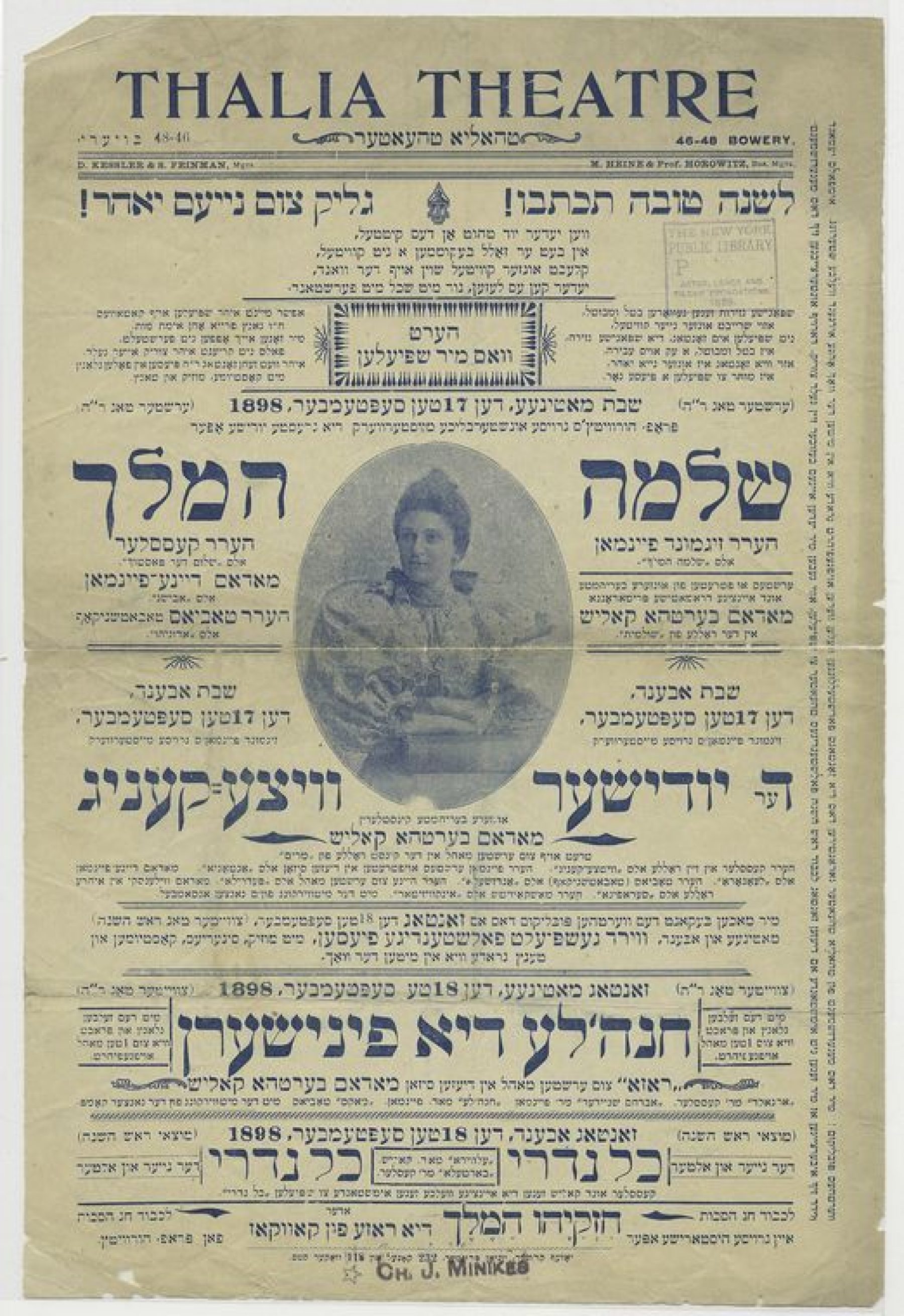

Playbill of the Thalia Theater with the matinee and evening program for Rosh Hashanah September 1898, including Sharkansky's opera Kol Nidre. NYPL Digital Collections: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-db69-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Something Special for the High Holidays

