Miriam Karpilove. Courtesy of David Karpilow.

Theatre: A Sketch

Jessica Kirzane

Miriam Karpilove (1888-1956) was a prolific Yiddish writer and editor. She was born in Minsk (now Belarus, then part of the Russian Empire) among the middle of ten children, and immigrated to America in 1905, settling in New York City, in Harlem, the Sea Gate neighborhood of Brooklyn, and later in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where several of her brothers lived. Her first published work appeared in print in 1906 in Idishe fon when she was eighteen years old, and she continued her publishing career until the mid-1940s. Karpilove wrote hundreds of short stories, journalistic reportage, plays, and novels, and served as a staff writer for the Forverts in the 1930s. Her writing appeared in the periodicals Der tog, Di varhayt, Forverts, and Ladies Garment Worker, among others, as well as in book form.

“Theatre” exists, to my knowledge, only as a handwritten manuscript and was never published. Although it’s possible that the story made its way into the hands of an editor, Karpilove kept an extensive list of everything she had ever published, and this story does not appear on the list. 1 Karpilove’s writing tended to be somewhat autobiographical. Toward the end of her life, as she contemplated writing her memoirs, she explained in a letter (in English) to her friend Rose Shomer-Batchelis that “I gave so many parts of me in a number of novels. Now, if I should want to unite the parts, I have to go thru all of them to put it together.” 2 Although it’s unknown if the play that she references in “Theatre” is one that she actually wrote, we do know that Karpilove was a sometime playwright—her earliest major success was her play In di shturm teg (In the Stormy Days, 1909)—and that she did at times turn her attention to current events, including several unpublished manuscripts set in mandate Palestine. This is the first writing that I have read of hers that directly mentions the Holocaust, and it brings to light questions of what it meant for someone who was known as an author of romance literature to try to continue in her craft under the shadow of cataclysmic world events (a question that calls to mind Kadya Molodovsky’s Fun Lublin biz Nyu-york: Togbukh fun Reyzl Zilberg [From Lublin to New York: Diary of Reyzl Zilberg] as well).

Miriam Karpilove. Courtesy of David Karpilow.

The story offers a window into Karpilove’s struggles as a woman in the male-dominated world of Yiddish literature and culture, problems that she explores consistently in her published writing and in her personal correspondence. These problems include expectations about the appropriate genres and subjects for women’s writing (domestic, romance), as well as male editors (and here, directors) not taking her work seriously or looking to take advantage of her. Of particular interest to me is the moment in which the directors suggest that the author enjoyed power and prestige because of her regular position at the Forverts. Karpilove’s letters demonstrate that she aspired to such a position for most of her writing career, feeling that she was shut out of Yiddish publishing because she was not an insider with a staff position. It wasn’t until the 1930s that she attained this role and the stability that regular employment offered, and by the time this story was written she likely had already left the Forverts to live in Bridgeport with her widowed brother. The directors’ insulting insinuations that she does not deserve to be paid because she already has regular employment illustrate the disadvantages that even her short-lived role at the Forverts had, as yet another way that men in positions of power could try to exploit her work.

The story is at once about the business of theatre, and its relationship to Yiddish print culture (the news of newspapers as well as the writers), and is about the theatrical nature of modern Yiddish culture in America, which appears to only be acting as though all is well, while Jews in Europe are living out atrocities. In the story, Karpilove uses her biting wit and her signature ironic tone (a tone she employs in most of her published work, across genres), to depict Yiddish theatre, and Yiddish culture in America in general, as an insincere and irrelevant sham that cannot appropriately speak to the urgencies of its moment.

