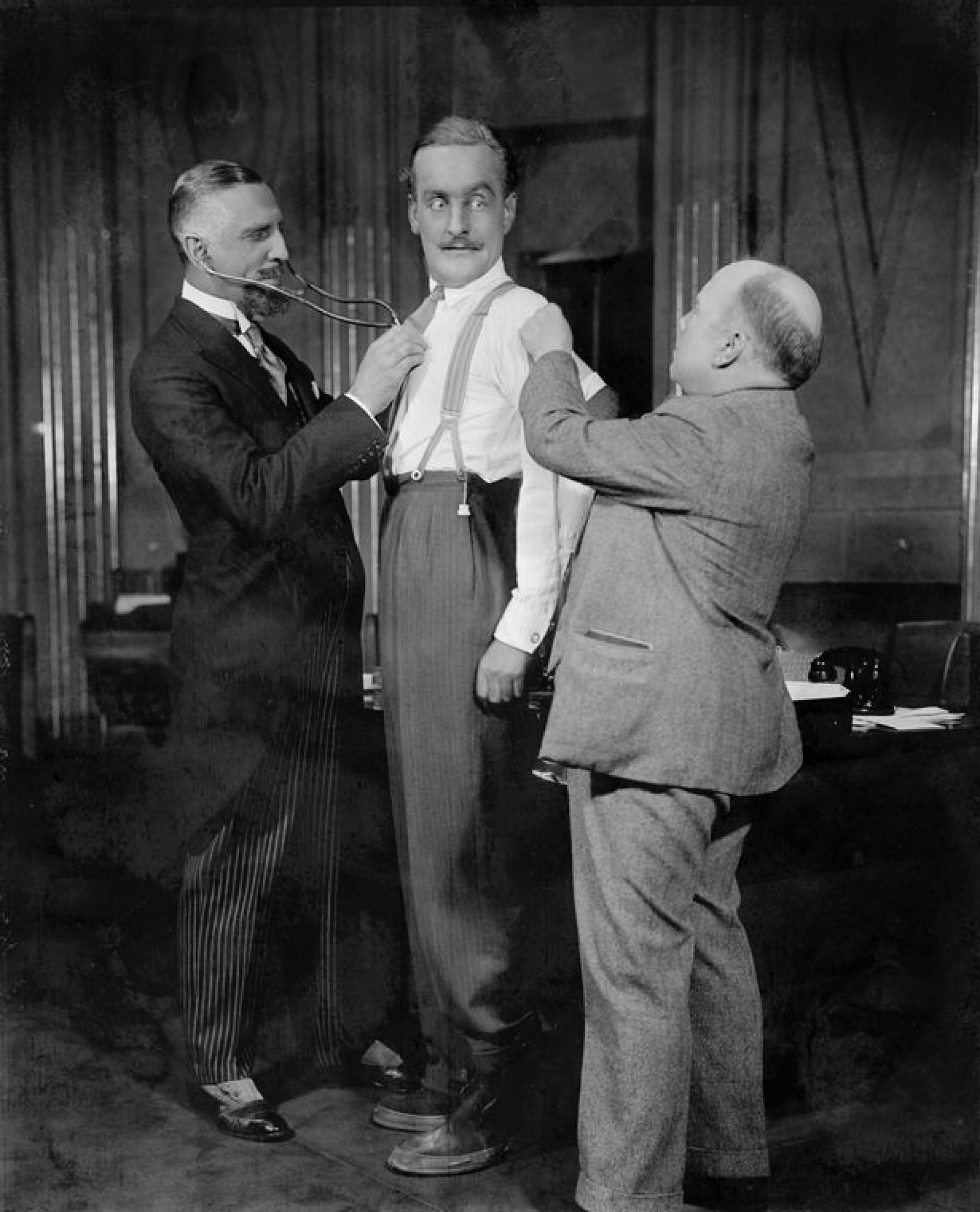

"Frederick Roland (Dr. Pinski), John Williams (Anton Schuh) and Donald MacMillan (Kaldoorian, the tailor)," Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed November 27, 2017, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-...

