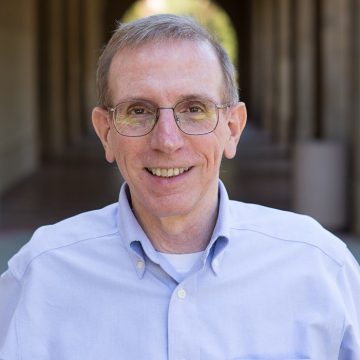

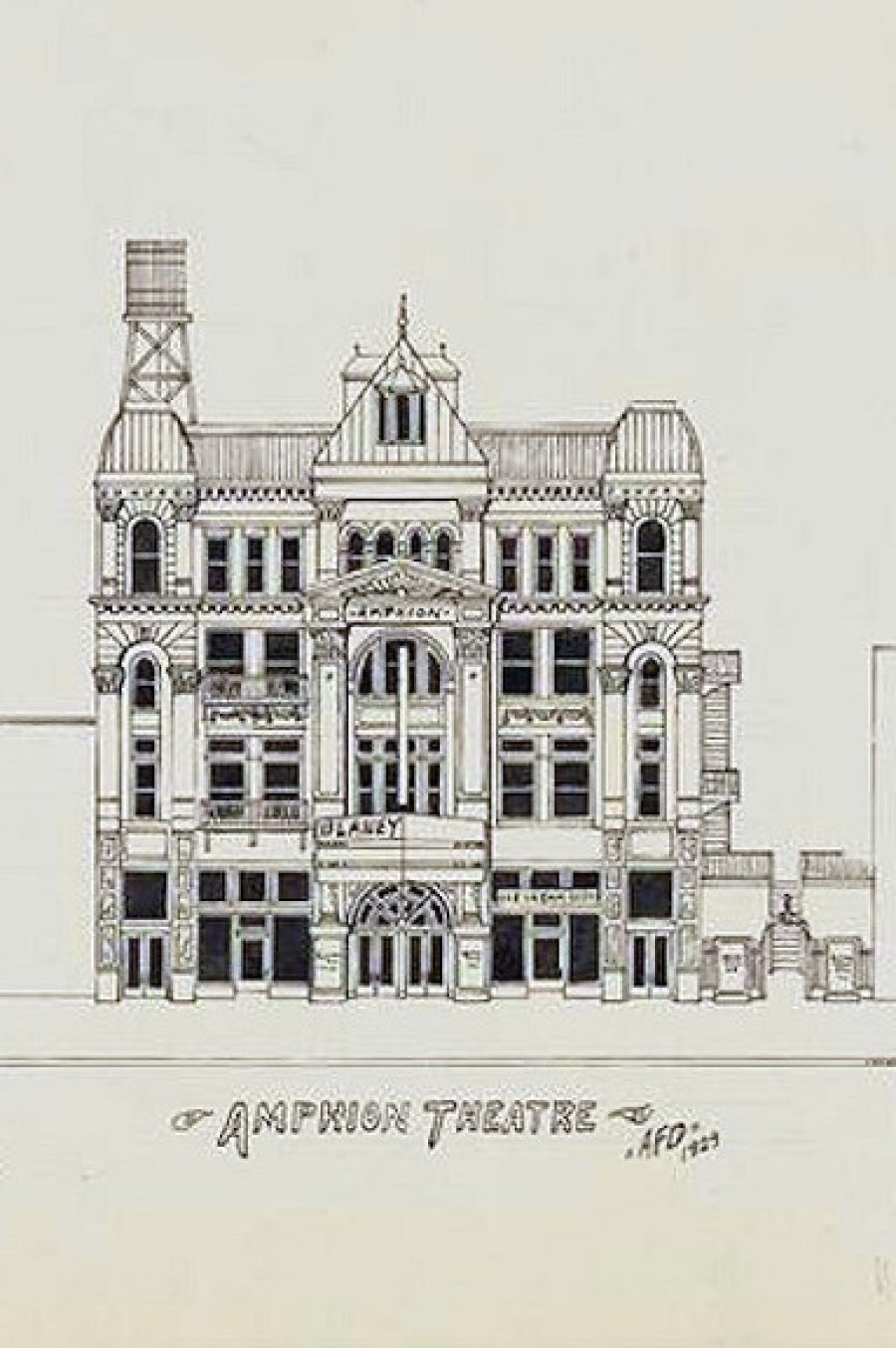

The Amphion Theatre’s artistic partners, 1925-1926. Source: https://www.museumoffamilyhistory.com/brooklyn/yt/amphion/dybbuk.htm.

Khonen in Drag: Cross-Dressing in Two Productions of The Dybbuk during the 1920s (Plus, a Review of One of These Productions)

Zachary Baker

Translator’s introduction

The “trouser role,” in which a female performer plays an ostensibly male character, was not unheard of in the Yiddish theatre, especially in connection with light entertainment fare. Prominent female stars who are remembered for their cross-dressing roles include Bessie Thomashefsky, Pepi Litman, Nellie Casman, and, of course, Molly Picon. (In addition, girls were sometimes called upon to play young boys.) However, it was quite unusual for a woman to play a man’s part in a serious Yiddish drama.

