The Talented Mr Rotblat and His Micrographic Tribute to Jacob Gordin

David Mazower

This is the story behind an exquisite portrait of a Yiddish dramatist. It’s also a story of three strong personalities: a struggling immigrant widow, the playwright Jacob Gordin, and a gifted but forgotten artist/photographer; respectively, the portrait’s owner, subject, and creator.

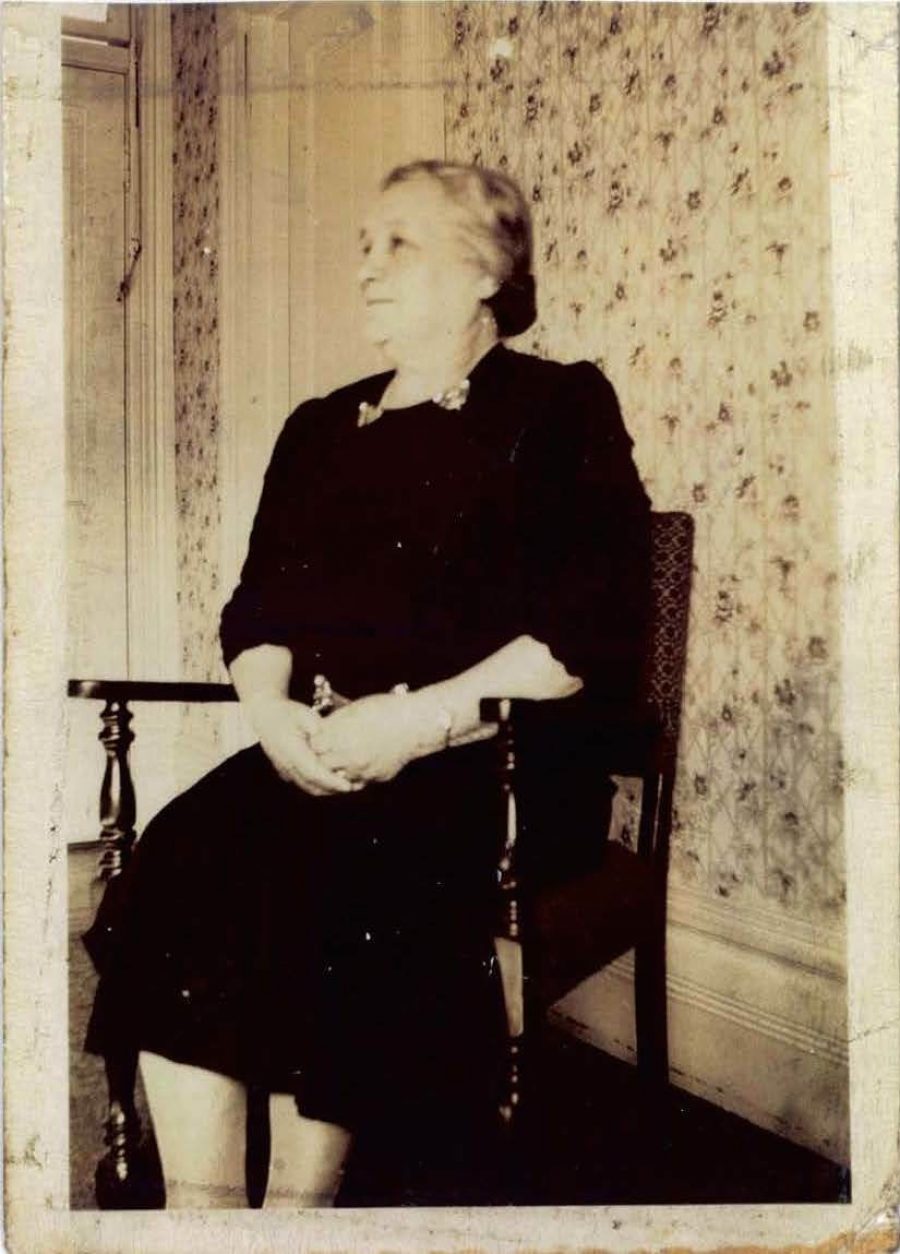

The immigrant widow was Rickel Sazer Hackman. She was born in Brest-Litovsk (present-day Brest in Belarus) in 1884 on the last day of Passover. Rickel came to the US in 1906 to marry Abba Hackman, then grafting a living as a newspaper vendor. In February 1908 Rickel gave birth to their first child, Rosalind. Just over a year later Abba committed suicide, defeated by the harsh economic realities of immigrant life. By then Rickel was pregnant once more, and another daughter, Dina, was born three months later.

Rickel Hackman later in life.

Living in New York as a single mother with two small girls, Rickel somehow made ends meet by renting out rooms and serving meals in her Lower East Side apartment. That’s how she met the portraitist - another newly-arrived immigrant named Louis Rotblat.

Rotblat was born in Warsaw around 1868. He spent a couple of decades living in Britain and his three children were all born in the 1890s in Whitechapel in the heart of London’s Jewish ghetto. By the time of the 1901 UK Census, Rotblat had moved to Manchester and was working as a photographer. A surviving cabinet photo from this time gives his studio address in the city as 171 Great Ducie St.

A portrait photograph by Louis Rotblat that also serves as a Jewish New Year greeting.

