Nattily dressed, with a center part and round glasses like Sholem Aleichem, Relkin cut a dashing figure.

Uncle Ed, Yiddish Theatre Impresario

Faith Jones

“My Uncle Ed was a Yiddish theatre impresario,” my friend Martha mentioned casually, as we were busy prepping for an event at our local Yiddish organization.

Wait, what? Uncle Ed, it turns out, was Edwin A. Relkin, and if you look in volume four of the Leksikon fun yidishn teater (Encyclopedia of the Yiddish Theatre), you’ll find a four-page entry on him. Uncle Ed was a big deal.

Edwin is not the name his shtetl-born parents chose for him, but as a stage-struck teen in 1893, when his hero Edwin Booth died, Avrom Relkin reinvented himself as Edwin A. Relkin. The Leksikon tells us he started working in theatre as a teenager, in Chicago and then New York, selling programs and ushering. Later Relkin made himself indispensible to actors and managers, and was taken on as an assistant by various producers, including actor-managers like Boris Thomashefsky, Keni Liptzin, and Jacob Adler, often working in provincial touring arms of their organizations in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh. Finally, in 1912, Relkin was able to set himself up in business in New York as a producer in his own right.

He tended to make an impression on people. It wasn’t just the way he could flatter and cajole the actors, although he was good at that. It wasn’t just the way he talked big, like a caricature cigar-chomping producer who promises everyone that he can make them a star. Joseph Rumshinsky, a figure of such proportions that he was unlikely to be swayed by mere fawning, describes him as a force of nature:

Suddenly, as if dropped from heaven, he appeared in the Yiddish theatre world, blown in on a storm wind, a thin man wearing thick glasses, a soft, black hat like a cowboy, his tie usually loose. In winter, no matter how frosty, he carried his coat, or if he did put it on he let it stream out behind him. He didn’t walk but ran. He didn’t talk but shouted.

Nattily dressed, with a center part and round glasses like Sholem Aleichem, Relkin cut a dashing figure.

Jacob Gordin loved Relkin, Rumshinsky says, because Relkin would split a troupe in two, and set them up in two separate theatres, each showing a different Gordin play. Two royalties in one evening! Of course Gordin loved him. Thomashefsky, on the other hand, had turned against Relkin when he started producing other touring companies in competition with Thomashefsky’s own. He called Relkin “The Hobo from Chicago.” Relkin couldn’t care less, it seems. He still produced Thomashefsky vehicles from time to time, and even produced both Thomashefsky and his ex-wife, now arch-enemy, Bessie Thomashefsky, sometimes in the same season. Business is business.

It might have been better for Relkin if he hadn’t been quite so ostentatious. He got on the wrong side of the Actor’s Union in 1913, running a show with non-union actors at Kessler’s Theatre during a strike. Late one night leaving the theatre, he got beat up. On another night, the show’s star, Mary Epstein, was attacked. The Yiddish press openly speculated that the striking actors had hired the young furrier who got caught and the other gentlemen who evaded capture. The press threw around terms like “gedungene gengsters” (hired gangsters) and “boyanes” (hoodlums).

Relkin’s repertoire varied. He was happy to send stars in their major vehicles on long tours across the US and Canada, and often made better money on tours than on the original New York runs. When he took up management of the Yiddish Art Theatre in the 1932/33 season, he was able to put on some pretty high-end material. His production of Yoshe Kalb was probably his greatest artistic success, and Maurice Schwartz toured extensively in it for a number of years. But Relkin wasn’t fussy. He ran crowd-pleasers too, and at his height managed and produced up to two hundred actors at a time in shows in New York, Chicago, Baltimore, and on tour.

One of the high-end Edwin A. Relkin productions, with Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theatre.

Relkin’s personal habits were the stuff of legend—a legend he actively contributed to by good-naturedly telling the best stories about himself. His lack of Jewish education caused him to consistently hire the wrong number of actors for productions of Lateiner’s Yoysef mit di brider (Joseph and His Brothers)—sometimes too many, sometimes too few, but he never seemed to hit on eleven brothers for poor Joseph. Relkin didn’t rent an office, but kept stacks of notes and telegrams in one of his coat pockets. His other pocket was dedicated to his theatrical scheduler and phone book. He spent evenings working out of the Café Royal, one of the great Yiddish hangouts of the day, shouting into the phone there, to the amusement of all present.