Sh. An-sky’s famous drama Tsvishn tsvey veltn, oder Der dibek (Between Two Worlds, or The Dybbuk) is about as serious as it gets. Central to its plot are the encounters in the first act between the orphaned yeshiva student Khonen and Leah, daughter of the wealthy Reb Sender Brinnitzer. They sense a mutual attraction, unaware that their fathers, Nisn and Sender, had pledged them to each other before they were even born. But Reb Sender chooses to ignore auguries that the now-impoverished student Khonen is his deceased friend’s son, and instead chooses to marry off Leah to the scion of a wealthy family. After Khonen dies in a fit of kabbalistic self-mortification, his disembodied spirit—a dybbuk—enters Leah’s body and refuses to depart. The play’s action and dénouement in the succeeding acts proceeds from there. Although Khonen as a flesh-and-blood character appears only in the first act, he is absolutely essential to the plot. Without Khonen there is no Dybbuk.

The role of Khonen was almost always assigned to a male actor in productions of The Dybbuk. The Vilna Troupe gave the play its premiere in Warsaw on December 9 1 , 1920, with Alexander (Alyosha) Stein as Khonen and Miriam Orleska as Leah. For the play’s U.S. premiere in 1921, Maurice Schwartz played Khonen opposite Celia Adler’s Leah at New York’s Yiddish Art Theatre. (In Act 3 of that same production Schwartz also played Reb Azrielke, who carries out the exorcism that banishes the dybbuk from Leah’s body [!].) 2 In the Vilna Troupe’s touring production in New York in 1924, Alexander Asro played Khonen opposite Sonia Alomis as Leah. And of course, in the 1937 Polish Yiddish film version of The Dybbuk, we see Leon Liebgold opposite Lili Liliana.

And then there was the play’s production at the Amphion Theatre, a relatively obscure venue on Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where for the 1925-1926 season Samuel Goldenberg served as the director, with Celia Adler as his co-star and artistic partner. Their staging of The Dybbuk, in November 1925, caught the eye of Leon Crystal, an editor at the Yiddish daily Forverts who moonlighted as theatre critic for the anarchist weekly Fraye arbayter shtime. Crystal had not originally intended to write a full-dress review of the Amphion’s Dybbuk, but he was so taken by the production that he felt driven to do it justice. The Amphion, as a “neighborhood theatre,” was off the beaten track and its productions infrequently attracted the attentions of the critics. 3

In his review, Crystal refreshed readers’ memories by pointing out that Celia Adler had played Leah at the Yiddish Art Theatre in 1921 and was now reprising the role at the Amphion. Elye Tenenholtz, who had played one of the synagogue idlers (batlonim) in the Art Theatre’s production, was the Amphion troupe’s Messenger (Meshulekh), and several of the other actors had also appeared in the Yiddish Art Theatre’s Dybbuk. Goldenberg—who was not a member of the Yiddish Art Theatre’s company—played Reb Azrielke. Crystal praised them and the other performers, with the notable exception of the comic actor Irving Jacobson.