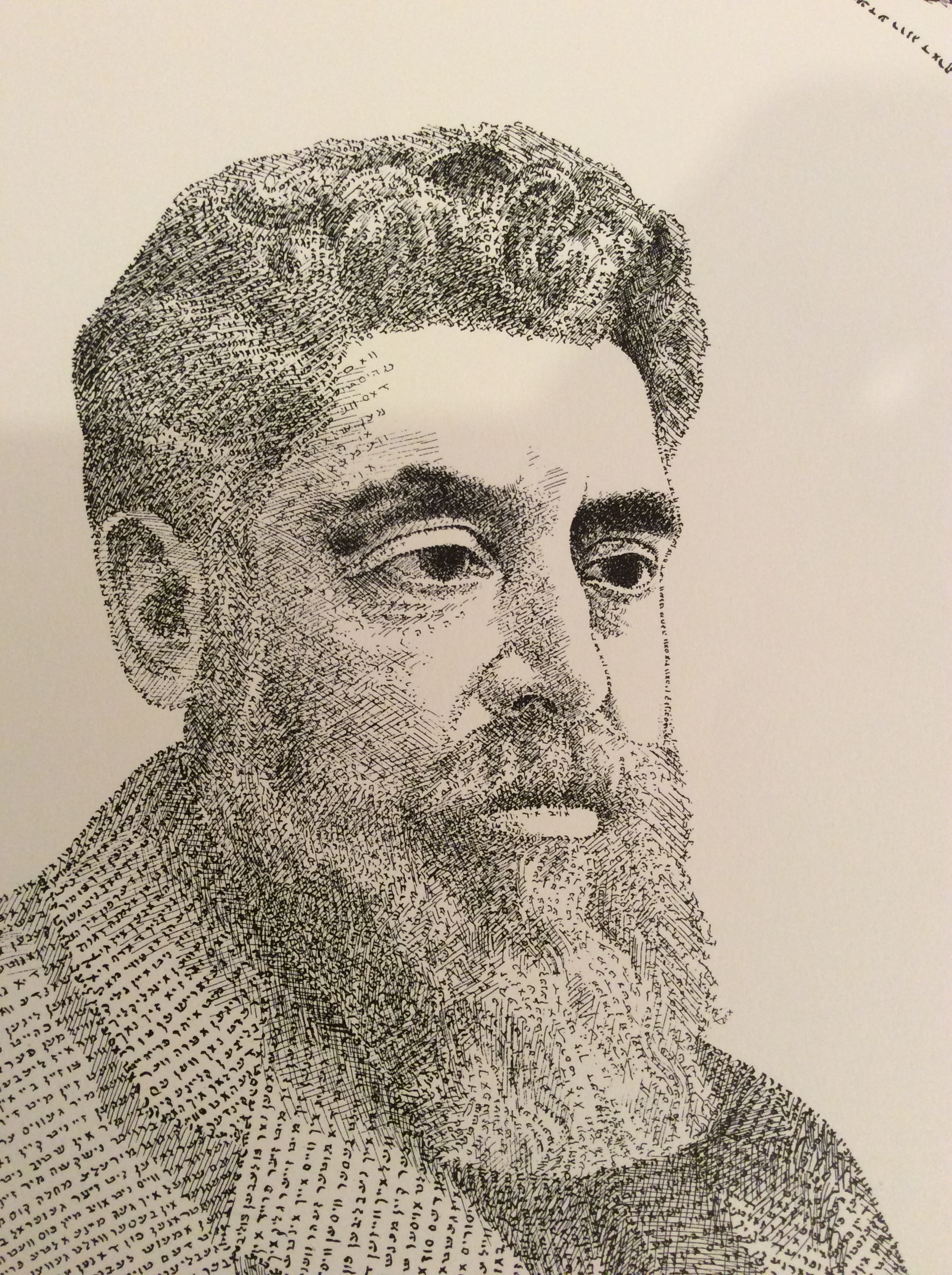

Like many early studio photographers, Rotblat would have needed some of the skills of an artist; he would have been expected to hand-color portraits for his customers, and re-touch photographs to bring reality and fantasy a little closer together. But Rotblat also possessed a much rarer talent. He had a genius for creating micrographs - minutely detailed compositions made up of thousands of tiny letters that appear whole from a distance but fracture and dissolve when viewed close up.

This unique form of Jewish folk art has a long history. It started with the illumination of religious texts, moved on to the depiction of Biblical scenes and portraits (rabbis, monarchs and Yiddish writers) and is still being practised today. A micrographic artist needs the compositional skills of an architectural draughtsman, the fearlessness of a tattooist and the flowing hand of an artist. Plus the fluency and stamina of the sofer, the Torah scribe, the occupation which many micrographers followed.

Rotblat created his first known micrographic portrait in London in 1897. It paid tribute to another famous Yiddish dramatist, Abraham Goldfaden the founding father of the Yiddish stage. The Goldfaden micrograph, another beautiful artwork, uses thousands of words from the text of the Biblical operetta Shulamis, one of the most popular of all Goldfaden plays.It seems safe to assume that Rotblat was not only a fan of the Yiddish theatre, but also closely involved with that world. Buried in the ship’s passenger log that records his arrival in New York in July 1909 is a tiny but significant detail. Asked to provide a ‘name or address of nearest relative or friend in country whence alien came’, Rotblat - travelling under the name Louis Rothblatt - names his ‘brother in law, M. Waxman’, living at Rutland Street in London’s East End.

This is surely a reference to Moyshe Dovid Waxman (1874 - 1931), one of London’s leading Yiddish actor-managers, whose address is listed as Rutland Street in the 1911 UK Census. Let us further suppose that Rickel Hackman took in travelling Yiddish actors as lodgers, and it’s easy to see how the 40 year old artist/photographer might have made his way to her apartment building on his arrival in the US.