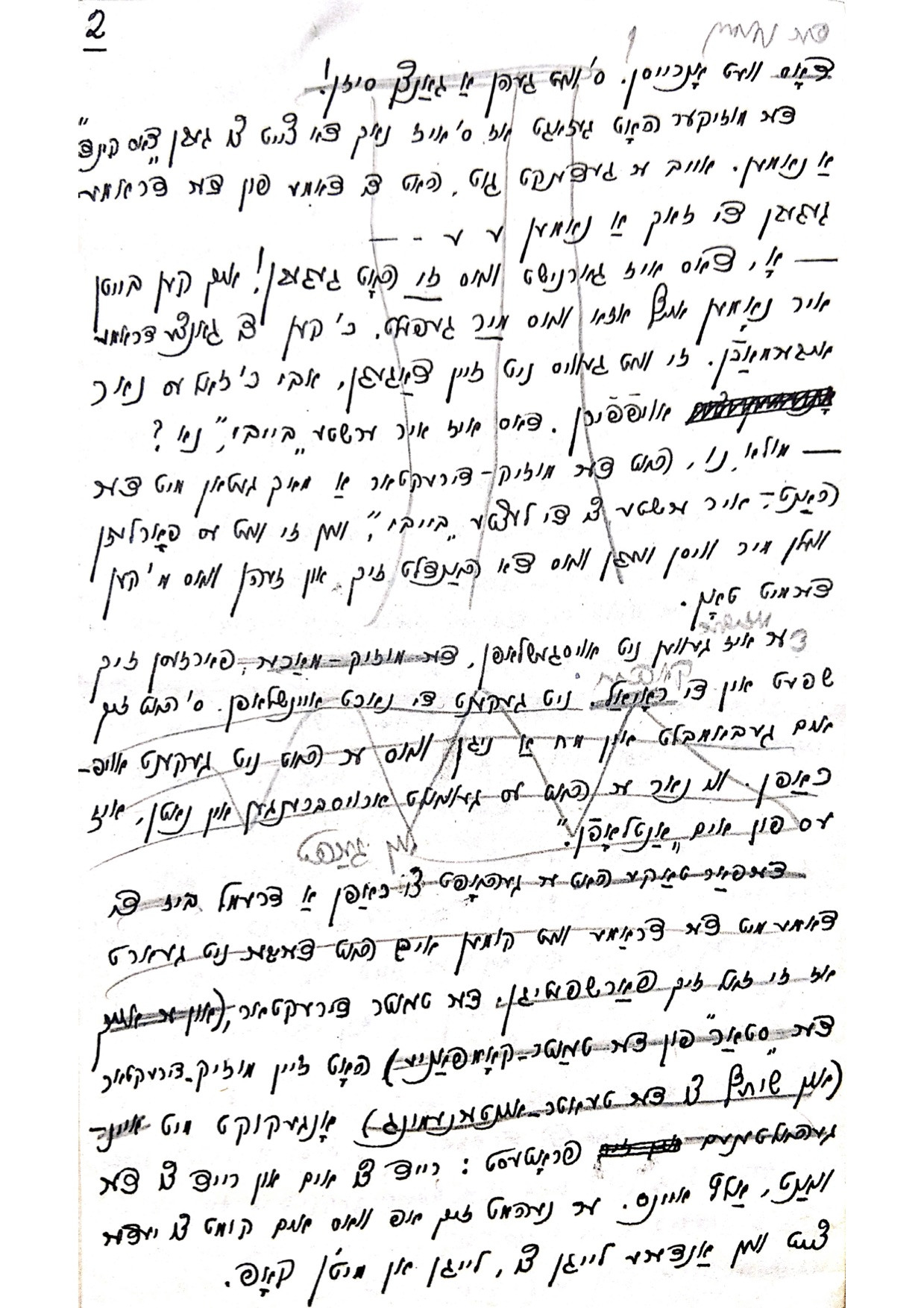

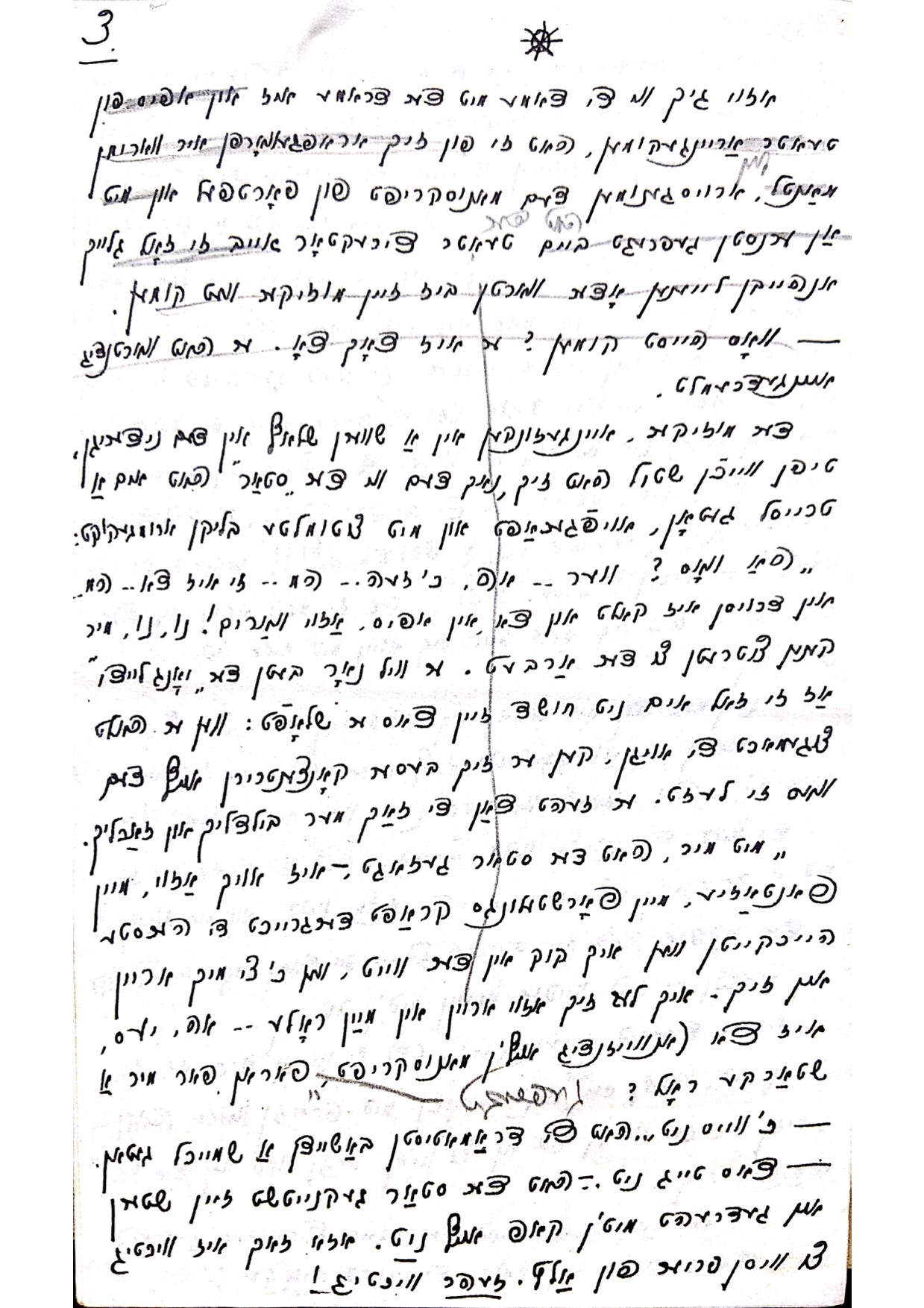

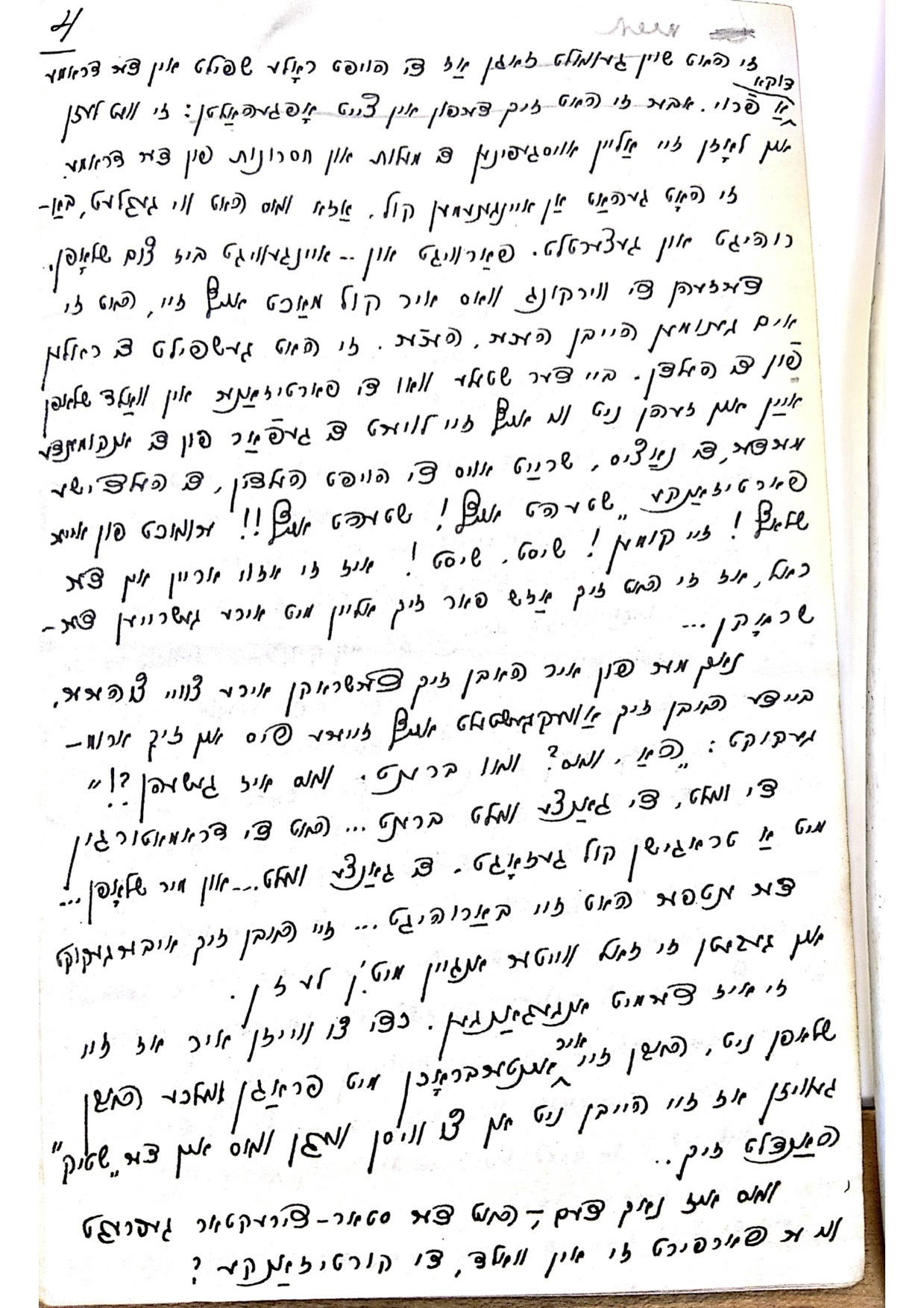

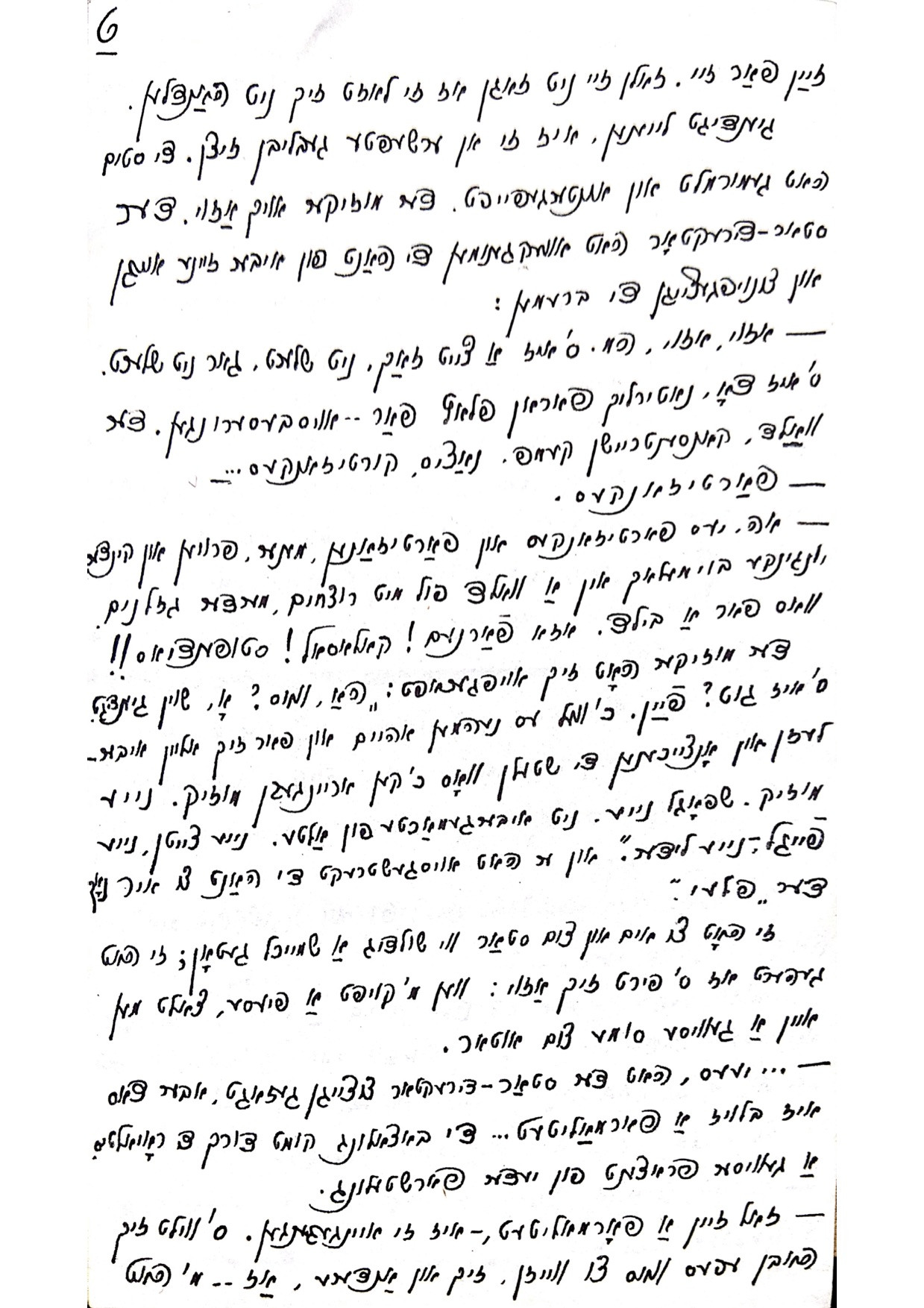

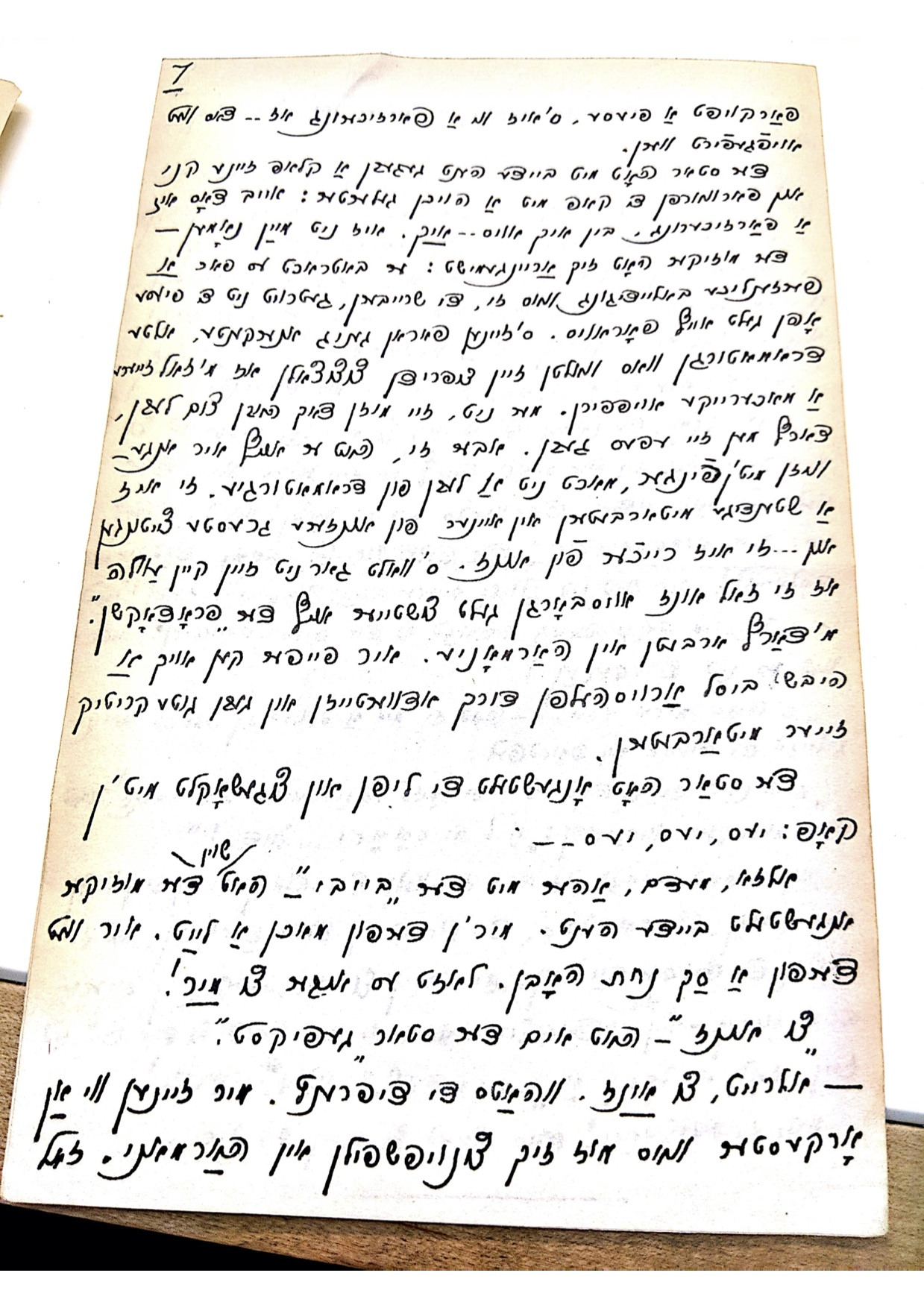

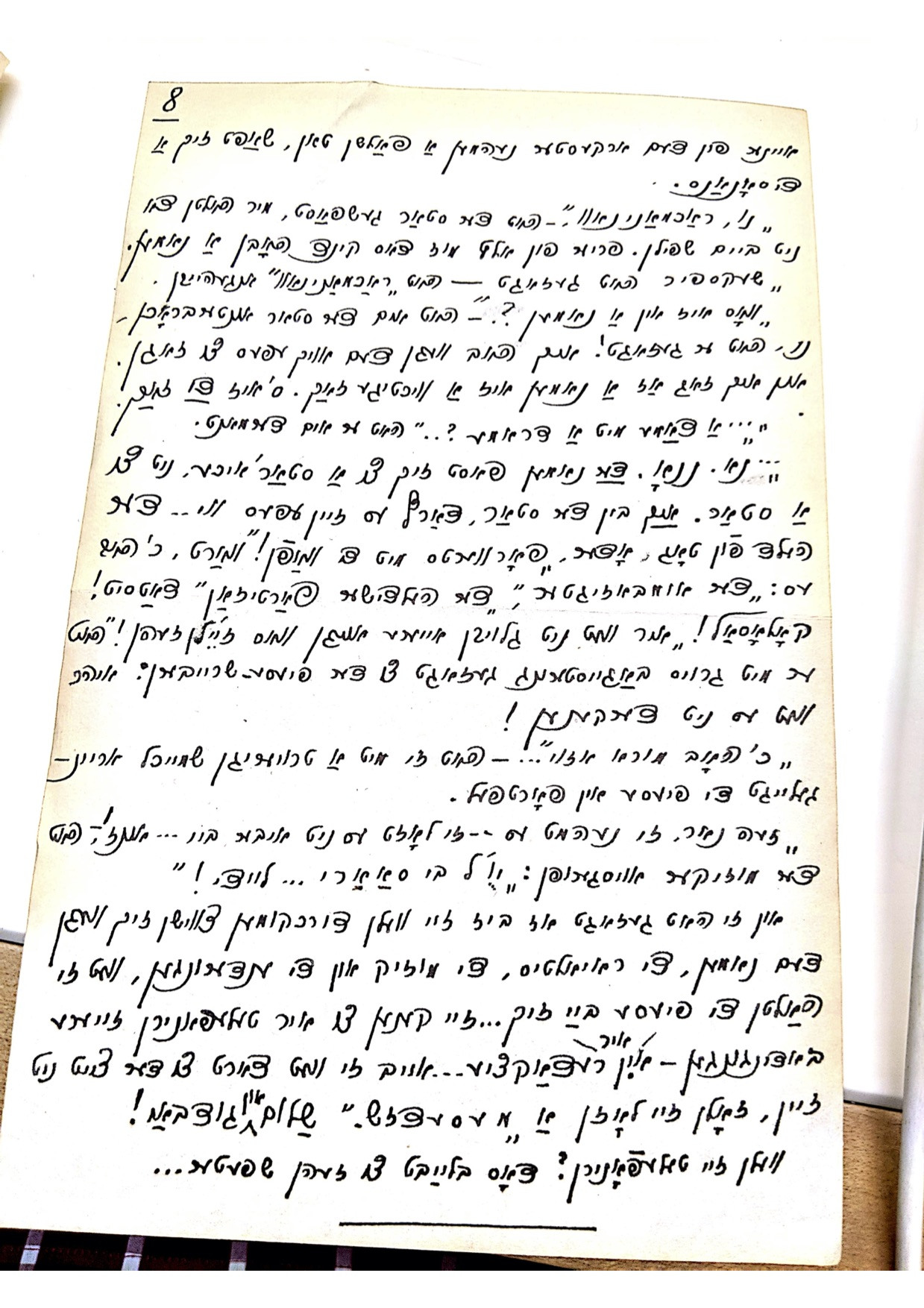

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

Text for “Theatre.” Source: box 2, RG 383, Miriam Karpilow papers, YIVO.

“Theatre”

The director impatiently glanced from his clock to the door of his office. He had an appointment with a young lady who had written a play. The musical director was also there to hear the lady read her play to see how much music he could insert into it and where it would go.

The two theatre men had big plans for how they would make the play happen. They both agreed that the most important elements of any production were the scenery and