Caricature of Maurice Schwartz, from his 1930 visit to Argentina. Artist: M. Kantor. Source: Di idishe tsaytung – Diario israelita (Buenos Aires), June 29, 1930.

Ven Moysh iz geforn: Maurice Schwartz on the Yiddish Theatre in Argentina in 1930 (Part I)

Zachary Baker

The Yiddish theatre occupied an important position in the transnational cultural system of Yiddishland. 1 Yiddish actors and troupes wandered from city to city and across boundaries and oceans. The major stars brought along scripts of original and translated plays, stage instructions, costumes, sets, and sometimes even stage equipment. 2 Argentina was a node in an international network comprising locally based theatre owners, impresarios, actors, musicians, and crews, plus the guest stars and directors from abroad. At the same time, the Argentine Yiddish theatre functioned within the diverse and multilingual theatrical ecosystem of Buenos Aires. 3

In the second half of May 1930, Maurice Schwartz (1889-1960)—Yiddish actor, director, impresario—embarked upon a seventeen-day sea voyage that took him from New York to Buenos Aires, Argentina. This was his first trip to South America and also the first time that he traveled abroad as an individual guest star on the international Yiddish theatre circuit. 4 Schwartz was accompanied by his wife Anna; when they reached Argentina, they met up with Joseph Schwartzberg, a New York actor who served as advance man and stage manager for Schwartz’s tour.

Having led New York’s Yiddish Art Theatre since its founding in 1918, Schwartz enjoyed a worldwide reputation as one of the leading exponents of the “better” theatrical repertory. At no point during its more than thirty years of existence was the Yiddish Art Theatre ever on secure financial grounding—not even after the company had built its own theatre on Second Avenue in the mid-1920s. Following the Wall Street crash of October 1929, it was in notably dire straits, so the invitation to perform in Argentina thus came at an opportune time for Schwartz, since it would enable him to pay off some of his company’s debts. As the Buenos Aires-based actor-impresario Leon Brest put it, “The chief purpose of your tour is to make money—and that will be an absolute, 100 percent certainty.” 5 During the course of his ten-week stay in Buenos Aires, Schwartz mounted over a dozen plays at two centrally located theatres, the Teatro Nuevo and the Teatro Argentino, following which he took his act to several Jewish communities in the Argentine provinces (including the agricultural colony Moisés Ville), and then, as he wended his way home, Montevideo, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro. Though many of the plays that Schwartz staged in Buenos Aires had been produced there before, by other actors—some of them multiple times—critics greeted his tour as a “sensation.” 6 Subsequently, Schwartz would frequently return to South America, up until his death in 1960.

Along with his stage performances, the South American tour offered Schwartz another way to augment his income. The New York Yiddish daily Forverts commissioned him to write a series of ten travelogues, which were published in that newspaper between June 28 and October 11, 1930. And after he had spent a few weeks in Buenos Aires, his journalistic horizons expanded to include both of that city’s Yiddish dailies, Di prese and Di idishe tsaytung, and the weekly magazine Der shpigl. 7 His articles were conversational in tone and punctuated with amusing anecdotes. Schwartz’s observations were informed by his extensive involvement with the Yiddish theatres of New York City during his nearly three decades of life in the United States, since his arrival there in 1901 at the age of twelve.

“All the World’s a Stage”

The travelogues were calculated to convey Schwartz’s sense of wonder at the sights and sounds of South America, while also holding up a mirror to his readers—Yiddish-speaking immigrants living under rather different conditions in New York and other large North American cities. Most of them would have experienced an ocean voyage when they emigrated from Europe to the Americas. However, their trips were one-way, from east to west, across the Atlantic, usually in the cramped quarters of steerage. By contrast, Maurice and Anna Schwartz were joined in first class on the SS Southern Cross by just forty-eight other passengers. The liner made several calls along the way, to pick up and drop off cargo and passengers. 8

Schwartz populated his South American travelogue with theatrical allusions. Take, for example, his depiction of the scene aboard the boat at the New York pier just before its departure. Hollywood movies of the era convey some of the excitement surrounding a ship’s departure from its home port. Friends and relatives mingled with passengers during the frenzied moments before the ship’s whistle signaled non-passengers to come ashore. Schwartz captured the festive mood of this moment by likening it to “the most powerful and theatrical crowd scenes,” such as those in the German director Max Reinhardt’s production of Romain Rolland’s play Danton. As the ship passed from the “familiar [heymisher] sea” to the open ocean and the lights of Coney Island receded into the distance, Schwartz thought about the many times that he bathed there and recited lines together with his fellow actors in nearby Seagate. 9