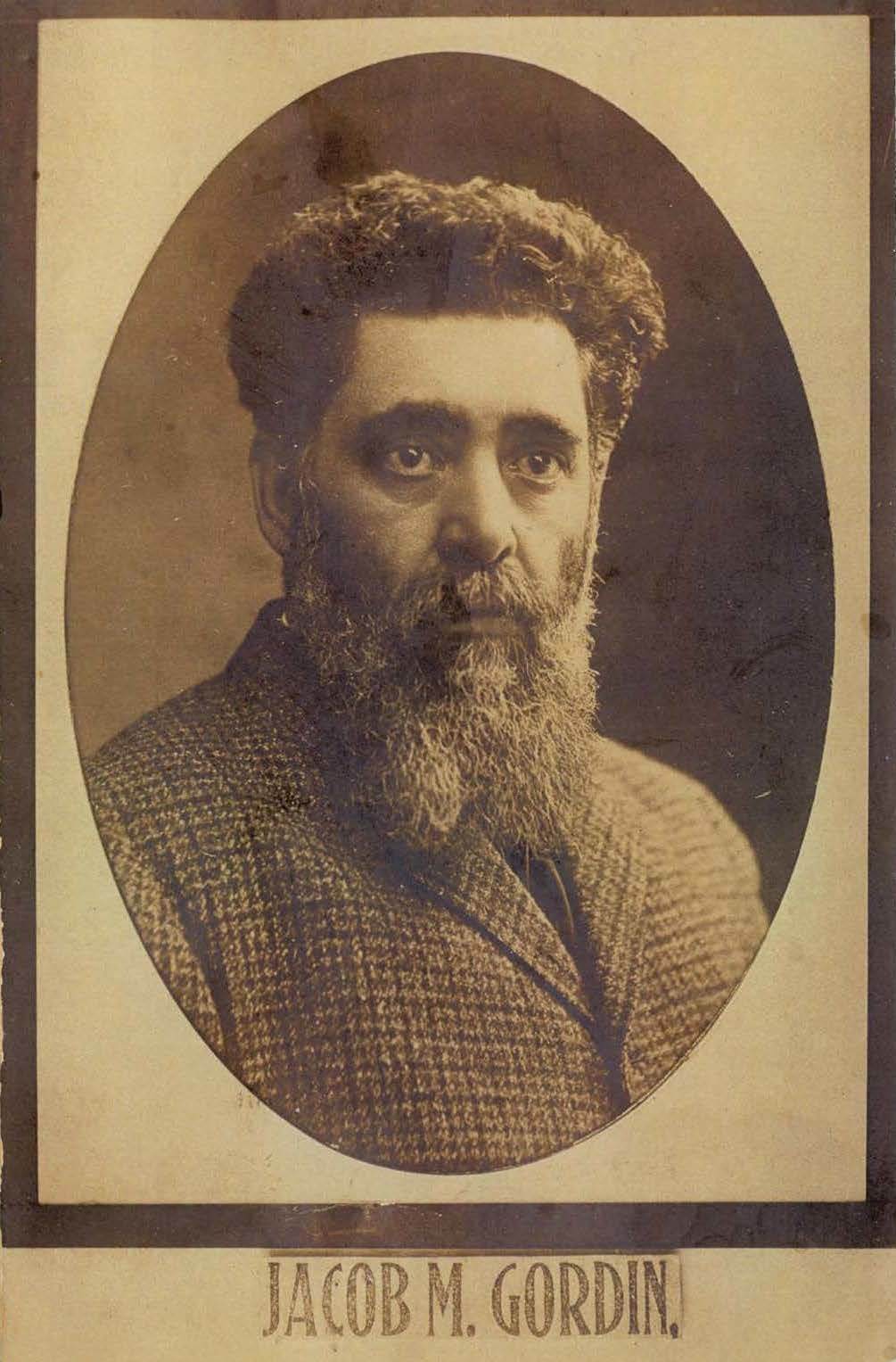

Louis Rotblat arrived in New York in July 1909 just as the city’s immigrant community was slowly emerging from a near-frenzy of communal mourning. Its cause was the untimely death of Jacob Gordin, the great reformer of the Yiddish stage. A majestic figure with jet black eyes and a full beard, Gordin had been cut down in his prime. His death felt like the passing of a Biblical prophet and it sparked a four-day mourning festival of unprecedented proportions. On the day of the funeral, Sunday June 13, 1909, an estimated 200,000 people lined the streets to watch the procession wind its way from Brooklyn to the Bowery, and back again. As the poet Morris Rosenfeld reported:

“Thousands of vendors sold black mourning bands, buttons bearing Gordin’s picture, wreaths and a choice of photographs of the deceased - the healthy Gordin, the robust, the fiery-eyed, the dying Gordin on his death-bed with a compress on his head, and the dead Gordin.”