the music. It was nice if the writing went well with it. And this play would attract more interest because it was written by a woman.

“A Lady with a Play,” muttered the director, who was also the star, with a nasal twang. “That’s what I have here! What a fine name for a play—A Lady with a Play! That sounds like a hit!”

The musical director demurred, saying there would be plenty of time to give the “child” a name. He seemed to recall that the lady had already named the play herself…

“Who cares what she called it? I can change it to whatever I like. I can write the whole thing over if I want to. She won’t object, so long as I agree to put on her play. It’s her first ‘baby’ isn’t it?”

“Unfortunately, no,” said the musical director, shrugging. “Whether it’s her first baby or just her more recent one, we’ll see what the situation is once we let her read her work, and we’ll see what we can do with it.”

The musical director hadn’t slept a wink the night before. He’d been up late with the company, and now he settled down for a quick nap. The director stared at his musical director in protest, but talking to him was as good as talking to a brick wall. There was no use in fighting when that man decided it was time to take a rest, so the director put his head down as well.

When the lady with the play arrived she took her manuscript out of her briefcase. The star director had all but fallen asleep. The musical director, who was fast asleep in a soft, low chair, awoke to the director shaking him. He looked around, confused. “What’s this? Who?…Oh, I see. Ahem…She’s here…heh! It was cold outside, but so warm here in the office…Alright, now let’s get to work!” He told the young lady not to be concerned that he was sleeping—he could concentrate better on her reading by closing his eyes. He could picture it more clearly that way.

“I’m the same way,” said the star director. “My imagination can reach its highest potential when I am more removed, when I enter into myself. I live deep within the roles I play. Oh, yes, is there a strong role in here for me?” he asked, peering into the manuscript.

“I don’t know,” said the lady playwright, with a modest smile.

“That won’t do,” said the star director, wrinkling his brow and shaking his head. “That’s the sort of thing you need to know first of all. It’s very important!”

She explained that the play’s leading role was for a woman. She would read it and let them weigh the merits and flaws of the play for themselves.

