“Bono Ladrillo” (Brick bonus) for the construction of an IFT playhouse. Source: Archivo Teatro IFT, Centro Documental y Biblioteca "Pinie Katz" (CeDoB "Pinie Katz").

Between Biznes and Art: Commercial and Independent Companies in the Yiddish Theatre of Buenos Aires (1930-1960)

Paula Ansaldo

“If you can find an enthused theatre crowd 6,000 miles from New York, it means that Yiddish theatre still has a future.” 1 With these optimistic words, Maurice Schwartz describes his impressions of performing for the first time in the Yiddish theatre of Buenos Aires.

In 1930, Buenos Aires was becoming one of the world’s main centers of Yiddish culture and theatre. Although the “official” beginning of the Yiddish theatre in Argentina dates to 1901, with the premiere at the Doria Theatre of El Tartamudo/Tsvey Kuni-Leml by Avrom Goldfaden, the flourishing of Jewish theatre dates to the interwar period, when a large population of Yiddish-speaking Jews settled in Buenos Aires, escaping difficult living conditions and anti-Semitism in Europe.

At the same time, Yiddish theatre audiences in the US were declining, so actors increasingly toured to countries where theatre in Yiddish thrived, as was the case in Argentina. The southern hemisphere’s inverse seasons had the extra advantage that American actors on their summer break in the US could work the winter season in Argentina without quitting their home companies. Once in Argentina, they also traveled to cities such as Rosario, Córdoba, and Santa Fe, and to Jewish colonies like Moisesville and Basalbilbaso, as well as other Latin American cities like Montevideo, Santiago de Chile, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro.

Between 1930 and 1950, there were four theatres in Buenos Aires that presented plays in Yiddish on a regular basis: the Soleil and the Excelsior (in the Abasto), the Mitre (in Villa Crespo), and the Ombú (where the AMIA is today). In addition to the theatres, cafes like the Cristal and the Internacional also presented Yiddish vaudeville numbers. Shows were performed from Tuesday to Sunday, with two or even three performances on the same day on weekends. The season normally lasted from April to November, and theatres always played to full houses.

Commercial Yiddish Theatre and the Star System

In a testimony published in 1985, Salomón Stramer, a renowned Jewish actor, singer, and businessmen, said: “As impresarios, we wanted to have two things at the same time: responsibility in the biznes and good repertoire, a contribution to the culture.”

2

This quote synthesizes the difficulties that the commercial Yiddish theatre faced in Argentina: the contradiction between the search for profitability, and the desire to stage plays of artistic value.

In the commercial theatre in Buenos Aires, impresarios brought stars from abroad to lead their companies, and filled out the cast with local actors. Foreign stars could guarantee the success of the season and were perhaps the only way in which the Jewish theatre of Buenos Aires could survive. Some, however, blamed the star system for inhibiting the emergence of a local Argentine-Jewish theatre.

Thanks to this system, many renowned artists arrived in Argentina, and were acknowledged as such even outside the Jewish theatre community. Argentine critics rarely mentioned that actors like Jacob Ben-Ami, Maurice Schwartz, and Joseph Buloff—whose repertoire and acting style were completely different from the operettas, melodramas, and light comedies that prevailed in the theatres of the period—were performing in Yiddish. Instead, they focused on their acting skills and abilities, and referred to them as figures of universal theatre, regardless of the language used on the stage. Many actors in the non-Jewish theatre also went to see Yiddish plays; the Italian-born film and stage actor Silvia Parodi said of Ben Ami:

“Ben Ami has the gift of making himself understood without the need for language… even without understanding a letter of the text, it’s enough to contemplate his face to feel all the passions and feelings reflected. Silence, attitudes, gestures, say so much that there is no need for more in order to understand and admire him.”

3

These Jewish actors were also honored by the Sociedad Argentina de Actores (Argentine Actors Association) and were received in the Casa del Teatro (Theatre House). Some of them were even invited to direct national companies, as was Maurice Schwartz, who in 1942 directed the musical comedy Esta noche filmación (Filming Tonight) at the Casino Theatre, where he directed Tita Merello, one of the most important Argentine actresses at the time. He also staged a Spanish version of Der dibek, by Sholem An-sky. Jacob Ben-Ami starred in a Spanish-language Argentine film in 1949 called Esperanza (Hope) by Francisco Mugica and Eduardo Boneo, in which he played a Jewish gaucho.

Audiences entering the IFT Theatre. Source: Archivo Teatro IFT, Centro Documental y Biblioteca “Pinie Katz” (CeDoB “Pinie Katz”).

