Paul Muni with Marguerite Churchill in The Valiant. The 1929 film launched Muni’s career as a movie star, after many years in the Yiddish theatre.

London - New York, or The Great British Yiddish Theatre Brain Drain

David Mazower

We Brits have been sending some of our finest actors across the Atlantic for as long as anyone can remember. Charlie Chaplin, Vivien Leigh, Kate Winslet, Christian Bale … the list goes on and on. Cue occasional bouts of US tabloid hysteria, and headlines about a British “invasion” or “takeover.” Or, on the British side, anxiety about a brain drain that weakens our own theatre. There’s not much evidence of that. British theatre is in rude health, and anyway it’s reassuring to know we are still able to produce something that other people want. Once upon a time, it was cars and coal. Now, actors and musicians are pretty much all we have left.

But I digress. The point is — an almost identical brain drain was happening more than a century ago in the Yiddish theatre. Around 1890, London switched from being a net importer to an exporter of Yiddish actors. And its main market was America. First, it was just the Lower East Side. Then, as the American Yiddish stage exploded into its all-singing, all-dancing heyday, it was the Bronx and Brooklyn, Chicago, Philadelphia and beyond. America’s Yiddish theatre managers sent talent scouts to Whitechapel, check books and ships tickets at the ready. The lucky few had their transatlantic passage paid for; many others simply took their chance in the world’s biggest Yiddish theatre city. The total number of Yiddish actors, playwrights, and musicians who left Britain in the years 1885 - 1915 probably runs into the hundreds. So who are the big names of this Yiddish theatre brain drain?

Like all lists, this one needs some house rules. So:

- No babies. Celia Adler, conceived in London, but born in America, isn’t eligible.

- No civilians. They’ve got to be in the Yiddish theatre already. That rules out Maurice Schwartz, who got separated from his emigrating family as a youngster and wandered the streets of London’s East End for two years before his father found him again.

- No transits. Pretty much everyone from Goldfaden to Mogulesco passed through London at some point. (One look at Whitechapel was usually enough to speed them on their way.) Unless they made Britain their home, however briefly, they’re out.

So here it is — my personal top ten list of Great British Yiddish theatre exports.

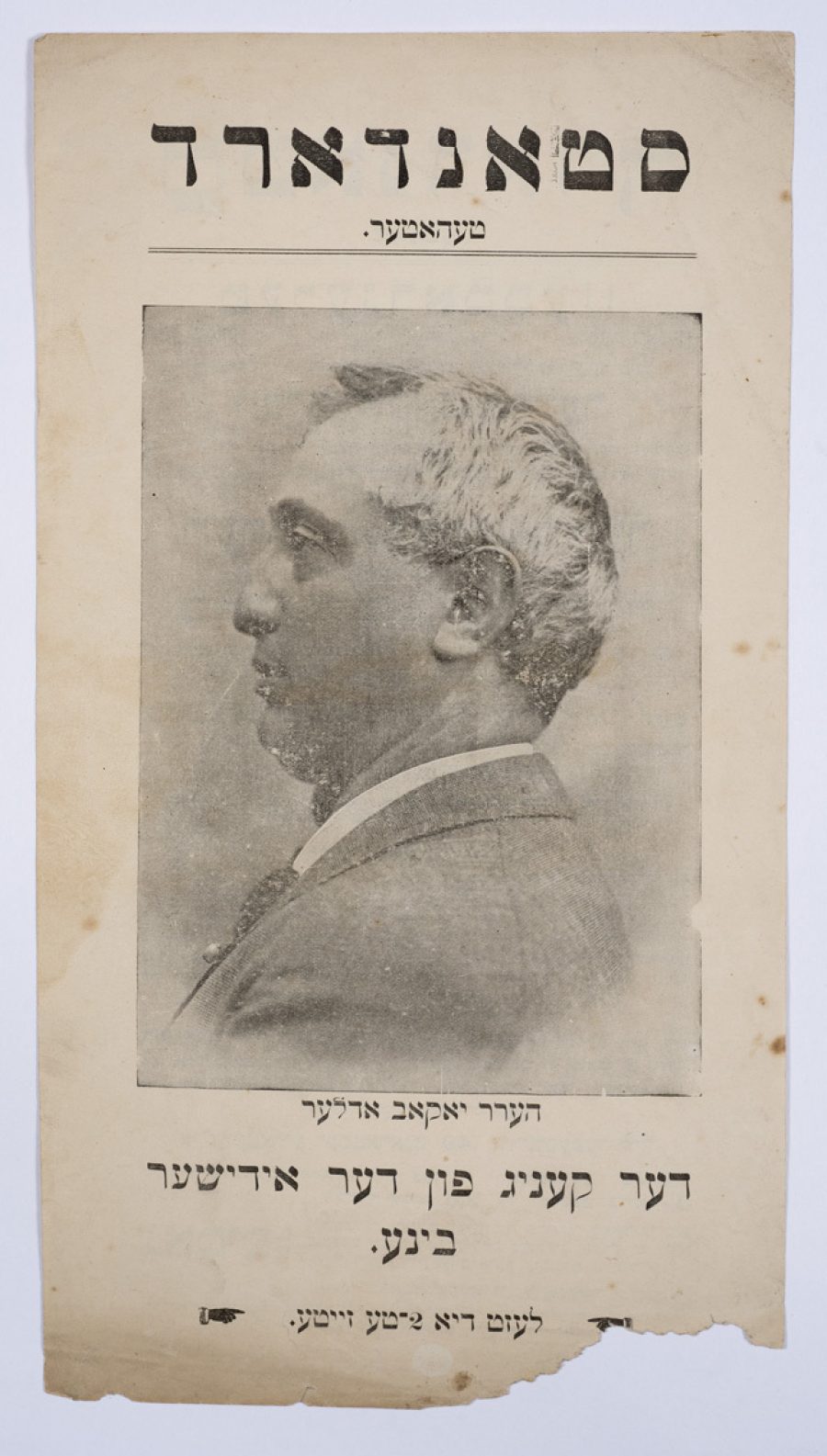

“Jacob Adler, the King of the Jewish Stage,” a handbill for a touring performance at the Standard Theatre, East London, c. 1900.

1. Jacob Adler (1855 - 1926)

Adler is the Big Daddy of the transatlantic Yiddish theatre brain drain, but he almost missed the boat — figuratively speaking. While Adler’s troupe was scratching out a living in the immigrant clubs of Whitechapel in the mid 1880s, stars like Mogulesco and Feinman hurried through London and grabbed the top spots on the Lower East Side. Adler was well aware of developments in New York, but for a long time “hang out with Whitechapel chorus girls” was higher on his to-do list than “buy tickets to New York.” He met Jenny Kaiser soon after he arrived in London. A child of the Whitechapel slums, she was a talented singer and actress, lustrous-eyed, fiery, and gorgeous. At age fifteen, she was pregnant with Adler’s child, and she gave birth to Solomon Adler at the still-scandalous age of sixteen. Solomon sneaks onto our list, too — he grew into a handsome teenager, changed his name to Charles Adler, and headed off to New York to meet his famous siblings and pursue his own showbiz career. But it took the deaths of seventeen audience members, trampled and suffocated in a panicked exit from the Hebrew Dramatic Club in Spitalfields in January 1887, to persuade Adler it was time to head west. Within a few years he was the King of Second Avenue.

Dina Feinman. Photograph courtesy of Fundación IWO, Buenos Aires.

2. Dina Feinman (c. 1869 - 1946)

Dina Feinman’s family came to London from Poland when she was a small child. She was about sixteen years old when she met Jacob Adler in London, at the same time as he was carrying on with Jenny Kaiser. In fact, both girls were in the chorus of his Russian Jewish Operatic Company, which must have made life … well, dramatic. Later on, as one of the leading Yiddish prima donnas in New York, she was often called “the Sarah Bernhardt of the Yiddish stage.” Feinman’s return appearances in London were big events. In 1909, a woman was crushed to death as the crowd surged towards the stairs to get the best gallery seats in the Pavilion Theatre for one of her shows. She was a popular figure in Whitechapel, though the critic Morris Myer, a hard man to please, thought she had picked up some bad habits in New York, and accused her of playing to the gallery rather than keeping in character.

Samuel Goldenburg. Courtesy of the Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

3. Samuel Goldenburg (c. 1886 - 1945)

Goldenburg was an aspiring actor and an accomplished, conservatory-trained musician in Warsaw who came to London to escape military service in the tsar’s army. Settling in the East End around 1905, he found London’s professional Yiddish theatre closed to him by jealous (and presumably inferior) colleagues. So he started his own amateur company in the Yiddish anarchists’ club on Jubilee Street. Sigmund Feinman gave Goldenburg his break in London around 1908, and the rest is Yiddish theatre history. After several years touring to South Africa and Argentina, Goldenburg became one of the most admired actors on the American Yiddish stage. He appeared with Boris Thomashefsky and in Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre, where he also worked as a voice coach. Goldenburg’s Broadway credits include the 1937 Jewish liberation epic The Eternal Road (a Kurt Weill/Franz Werfel/Meyer Weisgal production), in which he appeared as Moses alongside Lotte Lenya.

