A Tribute to Sonia Lizaron

Arnold Zable

Delivered at her funeral service, 26 August 2015.

Sonia Lizaron was a gracious, unassuming, unsung hero, and a wonderful friend. My wife Dora, my son Alexander, and I loved her. As did many others who came to know her.

She lived an epic life, but rarely spoke about it.

This tribute is based on some of the anecdotes and fragments Sonia recounted over the years, augmented by research from a growing body of sources. Sonia’s achievements are being re-discovered by researchers in Brazil, Germany, Israel, the USA, and France, some of whom I have corresponded with in recent years.

Sonia was born in Łódź on May 1, 1919. Her father, Aron Boczkowski, was an accountant in a textile factory. Both parents were active in the Jewish Labour Bund and possessed a deep love of Yiddish culture. Many years later, Sonia Boczkowska would adapt the names of her parents Lisa and Aron, and become known as Sonia Lizaron.

Sonia grew up in pre-war Łódź, a vibrant centre of Yiddish culture. She was brought up with the Bund ideals of Yiddishkayt, a secular humanism based on community service, a yearning for social justice, and pride in Yiddish language as the mother tongue, mame loshn.

She attended a Yiddish primary and high school and she trained with theatre director and writer Moyshe Broderson and his Łódź kleynkunst theatre, called Ararat. Kleynkunst is the art of Yiddish cabaret and Broderson was one of its leading exponents.

Sonia’s mother died of cancer before the war. Two photos of Lisa, one alone, and the other with her two young children, Sonia and Genek, were among the few photos Sonia displayed in her room in Gary Smorgan House, where she spent her final years.

Sonia was deported after the outbreak of war, with her father and brother, to the Będzin ghetto, located in Upper Silesia, territory annexed by the Germans. In 1942, a year of deportations, Sonia’s father and brother were herded with fellow inmates into a train bound for nearby Auschwitz.

Sonia told me this extraordinary tale. She went to the station to join her brother and father, despite the objections of Alfred Rossner, the wealthy German factory owner, and saviour of Jewish families, a Schindler-like character. Rossner came to the station, located her, knocked her out, and took her back to the factory. “He saved my life” Sonia said.

Sonia did not waste her reprieve. In the Będzin ghetto she performed as an actor in Sami Feder’s theatre and music ensemble, Muze, and appeared as a reciter of texts written by her friend Sophie Shpiglman who was later murdered in Auschwitz.

Sonia Lizaron and Sami Feder.

Born in 1909, Sami Feder was an accomplished director of Yiddish theatre, trained in Berlin and Poland. With the rise of Nazi Germany in the 1930s, he wrote and directed satires about Hitler as a warning of the perilous danger of Nazism. He was to play a big role in Sonia’s life.

Sonia recited texts about the suffering of her people in Będzin, but met with opposition from the ghetto Judenrat because they claimed such poems would have a negative influence. Characteristically, she wanted to mirror the realities of her people in her performances and reflect the truth. This was a vision she shared with Feder.

It is estimated that out of 30,000 inmates of Będzin ghetto only 2,000 survived. After the liquidation of the ghetto in 1943, Sonia was deported to the slave labour camp Annaberg, a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen, then to Mauthausen concentration camp, and finally to the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen. Even here, she sang for her fellow inmates.

Sonia was among the thousands of inmates liberated in Bergen-Belsen by British troops on April 15, 1945. When the British entered, they were shocked at the scenes that met them. Thousands of unburied, naked corpses lay scattered about the camp, men, women, and children shrunken to skin and bone, expiring of typhus, tuberculosis, and dysentery. Exhausted inmates, infested with lice and sores, lay on bare boards in filthy compounds, unable to move even at the sight of their liberators. Thirty thousand had died within reach of freedom. Fourteen thousand were to die in the first weeks after liberation.

Perhaps Sonia was among the women who raided the quarters where the SS women kept their makeup — and applied powder and lipstick to their emaciated faces in order to regain a sense of womanhood.