Judith Thissen

In the dynamic setting of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the Yiddish stage gained a popularity that was unparalleled in Jewish history. For several decades, the Yiddish theatres on the Bowery and Second Avenue gave immigrant Jews and their children a sense of belonging that went beyond everyday attachments to family, friends, landslayt, and co-workers. Jewish holidays in particular were singled out for a collective affirmation of ethnic bonds. During Sukkot and Pesach thousands went to the Bowery for special performances promoted as lekoved sukes (in honor of Sukkot) or lekoved peysekh (in honor of Passover). In the early 1900s, these two holidays marked, respectively, the beginning and the end of the high season in the Yiddish theatre district. Theatregoing during the High Holidays was less frequent, although extra matinees were often scheduled on the first and second day of Rosh Hashanah or for the end of Yom Kippur. However, on these red-letter days, many immigrants went to the Yiddish playhouses for a very different type of “show.”

The shortage of synagogues in turn-of-the century New York City created a quite unique mixture of religious observance and entertainment, faith, and trade. Each year, several Yiddish playhouses and many more movie theatres were turned into provisional synagogues to accommodate those immigrants who were not affiliated with a congregation, but still wanted to worship during the holidays (so-called “Yom Kippur Jews”). As the season came, the demand for seats outstripped the existing capacity and “mushroom synagogues” filled the gap, especially in working-class Jewish neighborhoods, where synagogues were typically small and only the largest congregations maintained their own buildings. Most of these services were for-profit enterprises for which one had to buy a ticket in advance. A 1917 survey counted 343 temporary synagogues with a total seating capacity of 163,638. The majority of these prayers services took place in public meeting halls. Theatres ranked second. A total of fifty-nine moving-picture theatres and nine legitimate playhouses were turned into synagogues. Although using theatres for religious services was not specifically an American invention, as we know from Bertha Kalich’s memoirs and what happened in Paris at Théâtre Lancry, the phenomenon was nowhere as widespread as in New York City.

Not surprisingly, there was quite a bit of resistance to these temporary synagogues. In the view of the New York Kehillah, it was a “desecration” and “public disgrace” that prayer services were held in such “unholy places” as theatres, moving-picture houses and dance halls. “Warned of Fake Synagogues: Jewish Community asks Jews to avoid mushroom congregations,” reported the New York Times in August 1909, a few weeks before the beginning of the holiday season. The conservative Yiddish newspapers, for their part, sought to discourage the commercial prayer services by circulating stories that emphasized their shady character. Thus we learn that in 1912, a crowd of people waited in vain in front of Max Gabel’s Comedy Theatre for the cantor to arrive for the Rosh Hashanah service, but he did not show up because of disappointing ticket sales. Gabel apparently managed to calm the outraged crowd by distributing free tickets for his evening show. In another instance, reported by the Morgen Zhurnal, the evening prayers of Yom Kippur were interrupted by the moving-picture manager, who warned the cantor to “hurry up” because a crowd was waiting outside for the picture show that would start after sundown. Such sensational stories had little effect. The practice continued until the early 1930s, when New York State legislation put an end to the commercial exploitation of prayer services.

Clearly, many New York Jews did not see any harm in the economic exploitation of the High Holidays and eagerly bought tickets for commercially-organized prayer services. In fact, they may well have considered celebrating the High Holidays in a Yiddish theatre or moving-picture house far more attractive than going to a regular immigrant synagogue, as many congregations convened in tenements and other small, makeshift places of worship. In his memoir about growing up in Jewish working-class Brownsville (Brooklyn), Alfred Kazin draws a colorful picture of the contrast between the immigrant synagogue where his family celebrated the High Holidays and the movie theatre of his youth. It was a small, rundown makeshift synagogue, he writes, “which had a permanent stale smell” of snuff, old books, dusty velvet and food. Across the street was the real sanctuary of his childhood, the large Stadium Theatre (102 Chester Street), “the great dark place of all my dream life,” where he went every Saturday afternoon.