Brazil and Uruguay

Schwartz depicted the breathtaking approach to Rio de Janeiro at sunrise as “the gate of Paradise,” likening the clouds to “the production of a heavenly spectacle, and the performers are the amazing colors [that] change so quickly.” The mountains surrounding the city’s harbor, among them the famous Pão de Açúcar (Sugar Loaf), augmented the theatrical impression of arrival in the Brazilian capital. Schwartz was encouraged by his encounters with local Yiddish journalists and by the committee of young men and women “with pioneering spirit” who came to meet him at the pier, and he promised to give a few performances in Brazil on his return voyage. 10

From there, the ship proceeded to Montevideo, the penultimate port of call, where Argentine Yiddish impresarios often met their guest artists and escorted them to Buenos Aires. Schwartz was greeted at the pier by the editors of a local Yiddish newspaper and magazine, and also by a few actors visiting from Buenos Aires who hoped to set up a permanent Yiddish theatre troupe in the Uruguayan capital. Schwartz expressed the hope that he, too, would perform there on his return trip to New York. Overall, Uruguay’s talent pool was not sufficient to sustain full-time theatre companies, Schwartz was informed. Instead, companies visited from abroad to perform “the best dramas, operas, and operettas” in Spanish, German, and Italian.

Schwartz passed by the government’s main office building, at the Plaza de la Independencia, commenting that it was a little smaller than Cooper Union (i.e., not particularly large) and guarded by three armed soldiers who reminded him of theatrical extras. The soldiers yawned as they impatiently anticipated lunchtime. Indeed, the entire city practically shut down during the two-hour lunch break. A restaurant in Montevideo was a “factory,” Schwartz wrote, where the “labor” consisted of consuming liquor, appetizer (“sufficient for the Erev Yom Kippur meal”), soup, meats accompanied by wine and beer, and Brazilian coffee, in that order. 11

Arrival in Buenos Aires: Impressions of the City

Schwartz’s accounts of his brief visits to Rio and Montevideo were but a prelude to the main event, Argentina, where he would remain for three months. In Buenos Aires, he was ferried around town, wined and dined, and feted by cultural organizations. His comings and goings were accorded blanket coverage by the Yiddish press, and he catered to this outpouring by graciously making himself readily available for interviews and generously consenting to publicize his presence further through the articles that he contributed to local journalistic outlets. Schwartz’s theatrical productions were reviewed by the two Yiddish newspapers and a few of them also by Spanish- and German-language newspapers in the Argentine capital.

From the moment that he stepped off the boat he was dazzled by the sounds, gesticulations, speech, restaurants, cafés, and clothing of this “world metropolis”—the “Paris of America.” Schwartz shared his impressions of the Argentine voice: The Argentine “r” is strongly trilled; the name of one popular newspaper (“a cousin to our New York American,” a Hearst paper) was pronounced “La crrrrítica” by locals. He was captivated by the singing newsboys, chanting newspaper headlines and the plot summaries of pulp novels: “[Joseph] Rumshinsky could definitely compose an interesting song number for Molly Picon from them.” The newsboys all sang the same tune, “just as all Jews sing a single Kol Nidre melody.” The city’s many newspapers, he noted, blared headlines and featured large photos like the New York Daily News. Some printed four to six editions each day, “just as in New York.” In these papers “they read about football, horse races, prize fights, [and] theatre.”

Jewish immigrants quickly picked up the ubiquitous expression “sí-sí.” When Schwartz’s “still green” uncle met him at the ship, “he kisses me and weeps and shouts [in Yiddish], ‘My Moyshele, sí-sí, I’ve missed you for so long, sí-sí! How’s your father? sí-sí! What’s doing in North America? You make a better living there, sí-sí!” This verbal tic even infiltrated the speech of Yiddish actors at rehearsals:

I’m going over a scene in [Sholem Aleichem’s] Tevye with an actress. As she recites [the prayer] “Got fun Avrom” I ask her to convey the words with greater emotion, so that it doesn’t sound like she’s shouting. The actress stands still, looks [at me], her eyes filled with tears, and responds, “Sí-sí, Señor Schwartz; you’re right! Sí-sí, it’ll be boyne [i.e., bueno].”