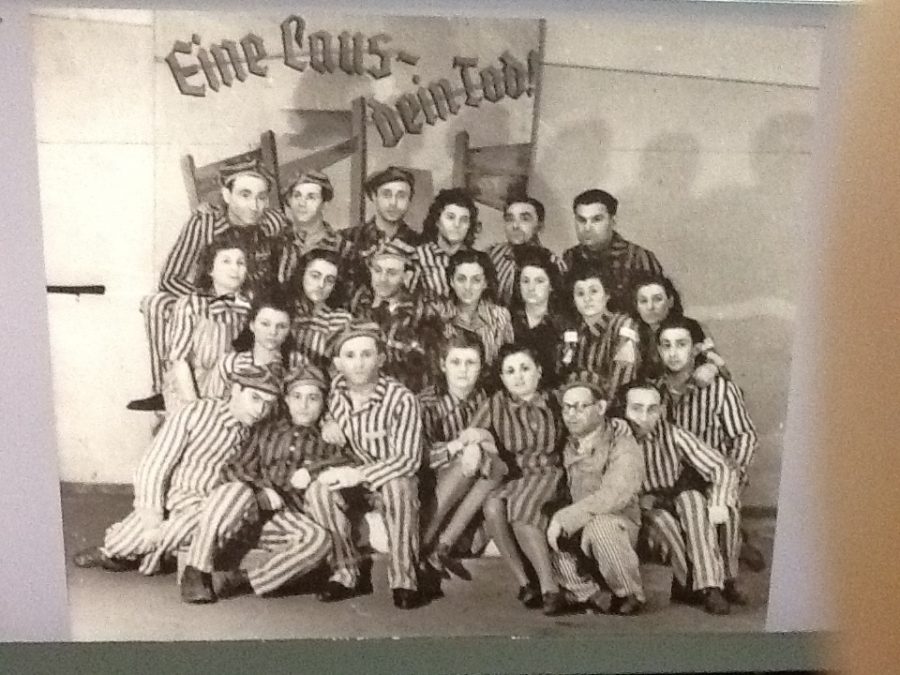

The Katzet Theatre in Bergen.

The British burnt Bergen Belsen, and set up a Displaced Persons (DP) camp in the former officer’s quarters, two kilometres away. Sonia was reunited with Sami Feder in Bergen-Belsen soon after liberation, and worked with him in the DP camp’s Jewish Central Committee. She co-founded the Katzet Concentration Camp theatre with Feder, and performed with the ensemble as a singer, reciter of poems, and lead actress. She told me she rode a bicycle round the camp in search of people with theatre skills who could join the troupe.

Sonia went from bed to bed in the camp’s hospital, collecting testimonies, poems, and songs from survivors, which were used in the writing of original texts performed by the theatre. She also helped retrieve Yiddish songs. She sang them so that they could be written down and adapted for performance. They were reproduced by Sami Feder in a book titled Zamlung fun katset un geto lider (An Anthology of Songs and Poems from the Ghettos and Concentration Camps), published in 1946.

The Katzet theatre’s first performance took place on September 10, 1945. Three thousand attended, in a hall that could accommodate only one thousand. Thinking a demonstration was under way, British offices called for tanks. Marian Zhid who attended the first performance, reported in the journal Freiheit:

They played it as written: with tears and blood, with… self-sacrifice and love. They had no need to play-act their roles; they had lived them in the reality of Nazi camps, ghettos, and forests, pursued like homeless dogs. This was a new universe, a new theatrical reality. They pulled me with them into a valley of tears, death, mud, and illness… and a minute later they lifted me up to their hopes and dreams. Never was there such art in the history of our theatre.

Sami Feder defined the Katzet theatre’s aesthetic as: “the art of the clenched fist,” and “frontline art,” an evolution of the Artform he had forged in the 1930s as Hitler rose to power, and as an inmate in the Będzin ghetto.

The ensemble rotated four shows: two evenings of kleynkunst, Yiddish cabaret, made up of poems, songs, and sketches written by Sami Feder and others, representing the recent horrors of camp life. They did not portray themselves as victims. The performers were not bowed by the experiences, and they did not shy away from representing their recent suffering. Their emphasis was on resistance and remembrance. They saw theatre as an act of emotional release for both performer and audience, a means of healing.

In one memorable photo we see Sonia reciting “Shikh fun maydanek” (Shoes from Majdanek) in stylized camp uniform, striped prison garb, a yellow Star of David pinned to her chest. She performed against a backdrop of a mountain of shoes, an embodiment of “frontline art.” The performances would end with the singing of Hirsh Glik’s Partisan’s hymn (Zog nit keynmol), perhaps the first time it was used to end memorial evenings.