That poor worn synagogue could never in my affections compete with that movie house, whose very lounge looked and smelled to me like an Oriental temple. It had Persian rugs, and was marvelously half-lit at all hours of the day…

Alfred Kazin, A Walker in the City (1951)

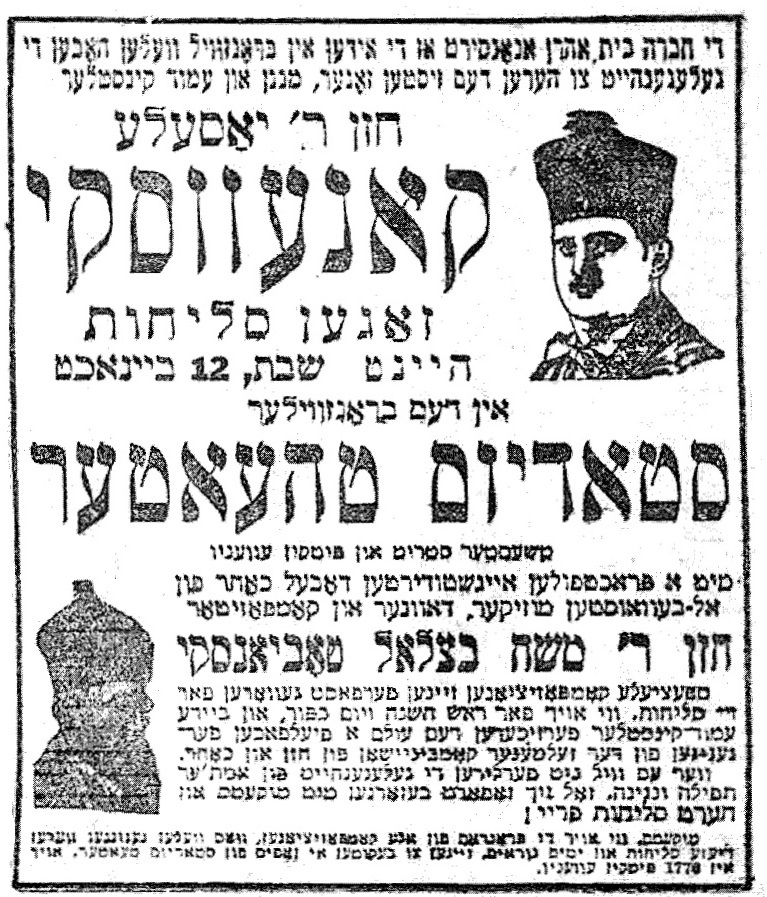

The Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services in the large Yiddish playhouses represented the high end of the market. Ticket prices for these widely-advertised showy events ran from fifty cents to two dollars. They featured star cantors who were accompanied by the theatre’s orchestra and chorus. For all parties, it was a lucrative business. When Jacob Adler subleased the Grand Theatre to A.L. Woods, the contract explicitly mentioned that he kept the “exclusive possession and use” of the playhouse on the Jewish New Year and Yom Kippur from sundown to sundown. Entrepreneurs who rented the theatres to set up temporary synagogues typically promoted the aesthetic quality of the location. For instance, in 1905, a newspaper ad for holiday services at the People’s Theatre on the Bowery boasted: “Do you want to get pleasure for your money this year? Then come to the beautiful, airy People’s Theatre Synagogue. You will hear good singing, beautiful davening [praying], Jewish and sweet.” And a few years later, the organizer of Rosh Hashanah services at the Bronx Casino promised “the best seats for the best prices” and emphasized that the place was “big, airy and well-lit and you will be comfortable.”

In her research on the religious life of Jewish immigrants, Annie Poland points out that many established congregations in New York City engaged in the same business practices as the temporary synagogues. In their desire to sell as many seats as possible to non-members, the marketing strategies of the congregations often emulated the “American bluff” of the entertainment industry. In 1912, the conservative Morgen Zhurnal noted with dismay that most synagogues on the Lower East Side were covered “from the roof to the basement” with “posters, playbills, advertisements, handbills, circulars and announcement” that promoted the qualities of the congregation’s cantor and choir. In one poster, the voice of one cantor was hailed as “five hundred times stronger and sweeter than Caruso’s.” Another promoted a “world-renowned” cantor with a voice that sounded like “fifty canaries.” The newspaper complained that many prayer leaders were “more showmen than cantors.”

