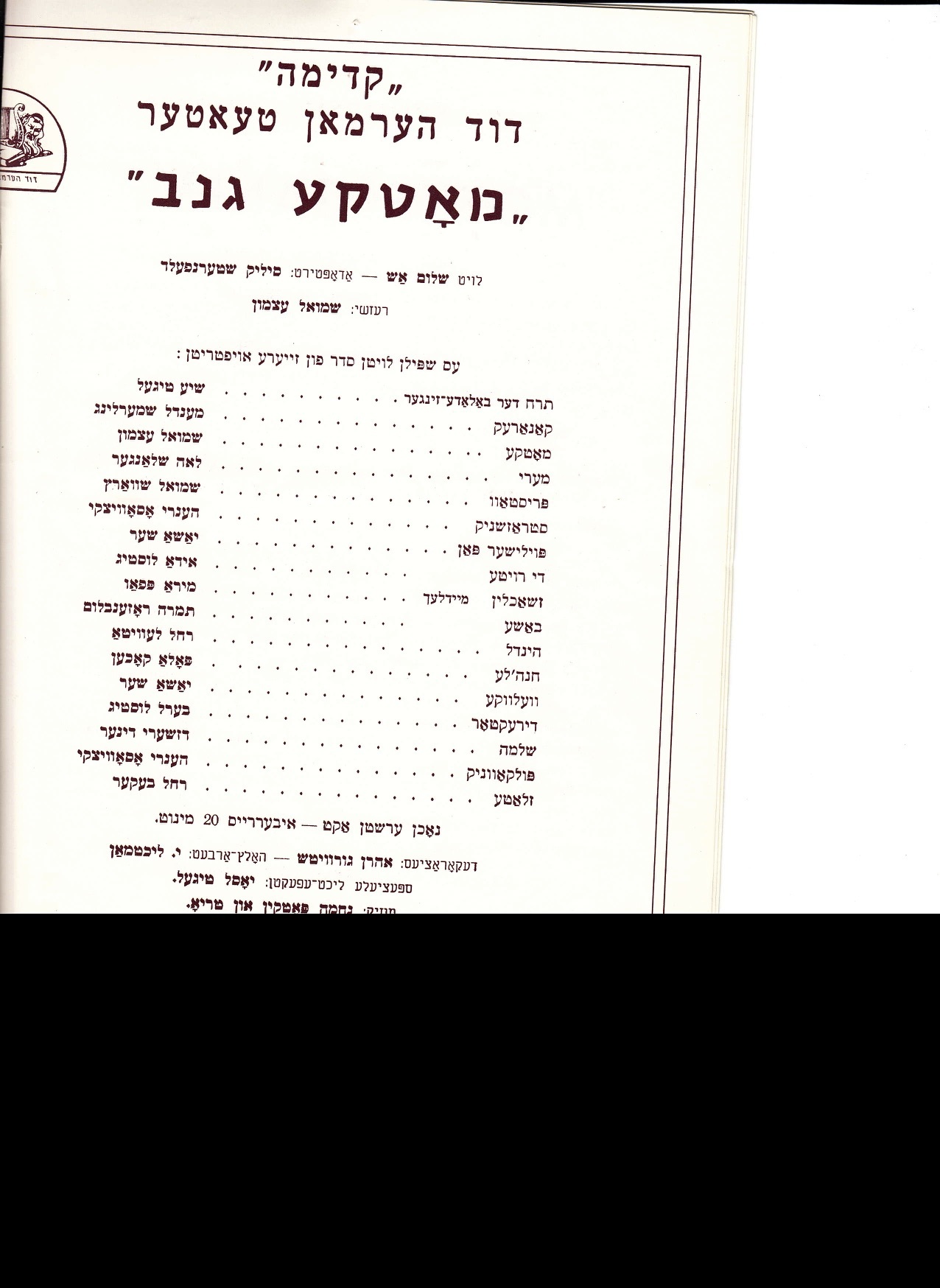

Program of the David Herman Theatre production of Motke ganev, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Center and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archive.

Program of the David Herman Theatre production of Motke Ganev, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Center and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archive.

