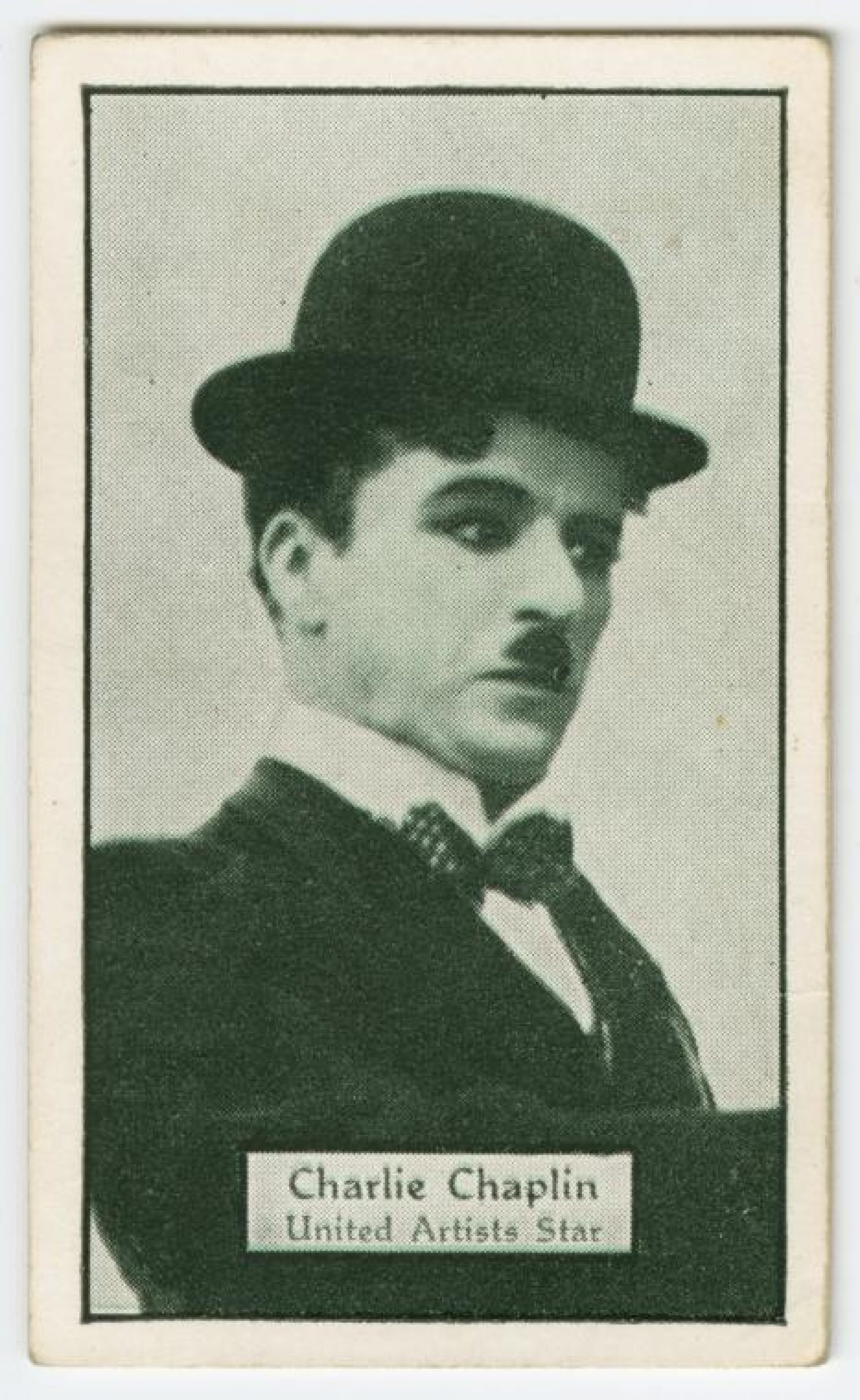

"Charlie Chaplin, United Artists star, "George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Dystopia on the Verge: Or Why a 1934 Yiddish Play About Charlie Chaplin Still Matters

Debra Caplan

The Setting:

An obscure port city, somewhere in Europe. In the foreground stands a familiar figure with an iconic mustache and dark hair, surrounded by ambassadors from every country in the world. Famous Jews, carrying their passports, line up under the watchful eyes of police guards.

The order is made: every Jew in the world is to be expelled to British Mandate Palestine, which has been jointly purchased by the global ambassadors so every country in the world can rid themselves of Jews forever. No country will engage with the Jewish land, Hitler promises. There will be no embassies, no trade partnerships, just isolation. “Us without them. Them without us,” agree the ambassadors. One by one, Hitler deports the most famous Jews in the world, including:

- Albert Einstein (“The most dangerous of all! The brainiest of their brains!” thunders Hitler)

- Baron Rothschild (“You forgot to rob me first,” he reminds the ambassadors)

- Max Reinhardt (“Your spectacle is nonsense. I’m telling you as a director,” says Reinhardt.” “Who’s directing now?” sneers Hitler)

We’re also introduced to other famous captives, among them the activist Vladimir Jabotinsky, the well-known Forverts newspaper editor Abe Cahan, the Yiddish writer Sholem Asch, Stephen Wise, the president of the American Jewish Congress, and Nobel Prize-winning scientist Otto Warburg. All are promptly deported to the ship, along with a beautiful Hollywood actress named Alexandra who weeps for her Gentile lover, a famous boxer with perfect teeth.