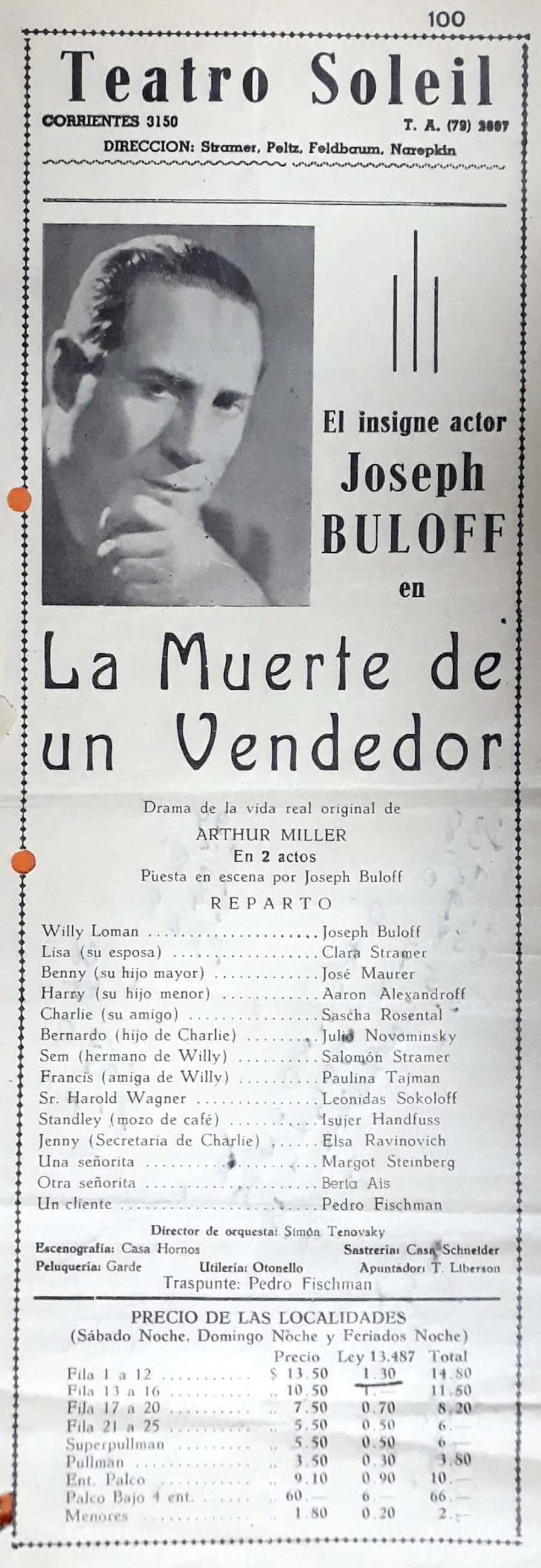

For Argentina, the Jewish theatre was a significant phenomenon, especially when the actors brought repertoire that was unknown in the Buenos Aires theatre scene. Joseph Buloff’s Death of a Salesman/Toyt fun a seylsman premiered in Buenos Aires in 1949 at the Soleil Theatre. This was the first time that the Argentine public saw Arthur Miller’s play. The show was such a success that in 1950, the prominent actor Narciso Ibañez Menta (1912-2004) premiered a Spanish version of the play. This event is emblematic of the Yiddish theatre’s operating as a modernizing force that deeply influenced the larger theatre scene of Buenos Aires. Its itinerant nature, and the genuinely international language of Yiddish, brought radical theatrical ideas, modern aesthetics, and a new repertoire that had not yet been translated into Spanish or developed before in Buenos Aires’ theatres.