High Holiday Services with Chazan Kanivesky at the Stadium Theatre (Brooklyn), Jewish Daily Forward, September 1, 1923.

High Holiday Services at Kessler Second Avenue Theatre, Jewish Daily Forward, September 1, 1923.

High Holiday Services at Kessler Second Avenue Theatre, Jewish Daily Forward, September 8, 1923

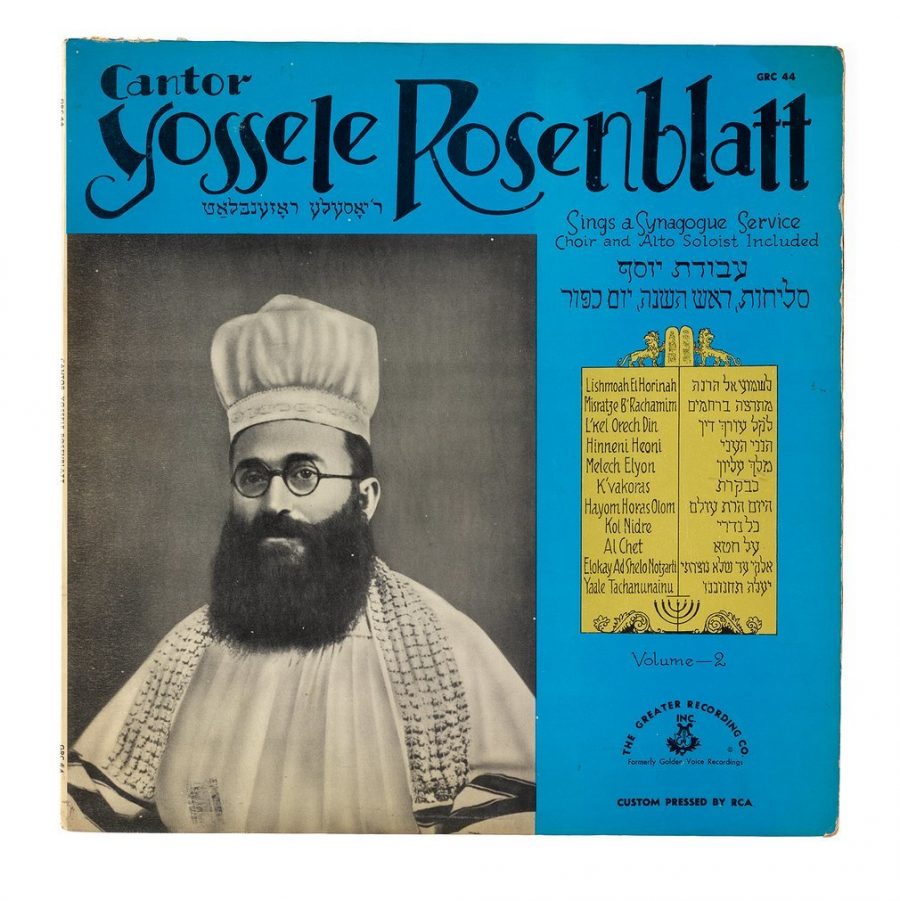

In the 1920s, economic prosperity, the explosive growth of the record business and the breakthrough of radio accelerated the commercialization of the High Holidays. Cantors became as popular as Yiddish theatre stars. In 1927, Yossele Rosenblatt, America’s most famous chazzan, allegedly received $15,000 for three days of prayer during the High Holidays. To give some idea of the huge amount of money this represented: in New York a skilled garment worker earned $2 per hour at best in those days, but a coat presser not more than 25 cents. Rosenblatt’s performances were popular with Jews as well as Gentiles. He toured the American vaudeville circuit and made dozens of recordings – from Kol Nidre to Mayn yiddishe mame. He was not the only cantor who embraced new media to reach a broad audience. Pathé Records boasted that “every prayer that is sung in synagogue on the holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur can be found on our list, and our Jewish patrons will have the greatest pleasure on hearing the following records by the greatest and most famous cantors in New York.”