Most likely Rotblat sensed the commercial potential of an artistic homage to an iconic folk hero. Or perhaps he just felt inspired to create it. In any event, I imagine him working late into the night in a corner of Rickel Hackman’s crowded apartment to create another masterpiece of Yiddish theatre micrography.

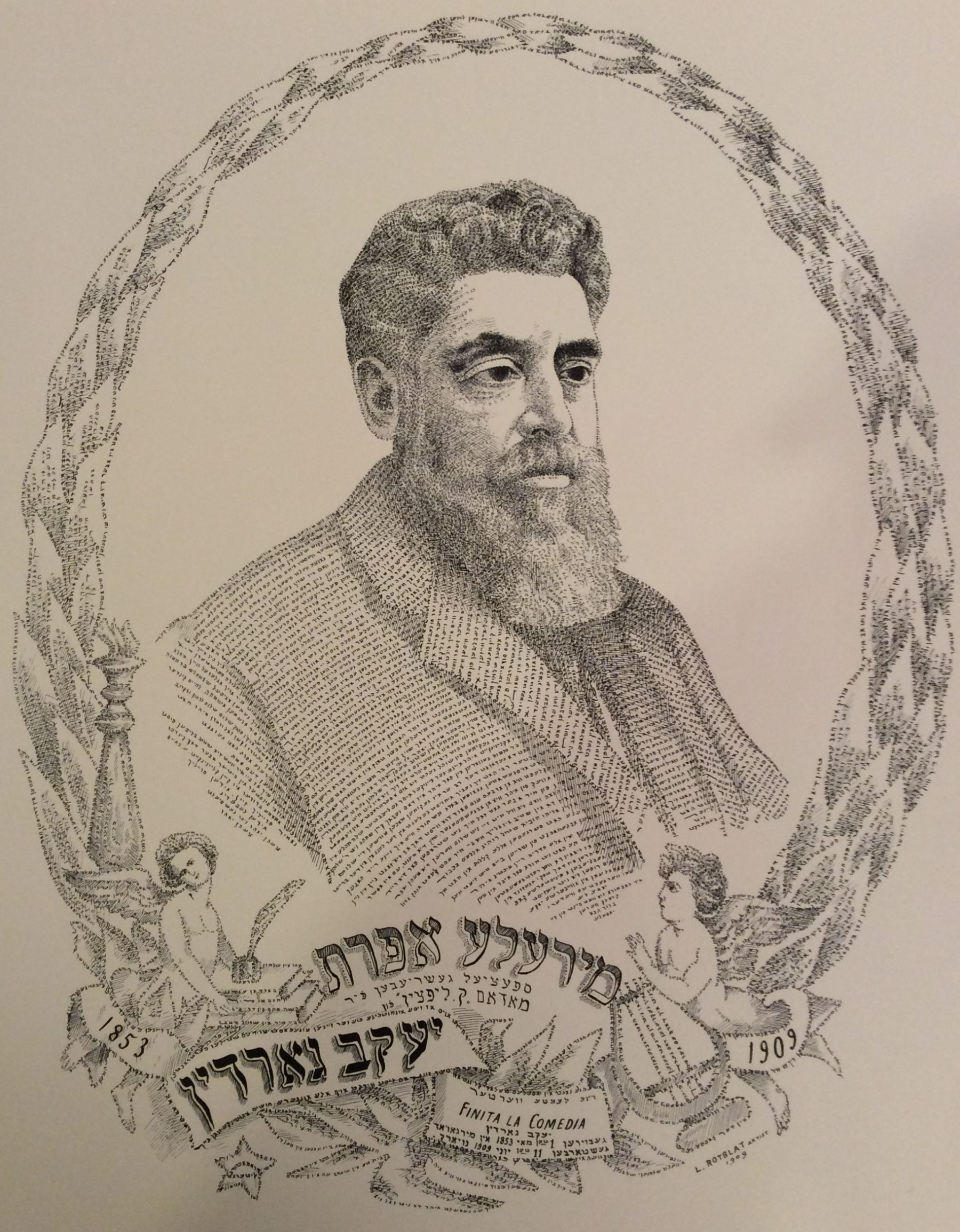

In similar vein to his Goldfaden micrograph, the Gordin portrait was also minutely detailed and was based on the text of a hugely popular play. This time it was Gordon’s Mirele Efros, also known as The Jewish Queen Lear.