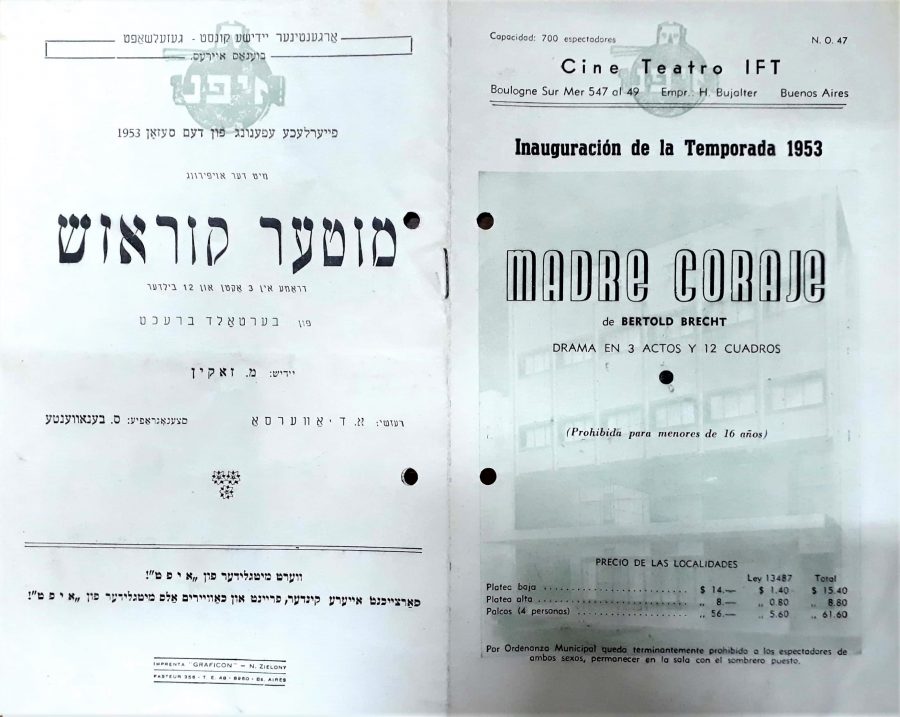

We can find more examples of this in the independent Jewish theatre companies, like the Idisher Folks Teater (IFT), an innovative Buenos Aires company. Their artistic director was David Licht (1904-1975), a Polish actor and director who had been part of the Vilna Troupe and PYAT (Parizer yidisher avangard teater - Parisian Yiddish avant-garde theatre). Licht brought to the company a realistic acting style through Stanislavsky’s theories, which were practically unknown in Buenos Aires at the time. The IFT also staged the first Bertolt Brecht play to premiere in Argentina (Madre Coraje/Muter kurazh). This way the IFT introduced authors and theories that a few years later, would become central to the Buenos Aires theatre scene.

Two countervailing tendencies existed in the Jewish theatre of Buenos Aires: one of art theatre, based on literary works that addressed serious topics, and which attracted non-Jewish artistic circles; and a popular theatre, comprising operettas, melodramas, and vaudevilles, whose purpose was to entertain, and which was not normally reviewed in the non-Jewish press. This distinction between serious and light dramas was not a local conception, but replicated an opposition that existed in Yiddish theatre since the early twentieth century: kunst teater vs. shund teater, or high culture vs. low.

In Buenos Aires, Ben-Ami, Buloff, and Schwartz were considered promoters of kunst teater by the local Jewish intelligentsia, who believed that these actors could be a beneficial influence on the local, predominantly shund theatre. At the same time, the intelligentsia were deeply concerned about the Argentine Jewish theatre’s dependence on foreign stars. Shmuel Rozhanski (Samuel Rollansky) from Di idishe tzaytung, and Jacobo Botoshansky and L. Zitnitzky from Di presse, persistently warned the Jewish theatre community about the dangers of the star system.

Placard of the film Esperanza starring Ben-Ami.

Botoshansky often accused the impresarios of an unreasonable attachment to foreign stars, even as Argentina had enough good local actors to make a permanent theatre. He also complained about the repertoire that the stars brought to Buenos Aires, either because they staged plays that had already been performed in previous seasons, or because the topics that the plays addressed had nothing to do with the specific Argentine Jewish experience. This was because in most cases, the stars brought their New York repertoire, “tailored to the New York public,” which suited the local Argentine needs like “a dwarf a giant’s coat.” 4 And in Rollansky’s words:

“While journalism and literature live from their own local elements, I cannot say that the Yiddish theatre of Buenos Aires can even exist for a few months with the local actors that we have. It always requires the visit of foreign actors. The curious thing is that some local actors outweigh certain stars for their talent, and yet this phenomenon persists. Thus, the history of our theatre is the history of the stars who have performed on the Buenos Aires stage.” 5

This distinction between a true Argentine-Yiddish theatre and a Yiddish theatre in Argentina persists in those years. A large part of the theatre community considered that it was not enough to have theatre performed in Yiddish in Argentina, but was necessary to develop a local Argentine Yiddish theatre.

This polemic was such that there were even “trials” to decide if the star system was beneficial, or if it was an obstacle for a local theatre’s emergence. In one of these trials, the impresario Adolfo Mide: “Don´t ask me, ask the audiences if they would come to my theatre if I didn’t bring stars.” 6 Mide’s response reflects the significance that the public attached to “names and faces.”