She had a captivating voice, calm and gentle, that stroked and rock them to sleep. Seeing the effect her voice was having on them, she raised it higher and louder. She played the role of the heroine. The partisans in the forest were asleep and didn’t see the danger, the murderous Nazis were approaching. The heroine, the heroic partisan, cried out, “Wake up! Wake up! You have to get up! They’re coming! Shoot! Shoot!” She was so absorbed in the role that she seemed to have frightened herself with her screams.

Even more than she, the men who were listening to her were startled. They leapt to their feet and their eyes darted around the room. “Huh? What? Where’s the fire? What happened?”

“The whole world is on fire,” the playwright lamented in a tragic voice. “The whole world is on fire, and we’re asleep…”

Hearing her answer, they calmed down. They exchanged glances and then asked her to keep reading.

She read on. In order to prove to her that they weren’t asleep, they interrupted her with questions that only served to demonstrate that they had no idea what her “skit” was about.

“What happens next?” asked the star director. “What happens after he forces her against a wall? What happens with the courtesan?”

“You mean the partisan,” she corrected him.

“Oh yes, the partisan. She bears his child, doesn’t she?”

“…no.”

“Why not?”

“Because—she refuses!”

“That’s a shame. A child creates such pathos. It can really liven up a play. It’s what the audiences like.”

“And it’s a good place to add some music,” asserted the musical director. “You can have a lullaby or a lament. And what about a dance number in the forest after they beat their enemies, huh?”

