"Dzigan and Shumacher in the Russian Forest," Adi Kaplan and Shahar Carmel, oil pastel on paper, 10cm x 10cm.

Rubber Bullets at False Targets: On Dzigan and Shumacher’s Performance in the Soviet Union

Diego Rotman

Shimen Dzigan and Isroel Schumacher’s professional artistic careers began as actors in the experimental Yiddish theatre “Ararat,” in Łódź, which was established in 1927 under the direction of the poet Moyshe Broderzon. After a few years, they left for Warsaw and founded an independent satirical theatre that would play a key role in eastern Europe’s Jewish culture. Their theatre was characterized by sharp humor, witty political satire, and extraordinary acting. During World War II, Dzigan and Shumacher continued their artistic activity in the Soviet Union, and it was there that they were arrested in 1941 and charged with anti-Soviet activities. They spent four years in a labor camp in Kazakhstan. In 1947, Dzigan and Shumacher returned to Poland, and performed there for two years, until they left for a performance tour in Europe. They first performed in Israel in 1950, and acted together until they separated in 1960. Schumacher died in 1961 and Dzigan continued to appear with his satirical theatre in Israel and abroad until 1980.

The following fragments concentrate on the key years of their artistic career–1939 to 1941–and are based on excerpts from my recently published book. On May 30, 1939, some months before the beginning of WWII, Dzigan and Shumacher staged the last performance of the Satirical Yiddish Theatre in Warsaw. In one of the skits, Shumacher spoke to the audience about Polish Jews’ hard living conditions and informed the theatregoers of the sad fact that he had to leave their homeland. He ended his speech with a farewell to all those present in the theatre, including the mosquito he caught buzzing around him:

זײַ געזונט, פֿליג! איך פֿאָר אַוועק און לאָז דיך איבער. גלייב מיר, פֿליג, איך בין דיך מקנא. דו קענסט פֿרײַ פֿליִען וווּהין דו ווילסט און ווען דו ווילסט. דו ווייסט ניט פֿון קיין עמיגראַציע־שוועריקייטן, פֿון קיין פּאַס, פֿון קיין וויזע, פֿון קיין אַפידייוויט. גלייב מיר, פֿליג, איך בין שוואַכער… פֿון דיר

“Goodbye, mosquito! I leave [the country] and leave you here. Believe me, mosquito, I am jealous of you. You can fly freely wherever and whenever you want: you don’t know about emigration difficulties, about passports, about visas, about any affidavits. Believe me, mosquito, I am weaker…than you.”

Then Shumacher appeared onstage again with Dzigan. This time, they were disguised as bears, because, as they explained, if the Jews in Poland could not live there any longer as human beings, they should wear animal skins. Maybe this would allow them to save their lives. This identity change, which required that Polish Jews leave all cultured, human existence for a life in the wild, was presented as the last option open to Jews in Poland of 1939.

Dzigan and Shumacher’s last prewar performance took place in Kraków on August 23, 1939. The artists remained in Poland until the following month, when they learned that their names were on the Gestapo’s blacklist. They left for Białystok in September 1939, ending what Dzigan called, in his autobiography, the happiest period in his life.