Another problem was that since the impresarios wanted to make the most of the foreign stars during their stay, they demanded that new plays be performed every week. In his first season in Buenos Aires in 1930, Maurice Schwartz stayed ten weeks and staged thirteen different plays. Buloff, in his second season in 1934, stayed eight weeks and staged nine plays. This was not only bad for the artistic quality of the plays; it was especially bad for the local artists. Unlike the stars who played roles that they already knew, the Argentine actors were compelled to prepare several different characters with extremely short rehearsal time.

But the problem was not only artistic, but economic: local actors lacked economic stability, as they depended on touring stars. For this reason, in 1932 local actors instituted an actor’s union, the Idishn aktiorn fareyn, in Spanish: Sociedad de Actores Israelitas en Argentina.

The Fareyn statute established a number of rules for impresarios that were intended to limit the stars’ monopolies and to improve the working conditions of theatre employees. A minimum salary was established, and a minimum number of cast members—twelve. It also required that local actors’ contracts had to be signed for at least six months, while foreign stars’ contracts could not exceed three months. Companies were also not allowed to hire more than three foreign stars per season. Regulations also stipulated that a percentage of foreign stars’ salaries had to be paid to the Fareyn. This guaranteed that at least part of the profits of the Argentine Jewish theatre was used to improve the working conditions of local artists.

With the success of the Fareyn regulations, rising antisemitism in Europe, and later, the war, many of Buenos Aires’s former guest stars began settling in Argentina. Among them were singers and actors such as Max Perelman and Guita Galina, Salomón and Clara Stramer, Israel and Ana Feldbaum. Many of these actors became impresarios as well. In 1945, the Soleil Theatre, until then managed by the American lawyer Charles V. Groll (Jennie Goldstein’s husband), became the Empresa Soleil, run by the actors Salomón Stramer, Mauricio Peltz, Israel Feldbaum and León Narepkin. The Soleil tried to position itself as a theatre of good artistic level and a higher quality than its competitors (such as Teatro Mitre, in which melodramas and operettas prevailed). However, the Soleil, like the rest of the commercial Yiddish theatres of Buenos Aires, continued to depend on the visits of foreign stars to sustain their theatre season.

Toyt fun a seylsman/La muerte de un vendedor (Death of a Salesman) playbill in SpanishSource: Fundación IWO, Buenos Aires.

The Independent Jewish theatre: the Idisher Folks Teater (IFT)

The only Buenos Aires theatre company that was not built around the star system and performed on a regular basis was the IFT (Idisher Folks Teater or Jewish People’s Theatre). Like many Jewish art-theatre companies that emerged from amateur groups, the campaign for a kunst teater in Buenos Aires was carried out by members and intellectuals gathered around the IDRAMST (Idishe dramatishe studye or Jewish Dramatic Studio). This amateur theatre group was created in 1932 by members of Jewish workers’ clubs who wanted to make plays that could respond to the needs of the Jewish masses. Later, IDRAMST became a permanent Jewish theatre, and in 1937 changed its name to IFT.

The IFT’s goal was to build a theatre company of local actors that would have a strong aesthetic and political commitment. They agreed with theatre critics’ negative diagnosis of the condition of the Jewish theatre in Argentina, due to the absence of a kunst teater. They believed that in order to sustain an art theatre it was essential: 1) to be free of the star system, creating instead an ensemble; 2) to stage new and original literary plays; 3) to have professional directors, who could bring modern artistic concepts to the Jewish stage; 4) to build a solid financial base for the economic support of the theatre.

In 1936, a Committee “pro Teatro Popular Israelita en Buenos Aires” (for a People’s Yiddish Theatre in Buenos Aires), was established to gather funds for a permanent theatre. In their publications, the campaign appealed to anyone who considered themselves supporters of kunst teater: “friends of the art theatre,” or “lovers of a better theatre.” The committee called for the Jewish population to support the theatre and thus fulfill “a great duty towards Jewish art and culture.” Supporting the IFT was analogous to collaborating with the only theatre that could raise the level of Jewish culture in Buenos Aires. In 1936, the goal was to achieve 500 members. By 1957, that number would reach 5,000.