There were more theatres in Buenos Aires, per capita, than in New York City, Schwartz reported. “They go to the theatre because they need the theatre, because the theatre is a part of their life’s routine.” One element of culture shock was that evening performances began as late as 10:00 p.m., and often wound up after 1:00 in the morning. 12 Then, following the evening’s entertainment, “going to a café is practically a law here, and you snack on a couple of meaty sandwiches with café negro.” Street life in Buenos Aires was cheerful, like “before a wedding.” With the hours that they kept, people in Buenos Aires didn’t get much sleep: “Can you possibly sleep, then, when you’re getting ready for a wedding?”

Movies were just as popular as the theatre, if not more so, and tickets were almost as expensive. At the time of Schwartz’s visit, Maurice Chevalier’s movie “My Love Parade” (1929; directed by Ernst Lubitsch) had been playing for four months to full houses. Dozens of cinemas showed talkies that were produced in Hollywood and screened in Buenos Aires without dubbing or subtitles – instead, they were accompanied by program booklets in Spanish. Among the prominent locals whom he met was Max Glücksmann, “the William Fox of South America” and a devoted Jewish philanthropist. “He is a very original and strong personality.”

The narrowness of the streets and sidewalks of central Buenos Aires caused pedestrians to bump against one another, reminding Schwartz of scenes in the Abraham Goldfaden play Di kishef-makherin (The Sorceress). 13 The majority of houses – and also “many hospitals, restaurants, and theatres lack ‘steam’ [central heating] and must make do with electrical and oil [space] heaters,” Schwartz observed, an observation that became a leitmotif of his travelogue. 14

In the course of his first three weeks in Buenos Aires, Schwartz calculated that he had consumed more liqueurs than during the three previous decades. Everyone drank there, if only to stay warm; otherwise, the chill crept into the bones. Each day, the actors rehearsed in their winter coats, their teeth chattering, and they warmed themselves up with spirits. “The poor actors need a little ‘steam’!… Steam is a theatrical attraction. You read a newspaper advertisement: ‘Attention! Our theatre is heated with calefacción (steam).’” But calefacción alone was not enough; during intermissions theatre concessionaires offered hot coffee, Ocho Hermanos (a liqueur), and Benedictine. 15