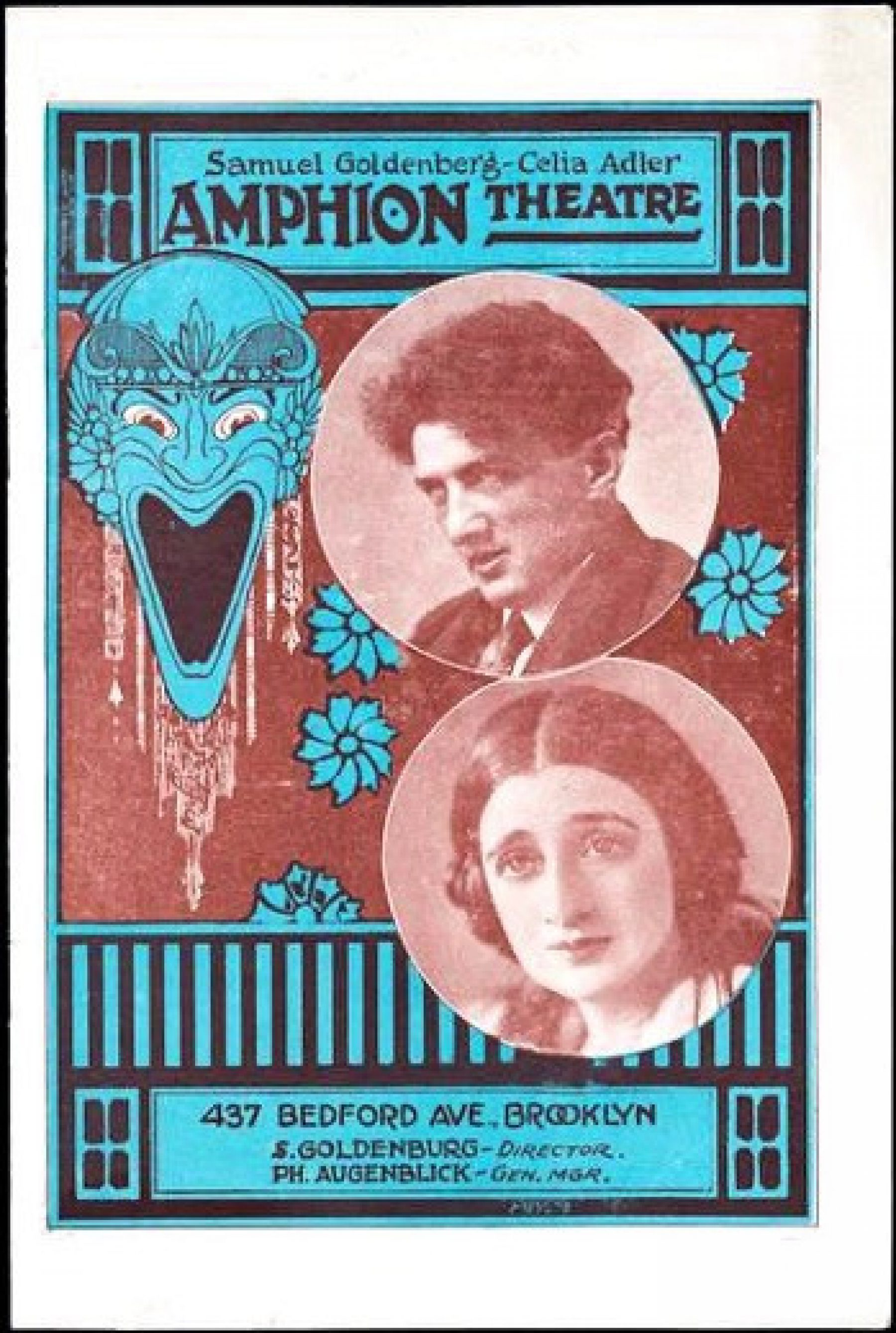

The Amphion Theatre’s offerings for the week of December 22, 1925. From top to bottom: The Dybbuk by Sh. An-sky; The Living Corpse, by Leo Tolstoy; Shulamis by Abraham Goldfaden; and the season’s “greatest success,” the operetta Kinder-libe (Love of Children) by Joseph Brody and Louis Freiman, with lyrics by Joseph Tanzman, choreography by Dan Dowdy, and a twenty-four-member chorus. Ad from the Forverts, December 22, 1925.

Well past the review’s midpoint, Crystal remarked, almost as an aside, that Khonen—Leah’s predestined groom, her basherter—was played by a woman, Chana Spector. Moreover, in Crystal’s judgment Ms. Spector performed the role “astoundingly” well, even if he found her “feminine figure” difficult to disguise. He mentioned her gender merely as a fact and did not speculate as to the thinking behind this unusual casting choice.

Crystal knew The Dybbuk inside-out; he had been the Yiddish Art Theatre’s business manager when that company staged the play back in 1921, before he became a journalist. Later, in early 1924, he also saw the Vilna Troupe’s touring production of The Dybbuk. Those two productions provided the baselines for his analysis of the Amphion Theatre’s production. He observed that the Amphion’s staging owed more to Dovid Herman’s symbolist interpretation with the Vilna Troupe than to Schwartz’s somewhat more realistic approach. (Crystal’s boss at the Forverts, Abraham Cahan, offered a considerably blunter appraisal of those earlier productions: “In comparison with Herman’s Dybbuk, as performed by the Vilna Troupe, [Schwartz’s] was prose as compared with poetry.” 4 )

In his review, however, Crystal neglected to mention a third, highly celebrated production of The Dybbuk: the Hebrew-language Habima company’s powerful and iconic staging in Moscow, in January 1922. It was directed by Yevgeny Vakhtangov, with Natan Altman’s stark and eye-catching sets. An avant-garde disciple of Konstantin Stanislavsky, Vakhtangov was one of Russia’s leading theoreticians of theatrical performance.

