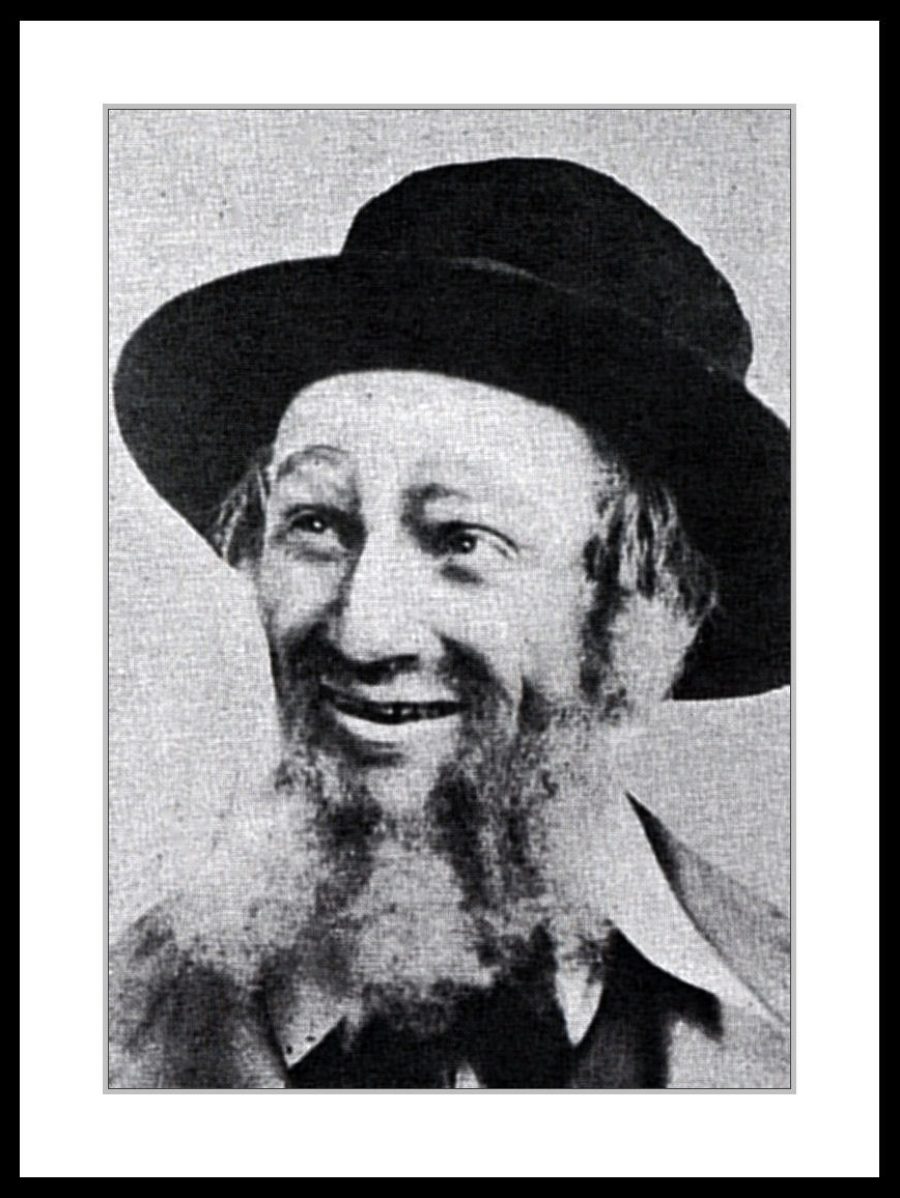

Baruch and Sidney Lumet on the set of The Pawnbroker, 1964

Advice from Sidney Lumet’s Yiddish Actor Dad

Debra Caplan

Here are some things you might already know about the famous American film director Sidney Lumet:

He was a legendary director whose films included the now-classic 12 Angry Men, Seripco, Dog Day Afternoon, The Verdict, The Pawnbroker, and Network, among others. His films were nominated for 40 Academy Awards but he never won an Oscar for directing (when the Academy presented him with an honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 2005, the ever-feisty Lumet told reporters, “I wanted one, damn it, and I felt I deserved one”). He inspired Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor to pursue a career in law. He wasn’t very good at staying married. He once quipped that when he died he wanted his ashes scattered over the famous Lower East Side hangout Katz’s Delicatessen.

Now here are some things I bet you didn’t now about Sidney Lumet:

He was a child actor in the Yiddish theatre. His father, Baruch Lumet, was a Yiddish theatre star who was briefly a member of the famous Vilna Troupe, before he got into trouble with the law and ran away to America; en route, he nearly had an affair with a nun (more on that later).

Sidney Lumet (L) with his father (R) in an unknown Yiddish stage production.

On stage and on screen, Sidney and Baruch Lumet were great collaborators. Each helped the other in his career: Baruch schmoozed with other entertainers in cafes and got young Sidney his first Broadway auditions; Sidney, in turn, helped his aging father with a heavy Yiddish accent get cast in several mainstream American films after his Yiddish theatre career dried up – perhaps most bizarrely as a Rabbi who is also a bondage fetishist in Woody Allen’s Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask.