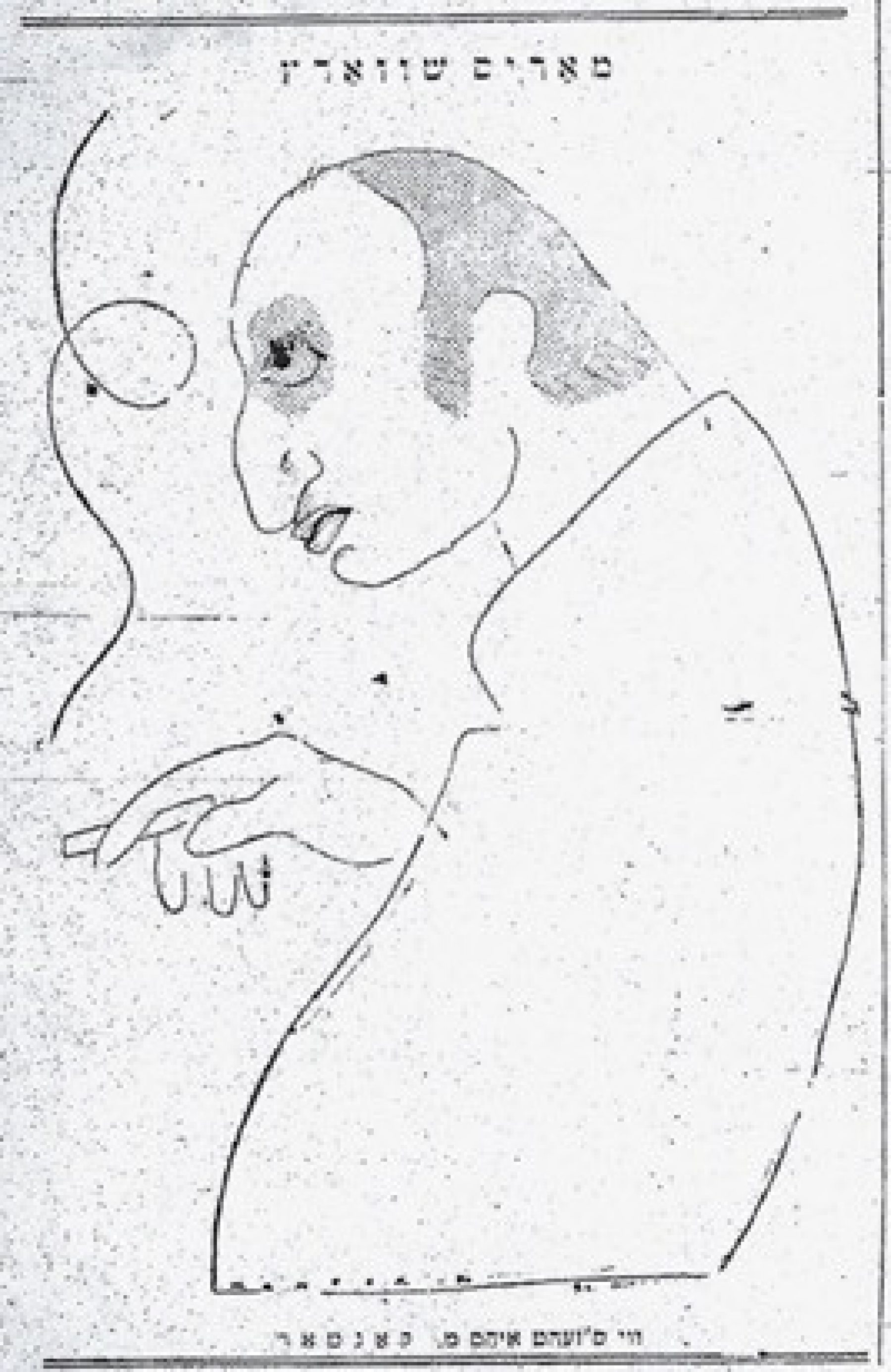

The seating plan of the Teatro Argentino. Source: Penemer un penem’lakh / Caras y caritas, no. 227 (Buenos Aires), January 11, 1929.

The Theatre Scene in Buenos Aires

In his travelogue, Schwartz naturally devoted a considerable amount of attention to theatre in general and the Yiddish theatre in particular: actors, repertory, productions, audiences, and finances. The comparisons between North and South American practices began at the box office and continued through the hall onto the stage and, from there, into the wings.

Publicity. Upon arriving in Buenos Aires, Schwartz noticed the lithographed posters announcing his forthcoming performances. The posters showed him in full, bewigged, eighteenth-century regalia as Joseph Süss Oppenheimer in the play Jud Süß (based on Lion Feuchtwanger’s novel about the eighteenth-century Court Jew), which he had first staged in New York the preceding October and put on in Buenos Aires in mid-June 1930. 16 Later, when he asked the impresario Adolf Mide why the posters remained up after he had moved on to other plays, he was told that his costume and makeup lent him a commanding appearance. “Jews have respect for generals, ministers, and presidents”; thus, the actor acquired the temporary nickname of “General Schwartz.” 17

The box office. The box office cashiers hoarded the best tickets, he commented, and to get a good seat in the orchestra (platea, in Spanish) or the boxes (palcos) theatregoers needed to tip the cashiers. Close and reciprocal relationships prevailed between audience members and the cashiers, “but friendship is friendship and tips are tips.” At one of the theatres where Schwartz was performing, “the cashiers have grown gray while taking tips. Their grandchildren often visit their grandfathers at the box office.” And from there, the grandfathers were “transferred to their final resting place[s].” (The cashiers would have been Spanish-speaking Argentines, as the theatres were owned by Christians and rented out on a seasonal basis to the Yiddish impresarios. 18 ) This depiction of box-office operations in Buenos Aires would have struck New York newspaper readers as odd because, by contrast, that city’s Yiddish theatres were heavily unionized at all levels. Ticket sales for Schwartz’s productions were brisk; he compared the scenes around the box offices to the pandemonium on the trading floor at the Stock Exchange.

The audience. Buenos Aires Yiddish audiences were easily “ignited”; a few of Schwartz’s productions, such as Got fun nekome (God of Vengeance), by Sholem Asch, and Bloody Laughter (Hinkemann), by Ernst Toller, elicited some of the strongest applause that he had ever received. A powerful and climactic end to an act catalyzed this level of enthusiasm. Such hyper-enthusiasm was a mixed blessing, he felt. It evoked the theatrical climate of New York during the Jacob Gordin era, when Kenny Liptzin and Jacob P. Adler were the top stars.

