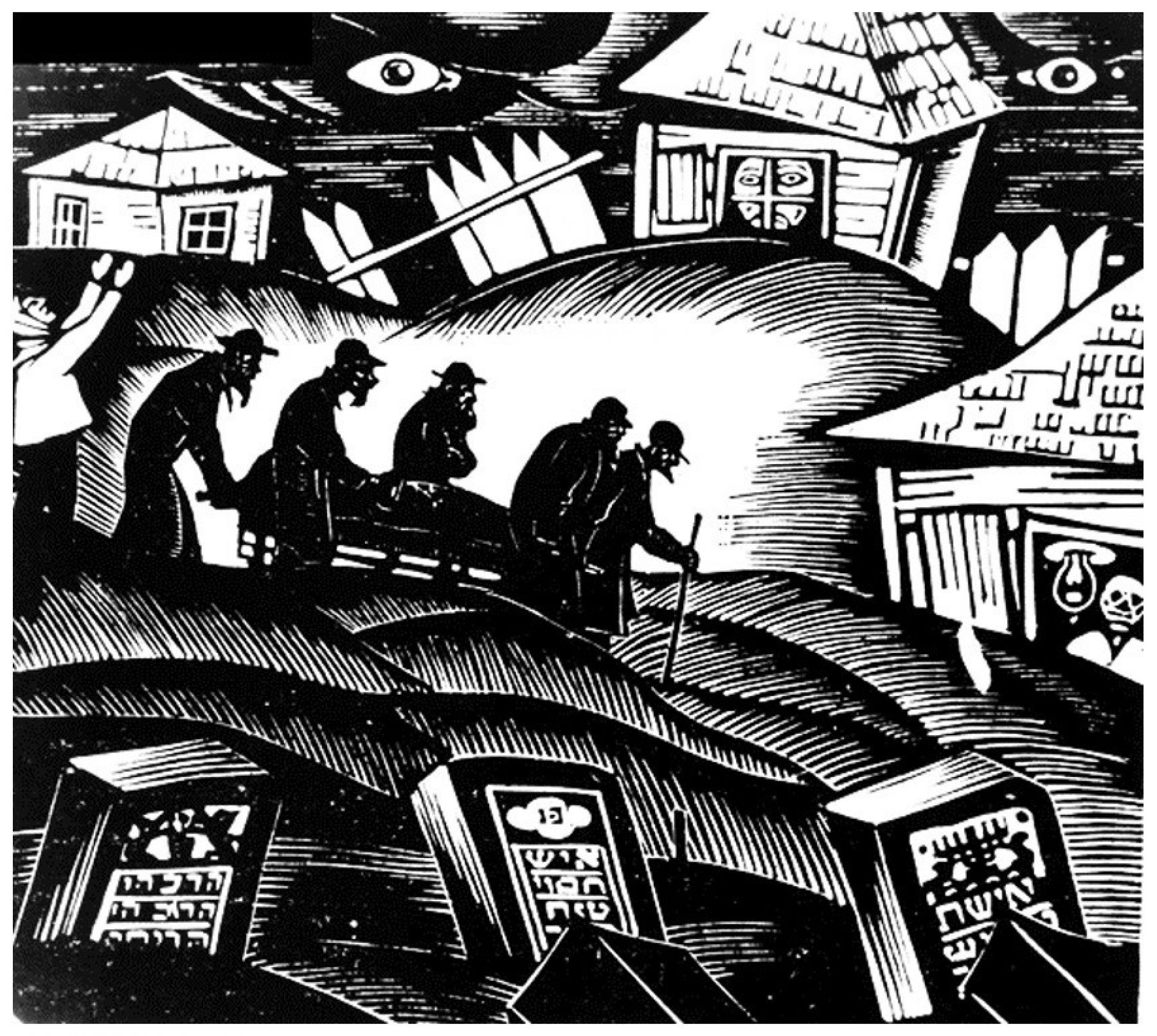

Image: Shlomo Yudovin, "A Jewish funeral in Vitebsk." Woodcut used in scene transition.

The Dybbuk of COVID

Faith Jones

The Congress for Jewish Culture’s YouTube Live performance of Der dibek (The Dybbuk), presented in Yiddish, premiered on December 14, 2020, in honor of the play’s 100th anniversary. In a shortened adaptation that ran seventy-five minutes, it was as spooky and moving as you could wish for. This was not just because it is a play about death and loss, and we are in a moment of death and loss. And it was not just because the actors were uniformly excellent, led by the extraordinary Yelena Shmulenson. It was also a feat of staging and design, utilizing the strengths of online performance and side-stepping many of its problems.