The other two shows were Sami Feder’s adaptations of two classics of Yiddish theatre: Sholem Aleichem’s, 200,000, oder Dos groyse gevins (200,000, or The Jackpot), and Der farkishefter shnayder (The Bewitched Tailor).

In the summer of 1947, the Katzet theatre toured DP camps throughout Germany, Belgium, Sweden, and France. Wherever they performed, audiences who had recently emerged from their harrowing experiences greeted them with great emotion and gratitude.

After the tour, the theatre was disbanded, and Sonia settled with Sami Feder in Paris where she led a creative life. She came to know Edith Piaf, Jean-Paul Sartre, among others, and studied in the Sorbonne. And she performed with the Yidisher kunst teater (Yiddish Art Theatre, YKUT); Gerard Frydman, an actor with the troupe, describes the years following Liberation as “a period of euphoria for the Yiddish theatre.” There was a hunger to resume life, to create, and to retrieve the rich repertoire of Yiddish culture, and Sonia Lizaron was at the heart of it.

In 1950, Sonia joined composer Henekh Kon in a concert of Yiddish song, which they toured to France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Germany. The tour included a return to Bergen-Belsen, months before the DP camp was finally disbanded. Kon described Sonia’s voice as a “beautiful mezzo soprano.”

Album Cover, In Joy And Sorrow - 13 Yiddish Songs.

In 1962, Sonia and Sami Feder separated. Feder moved to Israel, while Sonia settled in New York. Sonia rarely spoke about this period of her life, though she hinted it was a difficult and challenging time. New York became Sonia’s new home. She continued her career as a singer of Yiddish song, performing all over the US and Canada and internationally, including occasional concerts in Melbourne. She also recorded 13 Yiddish songs: In umet un freyd (In Joy and Sorrow), backed by an Israeli orchestra conducted by Alexander Tarski.

The more I listen to the record, the more I am impressed by Sonia’s skill, her expressive voice, its range, and the intense drama she brings to the songs. Sonia lived her music, and the record includes some of the songs she performed for the Katzet theatre. Such as Gebertig’s, “Shloymele vest lakhn” (Shloymele, You Will Laugh) and “Eyns, tsvey, dray” (One, Two, Three), a song about life’s fluctuating fortunes.

But Sonia could not survive on her singing alone. She started a new career as a computer programmer at a time when computers were the size of a room. Sonia was over forty years old at the time, adjusting to a new language, a new home, and to new skills.

She also sought out ways to heal the memory of the war years. She spent months in an ashram in India, located sixty kilometres from Bombay, and credited meditation with helping her deal with the burden of the past. She was always an adventurer and independent spirit.

In the 1980s, Sonia began living with her childhood friend, Pinhas Wiener, in Elwood. She hadfirst met the Wiener brothers, Bono and Pinche, in the Bund primary school in Łódź. For a long while, Sonia kept her flat in New York and divided her time between Melbourne and New York, where she lived independently for up to 6 months of the year.

Slowly Sonia made the transition. She wound up her affairs in New York and began living permanently with Pinche in the bayside suburb of Elwood. She finally moved with him to the Gary Smorgan House as they both approached their nineties.

Over the past thirty years, Sonia has been a dear friend of Dora and me. She developed a special connection with Dora; they intuitively related to each other. She was Alexander’s surrogate grandmother, and Pinche his surrogate grandfather. Alexander loved the evenings spent in the Elwood house with Pinche and Sonia, the meals they cooked, Pinche’s impolite jokes, his politically incorrect and belligerent ways, and Sonia’s unconditional love. “He is adorable,” she would say. They marked Alexander’s growing height with a pencil on the kitchen door.

When Alexander developed an interest in klezmer music and the clarinet, Sonia insisted on buying him a good quality instrument. She came with me to the music store to choose it, and coincidentally the jazz musician, Adam Simmons, stepped in and agreed to come to our house that evening to show Alexander how to assemble the clarinet. Sonia also came over that night, and Adam became Alexander’s teacher. Sonia would ring and always leave the message: “Well, let’s hear some news.”

There is a deeper story to Sonia and who she was. In the past week, I have been thinking of her, re-reading the work that has been done on the Katzet theatre, discovering new stories, immersed in her music as I have driven around the city, and in the many memories I have of her.