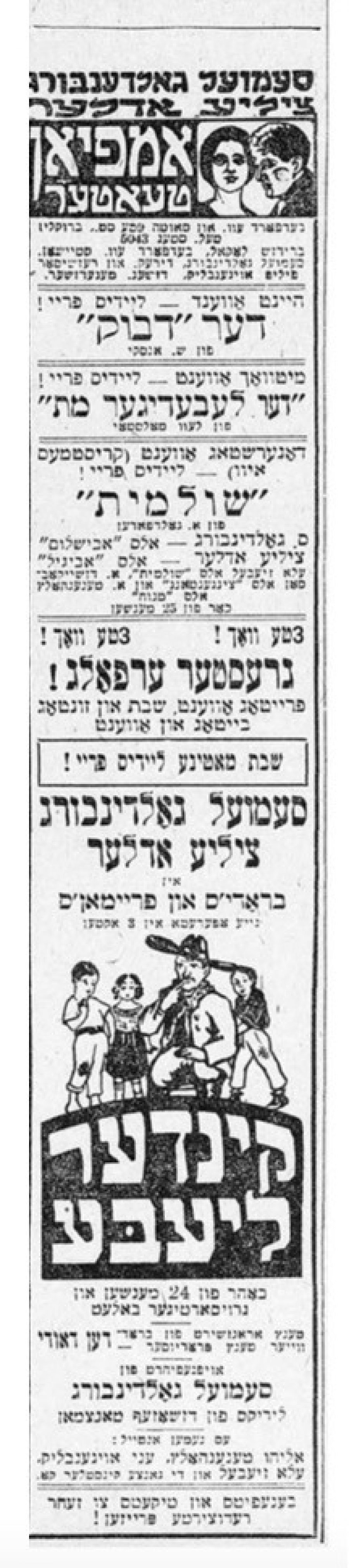

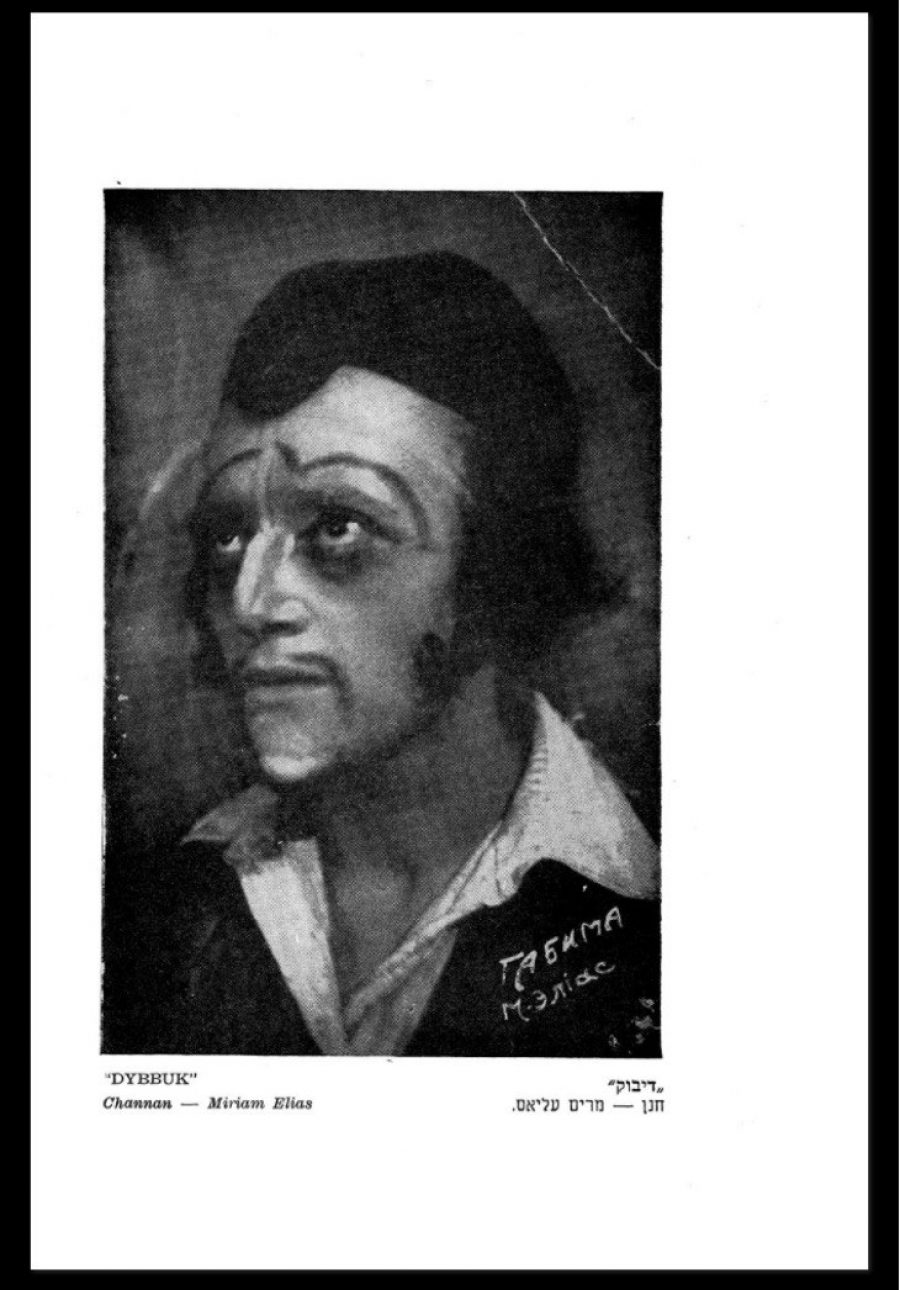

Leon Crystal would certainly have been aware of the Habima production, as would Goldenberg and Adler, even though none of them had yet seen it. And it was precisely that production which provided the precedent and the model for casting a woman as Khonen, with Vakhtangov placing Miriam Elias in the role opposite Hanna Rovina as Leah. 5 A fellow member of the Habima troupe, Chayele Grober, wrote that Elias possessed “many of the attributes of a man; her height and broad shoulders surpassed the figure of a woman; her voice was deep and strong; her gait was broad and confident; her motions—highly masculine.” 6 These physical qualities, combined with her excellent knowledge of Hebrew, made her well suited to the role.