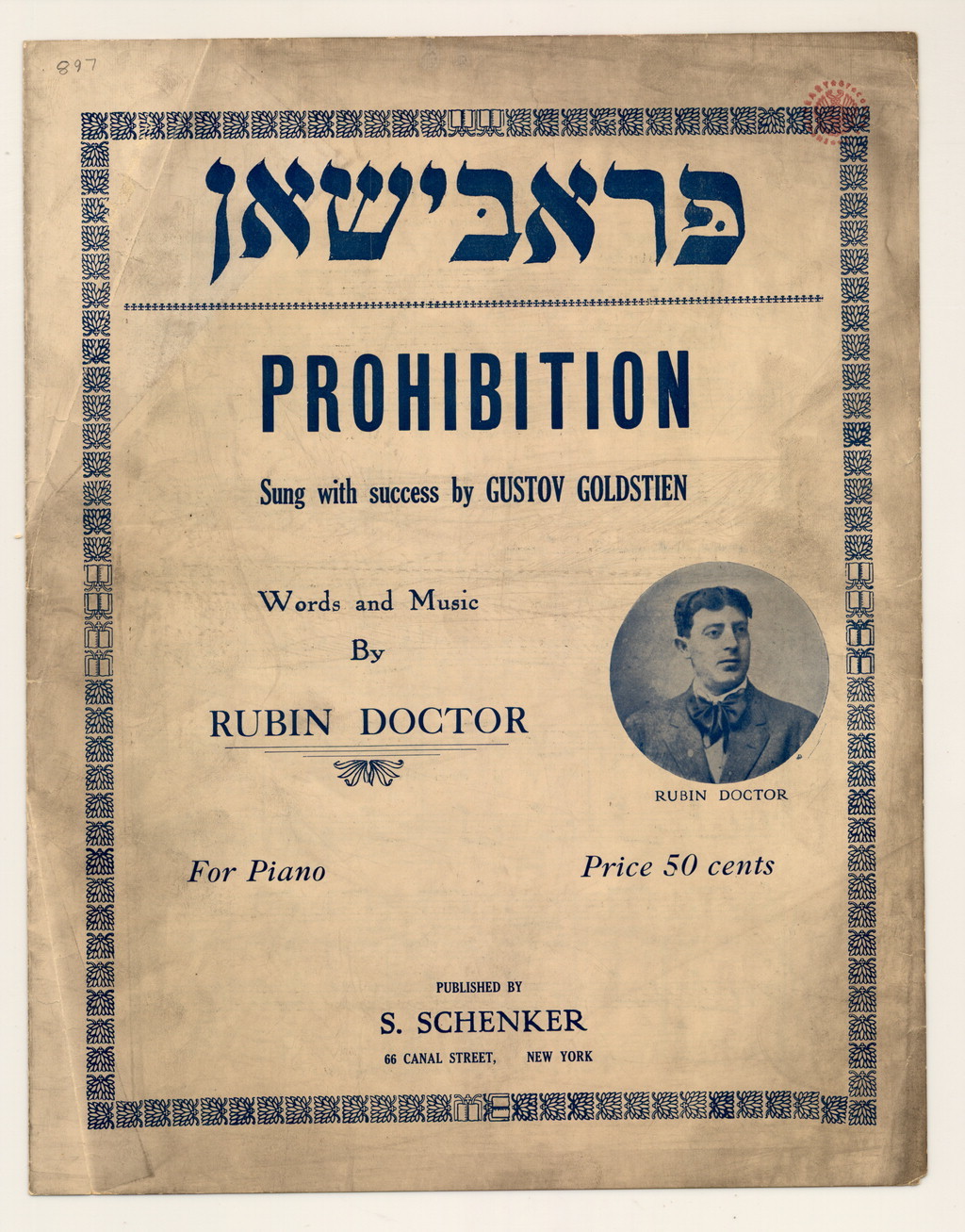

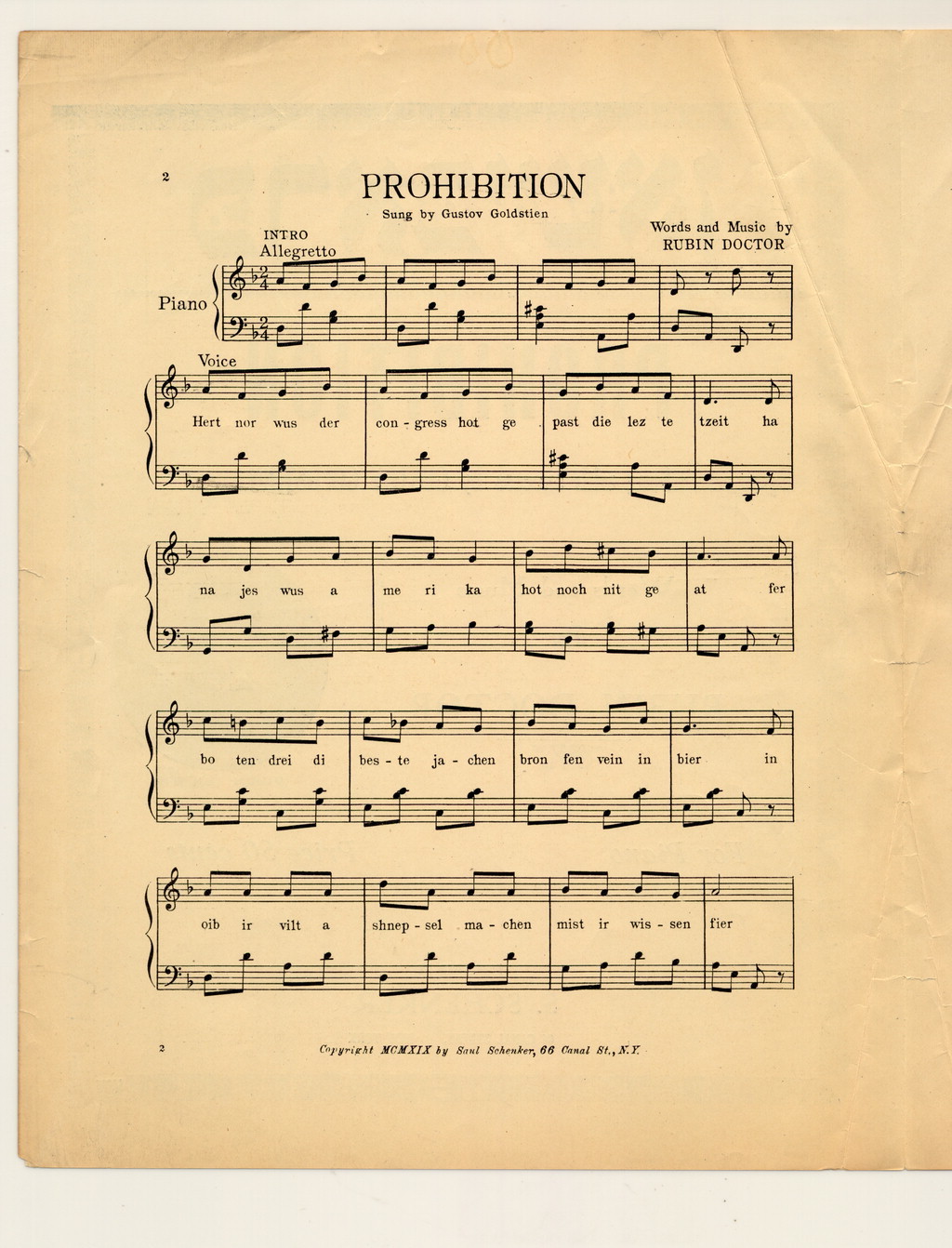

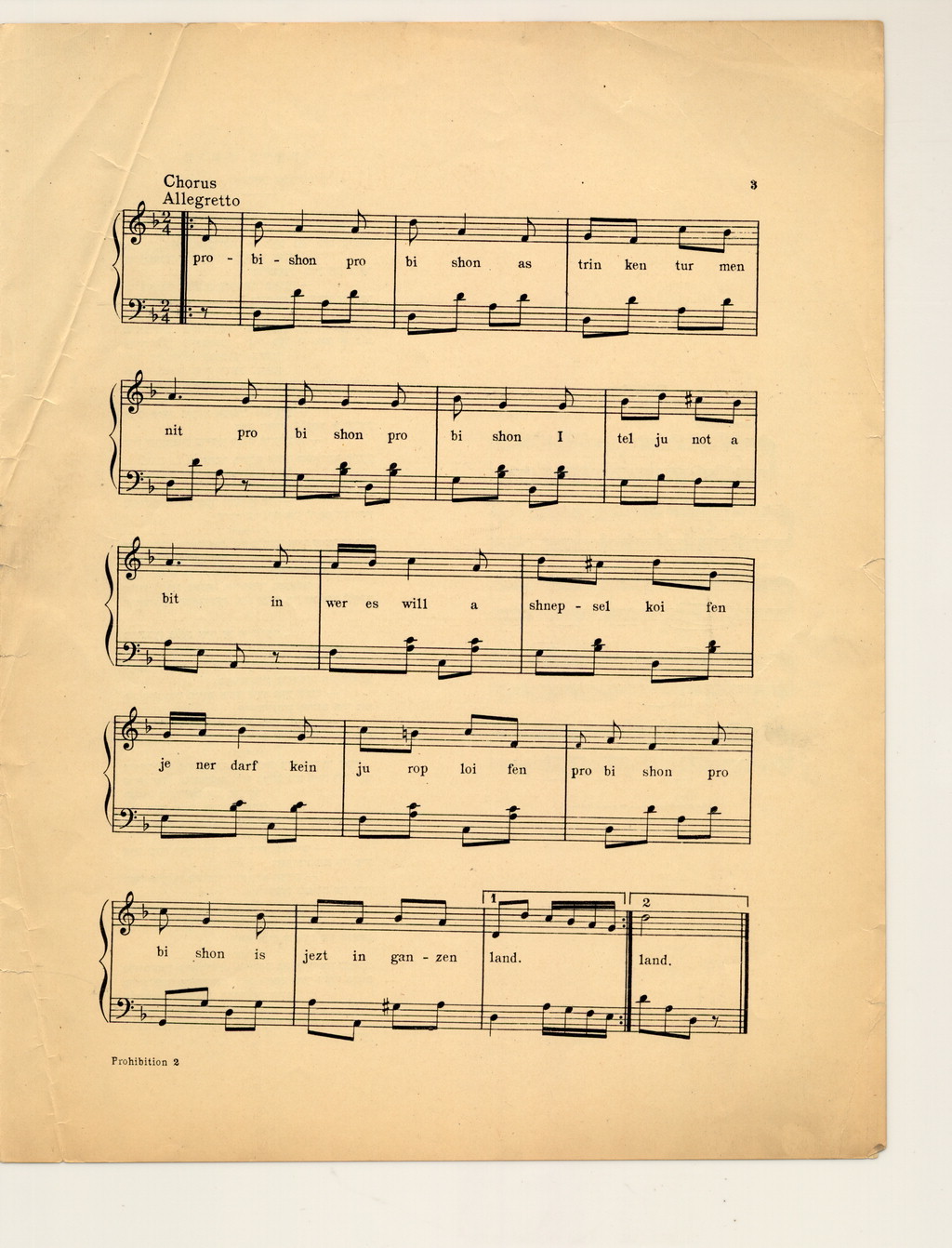

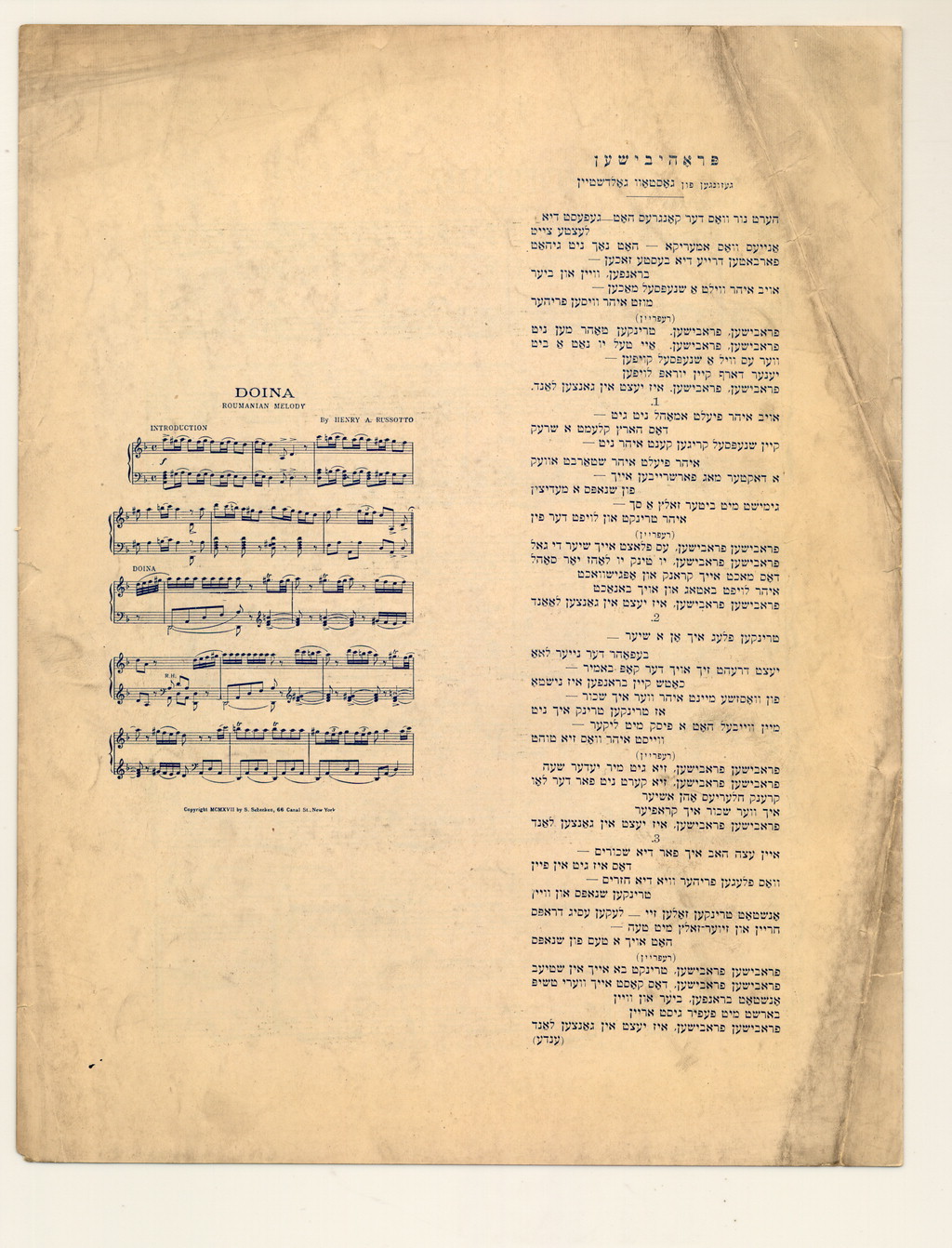

Rubin Doctor, “Probishon” (Prohibition), 1919. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 11 - 897.

Rubin Doctor, “Probishon” (Prohibition), 1919. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 11 - 897.

Rubin Doctor, “Probishon” (Prohibition), 1919. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 11 - 897.