Schwartz claimed that Buenos Aires audiences were befuddled by practices that he had instated at the Yiddish Art Theatre and followed in Argentina, such as raising the curtain and taking bows only at the conclusion of the final act (rather than at the end of each act), and not singing encores of songs. “Ensemble performance… is unknown here,” he wrote. “People come to see the star” (of which he was one). And for that reason, Schwartz encountered complaints when he played secondary roles – rather than starring – in The Blacksmith’s Daughters, by Peretz Hirschbein, and Kidush-hashem, by Sholem Asch. “The audience didn’t know what to do when an act ended with a different actor, and not with me.” He explained this as follows: “The Yiddish audience here is inclined more toward melodrama or operetta, because that is what it’s been fed, year-in and year-out.” (“And is it any better in New York?” Schwartz was asked.)

Also, the Buenos Aires audiences didn’t laugh as loudly or heartily at the comedies by Sholem Aleichem and Peretz Hirschbein, as in other cities where he had put them on, including London, Paris, and Vienna. Comedy wasn’t often performed here, he claimed by way of explanation. 19 Rather, “the audience is accustomed to the silly joke in an operetta or melodrama.” On balance, though, Schwartz considered his performances to have met with an extremely appreciative reception. “Here, in Buenos Aires, the audience hungers after theatre. They run to the theatre and love theatre.”

The auditorium. Schwartz’s performances took place in two different theatres in the center of the Buenos Aires theatre district: Teatro Argentino and Teatro Nuevo. The impresario Adolf Mide had been able to negotiate only very short-term leases with the theatres, necessitating an abrupt change in venue in the middle of the ten-week tour. Schwartz commented at length on the layouts of the theatre auditoriums, homing in on the number, size, and function of the boxes—palcos in Spanish and palkes in Argentine Yiddish. Each theatre had from forty to eighty of them, in that respect resembling the old Metropolitan Opera House (which was demolished in the 1960s), he wrote. The city’s newspapers, Spanish- and foreign-language alike, were allocated a palco, regardless of who owned or was renting the theatre. The newspapers’ critics offered their palcos to guests and friends as well. If they didn’t show up for a performance, their palcos remained unoccupied.

At benefit performances, organizations renting the theatres needed to request permission from the “owners” of the palcos, to occupy their boxes. 20 Ordinary audience members also rented palcos and packed in as many friends as they could fit, at a cost of one peso, or about thirty-five US cents per person. Many women who rented palcos brought along their children “and even infants” because it was cold inside at home – and warm at the theatre. It was even warmer in the boxes than in the orchestra seats, because people were tightly packed and they “create[d] their own calefacción,” Schwartz remarked.

Distractions in the house. There were some negative aspects to performing in Buenos Aires, however. “In the strongest dramatic scenes, crying can suddenly burst out in the theatre,” Schwartz remarked. Sometimes this bawling reverberated between “dueling” palcos. During one performance of Bloody Laughter, Schwartz had to lower the curtain and “wait until the children had cried themselves out.” Such distractions were “not unique to the Yiddish theatre, but [take place] in the Spanish theatre and also at [Aleksandr] Tairov’s Russian performances, [where] the children help to create a ‘theatrical’ mood.”

Nor were the aural distractions limited to the youngest members of the audience. The stagehands, actors, extras, and musicians all “talk and talk,” Schwartz reported, “and they don’t permit the show to go on.” People in Buenos Aires had a natural tendency speak especially loudly in public places such as restaurants, but it became insufferable during key moments of plays like Tevye and Shabetai Zvi, when it was impossible to stop the action on stage—because if you did, you’d hear the stagehands chattering about their lottery tickets or about football. Schwartz didn’t find the daylong rehearsals to be wearying; however, “my nerves simply become frayed by the noise that is emitted by the children in the theatre—and the big children on stage.” The Argentine government ought to decree that they wear locks around their mouths during performances, he grumbled. 21