According to the Russian director and theatre scholar Andrei Malaev-Babel, Vakhtangov envisaged Khonen “as a pure spirit, already a living ghost at the start of the play. His entire being was filled with unearthly love for Leah, and with the striving to restore justice through the mysterious power of the Kabbalah.” 7 Theatre historian Ruthie Abelovich writes (citing the Israeli scholar Yair Lipshitz), “The casting of a female to play the role of Ḥanan is a prefiguration of one of the dominant attributes of the dybbuk: a masculine presence within a female body.” 8 Naomi Seidman characterizes An-sky’s play as an “exploration of the inextricability of tradition and modernity in a sexual dialectic, one based on the symbiosis of homoerotic and heteroerotic love…. In the dybbuk heterosexual passion, taken to its logical extreme, produces a kind of drag, in which a man wears not women’s clothing but her very body.” 9 Vakhtangov appears to have understood this implicitly; Elias’s makeup and costume conformed to Habima’s expressionist staging while also accentuating the yeshiva lad’s androgyny.

Malaev-Babel stresses the importance for Vakhtangov of the “archetypal gesture,” which represents “life at its quintessential.” In addition to its theoretical justifications, the function of gesture was absolutely critical toward overcoming the language barrier for Habima’s audiences in Moscow and “in The Dybbuk, Vakhtangov fulfilled the task of discovering a universal theatrical language.” 10 Toward this end, Miriam Elias “excelled in the role of Khonen,” wrote R. Ben-Ari, an early chronicler of the Habima company. 11 Nick Worrall, a British theatre historian, describes Elias’s performance as “especially effective during the sung moments, where she managed to create the impression that the only realities were love and death.” 12

In 1923, about a year after Habima put on The Dybbuk in Moscow, Elias emigrated to the US, accompanied by her then-husband, the artist and set designer Boris Aronson (they later divorced). For a time, she performed in Yiddish theatres in New York City, including the Yiddish Art Theatre. 13 In fact, she was a member of that ensemble during the 1925-1926 theatre season, when Adler and Goldenberg were at the Amphion across the East River in Brooklyn. By then, it seems likely that Elias would have become personally acquainted with Goldenberg and Adler, and perhaps she compared notes with them concerning Vakhtangov’s Dybbuk production at Habima in Moscow and her role in it as Khonen. Consequently, if we are to enumerate artistic influences on the Amphion’s Dybbuk production, we might also cite Vakhtangov and Habima alongside Leon Crystal’s references to the Vilna Troupe and the Yiddish Art Theatre.

In the absence of documentation beyond Crystal’s review, we cannot know for certain which of the Amphion Theatre’s two principal artistic partners picked the still-unknown Chana Spector to play Khonen, but one need not search far afield to figure out where they found her. For his Dybbuk production at the Yiddish Art Theatre in 1921, Maurice Schwartz had recruited many of the extras and actors playing minor characters from the ranks of the Kunst-ring, an organization of young Yiddish theatre enthusiasts—among them, Chana Spector. Adler would have remembered Spector and that may have been a consideration in recruiting her as Khonen at the Amphion Theatre. 14 In 1925, Spector would have been about twenty-three years old.

In casting a woman for this role, the Amphion’s creative team may have wished on the one hand simply to highlight Khonen’s obvious youth. The timbre of Chana Spector’s voice would have suggested that Khonen—and Leah, too—was merely on the cusp of adolescence when he ended his own life in a moment of frustrated (and frenzied) eroticism. (For her part, playing girls in their early teens was one of Celia Adler’s hallmarks.) Judging from Crystal’s offhand comment about her “feminine figure,” Spector evidently cut a rather different profile on the stage than did Elias, in Moscow. We know nothing about her (or indeed any of the actors’) makeup and costumes. The Amphion production’s sets were probably not terribly lavish, given that the play was put on there for only a few performances.

Miriam Elias in the role of Khonen, at Habima (Moscow), 1922. Source: R. Ben-Ari, Habimah([Chicago: L. M. Stein, 1937).

All the same, in casting Chana Spector as Khonen, Goldenberg and Adler may also have made some of the same calculations as Vakhtangov had, in terms of the play’s complex sexual dynamics. The ambiguity of gender identity was a theme that Goldenberg in particular would explore in a role that came to occupy a central position in his repertory: the androgynous tumtum Morris Green in the melodrama Yo a man, nit a man, which had its premiere in 1927. For Goldenberg, the venturesome casting of Chana Spector at the Amphion Theatre may have represented an early phase in his exploration of that theme.