Relkin mostly worked in Yiddish theatre, but he longed for Broadway and sometimes worked in tandem with Broadway producers. Yankev Glatshteyn, the great Yiddish poet, tells a story about Relkin’s work as a “fixer” for Broadway plays trying to reach Jewish audiences. While not the producer himself, Relkin was somehow associated with the team producing a new play, The Jazz Singer, on Broadway in 1925. The play was floundering. Relkin came up with a scheme to run a novelization in installments in the great Yiddish newspaper, the Morgn zhurnal. (Novelizations, believe it or not, were already in use in the silent film era.) The show’s producers would pay the newspaper to run eight installments of the novel based on the play, in the hopes that the Yiddish-speaking masses would then stream to the theatre. Glatshteyn, completely broke and in no position to be picky about paying work, was tapped to write this novelization. But on watching the play and receiving a copy of the script, he realized what an impossible task he had taken on. The play’s action takes place over 24 hours. How on earth was he to stretch this out to eight installments? He created an entire back story for the play, complete with a childhood and dozens of new characters.

And it worked. Relkin told the Morgn zhurnal attendance was so much improved that the producers now wanted… more installments! Poor Glatshteyn had to come up with fourteen episodes in total before he was finally allowed to wrap the story up. Just think: without Relkin, Glatshteyn would never have written the novelization. Without the novelization, the play might have sunk without a trace. Without the play’s success, the movie would never have been made, and who knows when the talkies would have caught on. Certainly a lot less ink would have been spilled in the years since then over the disgrace of Jewish blackface.

Relkin’s first foray into Broadway producing himself was not nearly so happy. A writer named Fritz Blocki had successfully adapted Yoshe Kalb for the English stage in 1933; perhaps this encouraged Relkin to take a chance on a play of Blocki’s called Money Mad in 1937. This in spite of the fact that the play had already opened and failed on Broadway earlier in the year under the title Bet Your Life. Relkin cast the great Yiddish actor Ludwig Satz in the starring role, but to no avail. The play opened and closed the same night. Blocki went on to write for radio and television, and never made it back to Broadway.

Relkin got another shot at Broadway in 1942. With the heyday of Yiddish theatre well behind him, Relkin realized there was a market for nostalgia. In a play called Oy is dus a leben! (Oh What a Life!) the remaining stars of Second Avenue—Jacob Kalich, Anna Appel, Molly Picon, among others—told the story of Yiddish theatre playing sometimes themselves, sometimes earlier actors, in what was billed as “A Musical Cavalcade in Two Acts.” For most of the actors, it was their only Broadway appearance. It ran for a respectable 139 performances.

“What did you think of Uncle Ed?” I ask Martha.

Martha is Martha Roth, a person of considerable accomplishments herself. Martha grew up in Chicago, a big theatre town, and Uncle Ed (actually her great-uncle) would come through once a year on business and to visit his mother.

“He was a figure of tremendous romance to me,” Martha says. “I was stage-struck and entertained faint hopes of Uncle Ed putting me on the stage.”

Alas, Uncle Ed was not interested in children, and he died when Martha was only 14. But starting in 1948, when Martha was ten, she began to be included in Uncle Ed’s theatre outings. On his trips to Chicago he would arrange theatre tickets for everybody: all the aunts and uncles, grandparents, and Martha and her parents. They would disperse to various theatres to see different shows—the older generation usually to Yiddish, the younger ones to English—meeting up after the theatre for a late meal at a place on West Madison called Henrici’s. They might do this two or three times a week when Uncle Ed was in town. “Supper after the theatre! To a ten or eleven year old, in the Midwest, in the 1940s… I was smitten.”

Martha even got to see Maurice Schwartz once. Relkin was by that time Schwartz’s personal manager. The play was in English, but it was probably a Yiddish play in translation. Jewish boy falls in love with a shiksa, scenes of renunciation, forgiveness, and “I don’t remember if she converted or if he gave her up.”