Rubin Doctor, “Probishon” (Prohibition), 1919. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 11 - 897.

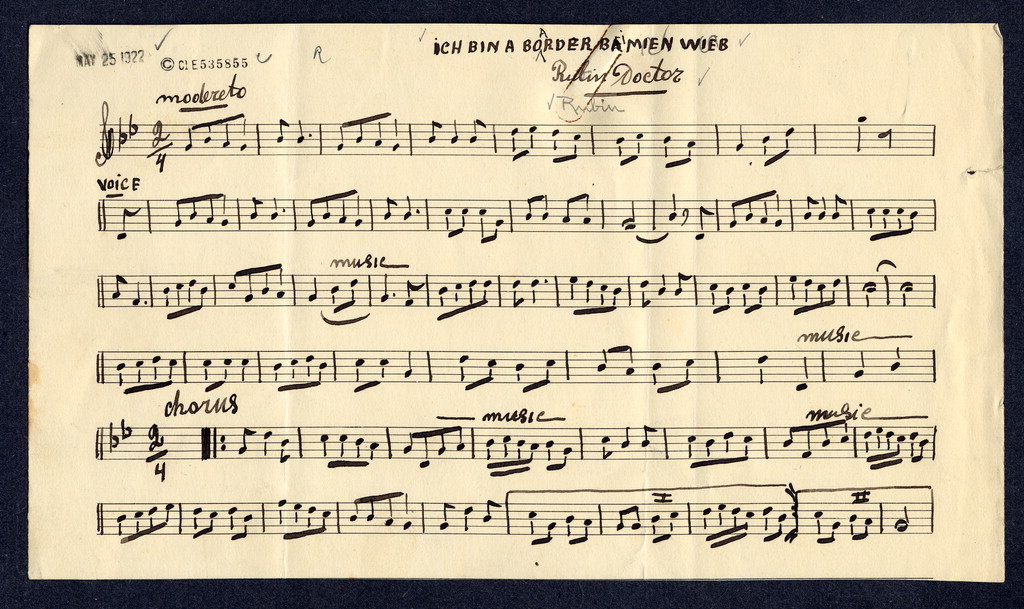

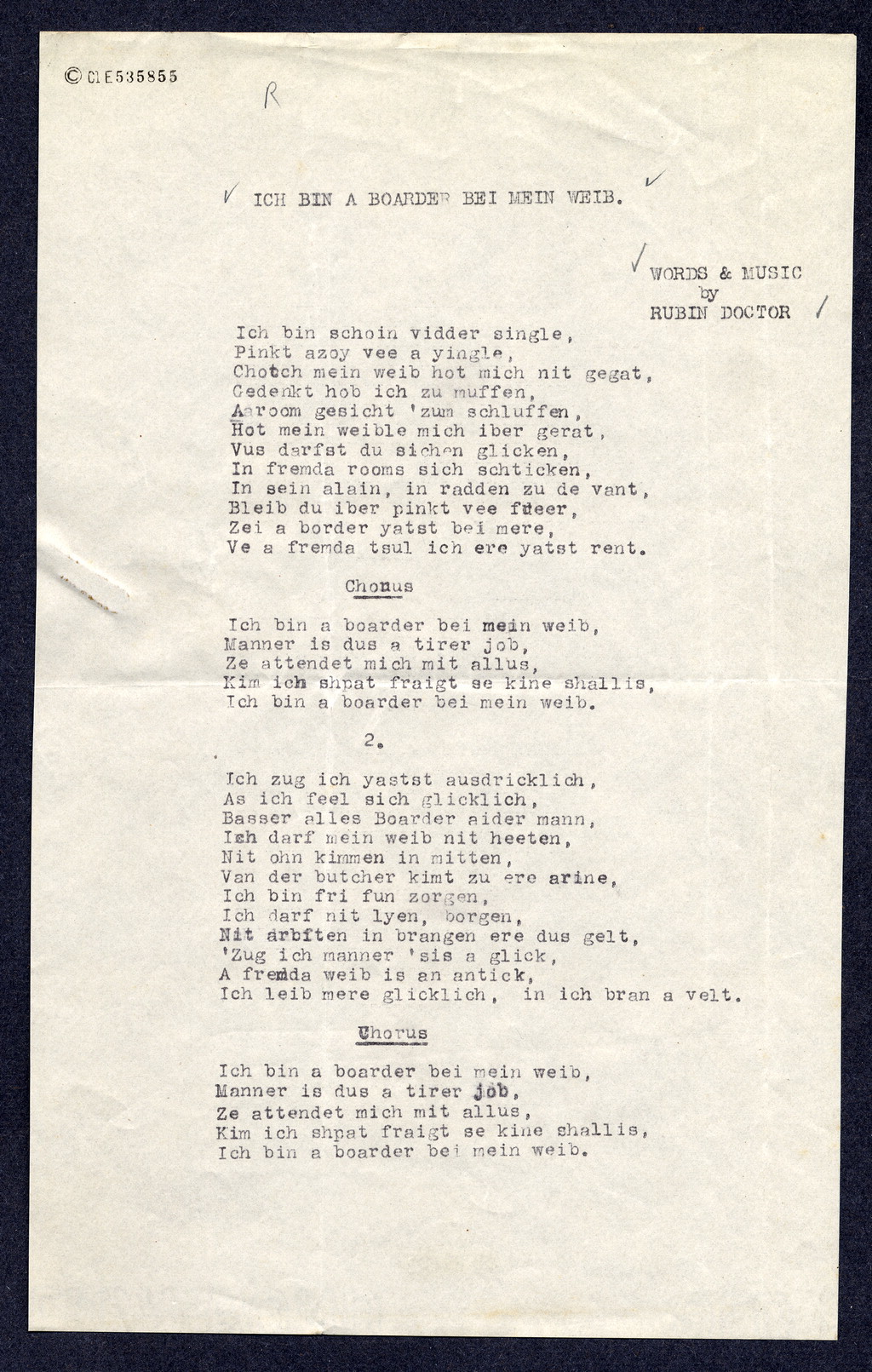

Rubin Doctor, “Ikh bin a border bay mayn vayb” (I’m a boarder at my wife’s place), 1922. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, C.D. Box 8-1248.

Rubin Doctor, “Ikh bin a border bay mayn vayb” (I’m a boarder at my wife’s place), 1922. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, C.D. Box 8-1248.