One of the last captives to be deported is Charlie Chaplin, wearing his signature hat and cane. “I’m not a Jew! I am a pure Gentile youth!” Chaplin protests, to no avail. Hitler and his racial scientists have already decided his fate. Chaplin’s father was a rabbi named Kaplan who changed his name, Hitler explains to the crowd. And besides, his (falsified) birth certificate proves it.

CHAPLIN. Why would you falsify my birth certificate?

HITLER. Our racial scientists have conducted their research. We know the truth.

CHAPLIN. I am not circumcised.

HITLER. Our racial scientists have determined that you are.

CHAPLIN. But I’m not.

HITLER. How can you know if you’re circumcised or not? Our racial scientists know.

Flustered, Chaplin decides to go with Einstein and the others and make a film about the experience. “Goodbye, Mr. Cohen!” he shouts to Hitler as he departs. “Pig shit!” Hitler replies. “Is my name Cohen?” “Is my name Kaplan?” Charlie retorts.

As the ship sails away, the British Ambassador approaches Hitler with a message from the King. His Majesty’s government, he announces, will be keeping just one Jew—“for important government purposes”—the chemist Chaim Weizmann. Weizmann—later the first President of Israel—was best known in the 1930s as a brilliant laboratory chemist. His 1915 invention of a new process for producing acetone, a key component in the production of smokeless gunpowder, helped the Allied Powers win World War I.

Hitler is aghast, but the British Ambassador insists that the matter has already been decided. Besides, he adds, “England cannot make do without at least one Jew.” So Chaim Weizmann becomes the only Jew in a non-Jewish world, and Charlie Chaplin becomes the only non-Jew in an isolated Jewish country established by Hitler.

And…scene.

Aaron Zeitlin.

So begins Di yidishe melukhe, oder, vaytsman der tsveyter (The Jewish Kingdom, or, Weizmann the Second) a dystopian comedy published by the Yiddish writer Aaron Zeitlin in Warsaw in the spring of 1934. Zeitlin wrote the play in response to the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party in Germany. Di yidishe melukhe is a blistering comedy about finding laughter in the absurdities of an uncertain, tumultuous historical moment—a moment in which institutions and systems that have lasted for centuries are breaking down, a moment in which hate and bigotry render people unable (or unwilling) to perceive distinctions between rumor and reality, a moment in which the truth matters less than what people believe it to be. In short, it’s a dark comedy about a moment of uncertainty not entirely unlike our own.

What is the truth, who controls it, and to what ends? Zeitlin asks. Indeed, there were persistent rumors throughout Charlie Chaplin’s lifetime that he was secretly Jewish. After all, it was common practice for Jews in show business to change their names in order to succeed. Albert Einstein was convinced—and he wasn’t alone. In the 1948 edition of a Jewish encyclopedia, Chaplin was described as a Jewish movie star whose given name was Israel Thornstein. That same year, the US Navy investigated whether Chaplin was illegally shipping guns and tanks to Palestine (he wasn’t). Chaplin was also the subject of a massive 1900-page FBI investigation under J. Edgar Hoover, and his file described the actor as “of Jewish extraction.” In Britain, the MI5 also spent years investigating whether Chaplin was secretly a Jewish Communist born in France as Israel Thornstein. The rumors continued to swirl even after Chaplin’s death. Soon after he was buried in Switzerland, Charlie Chaplin’s body was stolen from his tomb (it was later found and recovered). Media reports suggested that local antisemites had dug up Chaplin’s body because he was a Jew buried in a Gentile cemetery.

Even Chaplin himself seems to have sometimes wondered if the rumors were true. When the famous cantor Yossele Rosenblatt visited him, Chaplin told the cantor that he owned all of his records that and he loved them because ‘they unite me, oh so closely, with my Jewish ancestors.’”

In the play, fiction becomes fact in the hands of a political villain whose every word is repeated by the world ambassadors who fawn over him. Chaplin has his birth certificate and other documents to prove that he’s a British citizen and not Jewish, and as he tells Hitler, he can prove that he isn’t circumcised – but in this dystopia, facts and evidence have ceased to matter. The truth is whatever Hitler says is the truth. And so, Chaplin is deported along with the entire global Jewish population.