Goodbye, Columbia: A Yiddish Playwright and the German Stage

Sonia Gollance

When I told my advisors I wanted to write about Dovid Pinski in my dissertation, I half expected them to warn me against it. After all, I was getting a PhD in Germanic Languages and Literatures, and Pinski had dropped out of a PhD program in German literature at Columbia University. Even though I worried it might be tempting fate to delve into someone’s choice to leave a graduate program in my field, I was fascinated by Pinski’s decision to start and end his German literary studies. I soon found out that Pinski was much more involved in German intellectual circles than I had anticipated, even though he ultimately did not pursue an academic path.

Pioneering writer and playwright Pinski (1872-1959) bridges Yiddish and German theatre. He is best known for works that explore the psychological motivations of his characters or depict the lives of working class protagonists, such as in his 1906 play Yankl der shmid (Yankl the Blacksmith). Born in Mohilev, Russia (now Belarus), as a young man Pinski spent several years in German-speaking countries. He moved to Vienna (where he had intended to study medicine) and Berlin (where he actually studied philosophy and literature at the university), and married his wife, Adele, in Geneva, Switzerland. After immigrating to New York in 1899, Pinski began doctoral studies in Germanic Languages and Literatures at Columbia University. His papers at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research (RG 204) include a bursar’s receipt (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1) from the 1903-1904 academic year: Pinski was simply charged a $5 matriculation fee.