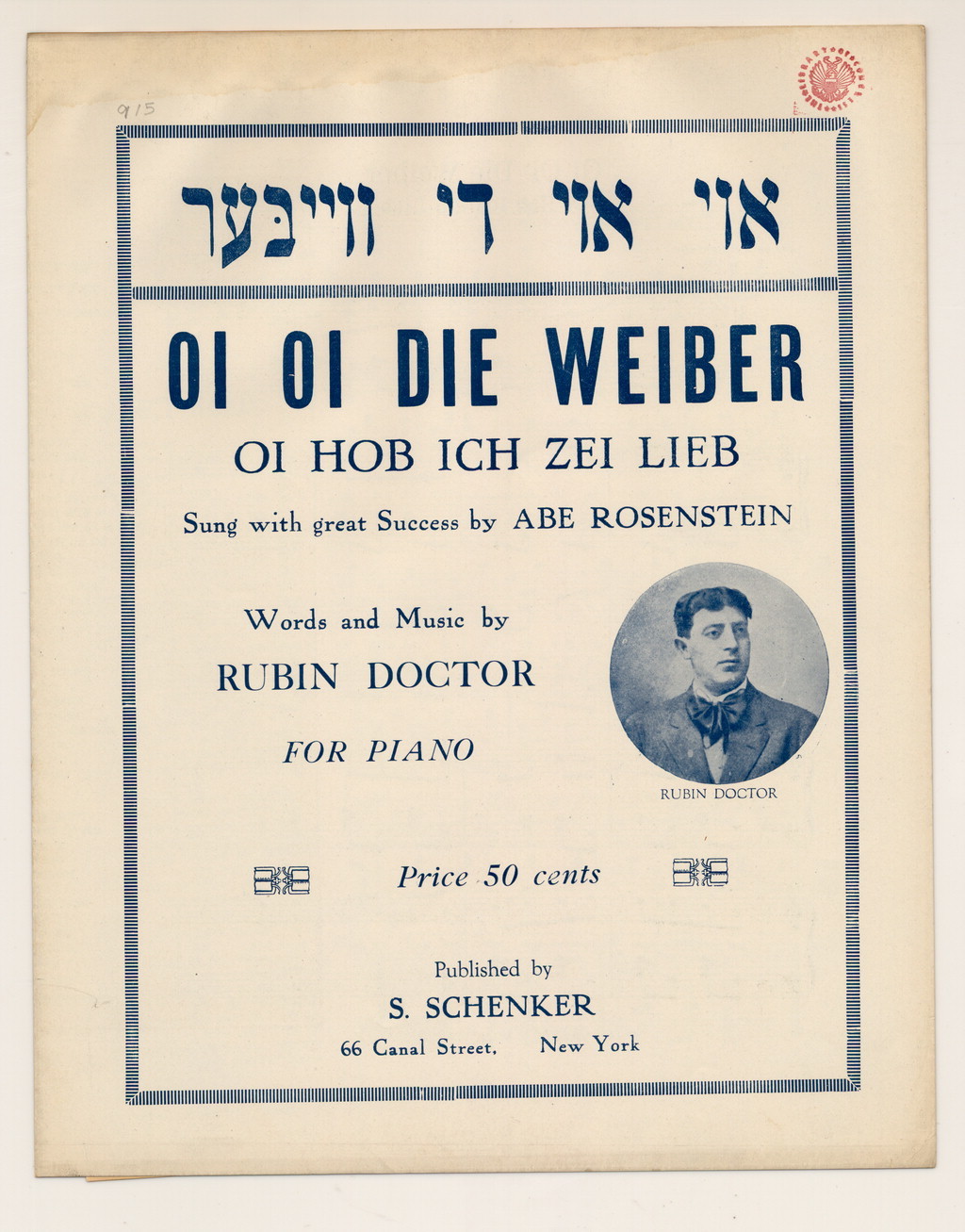

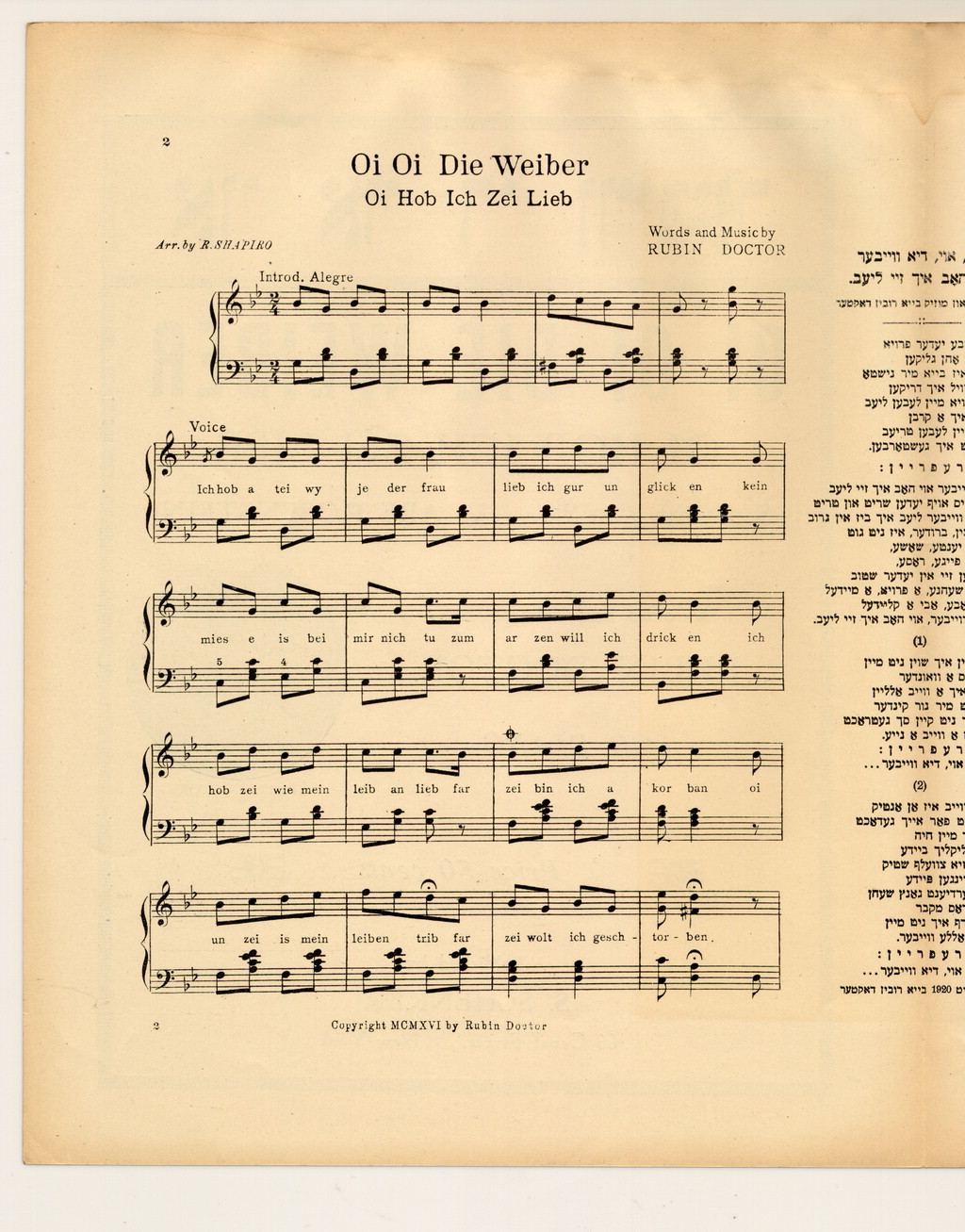

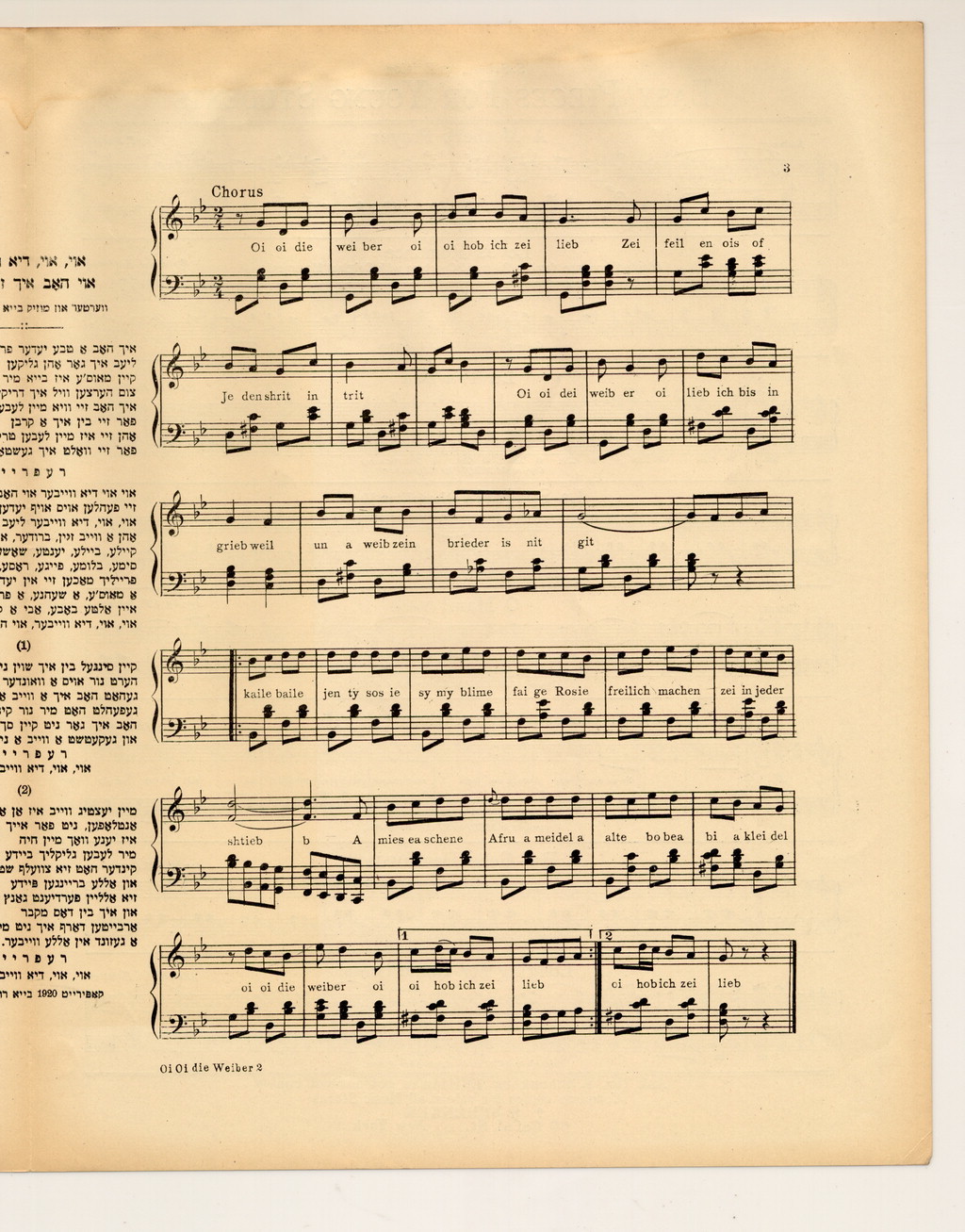

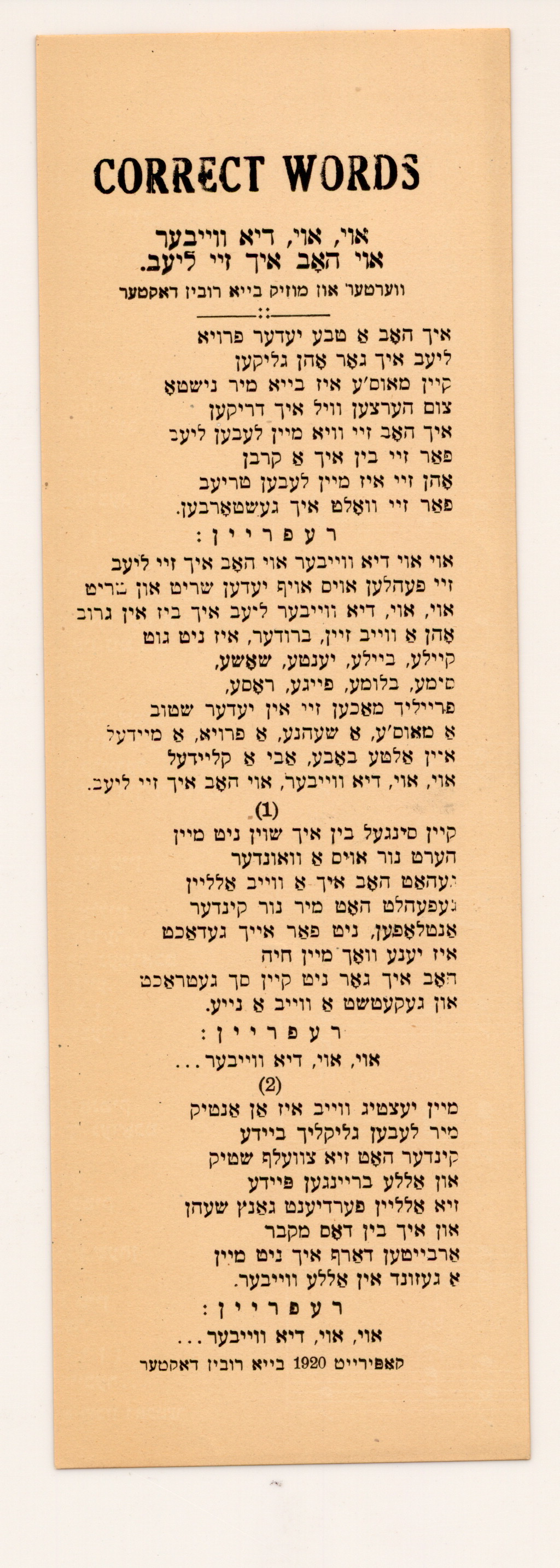

Rubin Doctor, “Oy, oy di vayber” (Oh, oh the wives), 1920, Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 12 - 915.

Rubin Doctor, “Oy, oy di vayber” (Oh, oh the wives), 1920, Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 12 - 915.

Rubin Doctor, “Oy, oy di vayber” (Oh, oh the wives), 1920, Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 12 - 915.

Rubin Doctor, “Oy, oy di vayber” (Oh, oh the wives), 1920, Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 12 - 915.