The stars and the actors. “American stars are the cat’s meow here,” Schwartz wrote. “I was proclaimed the ‘Conqueror of the World,’ ‘the Genius of the Twentieth Century,’ the ‘Most Famous,’ the ‘Greatest.’ Napoleon is a blade of straw in comparison.” But this level of hyperbole was precisely what the local audience had come to expect. “It must swallow everything that is sold.” Each theatre season, half a dozen or so guest stars from overseas visited Argentina. The most popular attractions of the previous (1929) season were the comedian Menashe Skulnik and the operetta star Nellie Casman. “Everyone talks about Menashe Skulnik,” Schwartz remarked. “Skulnik is a dream, a legend here. And Nellie Casman! The walls, the houses, the streets weep and long for her. In the hospitals and orphanages, at every celebration, you hear one big song, ‘Yosl, Yosl’!” 22 This led Schwartz to ruminate on the situation in New York, where actors were valued according to the wages that they received ($600 to $700 a week, for the stars)—and managers for the profits that they generated.

The Yiddish actors of Buenos Aires were hard workers, Schwartz wrote, but they struggled with Sholem Aleichem’s rich language because they had become inured to the flat prose of the shund plays. In the absence of Jewish drama schools the local Yiddish actors lacked formal training. 23 Thus, Schwartz encountered a situation where “everyone was on his own, with all sorts of dialects—Lithuanian, Polish, Romanian, Belorussian—a mix of gay (go; Polish Yiddish pronunciation) and shtay (stand, remain; Polish Yiddish pronunciation), tote (father; northwestern Ukrainian Yiddish pronunciation), mome (mother; northwestern Ukrainian Yiddish pronunciation), shvyester (sister; Russian-inflected Yiddish), futyer (fur; Russian-inflected Yiddish), etc.” Schwartz toiled for long hours to iron out the actors’ accents and improve their stage technique. “I led rehearsals with them for twelve to fourteen hours a day. Their eagerness to learn did not tire me out.” And “lo and behold, it was discovered that some of them have talent; with their new voices they’ve begun to speak. They don’t shout or babble or wave their hands around” anymore.

The Yiddish repertory. Schwartz complained that scripts for plays then being produced in New York were incorporating a “mutilated English” in the vain hope of retaining younger audiences. (Quite often, the plays that other guest stars produced in Argentina included words, phrases, and even dialogue in English, a language that was largely unintelligible to local audiences.) He conceded that operettas and melodramas were welcome, so long as they were tastefully written and produced, as with plays on Broadway (though not so much on Second Avenue). “It’s like a good wine: It makes you happy but doesn’t get you drunk.” But the theatre needed to be respected and loved as an art form.

The plays that Schwartz put on in Buenos Aires were staples of the Yiddish Art Theatre’s repertory: literary works by classic and modern Yiddish and European authors. “I wanted to mount complete productions,” he wrote. But, at the rate of one play (or even more) each week, each production was granted only eight rehearsals (two per day), so he recognized that his ambitions were unrealistic. Nevertheless, Schwartz felt that the local actors gained a lot through his guidance; they “speak Yiddish for hours on end and are serious about applying their makeup for even the smallest roles.”

What will happen after I leave? Schwartz wondered. Will the actors revert to their old habits? His advice: “The critics and actors ought to convene a conference and secure the existence of a better Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires.” The local Yiddish press needed to encourage such a development by publishing Yiddish literature and world literature in translation—and the global Yiddish theatre should follow suit and unite against the “Menakhem Mendl impresarios” who were ruining the Yiddish theatre. Conditions in Argentina were favorable to such a development. “The immigration wave… will continue and Buenos Aires will in the future become a second United States,” he predicted. Sadly, his next prediction would turn out to be even less accurate: “The current [economic] crisis is just a light breeze that will blow over.” 24

Paper decorations and fire hazards. During the 1930s, several of the North American guest stars commented on the deployment, in Argentina’s theatres, of paper decorations as backdrops and screens depicting palaces, forests, seas, stables, and other stage scenery. Schwartz was fascinated by this practice, which he attributed to the theatrical traditions of Spain and Italy. Canvas backdrops and sets constructed from wood were unheard of in Buenos Aires, he contended. The head set designer at an opera house (probably the Teatro Colón) showed him forty-year-old paper decorations that the theatre used and reused for several productions (he mentioned Aida, Carmen, and Otello), which looked as good as new. Troupes touring the Argentine provinces brought along crates containing paper decorations for twenty to thirty different plays, which were unfurled on stage, fresh and unwrinkled.