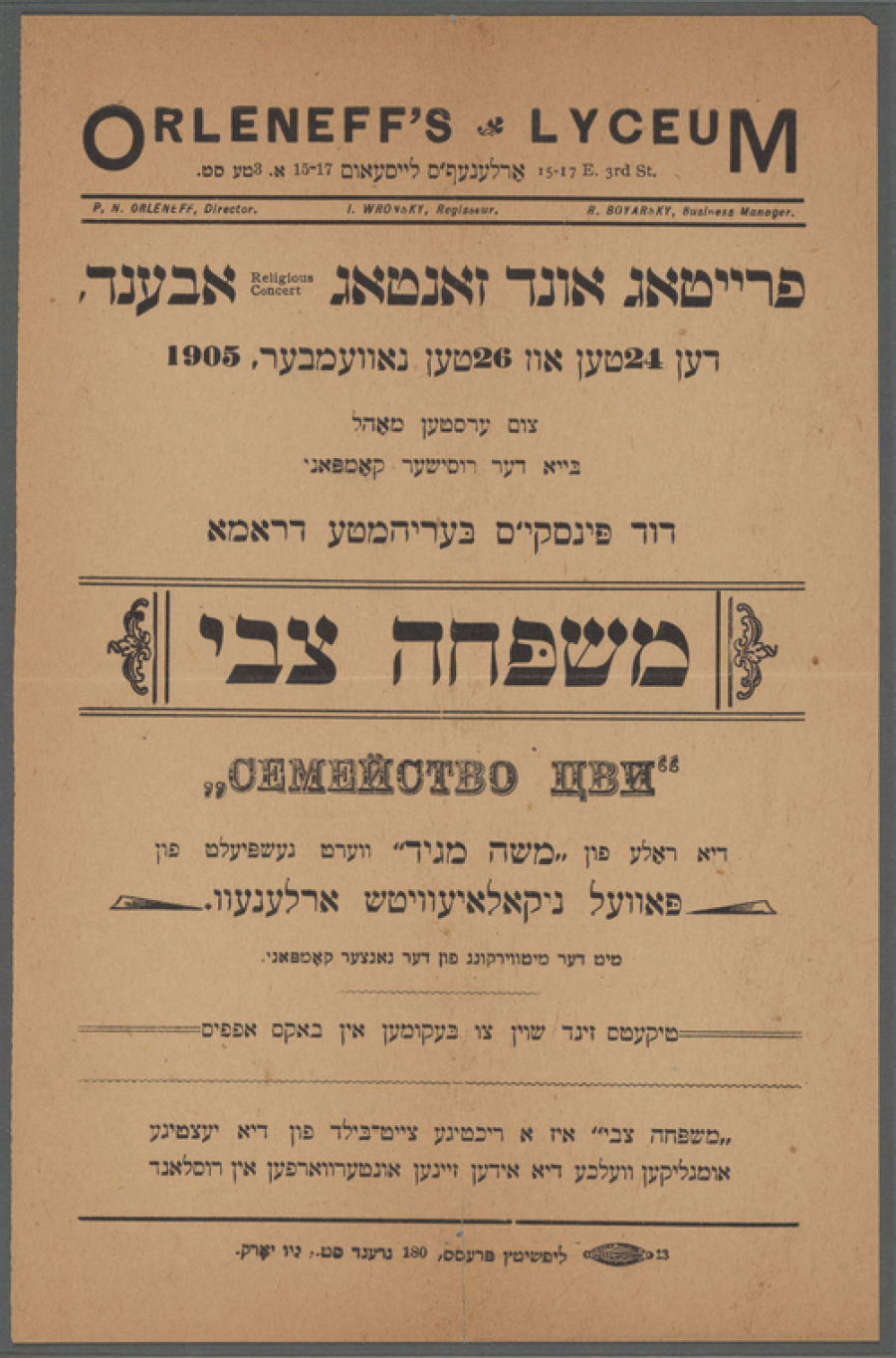

Family Tsvi, Dorot Jewish Division, The New York Public Library, New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed November 27, 2017, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c6856910-…

Sources differ about the exact nature of Pinski’s departure from the doctoral program. According to the biographical sketch in the Finding Aid for Pinski’s papers at YIVO, “In 1904, he nearly received his doctorate in German language and literature from Columbia University, but his play Family Tsvi [Di familye Tsvi] premiered on the day set for his Ph.D. examination. He failed to show up for the exam, and never received his doctorate.” Ben Furnish recounts this episode in a less dramatic fashion: “While working on [Family Tsvi], Pinski had enrolled in Columbia University’s doctoral program in German literature. When confronted with the choice of finishing his third act or preparing for his examinations for a degree, Pinski opted to finish the play and abandoned the idea of an academic career.” 1

With the help of Columbia University archivist Jocelyn Wilk, I was able to locate Pinski’s academic records. His registration reveals that he was only enrolled for a year, which suggests that he opted for a career in the theatre early in his graduate studies.