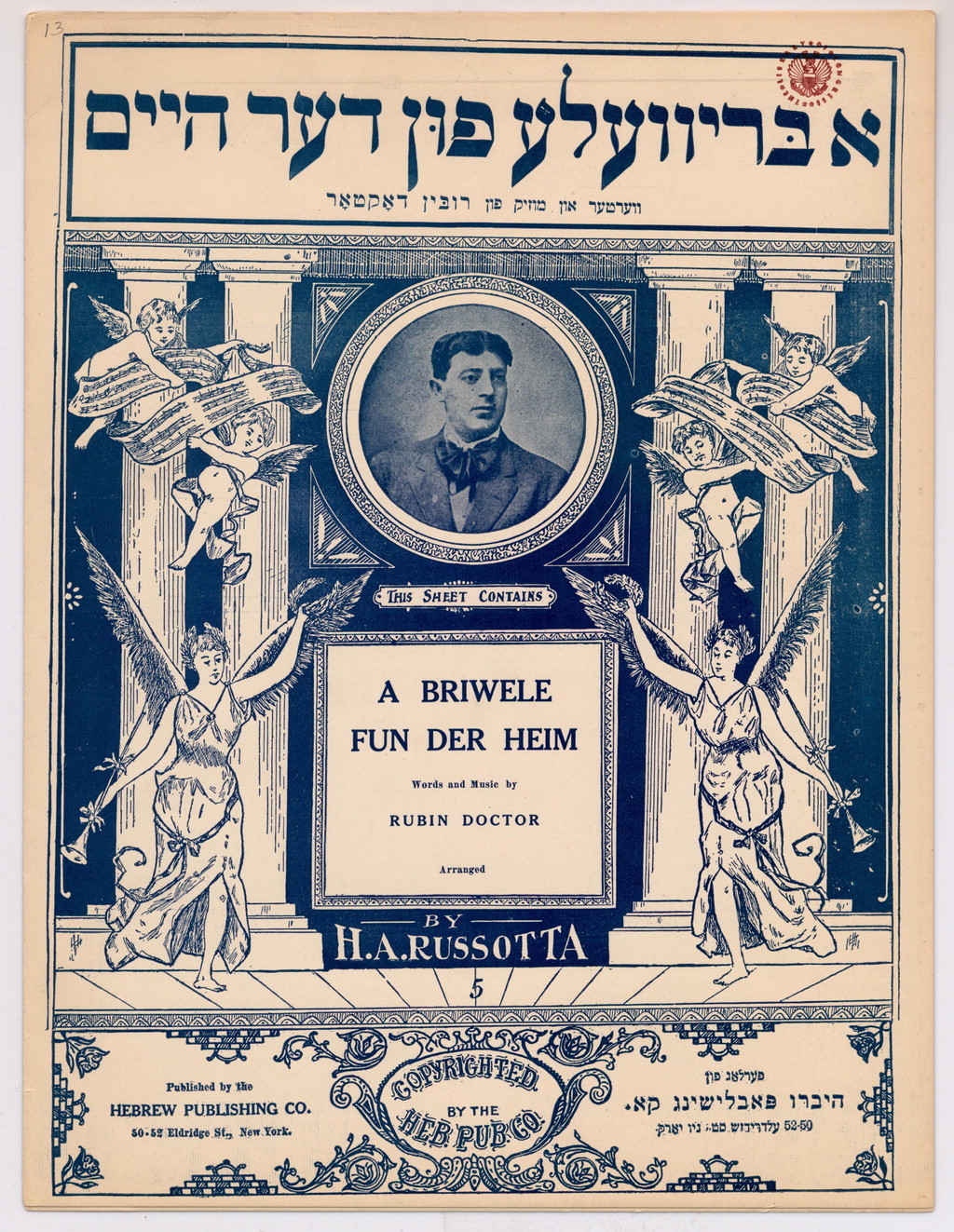

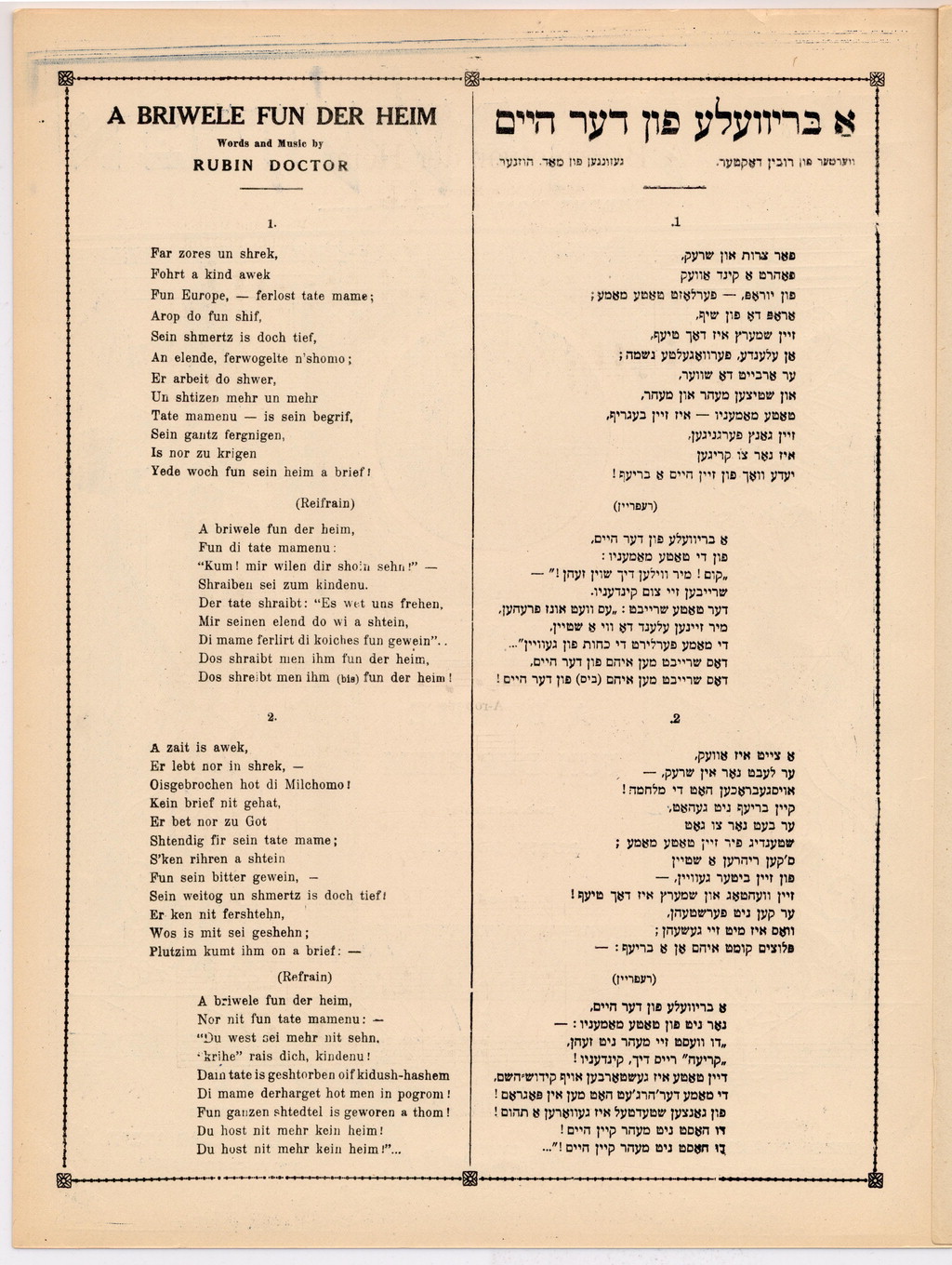

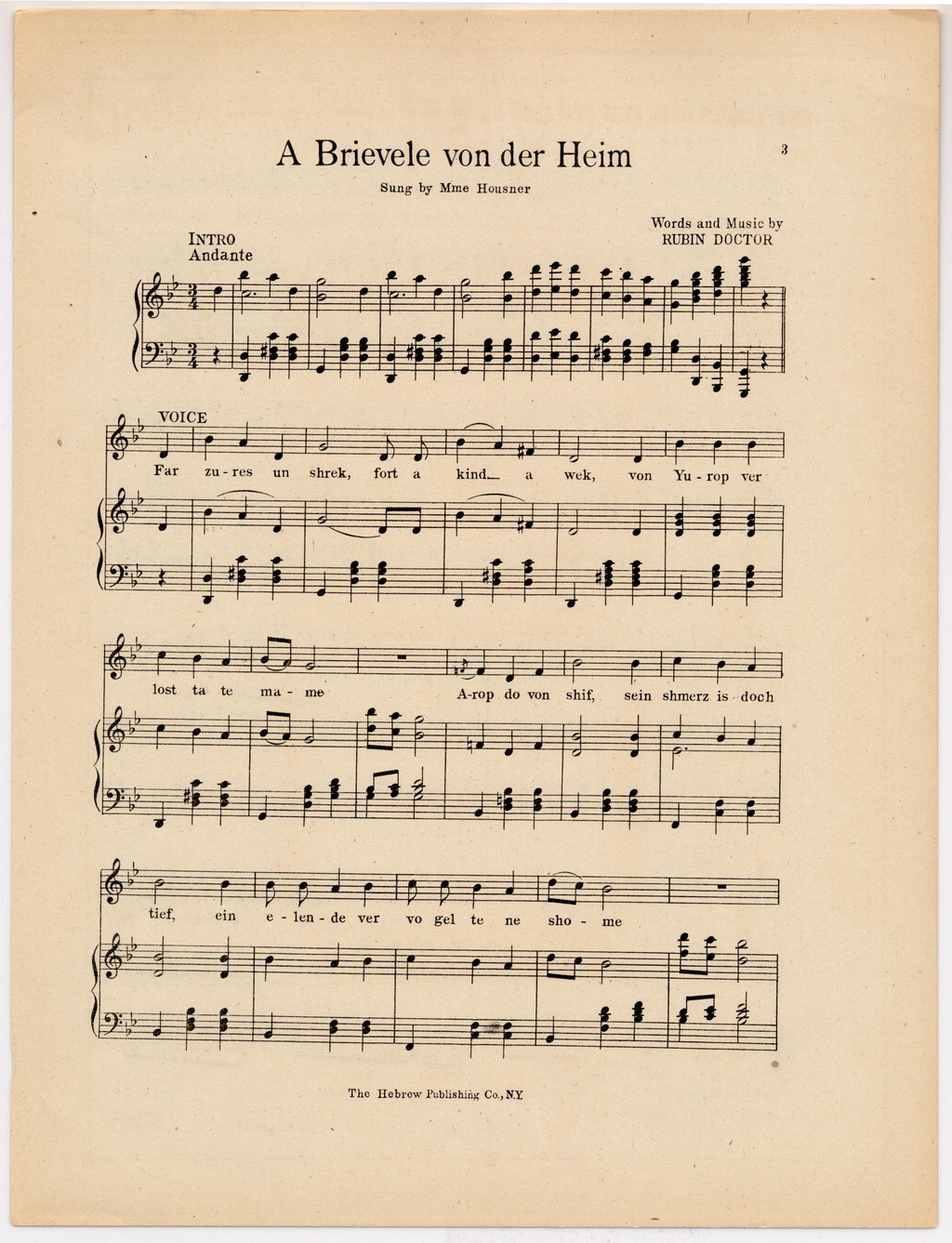

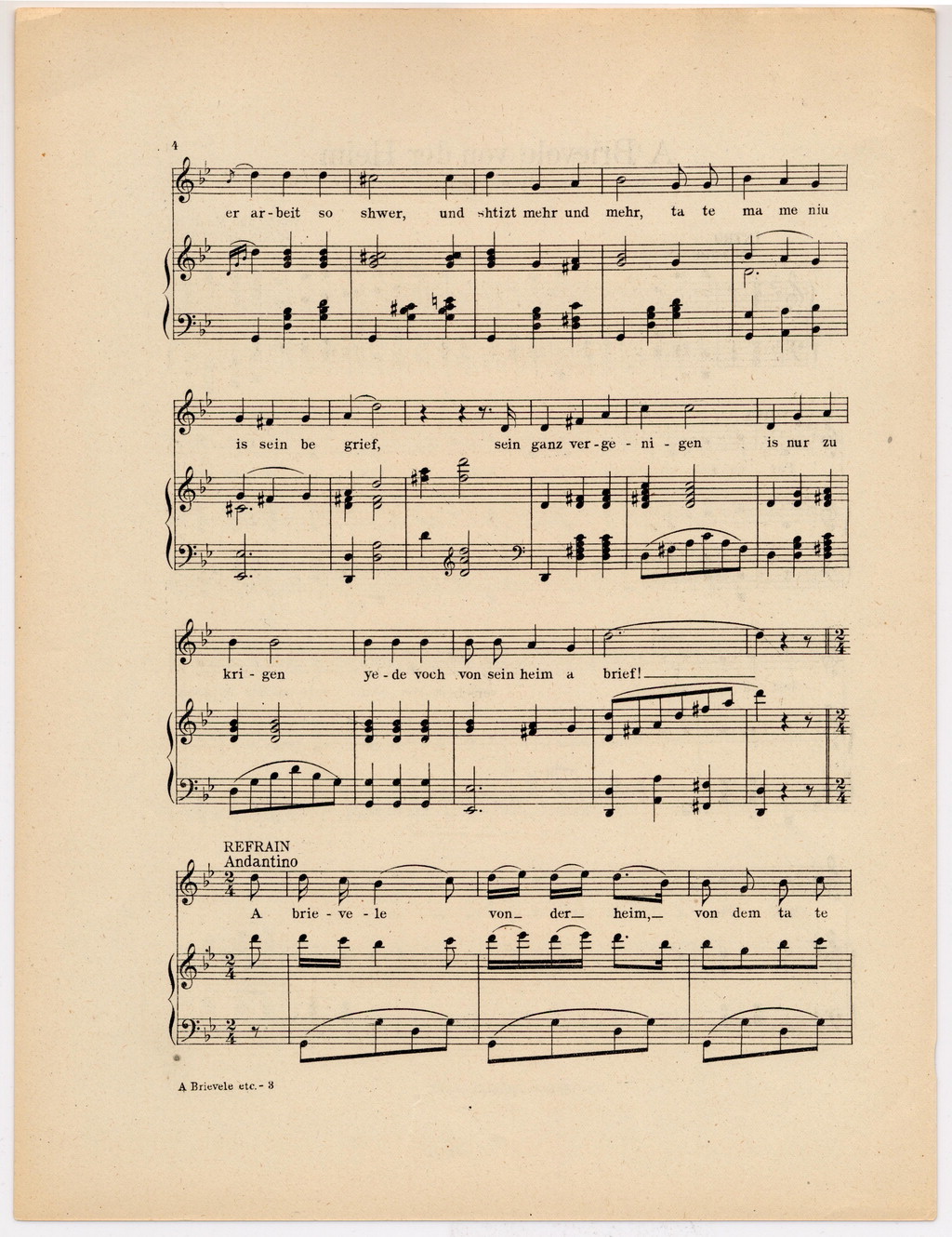