“This isn’t an operetta or a burlesque!” the playwright cried. “It’s a tragedy, a memorial to the victims, to the martyrs, to all those who were killed…” She was overcome with emotion and couldn’t say anymore. She placed the manuscript back in its folder and made a move to return it to the briefcase, but the star director stopped her, telling her to calm down. He told her to read the play to the end and then they would talk business. They wouldn’t add anything to the play or take anything away without her permission. Of course some changes would be necessary to make the play appropriate for the stage. Writing is one thing and acting is another. But together, these two things… She has rich material, but it could be improved. It just needed to be polished, refined. Many great, famous professional playwrights allow directors to make changes to their work. Slight alterations that make the work more appropriate for the stage. And she wasn’t willing to do even that? How could that be? Who’s ever heard of such a thing? “So, my dear, read on.”

She read more, without any desire to do so, just so that they wouldn’t be able to say that she didn’t behave herself.

She finished reading. She sat, exhausted. She silently wet her lips. The musical director did, too. The star director removed his hands which he had placed over his eyes and wiped his brow.

“Well, well,” he said. “Hmmm… I see that it’s a current events piece. Not bad. Not bad. There’s, of course, room for…improvements. The forest, the concentration camp, Nazis, and courtesans…”

“Partisans.”

“Oh, yes. Partisans. Lady partisans, and male ones too. Men, women, and children, like young trees in a forest full of murderers and thieves. What an image. Captivating! Colossal! Stupendous!”

The musical director roused himself, saying, “Huh? What? Oh, it’s over. Was it good? Very nice. I’ll take it home so I can look it over myself. I’ll read and note the places where I want to add some music. New music. Brand new, not just rewritten from old tunes. New times call for new music.” He reached out his hands to take the play from her.

She smiled apologetically at him and at the star director. From what she’s heard, when you buy a play you usually pay the author something for it.

“Ye-es…” the star director admitted cautiously. “But that’s just a formality. You get paid based on the results. A fixed percentage of each performance.”

“Even if it’s only a formality,” she insisted. “I’d like to have something to show for it. So would anyone. If I sell a play, having some payment might help assure me that you’re going to put it on.”

The star director slapped his hands against his knees and threw back his head with a loud burst of laughter. “If what you need is reassurance, you have my word.”

The musical director added, “And if that’s not enough, you have mine, too.” He took it as a personal insult that she, the writer, could think of taking money in advance. There are many well-known, experienced playwrights who would be happy to pay to have their work performed. But after all, they need to have some way to make a living, so they have to be paid something. But she—he pointed his finger at her—didn’t make her living as a playwright. She was a regular employee of one of the greatest newspapers and must be richer than the actors themselves. It wouldn’t even be an injustice to ask her to lend them some money so they could put on the production. They should work together in harmony. Her paper also could certainly help by advertising and publishing positive reviews.

The director licked his lips and nodded, “Yes, yes, yes…”

“So, madam, hand over the ‘baby,’” demanded the musical director, stretching out both his hands. “We’ll raise it to be someone. You’ll be very proud. Give it to me.”

“To us,” the star director corrected him.

“Alright, to us. What’s the difference? We’re like an orchestra that must play in harmony. If one of us plays the wrong note, then there’s dissonance.”

“Well, Rachmaninov,” the star director joked, “We’re not playing. First of all, the child must have a name.”

“As Shakespeare says,” “Rachmaninov” quipped, “What’s in a name?”

“Who cares what he said?” yelled the star director. “I have something to say about it too. And I say that a name is important. It’s the most important thing.”

“A Lady with a Play?” the musical director reminded him.

“No, no. That name suggests a lead actress, not an actor. I am the star. It should be something like, The Hero of the Day, or Forward in Arms. Wait, I have it! The Undefeated: The Heroic Partisan. That’s it! Colossal! You won’t believe your eyes when you see it!” he said excitedly to the playwright. “You’ll hardly recognize it!”

“That’s what I’m afraid of…” she said with a sad smile as she placed the play back in her briefcase.

“Do you see? She’s taking it back! She won’t let us have it! You’ll be sorry, lady!” shouted the musical director.

She said that if they were willing to come to an agreement about the name, the royalties, the music, the changes, all their stipulations, they could reach out to her at her editorial offices. If she wasn’t there, they could leave a message for her. “Goodbye!” she huffed.

Will they call her? That remains to be seen.