The colors were more vivid on these paper decorations than on canvas, Schwartz noted, and a stage production in Argentina cost “exactly ninety percent less” than in the US. “The two productions of Shabetai Zvi and Kidush-hashem together didn’t cost as much as a week’s salary for one of our stagehands” at the Yiddish Art Theatre. Set designers were paid a monthly fee by the impresarios. In a flourish of hyperbole, Schwartz remarked that with these kinds of savings, the Yiddish Art Theatre could have bought up several theatres in Buenos Aires. 25 (Of course, the powerful theatre unions of New York would never have tolerated such an arrangement back home.)

Accidents sometimes happened on stage, Schwartz wrote, when absent-minded or nervous actors sometimes poked through the paper screens. This occurred during one performance of Tevye, when the dairyman’s grandchildren burst through a wall. However, the Buenos Aires public was accustomed to such incidents.

Reliance on paper sets was obviously a fire hazard, so the city of Buenos Aires enforced strict fire regulations inside the theatres. Hoses were suspended over the stages and there was an iron screen (ostensibly fireproof) at the front of the stage. Candles and “Bengal fire” 26 were permitted on stage, notwithstanding the paper decorations. Fire-fighters were stationed in the theatre at each performance—and during the show they too chatted audibly with the manager and the ushers. Two fire-fighters were stationed by the entrance to the stage and kept watch through small windows. They occasionally stuck their heads through the windows and could be seen by the actors and the audience. The fire-fighters “smile when the audience laughs—and often wipe their eyes.” This actually happened during a scene of Asch’s play Kidush-hashem. 27

Part II is here.

Notes

-

1A fairly extensive literature has arisen concerning the concept and concrete manifestations of Yiddishland. A good starting point is Jeffrey Shandler’s book Adventures in Yiddishland: Postvernacular Language & Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006). Debra Caplan’s book Yiddish Empire: The Vilna Troupe, Jewish Theater, and the Art of Itinerancy (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018) provides a case study of the ways in which transnationalism was baked into the Yiddish theatrical endeavor.

-

2For example, in 1930 the Argentine Yiddish actor-impresario Leon Brest advised Maurice Schwartz to bring along his costumes and a few “spots” (spotlights). Brest to Schwartz, March 18, 1930, folder 55, box 6, Maurice Schwartz Papers RG 498, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Archives, New York (henceforth YIVO). In 1939, Herman Yablokoff brought along “large crates with costumes for my productions, microphones, amplifiers, a record player, crates with projectors, reflectors, dimmer-boards, ‘gelatin’ (colored reflector paper), special curtains, and painted canvas decorations. I had been informed that these things were not available in Buenos Aires.” See Herman Yablokoff, Arum der velt mit idish teater (Around the World with Yiddish Theatre), vol. 2 (New York: 1962), 368, 386–387, 399–400.

-

3For an overview of the theater in Argentina from its beginnings to 1956, see Beatriz Seibel, Historia del teatro argentino (Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 2002-2010; 2 vols.). Its chronological, annotated arrangement covers “national” (Argentine) companies, troupes specializing in peninsular Spanish repertory (e.g., zarzuela), French- and Italian-language companies, variety and cabaret troupes, and even circuses. The Yiddish theater and its connections to the “national” theatre of Argentina are also mentioned.

-

4In the mid-1920s, Schwartz toured Western Europe together with his company, the Yiddish Art Theatre.

-

5Brest to Schwartz, March 18, 1930, folder 55, box 6, Maurice Schwartz Papers RG 498, YIVO.

-

6Samuel Rollansky (Shmuel Rozhanski), “Der idisher teater inm yohr 1930,” Di idishe tsaytung (Buenos Aires), January 1, 1931.

-

7Three of his Forverts travelogues were picked up by Di prese and in Der shpigl he published a couple of travel pieces to supplement those that were appearing in the New York paper. In addition, Schwartz wrote articles on other theater-related topics for these publications.

-

8A fair number of middle-class North American Jews would re-cross the Atlantic during the interwar decades, both on business and to visit relatives in Europe. “Going Home” is the theme of volume 21 of the YIVO Annual, edited by Jack Kugelmass (Evanston: Northwestern University Press; New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 1993).

-

9Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts bashraybt zayn rayze keyn Argentine,” Forverts, June 28, 1930.

-

10Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts bashraybt di vunder-shehne shtodt Rio de zhaneyro fun Brazil,” Forverts, July 5, 1930.