Congregations and providers of commercial prayer services adapted to the changing taste of the audience and the growing competition from radio and records. Traditional lamentations got out of fashion. A newly-appointed cantor was warned not to whimper as his predecessor did: “Why cry so much?” To survive on a market governed by the law of supply and demand, cantors and choir leaders included Yiddish theatre tunes, motifs from Italian operas, and Tin Pan Alley melodies in the High Holiday services. According to the Forward, worshippers appreciated this “well merited entertainment after the long tedious stretches of wailing and whining.”

Cantor Yossele Rosenblatt Sings a Synagogue Service. Recorded by RCA.

In the Yiddish theatre business, Rosh Hashanah superseded Sukkot in importance. From the early 1920s onwards, the holiday often marked the opening of the new season. The special “shana tova” matinees and evening programs were heavily promoted in the Yiddish press. It seems that a theatre outing after the closing of Yom Kippur was a little more difficult to sell to the older Yiddish-speaking generation because tickets were frequently offered at bargain prices. There was also more competition–and not only from prayer services with star cantors. Broadway had discovered the emerging market of upwardly-mobile Jewish holidaymakers who were looking for a more American High Holiday experience.

Immigrant Jews had long been ignored by the upper segments of the American entertainment industry and relegated to the nickel-and-dime business of neighborhood movie theatres. This changed in the late 1910s, when showmen like Samuel ‘Roxy’ Rothafel, Marcus Loew, and the Shubert Brothers realized that more and more Eastern European Jews were abandoning the Yiddish theatre and East Side picture shows for Broadway picture palaces and high-class vaudeville houses. To create customer loyalty, they introduced special Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur matinees and included Jewish acts and songs into the program around both holidays. Although only a minor part of the bill, which typically consisted of a live show followed by a feature film, it was a meaningful gesture towards their growing Jewish clientele and indeed much appreciated.

The observance of Rosh Hashanah, which began at sundown last Monday night has its counterpart in a portion of the music program of the Capitol Theatre. William Robyn, popular lyric tenor, sings ‘Kol Nidre,’ the ancient Hebrew invocation, accompanied by the Capitol Grand Orchestra.

American Hebrew, September 14, 1923.

At the 5,500-seat Capitol Theatre, the largest picture palace on Broadway, the performance of Kol Nidre became a standard feature of the program during the High Holiday season. Another hit for the occasion was ‘Eyli, eyli’ (My God, My God) – originally a Yiddish theatre song from the late 1890s, which had been popularized by Jewish vaudeville star Belle Baker.

Sheet music cover Eli-Eli with Belle Baker (Kammen publications, 1937). Photo source: Dan Wyman Books.

There is little information about these special attractions targeted at Jewish audiences. The acts were rarely announced in newspaper advertisements, so people must have known about it – a sort of tacit knowledge. Sometimes we get a glimpse of what was happening on the stage and in the auditorium from reviews in the American trade press. From a report in Variety we know, for instance, that William Robyn performed Kol Nidre in “a sort of pulpit in front of a star cloth with a light effect suggesting rays coming through a temple window.” In 1927, Alan Crosland would use a very similar setting for Yossele Rosenblatt’s performance in The Jazz Singer, Hollywood’s first feature-length talkie and a huge box-office success with New York Jews. In both cases, the scenography temporarily transforms the secular setting of the stage into a pseudo-sacred space.

Music hall scene with Yossele Rosenblatt, The Jazz Singer. Warner Bros., 1927.

High Holiday attractions on Broadway and in other upscale entertainment districts were very popular. Throughout the 1920s and with ever more enthusiasm, Variety reported “excellent takings,” “standees in all aisles,” and “unexpected matinee business” during Rosh Hashanah and at the close of Yom Kippur. The effects of the Jewish holiday trade on the box-office were substantial not only in New York City, but in Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Newark, and Boston. In the context of Jazz Age prosperity and modernity, Jewish holidays had become big business well beyond the Yiddish theatre and the immigrant milieu of the Lower East Side.