Unlike some members of her Kunst-ring cohort—Zvee Scooler, for one—Chana Spector did not become a professional Yiddish actor. 15 But neither did she stray from the Yiddish cultural orbit. Rather, Spector became a bona fide Yiddish radio celebrity (as Scooler eventually did, as well). From the 1930s until the early 1950s, she had her own program on New York’s WEVD, “the station that speaks your language.” Her future husband, Oscar Goren, was likewise affiliated with WEVD as a producer and news announcer. Celia Adler described Spector as “one of the first and the best female personalities on Yiddish radio” and wrote with considerable warmth and nostalgia about the solace that she found in the Spector-Gorens’ “beautiful and warm home” during difficult moments in her personal life. It was a place “where the most prominent personalities of the literary and artistic world used to gather.” 16 Alas, both Oscar Goren and Chana Spector died at relatively young ages: he in 1947, only 39, and she in 1952, at the age of 50.

In his review of the Amphion’s production of The Dybbuk, Leon Crystal lamented that the theatre’s unnamed managers (Sam and Philip Augenblick, who had rented the theatre) were unwilling to continue the play’s performances beyond a single long weekend in November 1925. During the succeeding months, though, at least two more brief runs of The Dybbuk took place at the Amphion. Concurrently, in mid-December 1925, an English-language production in Henry G. Alsberg’s translation opened at the Neighborhood Playhouse on Grand Street (its director, David Vardi, was a Habima veteran who had worked alongside Vakhtangov). Then, in short order (January 1926), Maurice Schwartz relaunched his production of the play at the Yiddish Art Theatre, where it ran for weeks on end. (Celia Adler archly remarked that whenever Schwartz ran into financial difficulties, he would put on The Dybbuk in the hopes of rebalancing his company’s books.) And toward the end of 1926 Habima, too, would finally bring its Dybbuk production to New York audiences. During those years, “Dybbuk fever” struck elsewhere across North America as well, with productions in Los Angeles, Chicago, Montreal, and possibly other cities. For the Amphion’s partners to have ventured so ambitious a production at a marginal vinkl-teater constituted “a considerable success,” Adler later recalled. 17 Chana Spector, cross-dressing as Khonen, certainly contributed to that artistic triumph.

Yevgeny Vakhtangov died in May 1922, only four months after his production of The Dybbuk opened in Moscow. Had he lived, one wonders whether he would have continued the practice of casting a woman as Khonen. But after Vakhtangov’s death, male actors played Khonen in the Habima company’s subsequent productions of The Dybbuk. As we have seen, this was also true of the play’s early Yiddish productions. 18 In retrospect, though, it is somewhat surprising that the casting of a woman as Khonen turned out to be such an exceptional circumstance, given how effective both Miriam Elias and Chana Spector were in that role and how well they fit into the hall of mirrors that is An-sky’s Dybbuk.

The Dybbuk at the Amphion Theatre

By L. Krishtal [Leon Krystal]

Fraye arbayter shtime (New York), November 25, 1925

The Dybbuk has leapt onto the stage and doesn’t want to come down. If An-sky’s work hasn’t already run itself into the ground, then at any rate it feels like it just keeps on running year-in-year-out. Yet, The Dybbuk continues to pop up in different countries, in different theatres, and in different productions and interpretations.

An-sky’s dramatization of The Dybbuk legend is stage-worthy material—it casts such a spell that once it’s made its presence felt in the theatre it can’t be resisted. There’s a certain mood in The Dybbuk—the air of Jewish mysticism, ideas, and ethics, the dramatic ceremonials of Jewish ritual, and so on and so forth.

Last Friday, Saturday, and Sunday [November 20-22, 1925], The Dybbuk was staged once again, this time at the Amphion Theatre. For that, [Samuel] Goldenberg and Celia Adler are to be congratulated. How come? It seems to me that they have been amply rewarded both for the pleasure of their acting and for the size of the audience. It’s a bit of a mystery why The Dybbuk won’t remain on the boards there during the profitable weekend days.

And I must confess: I was expecting nothing more than a performance “according to the given circumstances.” (It’s a neighborhood theatre, after all, with two or three different plays being put on each week and no time for rehearsals.) As it turned out, this production is worthwhile not only in relatively terms but on its own merits.

Goldenberg’s production is closer to the Vilna Troupe’s conceptualization than to [Maurice] Schwartz’s. Even so, the director retained a realistic kernel, resulting in a completely healthy combination of the two – while possessing a hint of its own tendencies which, by the way, do not come across all that clearly. (Consider, for example, the shattering of a pane of glass when the dybbuk emerges.) Overall, though, the production is thoroughly successful and powerful, notwithstanding the accursed “circumstances.”

The performance of The Dybbuk at the Amphion Theatre is especially strong from the standpoint of acting. Celia Adler’s Leah, about which there was much to be said when that actress played the same role at the Art Theatre [1921], became if anything more profound and more refined here. The dybbuk-girl’s expression, in Celia Adler’s interpretation, has become more ethereal [fargaystikt] in its nature and it radiates with a more tragic spirit than previously. Celia Adler performs the “pathological” scenes with greater tenderness and more convincingly. In the moments when the dybbuk releases her and she speaks in her own voice (as, for example, when she asks her grandmother, “What do they want to do with me?”) Celia Adler gives Leah the sensation of a tender, distressed baby—or an ailing songbird.

