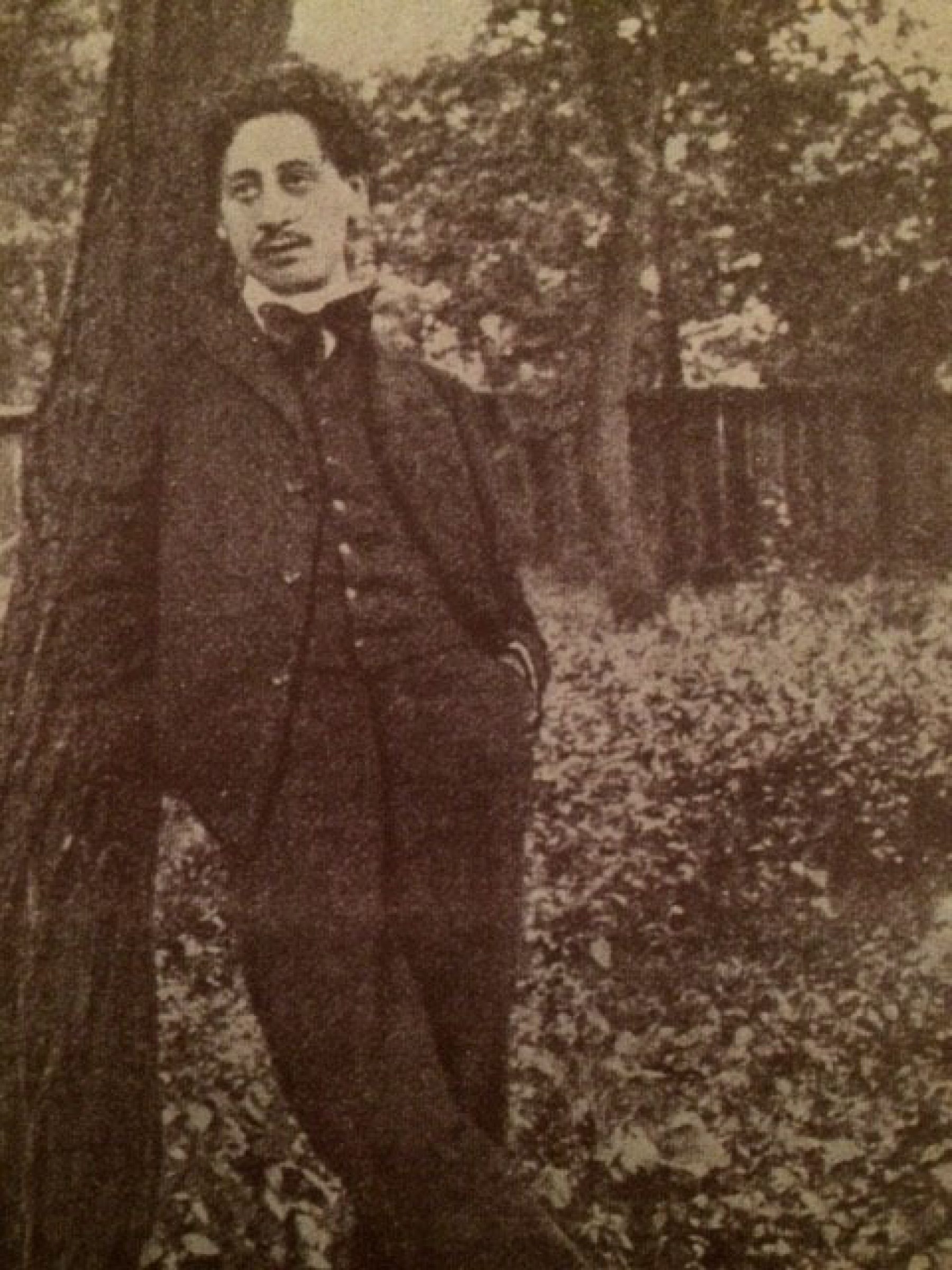

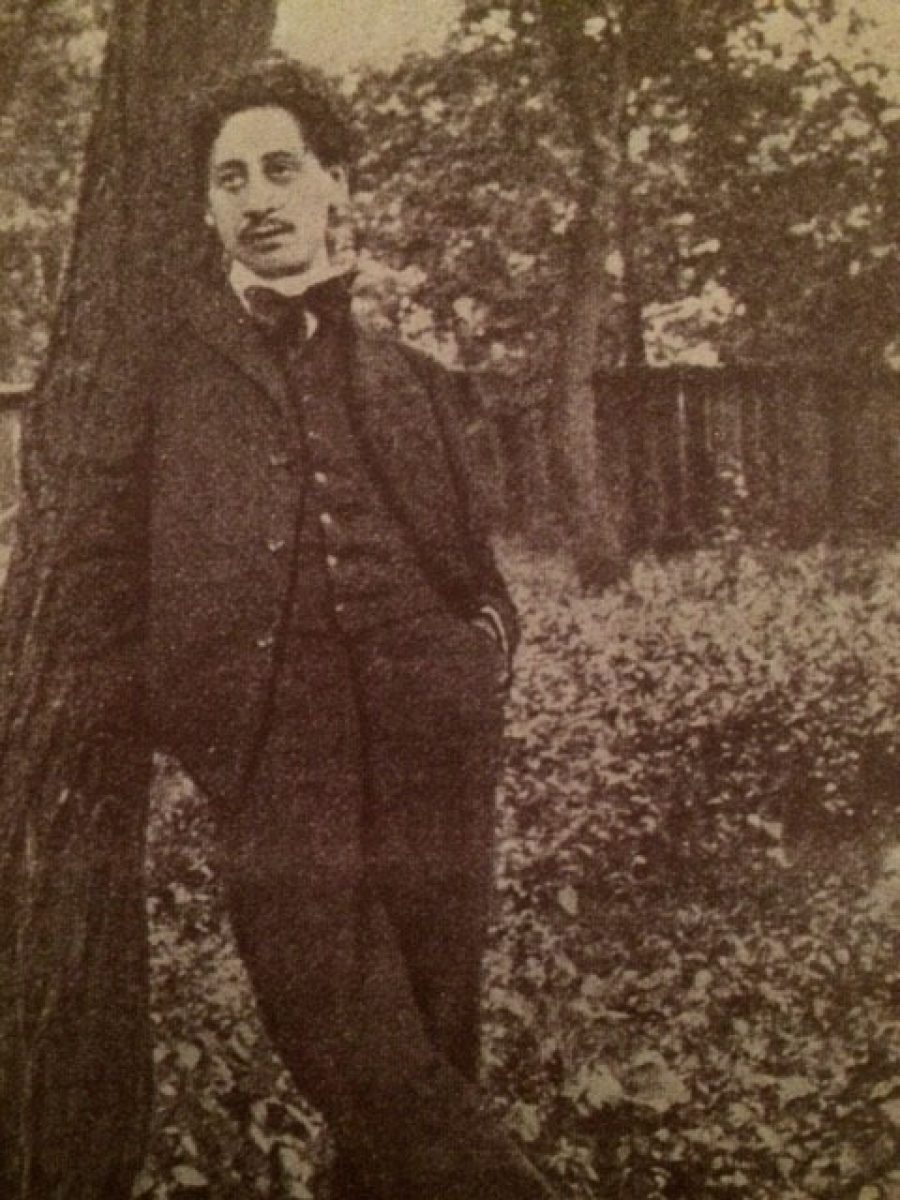

Sholem Asch, 1903

The Sholem Asch Festival: Poland Rediscovers a Yiddish Dramatist

David Mazower

Every two years around this time I visit the Polish town of Kutno, for the Jewish festival named after my great-grandfather, the Yiddish writer Sholem Asch. He was born there in 1880 in a single-story wooden house on one of the town’s main streets. Asch left Kutno as a teenager, having grown weary of his religious studies, but he returned at regular intervals to visit his mother Malka, his brother Wolf, and his father’s grave in the Jewish cemetery at the edge of town.