Program of the David Herman Theatre production of Motke Ganev, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Center and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archive.

Program of the David Herman Theatre production of Motke Ganev, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Center and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archive.

Program of the David Herman Theatre production of Motke Ganev, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Center and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archive.

Also in 1936, Israel Rothman produced Asch’s Mitn shtrom (With the Stream, 1904) with the Kadimah drama group, and staged the same play in Sydney, between 1930 and 1932 on the invitation of the Jewish Club. Yet Rothman’s engagement with Asch in Australia started even earlier, most likely in 1928 in Brisbane. Rothman had come to Brisbane in 1924 and created a Yiddish amateur group and a literary circle. Asch’s work was featured both on stage and during the literary evenings. In 1928, Rothman staged Got fun nekome in Brisbane, to the outrage of the local community of Orthodox Jews. Zable adds that “[a]fter heated clashes the play went ahead, with a somewhat censored script.”

Rothman’s production was most likely not the first production of Asch in Brisbane. Serge Liberman writes of his works being staged in Brisbane sometime between 1914 and 1917 by the Yiddish Dramatic Circle. The success of the first performances of Yiddish drama, and “the encouraging response of the audience prompted the amateur actors to perform Asch’s With the Stream,” among others. 3

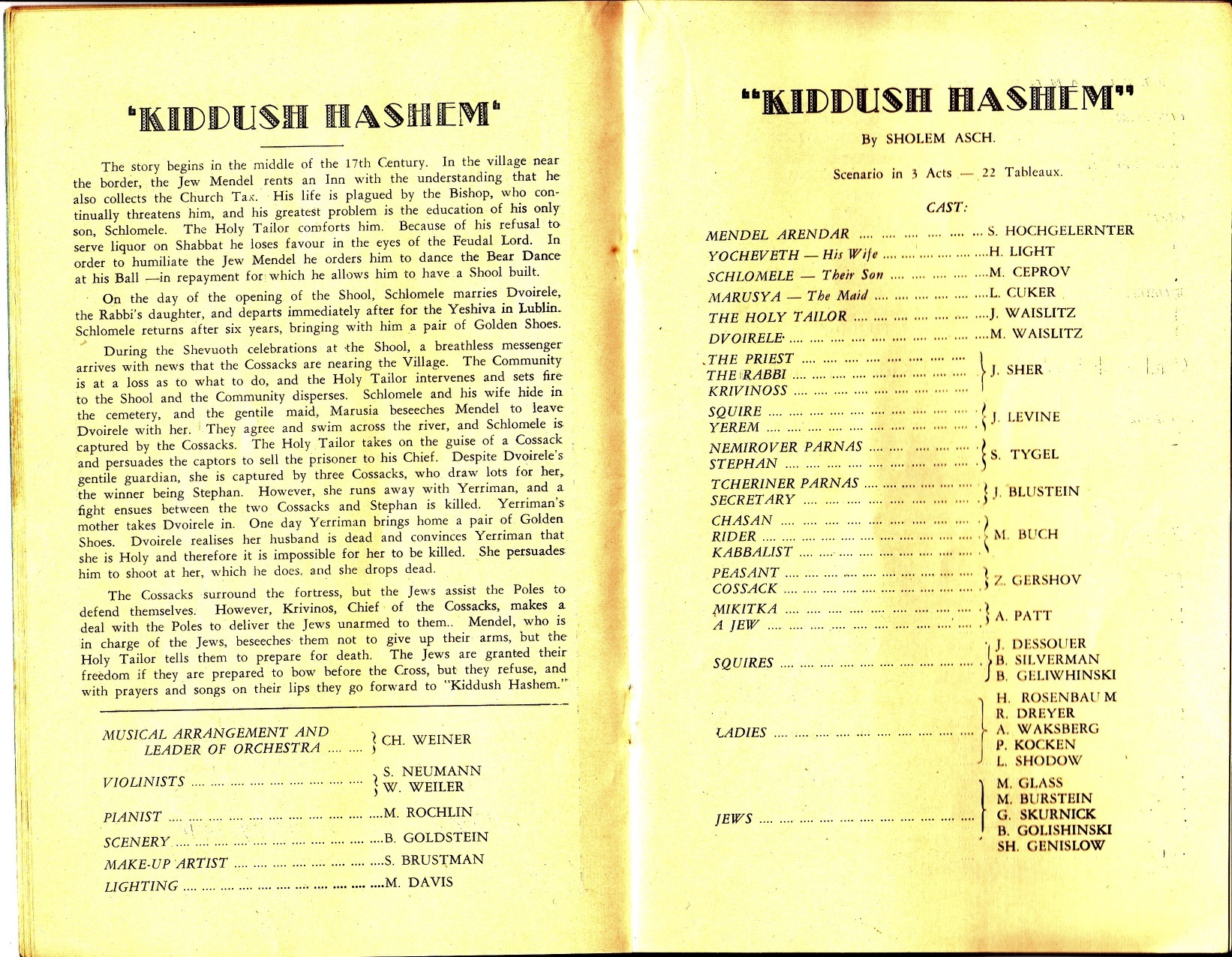

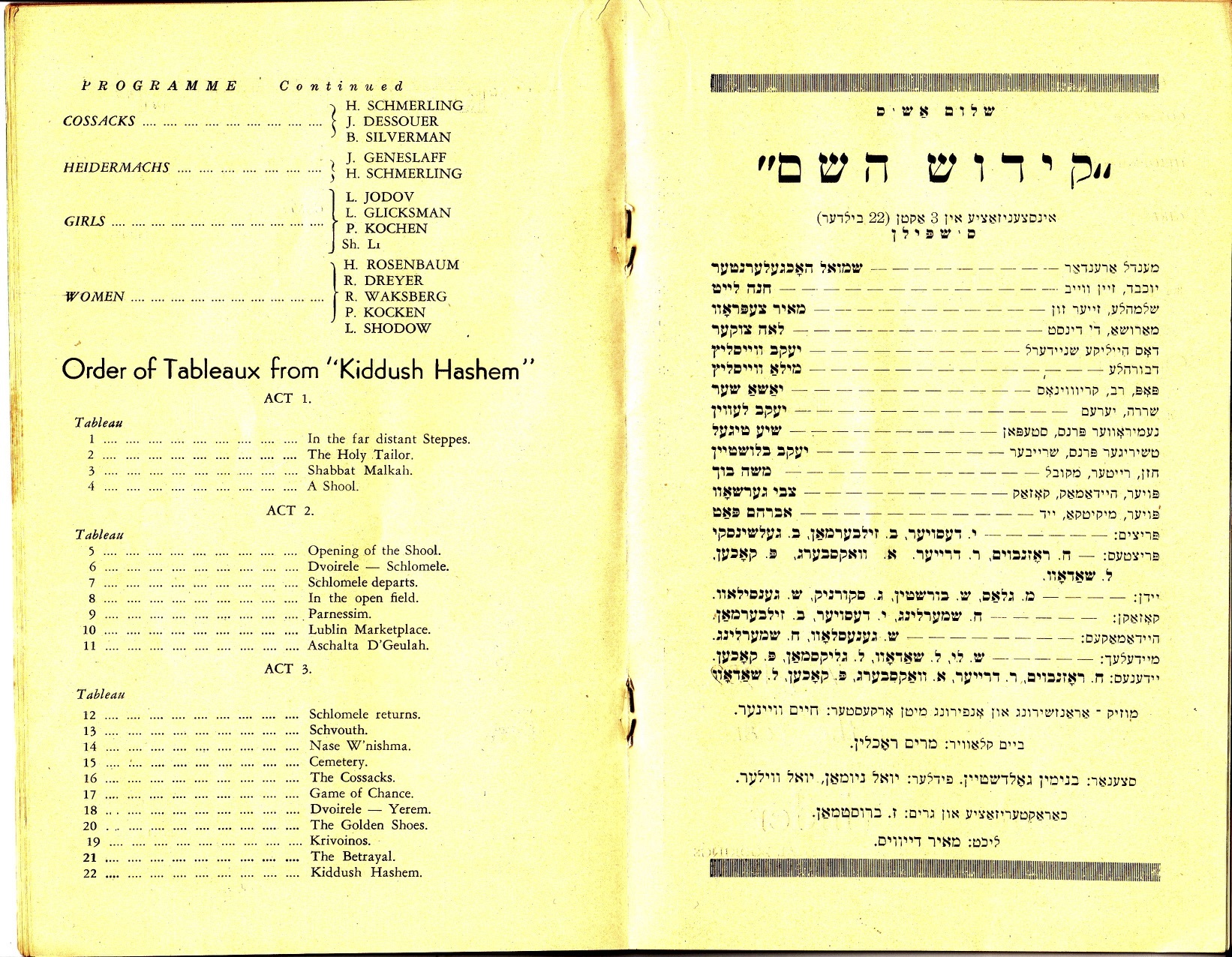

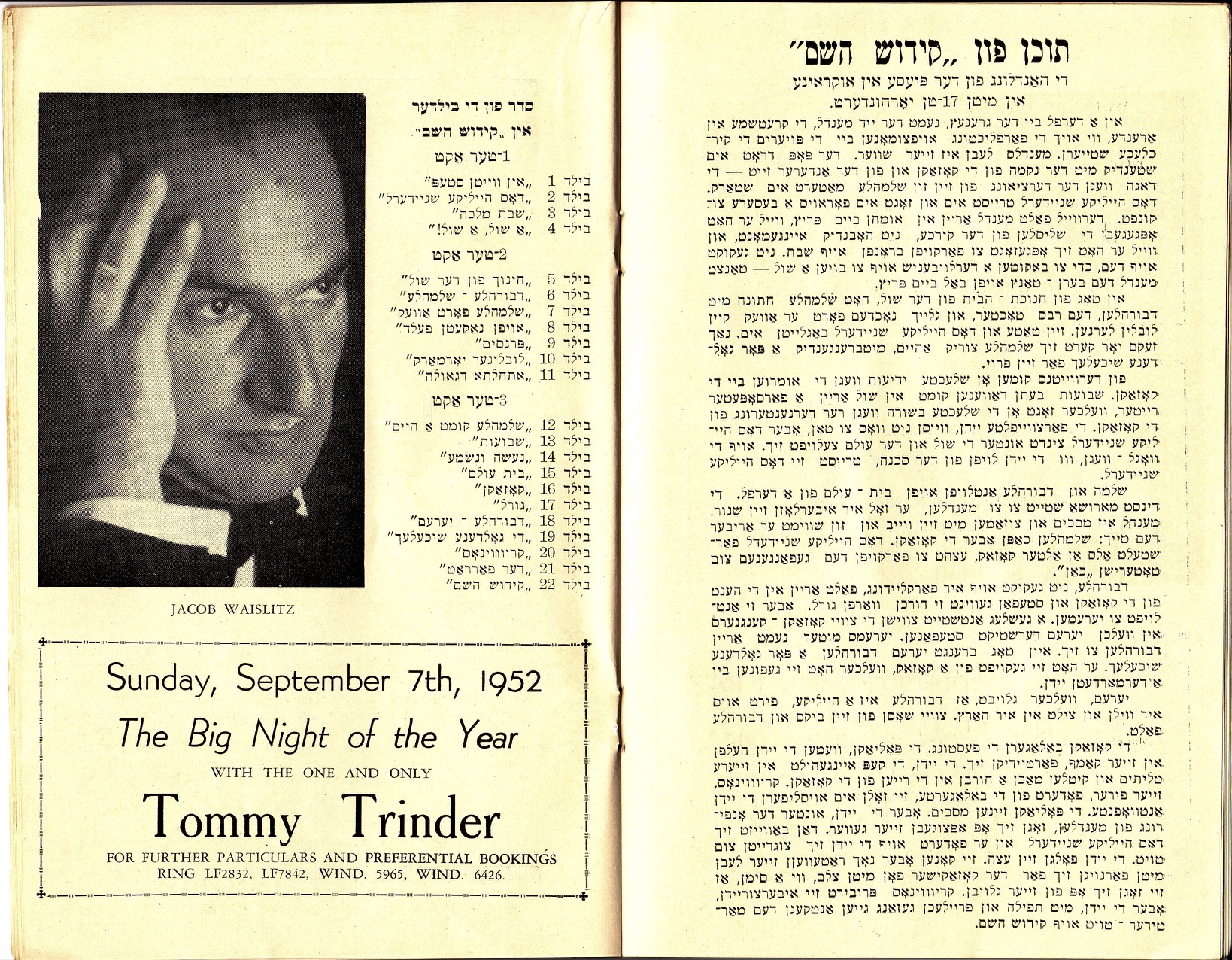

Program of the Union Theatre production of Kiddush hashem, 1952, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archives.

Program of the Union Theatre production of Kiddush hashem, 1952, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archives.

Program of the Union Theatre production of Kiddush hashem, 1952, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archives.

Program of the Union Theatre production of Kiddush hashem, 1952, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archives.

Program of the Union Theatre production of Kiddush hashem, 1952, courtesy of the Kadimah Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library, Kadimah David Herman Theatre and Events Programs, http://www.kadimah.org.au/Archives.

Nevertheless, Melbourne was unquestionably the center of fine Yiddish theatre. Since the 1950s, a variety of “vagabond stars” from Europe, the US, and Israel regularly toured Australia. In 1952, Jacob Waislitz produced at least two performances of Asch’s Kiddush hashem with the Union Theatre. With time, theatrical life started to rely on international actors and directors, many of whom traveled to