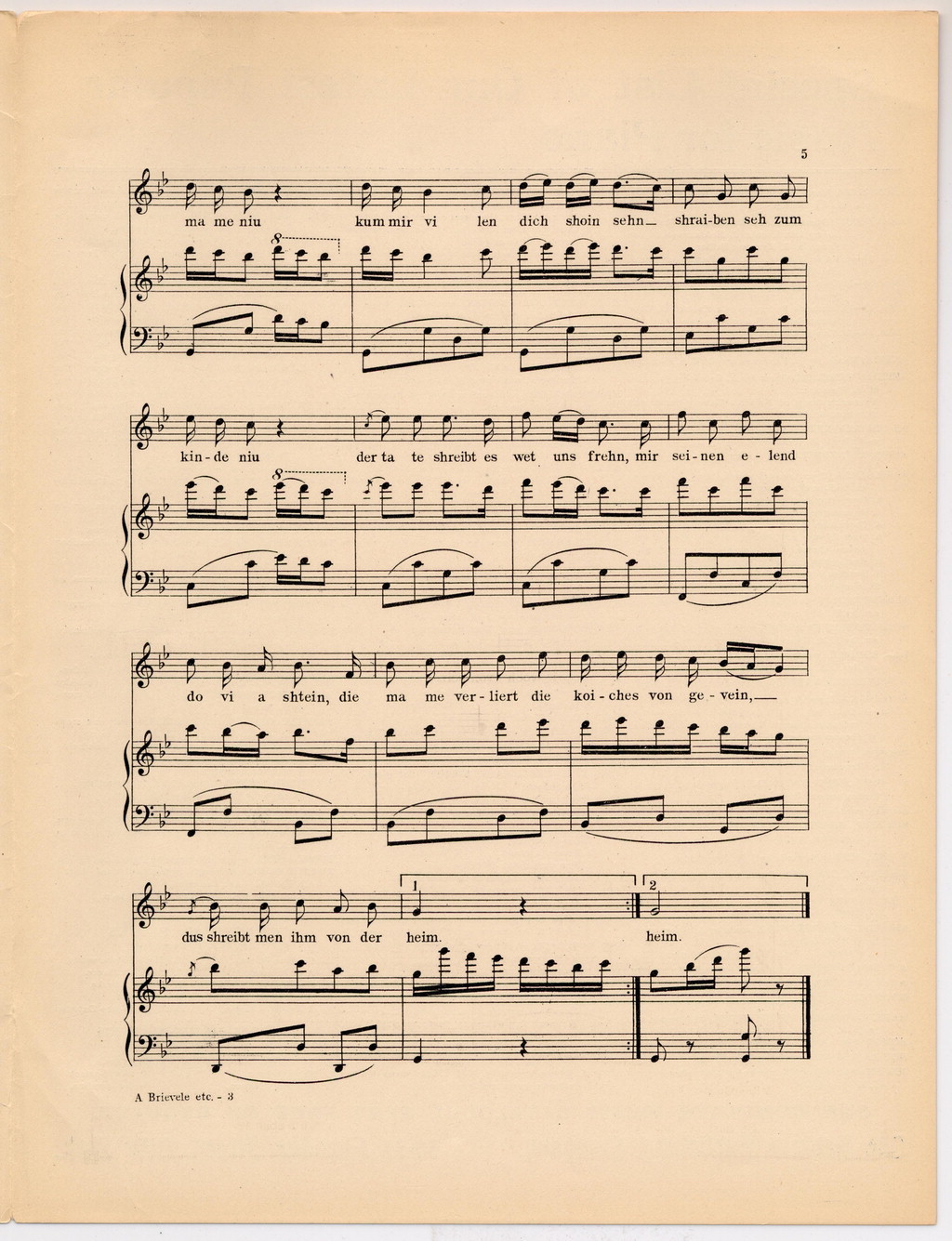

Rubin Doctor, “A brivele fun der heym” (A letter from home), 1897. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 1 - 13.