Today, few traces remain of Kutno’s rich Jewish past. A shopping mall has replaced the Asch house, Malka Asch’s lean-to courtyard dwelling has long gone, and the Jewish cemetery and Kutno’s Great Synagogue, both destroyed by the Nazis, are marked by austere monuments. But, like a dybbuk, Jewish Kutno persists, a ghost town for those who know. Local history enthusiasts point out its pre-war landmarks: the rabbi’s house, the former yeshiva, and the Peretz Lending Library, once full of Yiddish books. At the other end of town, opposite the Lutheran church, the apartment block built by Asch’s brother Wolf in 1912 is newly renovated, gleaming white in the autumn sunshine.

Post-communist Kutno began to remember Asch in 1993, announcing a nationwide literary competition on a Jewish theme. It’s been a feature of every subsequent festival, attracting a remarkably high standard of entries. This year 131 people from all over Poland submitted stories, poems or essays, with the first prize awarded for a short story entitled “Esterka.”

Sholem Asch, 1903

The Szalom Asz Festival is funded by the municipality and organized by a dedicated team of staff at the town’s library, which is named after the Polish novelist Stefan Żeromski. It’s grown steadily over the years and now involves schoolchildren, teachers, residents, local musicians, amateur groups, and visiting academics and performers.

On the morning of my arrival, teams of high school students were out in the streets, completing a quiz about Kutno’s Jewish heritage. Other events in this year’s festival included a Jewish song competition for students in the local theatre, talks about Asch in Kutno and Łódź, performances by local klezmer bands, and a sit-down Jewish dinner cooked and served by students from Kutno’s catering college. The Festival’s finale was a full-fledged production of Fiddler on the Roof by Warsaw’s State Jewish Theatre, playing to a capacity crowd of several hundred in the town’s renovated Culture Palace.

Kutno’s Library is also bringing out impressive new translations of Asch’s works. Two years ago, they published a handsome volume with new Polish translations of six Asch plays. For 2015, the Library commissioned a new translation of another play, Bund fun der shvakhe (Alliance of the Weak, or The Weak find Common Cause). It was translated by Dr. Magdalena Ruta and edited by Professor Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska, two of the leading contemporary Polish Yiddish scholars. (The Library hopes to publish it in a second volume of Asch’s plays in translation.)

One of the most impressive evenings of this year’s Festival featured students from Kutno’s Władysław Grabski High School no 3. They staged Asch’s one-act play Um vinter (In Winter), using the translation from the Library’s 2013 volume. The piece is more about mood and atmosphere than plot. Asch calls it a lebensbild - literally “a scene drawn from life,” a word Yiddish playwrights often use to describe a slice of city or shtetl life, and a style of writing that can feel as much like poetry as drama.

Secondary school students in Kutno’s museum learning about Judaism as part of their quiz for the Asch Festival.

The action centers on a family group: Dvoyre is a widow struggling to keep her home together and anxious to marry off her two grownup daughters, Roma and Yulka, as quickly as possible, starting–according to tradition–with the eldest.

Two teachers at the school, Dorota Chojnacka and Halina Sankowska, adapted and directed the play. It was the first time students in Kutno have performed a complete play by Asch, and I was curious to know more about the process of staging it.

“I started to think about staging the play when I realized that Asch’s plays had hardly been put on in Poland since his own lifetime,” Halina told me. “Then I read all the plays published in Kutno for the 2013 Festival. My colleague Grażyna Baranowska drew my attention to In Winter. She pointed out that it’s much shorter than the other plays and so it’s easier for inexperienced actors to learn.”

Learning about the old Jewish cemetery (on the hill).