2

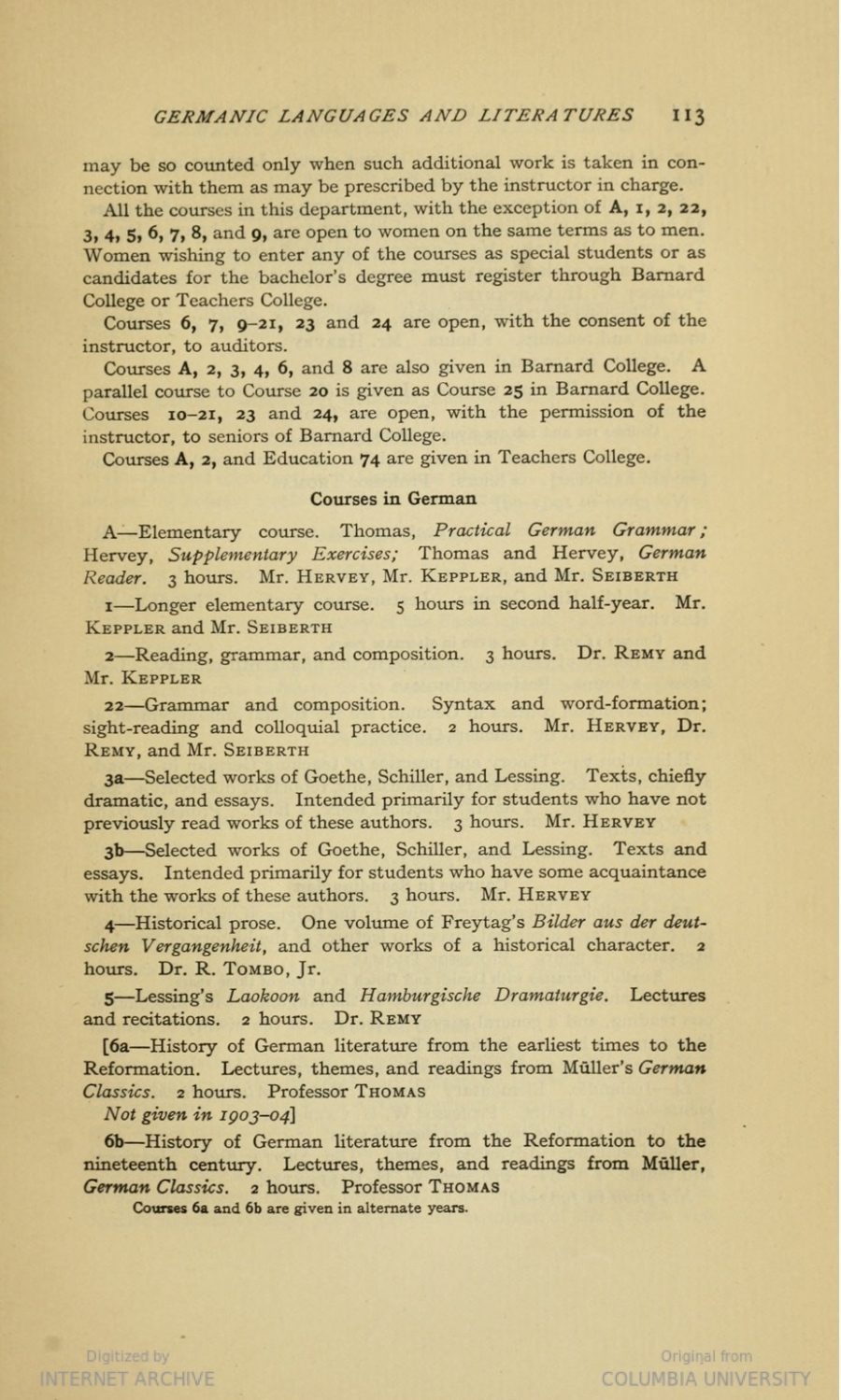

He was enrolled in Germanic Languages and Literatures with minors in Germanic Languages and Literatures and English. His four courses were: German 6b: “History of German literature from the Reformation to the nineteenth century,” 2 pts, May ’04 no return; German 7: “Goethe’s Faust: First and second parts,” 2 pts, May ’04 no return; German 9: “History of the German language,” 2 pts, May ’04 no return; English 40: “Epochs of the drama,” 2 pts, May ’04 no mark.

3

Pinski’s course selection was split between surveys in German studies at an introductory level and classes that focused on theatrical works.

Courses offered by the Columbia University Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures in 1903-04, Columbia University of the City of New York Catalogue and General Announcement: 1903-1904, 113.

Throughout his career, Pinski combined his dedication to Yiddish literature with an awareness of German culture. While I have so far been unable to ascertain the precise motivations for Pinski’s German literary interests, or if he had a potential dissertation topic in mind, his course registration information from both Berlin and Columbia includes enrollment in classes on Goethe’s Faust (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1). It is also unsurprising that a playwright who lived in fin-de-siècle Vienna was interested in psychological drama. Pinski’s brief academic career seems to have been the symptom, rather than the cause, of his engagement with German culture.