Rubin Doctor, “A brivele fun der heym” (A letter from home), 1897. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 1 - 13.

Rubin Doctor, “A brivele fun der heym” (A letter from home), 1897. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 1 - 13.

Rubin Doctor, “A brivele fun der heym” (A letter from home), 1897. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 1 - 13.

Rubin Doctor, “A brivele fun der heym” (A letter from home), 1897. Library of Congress, Music Division, Heskes Collection, Box 1 - 13.

4. Rubin Doctor (c. 1878 - c. 1940)

Rubin Doctor was a one-man hit factory. He wrote a succession of brilliant Yiddish novelty songs and yet almost everything about him is a mystery. He was probably born in 1878, but the Lexicon of Yiddish Theatre says 1882. Also, his surname was originally Stolon. We don’t know when he changed it to Doctor (though it’s pretty obvious why; wouldn’t you?). Born in Bessarabia, he came to London in the 1890s, performing in Yiddish music hall and working as a hairdresser. Ellis Island records show he left London in 1910, joining relatives already in America. He worked mostly in Yiddish vaudeville, published around a hundred songs, and recorded well over fifty. Herr Doctor was equally adept at schmaltz (“Ikh benk nokh mayn shtetele”/I miss my hometown) and comedy. His runaway hit “Ikh bin a border bay mayn vayb“/I’m a boarder at my wife’s place) had the ultimate accolade of its own parody. As theatre historian Joel Schechter writes, the brilliant Yiddish puppeteers Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler included a version of it in their play Biznes (Business), where the factory-owner puppet pleads, “I want to be the boss in my own business.” Seriously, folks, it’s a shande far di yidn (ridiculous) that Rubin Doctor remains so obscure. This cannot stand.

Rudolf Marks and Sigmund Mogulesco, New York, c. 1892.

5. Rudolf Marks (1867 - 1930)

In one of the most widely-reproduced of all New York Yiddish theatre photos, taken in the 1890s, three of the all-time greats – Jacob Adler, David Kessler, and Sigmund Mogulesco – face the camera with a few colleagues. Aping Mogulesco’s pose, elbows resting on the same stool, is the actor Rudolf Marks. It’s an in-joke. Marks and Mogulesco swapped roles in Goldfaden’s mistaken identity comedy The Two Kuni-Lemls and were said to be impossible to tell apart, to the consternation of Mogulesco’s many fans. It’s a faint echo of Marks’s chameleon-like genius. He came to London from Odessa in the 1880s, and was one of the earliest stars of the London Yiddish stage, as both a comic and dramatic actor and a prolific playwright. He also adapted many Victorian melodramas for the Yiddish stage (in an early example, The Stowaway became Der matroz oder der yosem in gefar/The Sailor, or The Orphan in Danger). Marks was equally popular as an actor in New York in the 1890s, but then, to his colleagues’ amazement, he left the stage and reinvented himself as a successful lawyer. Oh, and his father was the celebrated translator of the Talmud, Michael Levi Rodkinson. Max Rodkinson became the actor Rudolf Marks in order not to upset his father, but changed his name back to Max Rodkinson when he took up law. Chameleon-like to the end.

Bessie Thomashefsky in Rakov’s play Der griner bokher (The Green Boy), People’s Theatre, New York City, 1905.

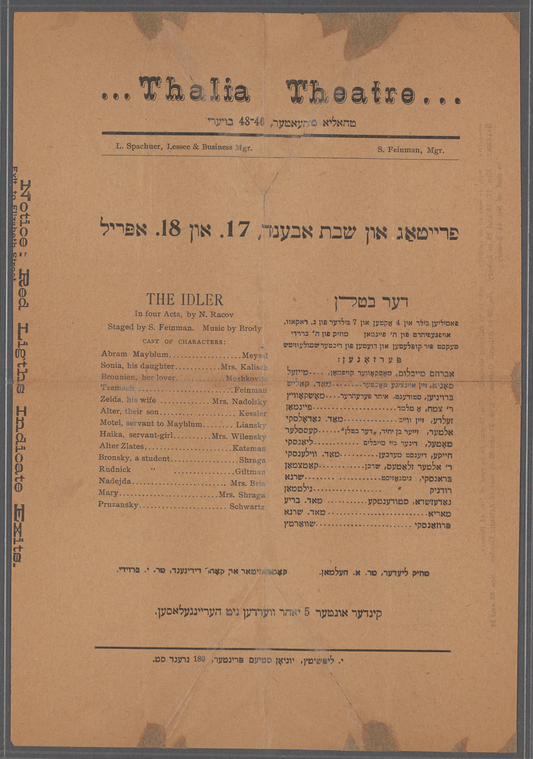

Rakov’s play Der batln / The Idler at Thalia Theatre, New York City, 1903.

Poster for Rakov’s play Ver iz di froy? (Who Is the Woman?) at Salon Garibaldi, Buenos Aires, 1924. Nachman Falbel Collection.

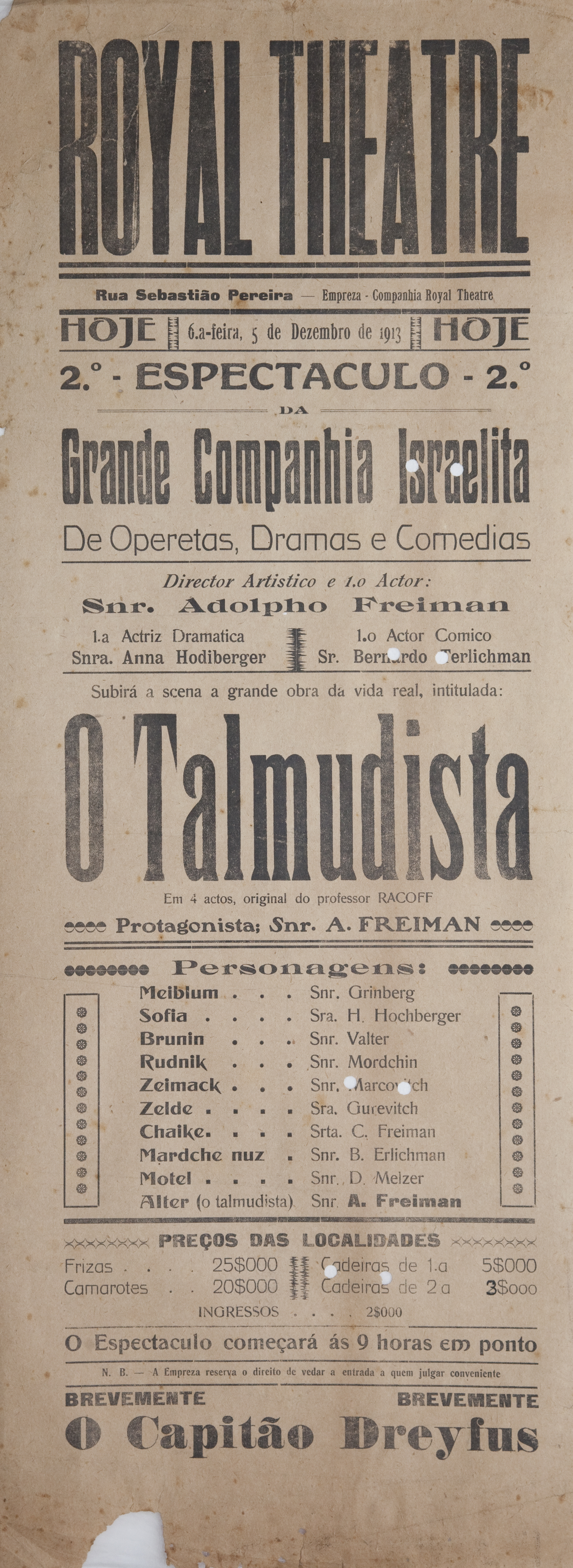

Poster for Rakov’s play O Talmudista (The Talmudist) at the Royal Theatre, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1913. The poster states that “entry will be refused to those deemed inappropriate” i.e. traffickers in women, and prostitutes. Nachman Falbel Collection.

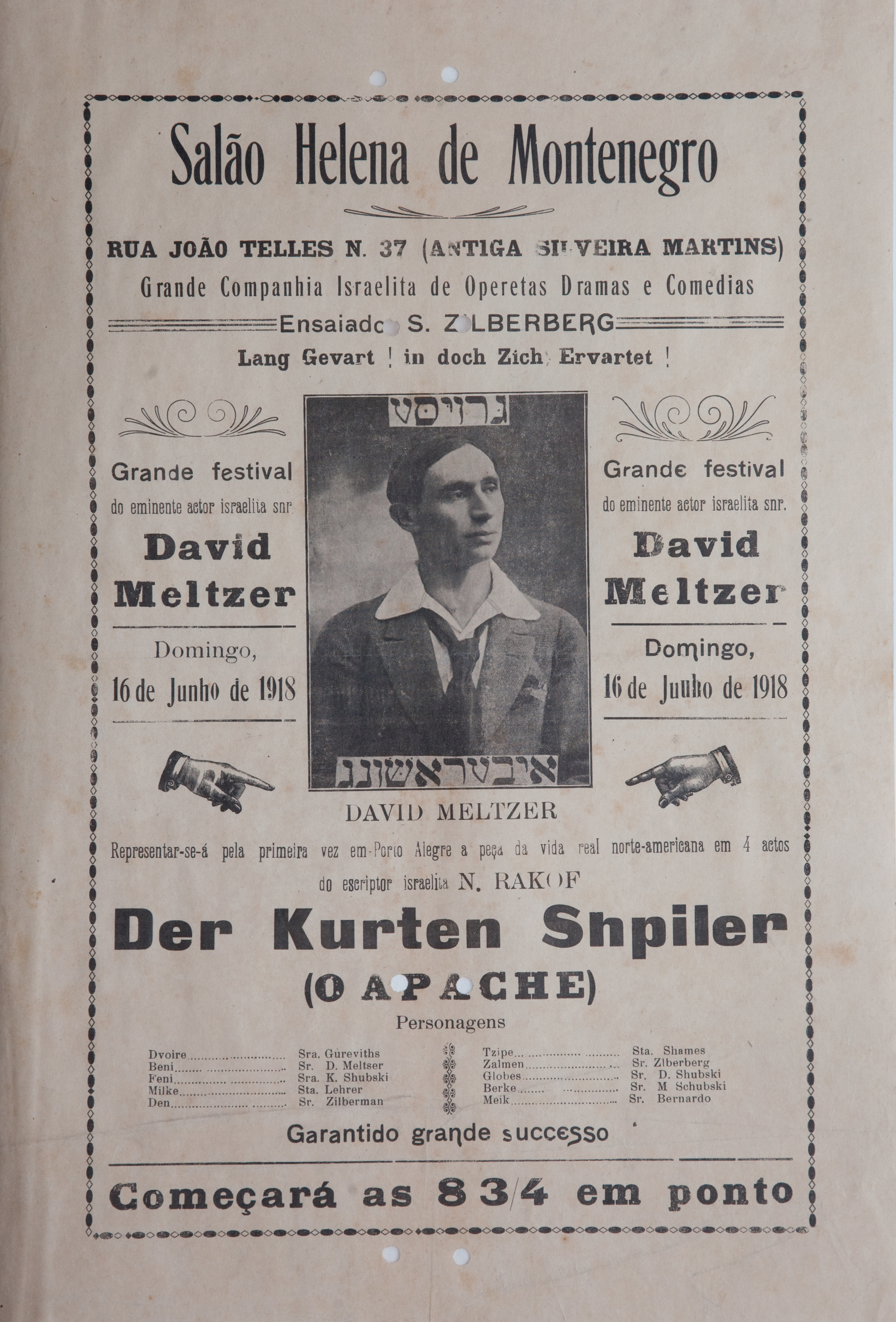

Poster for Rakov’s play Der kurten shpiler (The Card Player) at Salao Helena de Montenegro, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1918. Nachman Falbel Collection.