“We used the new translation from the book, but we made some changes to make the text more comprehensible for both actors and audience; for example, we replaced some old-fashioned words with their contemporary equivalents. We also added a short passage from Asch’s novella Dos shtetl (The Little Town)–a description of a severe winter that the older sister reads when she’s standing by the window. We also used extracts from three stories from a Polish volume of Asch’s short stories. For two reasons: to make the play a little longer, and to add some more description of what life was like in poor Jewish communities at that time.”

“For all of the students, it was their first contact with Jewish literature and culture. Working on the play together, it was a chance for us to help them learn about Sholem Asch, and about the shared Jewish-Polish society in Kutno before the war. We’re already thinking about staging another Asch play for the next Festival in 2017. Or maybe dramatizing a short story, for example The Rebel, about a young bride who refuses to have her hair cut off and wear a wig on her marriage.”

In addition to all these local efforts, the Festival also included an academic symposium – a public platform for some of Poland’s leading young scholars of Yiddish literature. Lublin-based academic Monika Szabłowska-Zaremba spoke about her research on the Polish-language Jewish press. She has discovered some fascinating reports, including one in the main Polish-language Jewish daily Nasz Przegląd (Our Review) on 20 July 1927. Headlined “Warsaw thieves celebrate Sholem Asch’s fame and literary reputation,” it’s a surreal crime report with a delightful denouement:

An extraordinary theatrical type of theft was committed yesterday on the streets of Warsaw; a ‘virtuoso’ performance, you might say. Some thieves, ’artistic maestros,’ took Sholem Asch’s famous play Motke Ganev (Motke the Thief) right off the stage and into the street. They slightly deformed it, or reformed it (we’ll leave it to the critics to decide), adding two new roles: an organ-grinder and a singer. Nobody could fault the quality of the performances. They staged the play not for the gratification of the theatre audience but in the ‘exalted’ spirit of ‘art for art’s sake.’

Here’s how the performance played out: Sholem Asch’s brother, Jacob Asch, a well-known fur merchant, lives in a third floor four-room apartment at 22, Świętojerska Street. A few days ago Mr. Asch left for Krynica; his wife and children had previously gone to holiday in Urle. He took extra measures to protect the apartment with locks and padlocks and left it under the watchful eye of the janitor. Who would have thought that the janitor (even if he was unfamiliar with the play Motke Ganev) wouldn’t be able to look after the apartment?

Yesterday afternoon an organ-grinder appeared in the courtyard with a ‘singer.’ It’s a regular sight in the Jewish quarter, so nobody thought anything unusual was going on when the organ-grinder sang songs from Asch’s play Motke Ganev for over an hour. But as soon as the organ-grinder left, people started shouting “thieves have broken into Mr. Asch’s place.” The doors to the apartment were smashed and the wardrobes emptied out: the thieves even stole the carpets and took several hundred dollars in cash.

And now - the final act: on one of the tables they left a note in Yiddish with this message:

“Dear brother of Sholem Asch! We are truly sorry but as you must know we also need to make a living. Regards to our beloved Sholem Asch–expert on our fraternal soul.” And the signature on the note? Motke Ganev.

It’s a wonderful anecdote, not just because of the Warsaw thieves’ tongue-in-cheek sense of dramatic irony, but also for what it tells us about Asch’s reputation in Poland. By the late 1920s, he was approaching the height of his fame and popularity as a novelist and dramatist. Theatre hits were a key part of that, not least the long-running dramatization of his novel Motke Ganev, set in the Polish-Jewish criminal underworld.

Pre-1939 Poland was stubbornly resistant to the idea that the rich Yiddish cultural world in its midst was part and parcel of national life. There were few Polish translations of major Yiddish classics, or Polish-language productions of Yiddish plays. Decades later, the dozens of Jewish festivals in towns and cities across Poland are playing an important part in changing that.

More photographs of pre-World War II Kutno are found here.