Baruch and Sidney Lumet on the set of The Pawnbroker, 1964

Offstage and offscreen, they were a father and a son who owed each other everything and yet drove each other crazy. In interviews after Sidney’s rise to fame, Baruch openly told interviewers that he was very disappointed when his wife became pregnant with Sidney, and that he hired someone to abort the pregnancy but it didn’t work. “What do you think of that? I didn’t want him, we didn’t want him.”

Sidney, in turn, told reporters that his father was “a terrible man” who was only likable when he was on stage. Only his talent redeemed him in his son’s eyes: “Nothing admirable about him, until he went to work,” Sidney told Rolling Stone in a 2008 interview. “And then he was admirable.” Offstage, he might not have been the best father, but onstage – he was the perfect father-figure that young Sidney was searching for.

So, who was this Baruch Lumet? Deadbeat father? Yiddish actor extraordinaire? Sidney Lumet’s inspiration, or his greatest fear? And what did he pass down to his son, other than a love for the magic that actors can create and a brewing mistrust of what might lie beneath the ruse?

Baruch Lumet (1898-1992) — who went by the nickname “Bulu” — was a man with with a colorful life that his son could have easily made into a Hollywood movie (the closest Sidney Lumet came to immortalizing his struggles with his father in film was perhaps the final scene in his last feature film, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead). Born in 1898 outside of Warsaw, the elder Lumet became a child actor on the Yiddish stage at the age of six after his father died. Ostensibly, he was employed as a tailor’s apprentice, but he snuck out of work constantly to spend time watching rehearsals in the the theatre around the corner.

To a young boy who had never encountered the arts before, theatre was magical. “And then the scene changed to another place!” he marveled upon seeing his first scene changes, “I mean, my God, how can they do it? Everything was like magic to me.”

Theatre and music became his obsession. For months he saved all of his earnings to buy a piano for his house; never mind that he lived on the second floor and the building wasn’t stabile enough to support a piano. Bulu learned to play the piano outside underneath a tree, while neighborhood kids threw rocks onto the soundboard.

As the First World War raged, Bulu went to Polish drama school, got a theatrical education, and made friends with other young Jews eager to join the Yiddish stage. Eventually, they ended up joining the Vilna Troupe for a few months — until Bulu was captured after rehearsal and forced to dig trenches around Warsaw, in case the Bolsheviks returned. A few weeks later, a friend advised him that he was in trouble for his political activities and that he ought to disappear — and without a word to his castmates, wife, or month-old baby, he fled to America.

Between Germany and London, Bulu met a beautiful nun who saved him from having his passport confiscated by the authorities.

In comes a very fancy lady, very tall and beautiful. A sister with a white hat, you know, the pointed hat. A nun. Blue, beautiful blue coat. Packed, a lot of people, and she didn’t have a … I start to move and made room for her. […] Finally through the night, little by little she got more comfortable…and I felt her head is leaning against…on my shoulder. Before she fell asleep she took the quilt, covered my thighs and her thighs, you know, to keep warm and her hands were very cozy. And we rode the whole night.

It was a short-lived love affair: the nun wanted to marry him in order to get a visa to come to America, but according to Bulu’s retelling, he suddenly remembered his wife and child and refused to bring her.

After a year or two working as a piano salesman in New York, Baruch Lumet was able to bring his mother, wife, and infant daughter Fay to America. It was around this time that Bulu met the infamous Maurice Schwartz, who offered him a contract at the Yiddish Art Theatre over lunch (when Bulu insisted on a legally-binding paper contract, Schwartz reportedly scrawled out a few lines on the corner of a bag full of grapes). “He was such a mamzer (bastard),” Bulu would later say, but “he could get anything he wanted from anybody.”

Just at the moment when a career on the American Yiddish stage was finally within his reach, Baruch learned that his wife was pregnant with a son. He paid $50 for his wife to have an abortion at home, but to their surprise it didn’t work. And Sidney Lumet was born.

As Sidney grew, Bulu realized that his son had a talent for acting. He began to invite Sidney to perform alongside him - first in Yiddish radio shows, then on the Yiddish stage.

Baruch Lumet as the Zeyde of Brownsville in his hit radio and stage play of the same title. Sidney Lumet played his grandson.

He talked friends on Broadway into giving Sidney auditions for children’s roles, and co-acted with his son in The Eternal Road directed by Max Reinhardt and composed by Kurt Weill.

Bulu may have not been planning on having a son, but in the end, he was proud of his achievements (and even claimed some of them as his own).

When he became a director, I told him, ‘Sidney, remember one thing, the most important thing a director has to think about are his actors. Love the actors even if you hate the script.

Sidney Lumet may have had a love-hate relationship with his dad, but he learned this lesson well and became an “actor’s director” through and through.

Photos of Sidney and Baruch Lumet are from the Archive of the National Center for Jewish Film. Baruch Lumet quotes are from an oral history conducted by Anita Wincelberg in December 1976 for the William E. Wiener Oral History Library of the American Jewish Committee at New York Public Library. Full transcript of the interview.