Yes, Sonia was a deeply unassuming and modest woman. She never big-noted her achievements and rarely spoke of her extraordinary past, but having known her for thirty years, it becomes clear that she was a fiercely determined woman. She lived a creative and vibrant life in the face of a dominant male culture. This was so even within such progressive movements as the Bund. While she lived with powerful, loving, yet domineering men such as Sami Feder and Pinche Wiener, Sonia, in her own way, quietly held her own, maintaining a subtle independence.

Her independent spirit can be seen in many ways: in her lifelong practice of the craft of acting and singing; her extraordinary resilience in surviving the camps, with her integrity intact; in her performances in the hell of the ghettos and labour camps. In her creative life in Paris, and most strikingly in the new life she forged post-1962 in the US after she separated from her husband. She went out there on her own, and created an entirely new career.

She became well known and much loved in New York, where she befriended writers and activists, including the Nobel Prize winning Yiddish writer I. B. Singer. She told me that she had observed one of his methods of writing, in his New York apartment. She said he would randomly draw out characters from his filing system, and then bring them together in his stories.

Sonia lived in a fourth-floor walk-up apartment. Over the past week I have had a recurring image of her, climbing the four stories day after day, mornings, afternoons, and back into the city at night to perform, to meet friends, to go out to theatres and the cinema; Sonia going solo - finding her own way, through necessity. This is when she created her new identity as Sonia Lizaron, a statement of her independence, but also an expression of her deep love of her mamushka and tatushka.

Sonia was much loved in Melbourne by a circle of friends with whom she attended the theatre, concerts, and films. She continued to give concerts in the Kadimah, especially to the Wednesday club for the elderly. She also joined the group of volunteers restoring and cataloguing Yiddish books in the Kadimah library.

She was also much loved in her final years by the staff in the Gary Smorgan home, where she kept her own space, and attended concerts and functions where she sang along. And she had the devoted daily support of her dearest friend Sheila and her daughter Susan.

Sonia did not dwell upon the past, preferring to live in the moment: she would often put a halt to questions about the past by singing the opening lines of the song: “Vos geven iz geven, un iz nishto” — what was, once was, and is no more.

Despite her fading memory, she knew who we were till the end. She called me “Arele der narele” even a week before she died. When you asked her: How are you? She would invariably respond: “I’m hanging in there.”

Sonia hung in there even as she was no longer eating: Susan made a profound observation in the hours after her death, as we sat by her bedside. Sonia had been there before. Her body could cope with hunger and deprivation. She was reliving the memory of her survival in the camps, in Bergen Belsen. The memory was in her body.

Till the end, Sonia’s first love was song and poetry. She retained the lyrics of many songs in a range of languages: Russian, Polish, English, French, and, of course mame loshn. Yiddish. This is how we communicated best in the final years, through poetry and song. If you mentioned Paris she would sing a Parisian song. If you mentioned Piaf, it was “Je ne regrette rien.”

One poem in particular stands out. Whenever I quoted a line from it, Sonia would take it up and recite the entire poem by heart – “Eybik” by the Yiddish poet, H. Leivik. “Eternity”: a poem about endurance, overcoming suffering; about toughness, and fierce determination. In all the years we knew her, she never cried: the closest she came was a gesture with her closed hands, brushing the back of the knuckles across her closed eyes. The central line of “Eybik” encapsulates her spirit. “Ikh heyb zikh oyf vider, un shpan avek vayter”: I lift myself up again, and stride on further.

Sonia, we loved you. We will miss you. But we have the rich memories, and we have your beautiful, expressive voice.

We conclude with one of the songs. I just did not know which one to choose. Each one displays a different facet of Sonia’s repertoire, her skills, and the diversity of her voice. There are folk songs, traditional songs, love songs, humourous songs and several songs by the Mordechai Gebirtig, the folk artist who perished in the Kraków ghetto. I have settled on “Eynzam.” Solitude is the best translation, rather than loneliness, a poem by the great Yiddish troubadour, Itsik Manger.

I see Sonia whenever I hear those final lines: “Tu ikh on dem kapelush/ Un ikh loz zikh geyn/ Vu zhe geyt men shpet bay nakht/ Eyninker aleyn” — “I put on my hat/and go on my way/ where does one go late at night, in solitude, alone.”