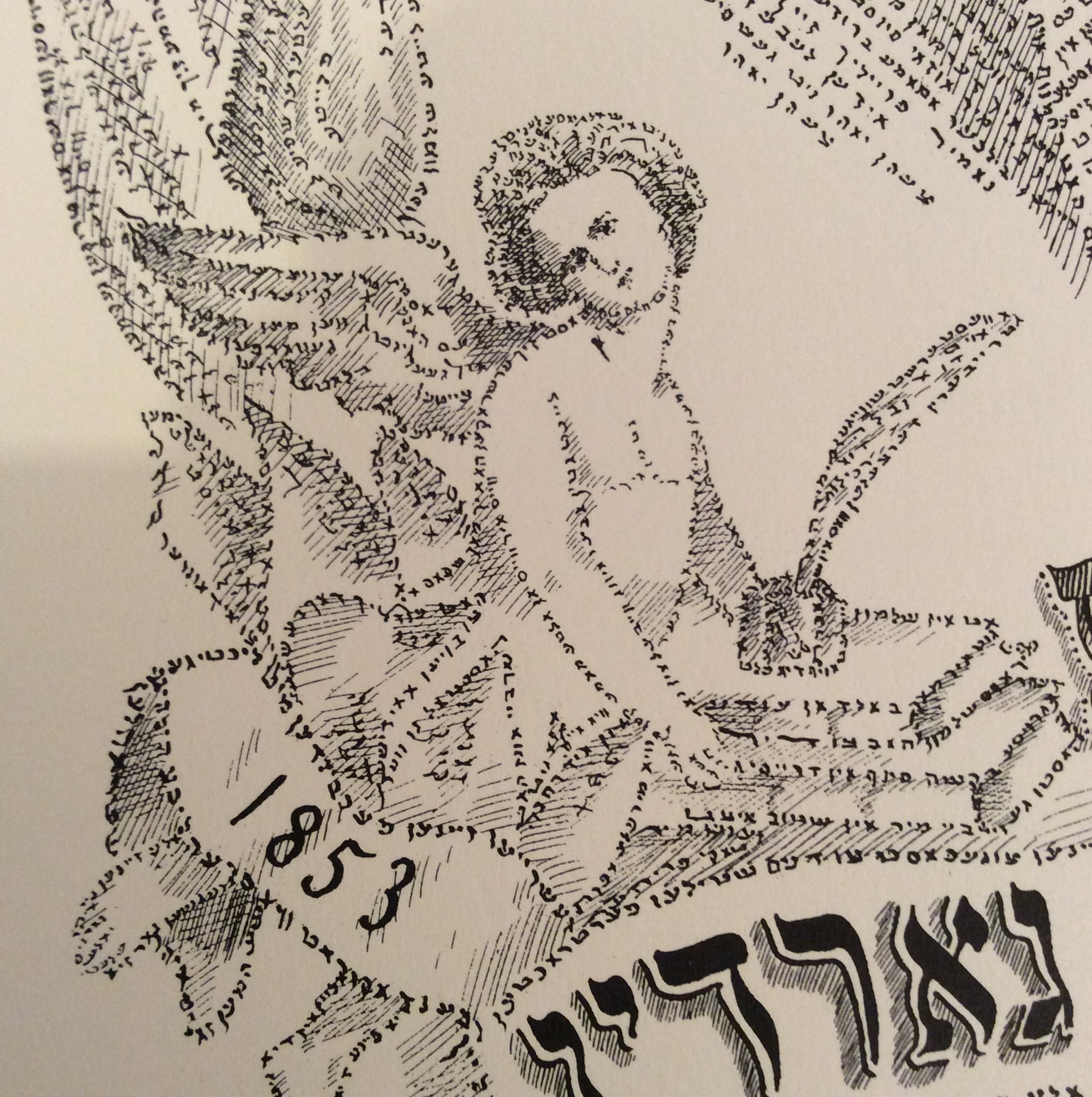

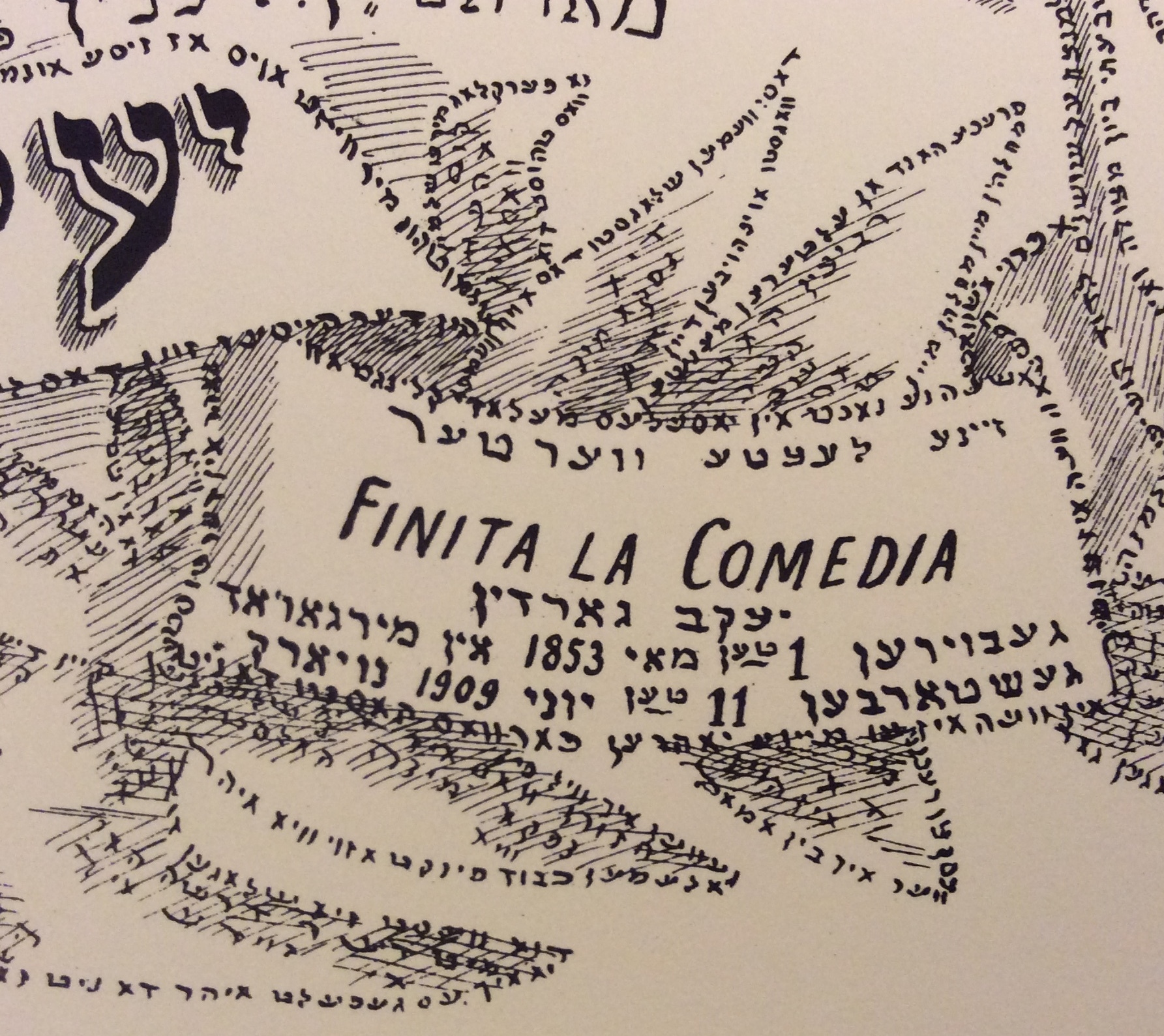

Gordin’s soulful features are centre stage, surrounded by an elaborate wreath. There are cherubs, a lyre, an inkwell resting on two books, and a memorial candle. Rotblat makes a feature of Gordin’s last words, reported to be ‘Finita la Comedia’. He adds the dates and place of the playwright’s birth and death, and signs off with ‘L Rotblat, artist, 1909.’

Many micrographic portraits of that period were reproduced and sold in limited quantities as lithographic prints. We don’t know whether that happened with the Gordin portrait. But we do know that Rotblat’s elegantly framed original artwork remained in Rickel’s hands. Perhaps it was given to her as a present. Or perhaps she accepted it in lieu of rent.

In any event, it stayed with her for the rest of her life…..through her second marriage to Sam Weisblatt in 1917, through the time she ran a dairy restaurant on West 43rd Street (just off 5th Avenue) with her brother, through the birth of several more children in the Bronx, and then during the years she and her husband ran the Vege-Tarry Inn, a vegetarian summer hotel in Berkeley Heights, New Jersey.