-

11Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts bashraybt di kleyne zid-amerikanishe land Urugvay,” Forverts, July 12, 1930.

-

12According to Herman Yablokoff, evening performances in Buenos Aires ran from 10:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. (versus 8:30 to 11:30, in New York); and matinées (vermut) from 6:00 to 9:00 p.m. (versus 2:30 to 5:30, in New York). This meant that on weekends, when there were two performances each day, actors had only an hour of down time between 6:00 p.m. and 1:00 a.m. See Herman Yablokoff, Arum der velt mit idish teater, vol. 2, 392.

-

13Maurice Schwartz, “Oyf di gasen un in di teaters fun Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, August 28, 1930.

-

14Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts shildert Buenos Ayres, di ‘Pariz’ fun Amerike,” Forverts, July 19, 1930.

-

15Maurice Schwartz, “Stsenes un bilder fun idishen leben in Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, August 2, 1930.

-

16Samuel Goldenberg, who had co-starred with Schwartz in the New York production of Jud Süss, put on the same play in Buenos Aires about a week later. At the Yiddish Art Theatre, the two actors switched off the two leading roles, Süss and the Duke of Württemberg.

-

17Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts shildert stsenes un bilder in di shtetlach fun Argentine,” Forverts, September 27, 1930.

-

18In New York, many of the Yiddish theaters were owned and operated by fellow Jews. According to the Yiddish actor Herman Yablokoff, the cashiers in Buenos Aires were tipped in lieu of receiving salaries. See Herman Yablokoff, Arum der velt mit idish teater, vol. 2 (New York: 1962), 389–391.

-

19Here, Schwartz was ignoring his own comments regarding the enthusiastic reception that the comic actor par excellence, Menashe Skulnik, had received during the previous two seasons in Buenos Aires.

-

20Theater benefits were special events that were held to honor a guest actor, a member of the troupe, or a charitable cause, with proceeds flowing to that individual or institution.

-

21When the young primadonna Miriam Kressyn visited Buenos Aires in 1931, she published an article in the weekly magazine Der shpigl, in which she implored theatergoers to show up at the theater punctually, maintain better decorum, and—especially—keep their small children under control. See “Meynungen vegn hign teater bazukher,” Der shpigl, September 11, 1931. Herman Yablokoff noted that his theatre’s crews were Spanish-speaking Argentines (except for the electrician, who spoke only Portuguese). See Herman Yablokoff, Arum der velt mit idish teater, vol. 2 (New York: 1962), 387.

-

22Casman met with a wild reception on the part of audiences—and nearly unanimous condemnation by the critics, who considered her risqué songs and performances to be pornographic.

-

23In 1930, many of the better trained, veteran Yiddish actors in Buenos Aires performed at the Teatro Excelsior, including Sarah Sylvia, Zina Rapel, Samuel Iris, and Leo Halpern. The Excelsior’s orchestra was led by the noted Argentine composer Jacobo Ficher, and the company was directed for over half of its eight-month season by Samuel Goldenberg. All of this was ignored by Schwartz.

-

24Maurice Schwartz, “Moris Shvarts vegen idishen teater in Nyu York un in Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, August 21, 1930.

-

25The director and writer Jacob Mestel, who visited Buenos Aires together with Jacob Ben-Ami in 1931, took a more jaundiced view of the paper sets and predicted that, “with the rise of the modern theater in Argentina…the paper decorations will have to disappear.” See “A shmues mit beyde Yankevs,” Der shpigl, September 18, 1931. Herman Yablokoff also discussed the paper decorations in his memoir, Arum der velt mit idish teater, vol. 2 (New York: 1962), 387–388: “It’s utterly impossible to recognize that the rooms; palaces; landscapes showing sky, water, mountains, valleys, fields, and forests; [and] streets and houses are actually made of paper. The paper decorations on stage create the illusion of massiveness and reality. The paper decorations do have one defect: as the saying goes, ‘Look, but don’t touch!’”

-

26Bengal fire is defined as “flare candles…used to achieve indirect pyrotechnic lighting of surfaces or buildings.” See “Bengal fire,” PyroData: Pyrotechnics Data for Your Hobby (https://pyrodata.com/definitions/Bengal-fire).

-

27Maurice Schwartz, “Oyf di gasen un in di teaters fun Buenos Ayres,” Forverts, August 28, 1930.