Membership entailed monthly contributions that freed the company from complete dependence on ticket sales to maintain themselves financially. The IFT’s independence from box office demands was one of their fundamental and non-negotiable principles. Only this way could they take artistic risks and bring new aesthetics and authors to the stage. By developing a membership system, they created the figure of the iftler: a person who supported the institution, and through that support, became part of it. The membership system reinforced the idea that the construction and sustenance of a permanent Jewish theatre in Buenos Aires had to be a common goal of the entire Argentine Jewish community.

A good example of the importance that Jewish Buenos Aires attached to the theatre was the campaign for the construction of an IFT playhouse. By the mid-40s, the need for a dedicated space had become clear; in 1945 the IFT began a campaign to gather funds, and in 1947, construction began. By 1952 the building was finished and the IFT became the first and only Jewish company in Buenos Aires to have its own theatre.

Once the building was opened, the IFT initiated new activities to satisfy the broader cultural needs of the community. They organized music concerts and conferences every week, and over the years added a drama school, a choir (named for I.L. Peretz), a library, a cinema club, a ballet and a theatre school for children, a puppetry collective, an art gallery, and even a chess club. The IFT was more than a theatre: it was a cultural center.

Over the years, the theatre became so firmly established in Buenos Aires that it began to perform in Spanish, which replaced Yiddish as the company’s formal language in 1957. The first Spanish-language play presented was El diario de Ana Frank (The Diary of Anne Frank), which was a huge success. Until 1966, when the permanent cast was dissolved, most IFT plays were performed in Spanish, but the company continued to define itself as a Jewish theatre.

Many things figured in the decision to replace Yiddish with Spanish. First of all, while the IFT achieved independence from impresarios, from box office bottom lines, and from the star system, it was not independent of the Communist Party. Most of the IFT were affiliated with the PCA (Partido Comunista Argentino/Argentine Communist Party) and were also leaders of the Argentine branch of the YKUF (Idisher Kultur Farband or Jewish Culture Association), which unified left-wing Jewish institutions in Argentina. 7 Scholars who have studied the history of YKUF in Argentina argue that in the late 1950s, YKUF started a campaign to replace Yiddish with Spanish in all its institutions. 8 They were accused by the Communist Party of staying in a “Jewish ghetto,” which prevented them from reaching the broader working class. Attachment to Yiddish was seen as an obstacle to integrating with the rest of Argentine society.

Additionally, the use of Yiddish on the IFT stage factored in younger, native Spanish-speaking audiences’ disconnection from the theatre. The theatre’s mandate to extend their ideological influence on new generations of Jews forced them to abandon the language of the older ones. As noted in a 1957 article from their journal, Nay Teater:

“The IFT cannot close its eyes to the changes that have taken place in the Jewish community after so many decades of acculturation on Argentine soil, nor to remain isolated from national culture. Therefore, while continuing to cultivate the highest and most universal manifestations of Yiddish culture, its entrenchment in Argentine life and the needs of new generations who no longer speak the mother tongue have made imperative the use of the common language of all Argentine people on the IFT’s stage.”

Muter kurazh/Madre Coraje (Mother Courage [original: Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (Mother Courage and Her Children)]) bilingual playbill. Source: Archivo Teatro IFT, Centro Documental y Biblioteca “Pinie Katz” (CeDoB “Pinie Katz”).

Not only was the Yiddish audience decreasing, but there were fewer young actors who were able (or wanted) to perform in Yiddish; already integrated into Argentine society, they wanted to make plays that could reach a wider audience. Performing in Spanish also allowed them to become a significant part of the Independent Theatre Movement, which by the 60s was already in its golden age. In 1955 the IFT became part of the FATI (Federación Argentina de Teatros Independientes or Argentine Federation of Independent Theatres). Like the Communist Party pushed the YKUF to replace Yiddish with Spanish, the FATI pushed the IFT to become a Spanish-speaking theatre, so that it could contribute better to the Federation’s goals.

Replacing Yiddish with Spanish was a painful decision for the IFT. But they were a people’s theatre in the broadest sense. They truly believed in the words of Peretz, inscribed on the IFT’s walls: “teater, a shul far dervaksene,” the theatre as a school for adults. Performing in Spanish was the only way to remain faithful to their original mission: to educate the people and to build a better world through culture. When the Jewish masses spoke in Yiddish, the IFT put them in contact with a better and more meaningful theatre performed in their own language. In the 60s it was the opposite: to transmit Jewish culture and political values it became necessary to perform in the language of all Argentines. As Luis Goldman explained in Tribune, the YKUF newspaper:

“To attract a young audience, the faithful, older members must understand the new generations and accept their idiomatic difference, their different way of being. Let Mendele, Sholem Aleichem and Peretz speak in Spanish if Yiddish is no longer understood. Let them speak in any language, since that is the fundamental need for the construction of socialism.” 9

Salomón and Clara Stramer in Teatro Nuevo. Source: Yiddish theatre collection, Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library.