The portrait passed to Rickel’s son, Lewis, after her death. He also took good care of it before gifting it to the YIVO archive in New York in 2007. I came across it there and contacted Lewis, who invited me to visit him at his retirement home in New Jersey. He told me the story of his mother’s early years and explained that he had twice made reproductions of the portrait for local fund-raisers: “The first time, a friend of mine made me a hundred full-size copies to sell at a synagogue charity event to raise money. They figured they would sell them for five dollars each. Guess how many they sold? They sold one! Nobody had a clue who Gordin was!” He also showed me some postcards that his mother kept throughout her life. They gave an insight into her cultural world and her politics and included portraits of the radical Yiddish poet Dovid Edelshtat, Russian anarchists Kropotkin and Bakunin, and Catherine Breshkovsky, known as the ‘grandmother of the Russian Revolution’. Also among them was a card of Jacob Gordin with a black border - a memorial tribute from 1909, perhaps even the model for Louis Rotblat’s portrait?

Jacob Gordin Memorial Card, 1909

Close up of Rotblat’s Gordin micrograph

Rotblat died in the Bronx in 1943. His two remarkable portraits of Yiddish playwrights alone give him a strong claim as one of the great modern micrographic artists. But that is far from the sum total of his work. Rotblat’s distinctive lettering marks him out as the artist behind an anonymous 1920 micrographic portrait of the celebrated Yiddish singer Aaron Lebedeff sold recently by the New York auction house Kestenbaum. A few lithographic copies of another elaborate Rotblat micrograph, the Wisdom of Solomon, have also appeared occasionally at Judaica auctions in recent years. But Louis Rotblat’s life story and his contribution to the art of micrography remain almost entirely unresearched, as does the whole remarkable subject of micrography in general.

The great micrographic artists were geniuses of geometry and pattern-making and nowhere is their skill more evident than in the portraits. From jubilee tributes of Queen Victoria and Emperor Franz Joseph, to memorials to Theodore Herzl and tributes to Yiddish writers (including Ansky, Reyzen, Opatoshu, Perets, and Shomer) the portraits are extraordinary in their breadth of subjects and techniques. There’s a wonderful book waiting to be published with reproductions of these unique and quintessentially Jewish artworks. Any enterprising publishers out there?

Acknowledgements:

My thanks to Lewis Weisblatt and his wife Mildred for their generous hospitality and for sharing information about Rickel Hackman / Weisblatt. Moris Rosenfeld’s quote comes from Arthur Goren’s book The Politics and Public Culture of American Jews.