If you don’t know S. An-Ski’s The Dybbuk, or, Between Two Worlds, now is a good time to go read this excellent summary and catch up. One of the central pieces of the Yiddish theatrical repertoire, it is primarily concerned with questions of tradition and modernity and the debt of the living to the dead. Along the way it somehow (without An-Ski exactly intending it) also confronts questions of gender and sexuality in traditional Jewish life.

We have been looking at Yiddish theatre in the age of COVID, in the hopes that something good could come out of the loss of live theatre. New techniques, new audiences, new approaches: anything that will make Yiddish theatre come back stronger. I spoke to director/adapter Allen Lewis Rickman and producer Shane Baker about how their Dybbuk production came to be and what lessons we might learn from it. Shmulenson stopped by our Zoom call for a few moments and was able to add a performer’s perspective on inhabiting a physically demanding role within the confines of what was essentially a permanent close-up.

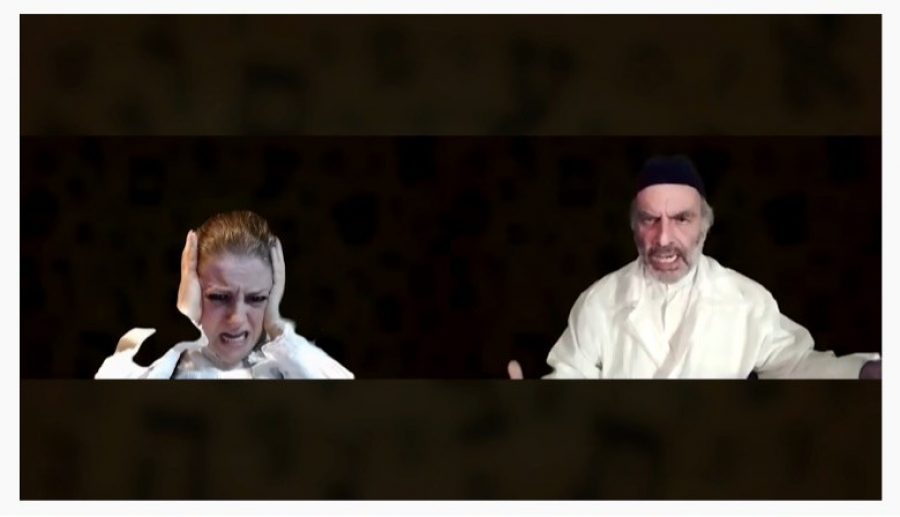

Image: Yelena Shmulenson as Leah and Mendy Cahan as Reb Azriel Miropolyer in a still from the Congress for Jewish Culture’s Der dibek, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sop8T-OxN2M.

This production was, like many similar undertakings throughout December and January, timed for the 100th anniversary of the first production, the famous Vilna Troupe performance that ran as a memorial just after An-Ski’s death. Baker had been considering it for some time, knowing he wanted to not only mark that anniversary but also to pay tribute to his friend, the late actress Luba Kadison, who was long associated with the play. His initial idea was a simple reading, but after he asked Rickman to direct, the project mushroomed. They had been given an adaptation from the repertoire of Dina Halpern, but they saw that it missed several dramatic points they were keen to retain. The two worked closely together on casting and interpretation but Baker gave Rickman leeway to create a production design and to write a new adaptation. As the production grew in complexity, it seemed they would have to cut something back until an anonymous donor came forward with a grant to honor the memory of Chana Yachness, a long-time supporter of the Congress and other Yiddish cultural organizations. With this, combined with the COVID-era reality that many actors were out of work and available at the Congress’s pay scale, they were able to afford a fuller production than they had originally envisioned. Another benefit of online theatre: the actors could be anywhere in the world, as long they had a computer, webcam, and wifi. They hailed from four countries spanning ten time zones. “To produce this live with this same cast would be a couple hundred grand,” Baker says.

Rickman has a film background, which also assisted in the transition to online theatre. Baker had suggested using woodcuts as a thematic element in the production design, which Rickman incorporated in a number of ways. By using different sequences of woodcuts for each scene transition, but always ending with one image of falling Yiddish letters, a visual unity was achieved. The alphabet woodcut was also used (darkened and in soft-focus) as the background for many scenes. The alphabet served as a metaphor for the kabalistic elements of the play.