Pinski came to prominence as a Yiddish writer and playwright, yet his connection to German theatre and cultural life was strong. What is more, his work was recognized by the German intelligentsia. Pinski’s social-psychological play Eisik Sheftel (first published in Yiddish in 1907) was translated into German by no less a personage than Martin Buber (1904), and his work was also performed in German by Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theatre in Berlin. German-Jewish journals, such as Menorah: Jüdisches Familienblatt für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Literatur (Menorah: Jewish Family Paper for Science, Art and Literature), solicited his writings, and arranged for them to be translated into German (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1111). A letter from February 1, 1931 notes that Menorah only had about nine subscribers in America and asked for Pinski’s advice in increasing this number. Pinski was also recognized in German-language works such as the Jüdisches Lexikon (Jewish Lexicon) (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1030).

Pinski’s papers contain correspondence with literary and cultural figures in German, including discussions of performances, translations, and publication of his dramatic and prose works. In a letter from October 21, 1909, Arthur Kahane, of Berlin’s Deutsches Theater (German Theater), commented on Pinski’s use of a Jewish female type: a girl who wants to get married at any price, saying that such a character should be portrayed sympathetically. Kahane added that the introduction of her bridegroom could be “eine ganz prächtige Scene” (an entirely splendid scene) (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 902). These remarks suggest that Reinhardt’s theater was – or attempted to be – involved with Pinski’s literary production. Nonetheless, on March 6, 1911, Kahane declined to put on a production of Pinski’s Miryam, explaining that he didn’t think it would be successful on stage.

Perhaps most striking is Pinski’s personal correspondence, especially in the context of changing German politics. Like many of his contemporaries, Pinski received many requests to be involved with causes, such as a 1916 letter from prominent German-Jewish American philanthropist Jacob Schiff on behalf of the Campaign for Jewish War Sufferers (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1232). As a prominent intellectual with ties to German-Jews, Pinski also received requests for help from Jews fleeing the Nazis. In June 1940, journal editor Emil Reich wrote to Pinski in German to ask for his help in arranging an affidavit for him and his wife to come to America. In his letter, Reich describes his life-long engagement with Jewish life in Vienna and his commitment to Zionism. In December 1940, Leonhard Ekstein wrote to Pinski in English on Reich’s behalf, pleading that he “help him out from this Nazi hell.” (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1197) It is unclear from the one-sided correspondence what, if anything, Pinski could do to help. Reich was deported to Theresienstadt.

It is tempting to end on this dark note, and observe that Pinski’s decision to leave his doctoral program meant he chose to avoid teaching Faust courses of his own well before Germany made its own Faustian bargain with Hitler. Yet Pinski’s continued engagement with German culture points to something larger: the interconnectedness of German and Yiddish among globe-trotting Jewish intellectuals in the first few decades of the twentieth century. In another letter, from Hamburg, handwritten in English in 1932, Isaak Markon wrote to Pinski on the occasion of Pinski’s sixtieth birthday (YIVO, RG 204, Folder 1097). In an era before social media, Markon read about Pinski’s birthday from a newspaper. He felt compelled to write to him and remind him of their connection. Thirty-five years before, when he was a student, Markon met Pinski’s then-fiancée on a train, and she told him to look up Pinski in Berlin. Pinski not only met with Markon, he even invited him over for dinner. Markon moved to Hamburg in 1928 and became an accomplished scholar and Jewish community librarian. In his letter to Pinski, he spoke warmly of this meeting of the minds between a noted literary figure and a scholar of Jewish Studies.