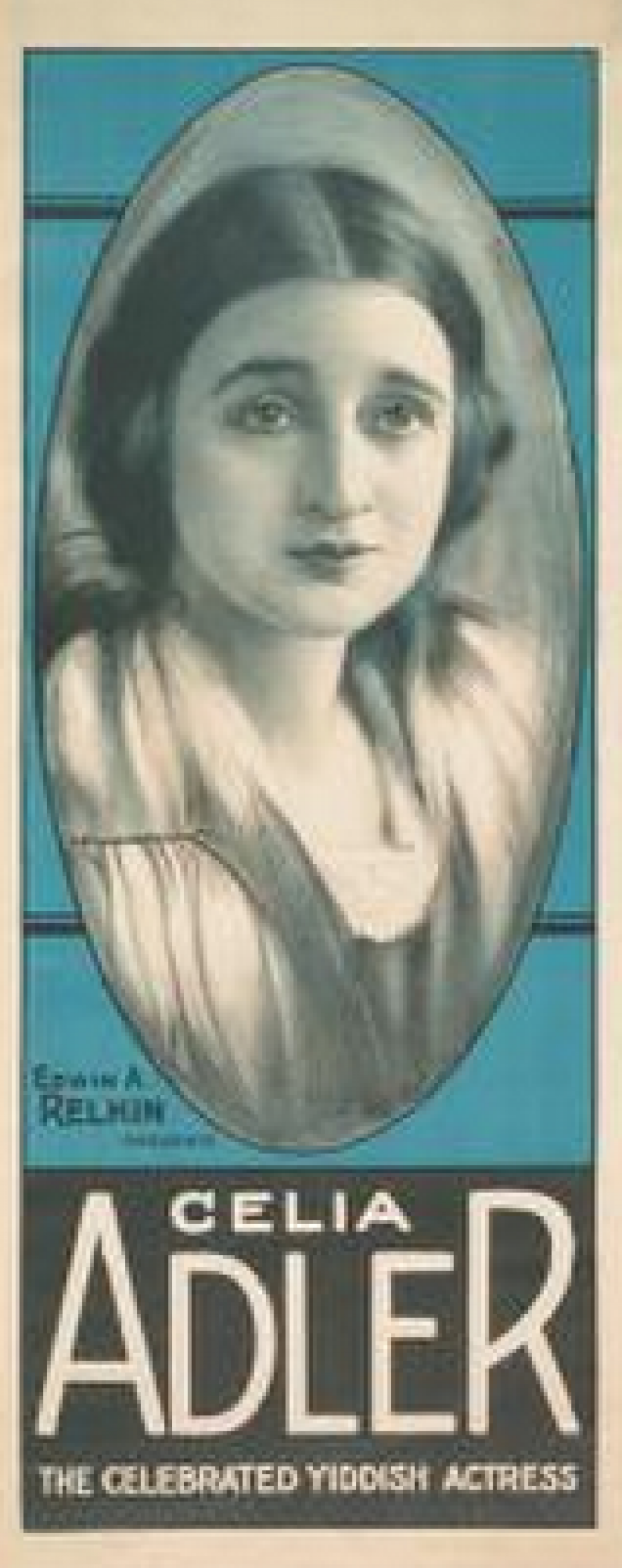

At various times, Relkin represented some very big stars.

Relkin had a rather unhappy personal life for a while, Martha told me. He had married a chorus girl named Dora, and they had two daughters and a son together. Dora was manic-depressive, and when their son died, Relkin left her. He fell in love with another actor, Mignon Hood, and they moved in together in an apartment on the same block as Carnegie Hall. One of Relkin’s daughters, Sylvia, moved in with them, and then Mignon’s son Bill did as well. Relkin and Hood couldn’t marry, because he was still married to Dora, who was by this time living mostly in sanitaria. But Sylvia and Bill did get married, and lived in the Carnegie Hall apartment for the rest of their lives. Neither of them went into the theatre. (Actually, Martha says, “they were both quite boring.”)

When Uncle Ed came to Chicago, Mignon stayed behind. There was no trouble living in sin in New York, but among the family, eyebrows would have been raised. Uncle Ed stayed in a downtown hotel, slept all day and got up in time for the theatre, then worked all night. When he was bored with Chicago, a telegram would propitiously arrive from New York summoning him home.

Edwin Relkin died in 1952, and the tributes poured in. It seemed inconceivable this bigger-than-life personality had left the theatre for good. The New York Times ran an obituary claiming he ran away from home at the age of 16 to join Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a story that doesn’t appear in the Yiddish sources. That rumor may have gotten its start in a 1917 biographical dictionary that says his first theatre job was with a circus in Buffalo, New York. No doubt Relkin was happy enough to let the story swell as the years went on. The Times obituary also mentioned a number of the major actors he had worked with, among them listing one “Yoshe Kalb.” The Times’ coverage of Yiddish has always been nisht azoy ay-ay-ay.

Martha remembers him fondly, though he never put her on the stage. Still, the glamour of the theatre enlivened her childhood, and perhaps Uncle Ed was a role model in some ways. He made his life just as he wanted it. He dressed as if he were the star, not the bean-counter; was flamboyant in habits, careless of convention, and didn’t take himself too seriously. All in all, a life well lived in the Yiddish theatre.