6. Nahum Rakov (1866 - 1927)

Rakov was a prolific and successful playwright who was often accused of plagiarism or re-working other dramas. He was born near Vilna, Lithuania and came to London in the mid 1880s, working as an actor, prompter, playwright, stage manager, and occasional commercial traveler. His first play was Der griner in london oder der misioner (The Greenhorn in London or The Missionary). He must have thought the title had a nice ring to it because, after emigrating to America in 1902, he wrote The Greenhorn Girl, The Greenhorn Boy, The Greenhorn Wife, and The Greenhorn Actor. Rakov wrote dozens of melodramas for the top Yiddish theatre stars, including Bessie and Boris Thomashefsky and Bertha Kalich. Having written a new play, Rakov had a novel sales technique. He would act out all the characters, often crying real tears. The actors around him would cry along and the star and theatre manager would be so impressed they’d buy the manuscript on the spot. Eccentricity seems to run through Rakov’s life. In his last years in Mount Vernon, he kept two huge dogs at home, ensuring that almost nobody from the Yiddish theatre community came to visit. He also called one son Alexander Daudet Rakov after the French novelist. Freakily, the boy became an American novelist called Alec Rackowe. So, not just eccentric, but psychic.

Goldie Lubritsky and Samuel Goldenberg in an unidentified production. Image courtesy The Museum of the City of New York.

7. The Lubritskys

Yiddish theatre was awash with family troupes. There were famous ones like the Kaminskis, the Kompanyetzes, the Treitlers, and the Adlers. And less famous ones like the amazing mishpokhe Lubritsky. There was dad: Isaac-Yankl, a wedding entertainer from Vishegrod in Poland who continued in this line of work in London, adding on jobs as a comic songwriter and theatre prompter. And then there were his three precocious children: Golda, Dave, and Fanny. The Lubritskys were in London by 1896, the year of Fanny’s birth. They all started their careers as child actors on the Yiddish stage, before the family swapped Whitechapel for Brooklyn in 1908. Remarkably, all three children continued to work as professional Yiddish actors in America. Fanny had a successful career in Yiddish musicals, Golda married the Yiddish actor Irving Grossman and toured together with him, and Dave and Fanny both returned to London in Ludwig Satz’s company, which played at the Whitechapel Pavilion Theatre in 1930.

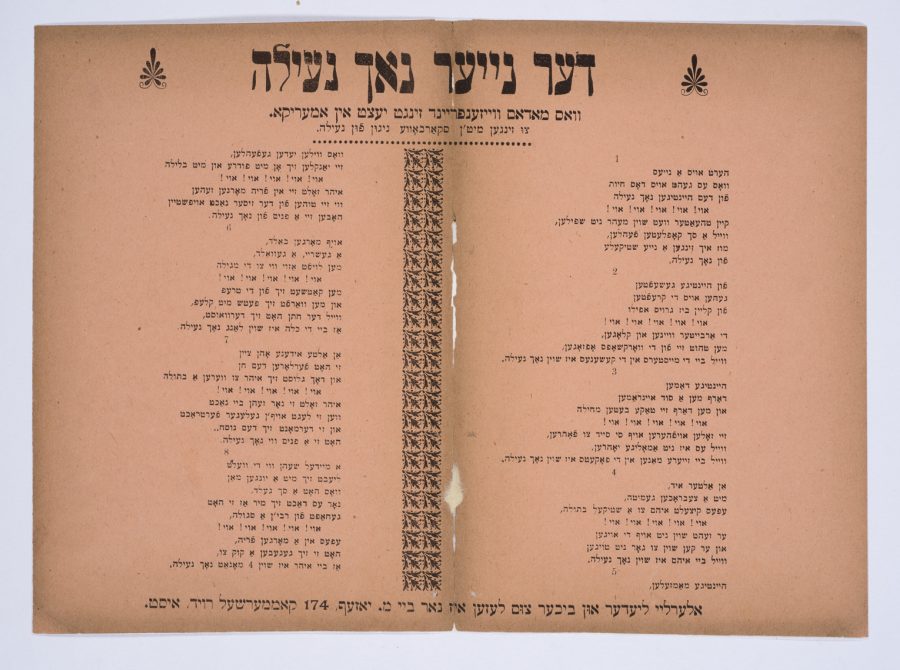

London Yiddish music hall song-sheet c. 1903 featuring lyrics “which Madame Sally Weisenfreund is singing now in America.”

8. The Weisenfreunds

Hollywood legend Paul Muni was one of Warner Brother’s hottest properties in the 1930s and 40s, marketed as “the screen’s greatest actor.” Less well-known was his start in the theatre – as a young kid named Meshulim Meyer Vayznfraynt, bumping over country roads around Lemberg and Krakow in a horse and cart with his parents’ travelling Yiddish song-and-dance show. “Moony” played Yiddish character parts as a kid, showing a startling talent for make-up. The family stopped off in London around 1899. Parents Sally and Philip put on Yiddish music hall shows above a pub behind the London Hospital on Whitechapel Road, while Moony and his brothers went to the Jews’ Free School nearby. All was going fine until rival Jewish gangs started brawling outside the pub, knives and broken beer glasses at the ready. A murder in 1902 saw several of the ringleaders deported. The Weisenfreunds decided they’d had enough of stepping over corpses on the way to work and headed to the US. Muni Weisenfreund became Paul Muni, star of Yiddish theatre, Broadway, and finally Hollywood.

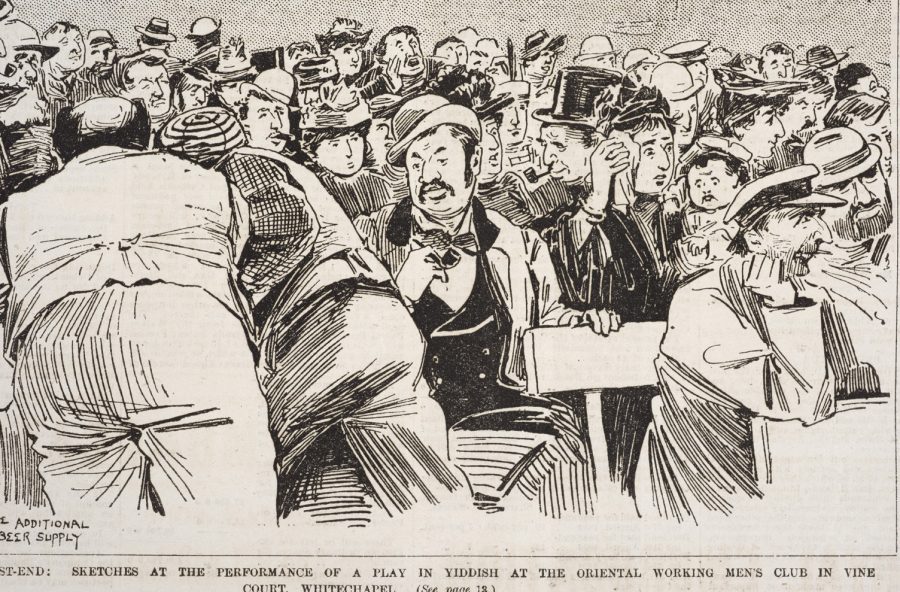

Artist’s sketch of the audience watching a Yiddish performance at the Oriental Working Men’s Club in Vine Court, Whitechapel, c. 1890.

9. Eliyohu Zalmen Yarikhovski (? - ?)

Yiddish theatre composer Eliyohu Zalmen Yarikhovski made his way to London from Warsaw in the footsteps of his younger brother, Yudl (known in London as “Flash”), in the 1880s. Their domain was the Vine Court Hall, a tightly-packed 300-seat fire hazard of a venue down a dark alley off Whitechapel Road. Vine Court was the scene of a brutal murder in the 1880s. Improbably, it was also where Yarikhovski staged his (world premiere?) Yiddish translation of Verdi’s La Traviata in 1889. Yarikhovski surfaces next in Philadelphia, where he seems to have spent many years as music director of the prominent Arch Street Theatre in its Yiddish period. What else did he do in America? Did he leave any surviving trace of his activity in the US? Did he change his name? When did he die? All my inquiries have drawn a blank. EZY (“Easy”) could not have staged his disappearance more effectively if the mafia themselves had ordered it. His is easily the best vanishing act in Yiddish theatre history. This too is a shande far di yidn.

10. Yetta Schoengold (1884 - 1967)

Yetta Schoengold had a successful career in America and Europe but her origins were pure Yiddisher Cockney. Her Polish-Jewish father Marks Rubinstein was an East End purse manufacturer, as well as the manager of a Jewish immigrant club that featured Yiddish plays. Yetta was born in London in 1884. She left school and went into her father’s business, then became a Yiddish music hall singer. You can get an idea of her style on the 1905 London recording of “Gevald, gevald police” (Help, Help Police), reissued in 2003 on the compilation Di Eybike Mame —The Eternal Mother: Women in Yiddish Theater and Popular Song 1905-1929. As Nina Warnke observes, “it will stick in your ear whether you like it or not.” Around 1907, Yetta married the Yiddish actor Bernard Schoengold and settled in New York. Along with other popular Jewish-American actors, she appeared in Spring Song on Broadway in 1934. She died in the US in 1967.

Acknowledgements:

My thanks to Avrohom Lichtenbaum of Fundación IWO, Buenos Aires and Miryem-Khaye Siegel of the New York Public Library for their help tracing some of the images. Nachman Falbel kindly let me reproduce posters from his collection, featured in his 2013 book Estrelas Errantes: Memória do Teatro Ídiche no Brasil (Wandering Stars: A History of the Yiddish Theatre in Brazil).