Although they had at first assumed they would do a live performance, the limitations were too severe. A moment’s wifi lag in any of the ten performer’s homes, an unexpected dog barking or doorbell, could interrupt the dramatic momentum of the play. Pre-recording also allowed for simple editing—Rickman points out that he was not willing to use camera tricks to achieve a creepy or supernatural feeling, instead using traditional theatrical techniques of music, production design, and of course, acting, to achieve the mood they were looking for. Their video editor, Uri Schreter, is a Yiddish speaker, which greatly enhanced his ability to meaningfully interpret Rickman’s shot design. At times, he had to suggest alternatives. “We’re dealing with the technical skills of ten different people, and the equipment of ten different people. That means inevitably, there are some shots we couldn’t do because we didn’t have good enough footage for person X,” Rickman says. At one point a wifi flicker was allowed to stay in frame however: Shmulenson’s Leah begins to break up at a moment of peak dybbuk-possession. Rickman saw no need to alter this accidental effect.

The shooting schedule involved scene rehearsals with individual people or pairs, followed by a full-cast read-through. Then a week of further small group rehearsals were held to further hone the material, and then a full day of shooting with the full cast. During the following week a few more re-takes were shot. This was important to Rickman to retain the feel of people interacting in a space.

Image: Yelena Shmulenson and Mendy Cahan in foreground, with (left to right in background) Michael Wex, Suzanne Toren, Amitai Kedar, Mike Burstyn and Shane Baker, in a still from the Congress for Jewish Culture’s Der dibek, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sop8T-OxN2M.

One important factor in the success of this production is the unity Rickman, Baker, and Shmulenson all express over their interpretation of Leah as an active participant in her own haunting. Although Shmulenson hasn’t seen the movie—she did not want to be influenced by it—Rickman and Baker both reject the film’s suppression of Leah’s agency. (They have other criticisms of the film as well, including its addition of a half-hour prequel that’s essentially a spoiler). Shmulenson regrets the inability to use a full range of acting techniques: “It was incredibly limited in the physicality as opposed to what you could do in live theatre,” she says. The virtual background was another limiting factor, because large arm motions could cause a hand to disappear. As a result, she put much of the action into her voice and face, which was a strain both physically and mentally. Some of the re-takes had to wait a few days for her to recover. Baker feels her use of smaller movements ended up almost being like a dance interpretation. Compared to the movie’s portrait of a possessed Leah, “this was so much more violent,” he says.

Shmulenson also feels a return to the text gave the character a depth that can easily be overlooked if you approach the play within a traditional horror trope. “I usually spend more time charting the progression of the character, but this one, everything was there in the text. She wants this, she actively initiates it. As opposed to pretty girl, long dress, something happens.”

Baker also wonders what an ahistorical reading of the play has done to limit Yiddish theatre. By seeing it as a folksy drama or a sentimental vision of the past (it is often called the Jewish “Romeo and Juliet”), rather than a work of art that allows the folkloric base material to retain its grittiness, the play can create the illusion of a simple bygone era. Baker proposes the solution to this is staging a complex reading, one which allows An-Ski’s questions to emerge without imposing simplistic answers on them. Although I have known and studied this play for years, the questions that occurred to me in watching this production all came from my experience of the funerals and shivas that didn’t happen over the last fourteen months. Questions like: When we are not able to mourn our losses properly, how can we ever stop being haunted by them? Is being haunted what the living will now always owe the COVID dead? Will we ever stop longing for the things that have been denied to us? How will we reconcile the “two worlds” of pre- and post-COVID?

The most stunning moment for me came as the dybbuk, speaking through Leah, refuses to leave her body, declaring, “ikh hob nisht vuhin tsu geyn”—I have nowhere else to go. At that moment in the script, the dybbuk of An-Ski’s day must have read as the Jew, with nowhere else to go, possessing the body of Europe. But now—where can any of us go to escape the death that is all around us?

Cast

The Messenger: Refoyel Goldwasser

Batlen 1/Dayan: Michael Wex

Batlen 2/Reb Shimshon: Shane Baker

Khonen: Daniel Kahn

Henekh/Mikhoel: Amitai Kedar

Batlen 3/Reb Azriel Miropolyer: Mendy Cahan

Frade: Suzanne Toren

Leah: Yelena Shmulenson

Reb Sender Brinitser: Mike Burstyn

Narrator: Allen Lewis Rickman

Credits

Adapted and directed by Allen Lewis Rickman

English subtitles by Shane Baker

Produced by Shane Baker for the Congress for Jewish Culture

Video editing and technical consulting by Uri Schreter

Music arranged and performed by Michael Winograd, based on traditional themes

Graphic design by Kenny Funk, Coffee Cup Studios

Thanks to Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel of NYPL for research assistance.