During the past few years Yiddish actors have begun to speak more consciously about plasticity [plastik]. However, many of them don’t know precisely why it is necessary and what purpose it serves while playing a part. Let them take a good look at how Celia Adler, with her entire being, expresses the onslaught of fear while visiting the grave (in Act 2 of The Dybbuk), and the whirlwind of motion with which she drops down when the dybbuk enters her Leah!

In Goldenberg’s Azrielke from Miropol there is an unexpected (to me, at least) mastery of stagecraft. Goldenberg played the Miropoler tsadik after having had the opportunity to see two exemplars: at the Art Theatre and with the Vilna Troupe. That doesn’t always make an actor’s job easier. Departing from a previously established type and achieving something new can sometimes be much more difficult than, from the very beginning, anchoring oneself in one’s own conception—especially when there is not enough time and enough motivation [gemit] to seek out the conception within yourself and give it its own form. Nevertheless, Goldenberg succeeded in that.

His Miropoler tsadik possesses his own lyrical qualities, an especially tremulous tenderness and a touching mixture of spiritual helplessness and courage.

Goldenberg’s Azrielke is much shorter in stature than Samuel Goldenberg. Stooped over from decades of study, infused with the pride and spiritual power that derive from philosophical discernment of his own insignificance, his tsadik breathes with the refined air of tragedy. That is precisely how it had to be with the living symbol, the genuine tsadik in whom there flickered the spirit of his great forebears. He is the last in a powerful spiritual lineage, tormented with doubts, within whom the fires of self-belief flare up only sporadically.

That is how Goldenberg played him, without a shadow of artifice—consistent, sincere.

It was interesting to see Elye Tenenholtz in the role of the Messenger [meshulekh]: in the first act, just a superficial albeit very imposing figure, and a strong if somewhat immobile [farglivert] mask. But in the second act, when he speaks to Leah (the bride), his face—his mask—takes on life through the heart-rending menace of his trembling voice, especially in the moment when he announces the advent of the dybbuk.

Finale of Act 1 of The Dybbuk, in the 1922 production by Habima in Moscow. Lower right: Khonen (played by Miriam Elias) lies dead from a fit of kabbalistic self-mortification. Source: Vakhtangov Theatre Museum; reproduced in Andrei Malaev-Babel, Yevgeny Vakhtangov: A Critical Portrait (London; New York: Routledge, 2013).

The play is performed here according to Dovid Herman’s “edit.” The Messenger (and not the rabbi) speaks on behalf of the deceased, and Tenenholtz’s scene by the synagogue’s partition [mekhitse] is one of the most impressive scenes in the production. The Messenger’s mysterious qualities are revealed here, as with the Vilna Troupe, through his intercession between the dead and the living in the religious, spiritualistic séance. Like a trembling wave that has crashed over the deck and inundated everything around it, his singsong words emanate from “the world beyond,” and Tenenholtz performed the bulk of this dominating scene with sensitivity. Only occasionally did it seem evident that the actor was “jumping into” the role because he had not fully managed to memorize the text, which harmed his intonation every now and then. But overall, Tenenholtz’s performance persuades one that he was absolutely cut out for a role like the Messenger.

The role of Khonen was played here by a woman, Miss Chana Spector, who in fact is just a beginner—and she was astoundingly good in the role, even if she was not altogether able to conceal her feminine figure.

Morris Dorf, in the role of Sender Brinnitzer, performed with fine sensitivity and tact, and showed that we are seeing the growth of a good character actor.

Madame Annie Augenblick’s performance of the scene in the synagogue was heartfelt (in the role of the Jewish woman who falls before the holy ark [aron ha-kodesh] beseeching a remedy for her sick daughter) and she left an impression.

Ella Zibel, in the role of a woman who symbolizes death, is an impressive character. She resembles somewhat the figure in the Vilna Troupe who does the dance of death but is more realistic and down to earth. She comes to the paupers’ meal at the wedding while the bride briefly remains by the grave, and she dances alone, facing the bride while humming a strangely piercing tune.

Yiskah Frenkel modestly and pleasingly played the role of Leah’s friend Gitl. In the second act she was very lively while “leading” the cluster of girls who come running, while gossiping about the groom’s appearance.

Moishe Silberstein, in the role of the sexton [shamès], would have been able to play a fine and touching shamès had he taken the effort to consider his role a little, learn his lines, and drive away the buffoon comedian that always lurks over his shoulder.

Irving Jacobson played the groom’s teacher [melamed] with vivacity – but please, may we be spared such vivacity, a vivacity of exaggerated gesticulations and comical pranks that are calculated to provoke a cheap laugh. Our Irving Jacobson is a capable young actor and for this very reason he deserves to be rapped across the knuckles for such a burlesque of a melamed in a play like The Dybbuk.

Show respect, ye comedians, to a work of the spirit!

In contrast, yet another compliment is due the actress Annie Shapiro for her performance as Fradye (Leah’s grandmother). To play that role after Bina Abramowitz performed the same role at the Art Theatre with so much charm, and to make such a good impression as Madame Shapiro made – that is quite an achievement for an actress.