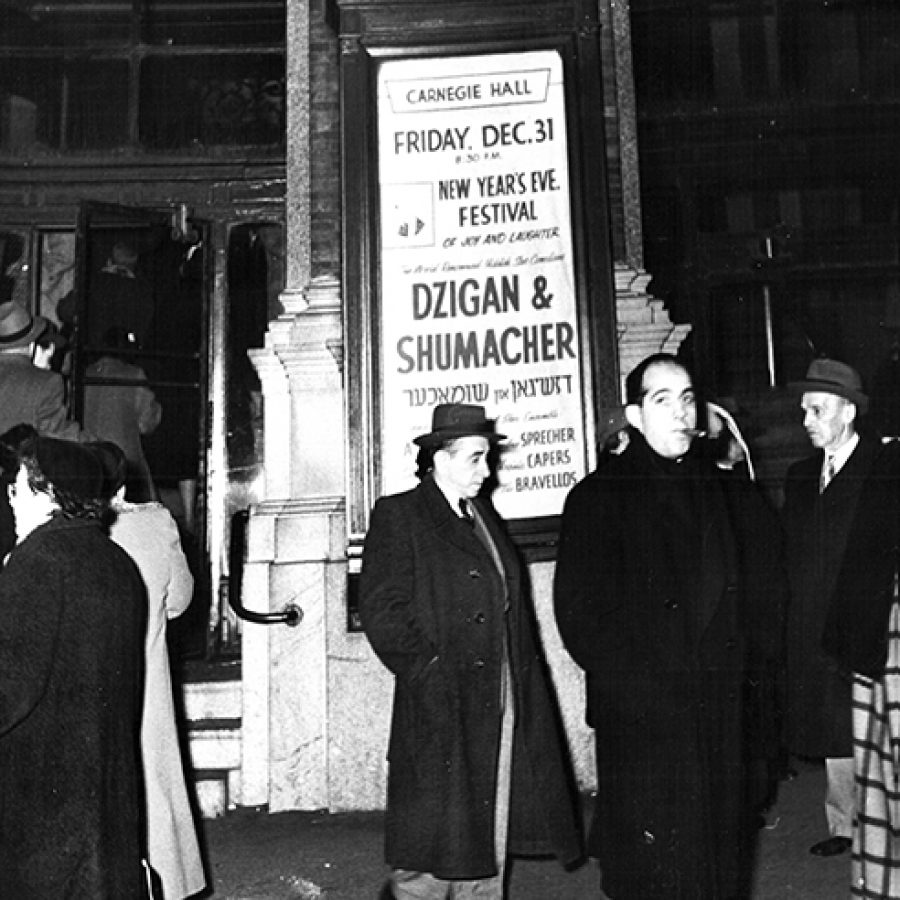

Billboard for Dzigan and Shumacher’s performance at Carnegie Hall, December 31, 1954. From the Lydia Shumacher-Ophir Collection, printed in The Stage as a Temporary Home.

Dzigan and Shumacher’s sojourn in the Soviet Union began in February 1940 and lasted seven years. In his autobiography, Dzigan dedicates considerable space to this period–more than forty percent of the book–evidencing the strong influence that this period had on his and Shumacher's lives and work. The autobiography includes reviews from the Soviet press, interviews with the artists, witticisms,and skits devoted to life in the Soviet Union. These materials allow us to form a vivid picture of this vital period of the duo's development.

In February 1940, five months after their arrival, Dzigan and Shumacher were appointed artistic directors of Der bialystoker minyatur teater (The Białystok Miniature Theatre), which was supported by Minsk’s department of culture. Broderzon, Moyshe Nudelman, and Y.S. Goldstein wrote most of the scripts. Shaul Berezowsky served as the composer and orchestra conductor. Adam Umansky, a member of the Communist Party, was the administrative and general director. All the actors, as well as seven of the eight musicians who played for the theatre, were Jewish refugees from Poland. Only one musician was — “mysteriously” — a non-Jew from Białystok.

Until its dissolution in 1941, Der bialystoker minyatur teater performed the revues Zingendik un tantsndik (Singing and Dancing) and Rozhinkes mit mandlen (Raisins and Almonds) as part of a tour that included stops in Moscow, Leningrad, Lwów, Odessa, Kiev, Khar’kov, Minsk, Bobruisk, Nikolaev, Baku, Yerevan, and Tbilisi. The Taganrog Aviation College also hosted them, and they also performed special shows for Russian army squads. The troupe enjoyed great success. In Moscow, for example, they gave eight standing-room-only performances at the Hermitage Theatre Hall. In Nikolaev, leading cultural and civic figures welcomed the troupe upon their arrival at the train station.

Dzigan and Shumacher in Di Velt Shoklt Zich,” 1953. From the Lydia Shumacher-Ophir Collection, printed in The Stage as a Temporary Home.

The rhetoric used in the meetings that troupe members had with government officials, as well as in reviews in the press, presented Dzigan and Shumacher’s theatre as a symbol of the Red Army victory over the Polish enemy and bourgeois society. The name Białystok, used as part of the theatre company’s official name, was a reference not to the theatre troupe’s origins, but was a clear symbol of the fact that this was a theatre from an annexed city, a theatre of refugees, a theatre of “liberated Polish Jews.”

“Dzigan and Shumacher planning a new program,” 1950s, Israel. From the Lydia Shumacher-Ophir Collection, printed in The Stage as a Temporary Home.

These Soviet institutions demanded that troupe members make changes to their programs’ content and to the physical appearances of the actors and characters, and to reshape their cultural identity. In every city where the theatre performed, it had to get approval from the local censorship committee. As a result, the repertoire changed, presenting only neutral content, primarily skits based on popular Russian and Jewish songs. In these new political circumstances, satire could no longer refer to local political, economic, and social realities. Instead of creating political satire aimed at the objects of their choosing, all their talent had to be redirected to show that those responsible for all the trouble of the Soviets were the surrounding countries. Dzigan and Shumacher could only be critical of the English, the French, the Americans, and themselves: Jewish refugees “liberated” from “capitalist Poland.” The humorist working in such a political system, concluded Dzigan, had no alternative other than to “shoot rubber bullets at false targets.”

***

This article is an excerpt from my book The Stage as a Temporary Home - On Dzigan and Shumacher’s Theater (1927-1980) [Hebrew], published by Magnes University Press in 2017.