Australia from Israel, and came with new ideas and repertoire as well as a willingness to stage classics, including Asch. In 1955, Zygmunt Turkow, a student of David Herman in Warsaw who immigrated to Israel 1952, adapted and staged Onkl mozes in Melbourne. The Australian Jewish News called the production “enjoyable and very well received by the large audience,” and praised the amateur actors Israel Rothman and Leah Zuker, who “rose ‘above the effect of acting’,” while others were criticized for their nasal intonation, wooden and stagey gestures, and “out-of-focus” characters.

In 1957 Shmuel Atzmon staged Motke ganev, and then performed and directed it again in 1978, together with Leah Shlanger. The latter production was reviewed by Leon Gettler in The Australian Jewish News, who described it as “a slice of Jewish folklore” in the form of a “stagey drama.” He criticized the production for coming close to “shallow melodrama” and that it required “some tightening-up if it should aspire beyond amateurish fumblings and artificiality.” Interestingly, Zable suggests reading this production of Motke ganev as “a parable of that fragile vocation called Yiddish Theatre.”

A declining number of Yiddish speakers in Australia and an increasing level of acculturation resulted in changes to the theatre. The David Herman Theatre continued its activities until the early 1990s. In the 1970s its successor, the Melbourne Yiddish Youth Theatre at the