Of the synagogue idlers [batlonim], the third one (Samuel Kohn) was more interesting than all of the others, both in appearance and in manner of speaking. N. Fabol (the second batlen) performed with intelligence and vivacity, but without much characterization—and Sigmund Zuckerberg’s first batlen was performed without any characterization whatsoever. Mr. Gross was quite pallid in the role of Henekh.

My intention was to write only a short notice about The Dybbuk at the Amphion Theatre, but as I began to recall the details of the performance, I felt that it would be most unfair not to spend time on the entire piece in some detail. Such honest acting on the part of most of the performers and so sincere an attitude—these are rare not only in a “neighborhood theatre,” but even in a large commercial theatre in New York.

It’s only regrettable that the businessmen of that theatre were scared to “take a chance” and keep the play running for a few more weeks. Based both on the “Dybbuk Week” and the other “literary” productions of theirs [at the Amphion], it could, and it should have occurred to them that they would have taken a very small risk, as compared with any cheap shund play whatsoever, please excuse the comparison.

Introduction and translation by Zachary M. Baker.

Notes

-

1Concerning the Vilna Troupe’s production of The Dybbuk, see, Debra Caplan, Yiddish Empire: The Vilna Troupe, Jewish Theater, and the Art of Itinerancy (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018); Michael Steinlauf, “‘Fardibekt!’ An-sky’s Polish Legacy,” in The Worlds of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Intellectual at the Turn of the Century, eds., Gabriella Safran and Steven J. Zipperstein (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 232–51. A key point of Caplan’s study is that the Vilna Troupe fragmented into several ensembles that claimed that name.

-

2In the Yiddish Art Theatre’s September 1924 revival of The Dybbuk, Lazar Freed, as Khonen, played opposite Leah Rosen (whom Schwartz had recently “imported” from Germany) in the role of Leah.

-

3For example, although the Forverts ran brief announcements and small-print ads for the Amphion’s Dybbuk production, that newspaper did not review it.

-

4Abraham Cahan, “Di viener shoyshpielerin Leye Rozen in Shvarts’es kunst theater,” Forverts (New York), September 9, 1924.

-

5On Vakhtangov’s production of The Dybbuk with Habima in Moscow, see, Nick Worrall, Modernism to Realism on the Soviet Stage: Tairov-Vakhtangov-Okhlopkov (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 120–37; Vladislav Ivanov, “An-sky, Evgeny Vakhtangov, and The Dybbuk,” in The Worlds of S. An-sky, 252–65; Malaev-Babel, Yevgeny Vakhtangov, [195]–214. In 1926-1927, when the Habima troupe visited New York and put on The Dybbuk, Celia Adler came away positively awed by Hanna Rovina’s performance as Leah. (A male actor, Ari L. Warshawer, was that production’s Khonen.) See Celia Adler, with Yankev Tikman, Tsili Adler dertseylt (The Celia Adler Story) (New York: Celia Adler Foundation, 1959), 561.

-

6Chayele Grober, Tsu der groyser velt (Hacia un gran mundo) (Buenos Aires: “Byalistoker vegn” baym Byalistoker farband in Argentine, 1952), 122.

-

7Andrei Malaev-Babel, Yevgeny Vakhtangov: A Critical Portrait (London: Routledge, 2013), 210.

-

8Ruthie Abeliovich, Possessed Voices: Aural Remains from Modernist Hebrew Theater (Albany: SUNY Press, 2019), 75.

-

9Naomi Seidman, “The Ghost of Queer Loves Past: Ansky’s ‘Dybbuk’ and the Sexual Transformation of Ashkenaz,” in Queer Theory and the Jewish Question, eds., Daniel Boyarin, Daniel Itzkovitz, and Ann Pellegrini (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 233, 237.

-

10Malaev-Babel, Yevgeny Vakhtangov, 213.

-

11R. Ben-Ari, Habimah (Chicago: L. M. Stein, 1937), 221.

-

12Nick Worrall, Modernism to Realism on the Soviet Stage, 124.

-

13For an account of Miriam Elias’s years in America, see “Aunt Miriam, Diva,” by her grand-niece Dana Susan Lehrman, Retrospect website, February 22, 2020, https://www.myretrospect.com/stories/aunt-miriam-diva/.

-

14Adler wrote about the Yiddish Art Theatre’s 1921 production of The Dybbuk in her memoirs, and listed several members of the Kunst-ring group who participated in it. See Tsili Adler dertseylt, 555–74.

-

15In 1921, at the Yiddish Art Theatre, Zvee Scooler played the unfortunate groom whom Leah’s father had chosen instead of Khonen.

-

16Tsili Adler dertseylt, p. 568. Spector’s first name was usually spelled Channah in English.

-

17Tsili Adler dertseylt, pp. 573, 605.

-

18In 1926, four years after Vakhtangov’s death, the Habima troupe departed Soviet Russia and embarked on a series of international tours, with many of its members eventually ending up in British Mandate Palestine where they reconstituted the company.