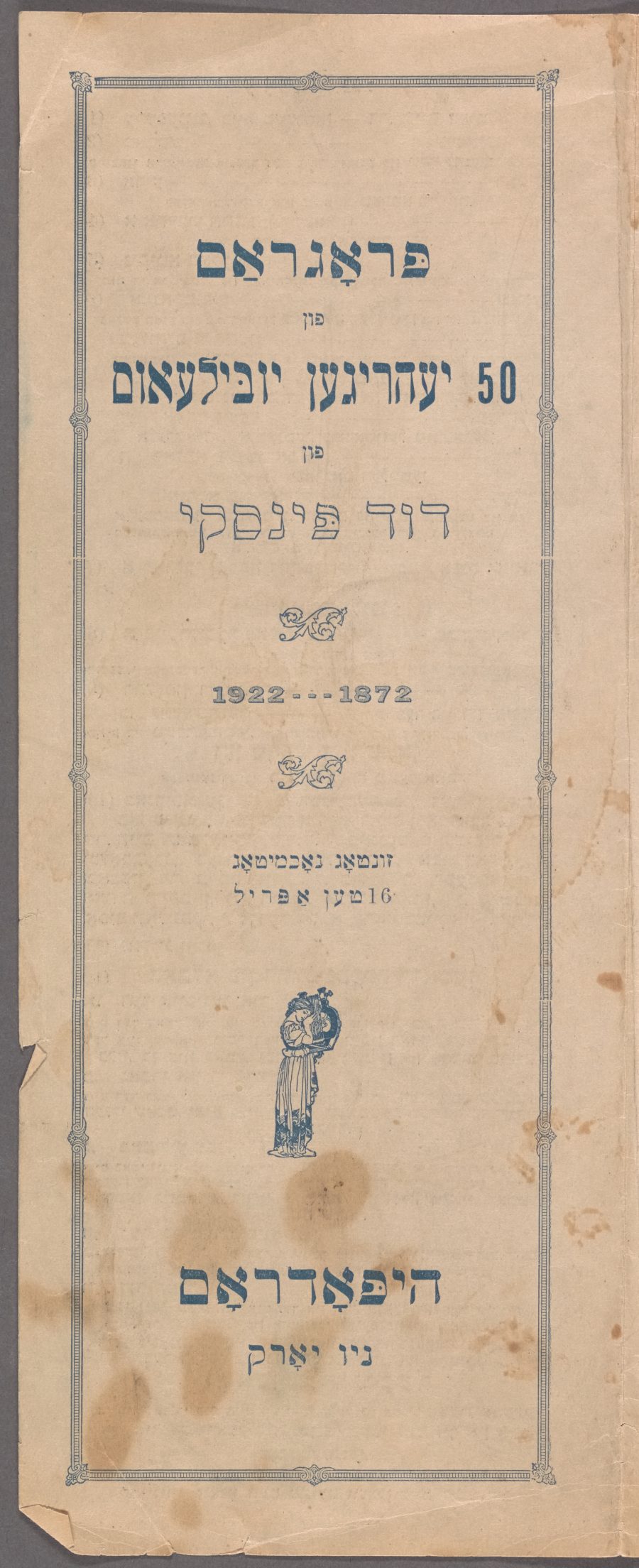

“Program for the 50 year anniversary of Dovid Pinski, 1872-1922, Sunday, April 16, 1922, Hipodrom, New Yorḳ,” Dorot Jewish Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed November 27, 2017, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6767c6c0-…

It was a happy coincidence, yet perhaps not shocking, that two Yiddish-speaking Russian Jewish students met in Berlin in the fin-de-siècle and reconnected several decades later, in English, as prominent intellectual figures living in new cities of their choice. Soon after his letter, Markon’s life in Hamburg, and the entire German cultural milieu that had been so beneficial for Pinski’s career, was irrevocably dismantled by the Third Reich. Nonetheless, the linguistic prowess Markon exhibited in his English-language letter to Pinski may have helped save him: after a rather peripatetic route, he ultimately found refuge in England. While Pinski may have initially embraced the support and seeming-stability of German cultural institutions, these ties proved to be as cosmopolitan and diasporic as Yiddish literary production.

Notes

-

1Ben Furnish, “David Pinski (Dovid Pinski) (15 April 1872 - 11 August 1959)”, in Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 333: Writers in Yiddish, ed. Joseph Sherman (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2007), 244.

-

2Pinski’s records are located in a Graduate Faculties grade book in Box 42, Office of the Registrar Records, in the Columbia University archives.

-

3See the Columbia University of the City of New York Catalogue and General Announcement: 1903-1904, 113-14; 108.