From 1957 until 1966, the IFT performed most of its plays in Spanish. The repertoire included works by Sholem Aleichem, Brecht, Chekhov, and Arthur Miller, as well as Spanish-language plays by Argentine Jewish dramatists, such as Germán Rozenmacher and Osvaldo Dragún. In these years, the IFT became a theatre of great relevance in the national scene, as well as a providing a place of reference for left-wing Jewish and non-Jewish youth.

Nevertheless, when the IFT abandoned Yiddish, it began to lose its position in the Jewish community itself. In the 60s, the loss of its Jewish members was an irreversible process. As a theatre whose financing had never come entirely from ticket sales, when IFT associates decreased, the institution suffered a financial crisis they could never resolve. In 1966, tired of waiting for professionalization, most of the members of the acting collective left to pursue their professional careers elsewhere. That was the end of the permanent theatre company of the IFT.

And what happened with the rest of the Yiddish theatres? The adoption of Hebrew as Israel’s official language has usually been seen as a turning point for Yiddish theatre in Argentina. After 1948, Hebrew began to replace Yiddish as a second language in Jewish schools, so even fewer young people could understand plays in Yiddish. Lost, too, was Yiddish heymishkayt, the feeling being “at home” that previous generations felt when they attended Yiddish theatre. For the Argentina-born, Spanish-speaking young generation, the Yiddish theatre was the theatre of their parents and grandparents. Its aging actors and outdated stories were no longer something to which the young could relate. As the Jewish literary magazine Patch, observed: “the Jewish public only goes to the Yiddish theatre to accompany the in-laws.” In 1955, they noted too that “every Jew who passes away leaves an empty seat in the Soleil Theatre.” The theatre season became shorter, and the Yiddish theatres started closing: first the Excelsior, then the Soleil, and at last the Mitre.

If you travel to Buenos Aires today, you can still visit the IFT building in the Barrio Once. And during the theatre season, you can even go to the IFT to see a play. It won’t be in Yiddish, but it will be a play performed in a theatre that the Jewish community of Buenos Aires built with much effort, sacrifice and love.

Notes

-

1Letter from Maurice Schwartz cited in Martin Boris, Once a Kingdom: The Life of Maurice Schwartz and the Yiddish Art Theatre (New York: self-published, 2002).

-

2Sara Itzigshon, Ricardo Feierstein, et al., “Salomón Stramer,” Integración y marginalidad. Historias de vidas de inmigrantes judíos en Argentina (Buenos Aires: Editorial Pardes, 1985), 18.

-

3Enrique Feinmann, “Silvia Parodi me habla de Ben Ami,” Revista Comedia 6, núm. 75, 1931, 26.

-

4Jacobo. Botoshansky, “Dos yidishe teater in 1930,” Di presse, January 1, 1931, 26.

-

5Samuel Rollansky, “Dos yidishe gedrukte vort un teater in Argentine,” in Cincuenta años de vida judía en la Argentina, Hirsh Triwaks, ed. (Comité de homenaje a El Diario Israelita, Buenos Aires, 1940), 85.

-

6Adolfo Mide, Epizodn fun yidishn teater, trans. by León Skura, Buenos Aires, 1957.

-

7Founded in Buenos Aires in 1941, the YKUF unified left-wing Jewish institutions in Argentina: schools (I. L. Peretz, Jaim Zhitlovsky, Janus Korchak, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento), clubs (Asociación Cultural y Deportiva Scholem Aleijem, Zumerland, Club Israelita de Avellaneda), and cultural centers (Centro Cultural David Berguelson, Centro Cultural Israelita Dr. E. Ringelblum, Centro Cultural Peretz Hirschbein).

-

8See Nerina Visacovsky, Argentinos, judíos y camaradas: tras la utopía socialista. Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2016; Israel Lotersztain, "La religión judeo-comunista en los tiempos de la URSS. La prensa del ICUF en Argentina entre 1946 y 1957," Tesis de doctorado inédita, 2014; Ariel Svarch, "El comunista sobre el tejado. Historia de la militancia comunista en la calle judía," Tesis de doctorado inédita, 2005.

-

9Luis Goldman, Crisis en la vida judía,” Tribune, January 18, 1957, 5.