Kadimah, started producing new interpretations of the classics from the Yiddish theatrical repertoire as well as translations of English plays. Asch’s works, however, do not seem to feature as part of their repertoire. Particularly passionate about his works being recognized as a part of a great European literary tradition and translated into many languages, Asch might not have been disappointed by that. Rather, he would have most likely been contented that for so many Jewish immigrants recreating their life away from home, his works, like other productions of the Yiddish theatre, were, as Zable noted, “one reliable source of pleasure” in ek velt.

Note: I am very grateful to Arnold Zable for sharing his Yiddish theatre and Kadimah stories with me on one evening in the Brunetti Cafe in Carlton, Melbourne, and with the world by writing Wanderers and Dreamers: Tales of the David Herman Theatre (Melbourne, 1998) and other fascinating tales of Jewish life in Australia.

Notes

-

1Julie Meadows, ed., A shtetl in ek velt: A shtetl at the end of the world: 54 stories of growing up in Jewish Carlton, 1925-1945 (Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation, Monash University, Victoria, 2011).

-

2Danny Goes, “Yiddish with an Aussie accent,” The Australian Jewish News, April 6, 2011.

-

3Serge Liberman, “Yiddish theatre In Perth, Brisbane and Sydney,” Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal 9, part 1 (1981): 26-27.