Once the ship arrives, the Jews appoint Albert Einstein to be their first President. But running a country isn’t as simple as anyone thought. Nobody can agree on what the country ought to prioritize, and the Jewish country’s initially idealistic democracy soon devolves into polarized chaos. The Return Party wants to convince the world to take the Jews back. The Jerusalem Party believes that staying put is the only way to survive. The hedonists favor throwing carnivals and raucous parties. In the middle is Einstein, who never really wanted to be President in the first place and would much rather spend his time in his observatory studying physics and astronomy. Parliamentary discussions become shouting matches, and the country soon devolves into a series of coups and revolutions. Charlie Chaplin is there to film it all. “What a film it’ll make!” he tells Einstein. “The best Chaplin movie yet!”

Meanwhile, in the outside world, a lonely Chaim Weizmann is the only person celebrating Hanukkah in all of London. There’s been a disastrous world war, followed by famines, economic depressions, and crises without end in every country in the world. The British government comes to Weizmann and asks him to invent something to solve the problems of the world.

WEIZMANN. I’ve got it! It’s a simple solution, and it will save all of the governments.

CHANCELLOR. All of them?

WEIZMANN. All of them! My Lord, people will always be unsatisfied. Always! They’ll be upset about whatever you’re not giving them. You get them food? Good. And then what? You don’t understand people, my friend. Do you know what the solution is? No, you don’t. The solution is having someone to blame. Having someone to blame for everything—that is the secret of successful leadership.

CHANCELLOR. What do you mean, sir?

WEIZMANN. All leaders need one thing: someone to blame. That’s everything. There’s nothing that people need more than a reliable scapegoat. You’re starving, you’re dying, you’re hungry, thirsty, sick, unemployed? On the contrary: it’s his fault, it’s her fault! Your wife hits you? Your friend stole from you? Your child died? On the contrary: it’s his fault, it’s her fault!

CHANCELLOR. (Impatiently) That’s all very well, but… be concrete!

WEIZMANN. Concrete? Aren’t the Jews the best and most reliable scapegoats? Let the Jews back in! Beg them to return. Open all the gates for them, everything will be restored to how it was, and everybody will be happy. They want to come back, I’ve heard…My Lord, Great Britain should take on this initiative.

(Pointing to the Hanukkah candles)

And me…I won’t be so lonely anymore. I won’t be so alone. The only Jew in the world who lights Hanukkah candles. There, that’s my remedy for all of your plagues: make it so that in London and every city in the whole world people will light Hanukkah candles, eat latkes, and play card games on Christmas again.

The leaders of the world are convinced—even the Germans—and a delegation of ambassadors sail for the Jewish land to beg the Jews to return so that they’ll have a scapegoat for their own leadership failures. Without someone to blame, Zeitlin suggests, those in power simply can’t retain it. “You Jews will serve us, make inventions and discoveries, supply us with other Einsteins, build and develop our cities, our languages, our tastes, everything,” promises the German chancellor, “and we will blame you—because we need scapegoats.”

Some Jews return, while others stay in Jerusalem to awaken the Shulamite from the Song of Songs—who has been sleeping since Biblical times, awaiting their return—and the play ends.

“Jewish-Palestine Participation - Grover Whalen and Chaim Weizmann with model,” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Reading and translating this play in 2019, I was struck again and again by the unintentional poignancy of Zeitlin’s comedic vision. Watching Hitler’s rise from his home in Warsaw in 1934, Zeitlin imagined what must have seemed at the time to be an absurd, exaggerated dystopia. A world in which Hitler and his vision of a world without Jews had conquered dozens of countries. A world in which Jews were deported en masse. A world in which no one stepped in to help. A world in which Hitler enacted drastic measures to rid the world of its Jews.

Zeitlin’s darkest imaginings didn’t even come close to the true horrors that awaited. The play remains a comedy, but it’s one that a contemporary reader cannot help but layer with our own knowledge of what actually came next.

Five years after writing Di yidishe melukhe, theatre would save Zeitlin from a fate far worse than the dystopia he had imagined. In 1939, just before Germany invaded Poland, the American Yiddish theatre director and impresario Maurice Schwartz invited Zeitlin to New York to work on a production of his play Esterke. When the war broke out, Zeitlin could not get back to Poland. His wife, two children, and parents died in the Holocaust. He spent the next several decades haunted by guilt.

When Di yidishe melukhe was re-published in Zeitlin’s collected dramatic works, Zeitlin edited out Hitler’s name entirely, replacing him with a mustached doppelgänger called simply “The Aryan,” and imagined him being replaced after the war with a new German leader who, at least outwardly, rejected Hitler’s ideology. Perhaps reading the play as it was originally written was too painful for him, knowing as he did what happened next.

What can we learn from dystopian writing of the past when their all-too-real futures have already come and gone? Zeitlin’s play asks us as contemporary readers to imagine what it might have been like to be a Jew watching world events unfold in 1934, to imagine the future from the perspective of that present, to find humor and levity in a situation that is anything but humorous. In this way, it offers us a perspective that’s hard to find—but crucial for understanding what it was like to live through this moment.