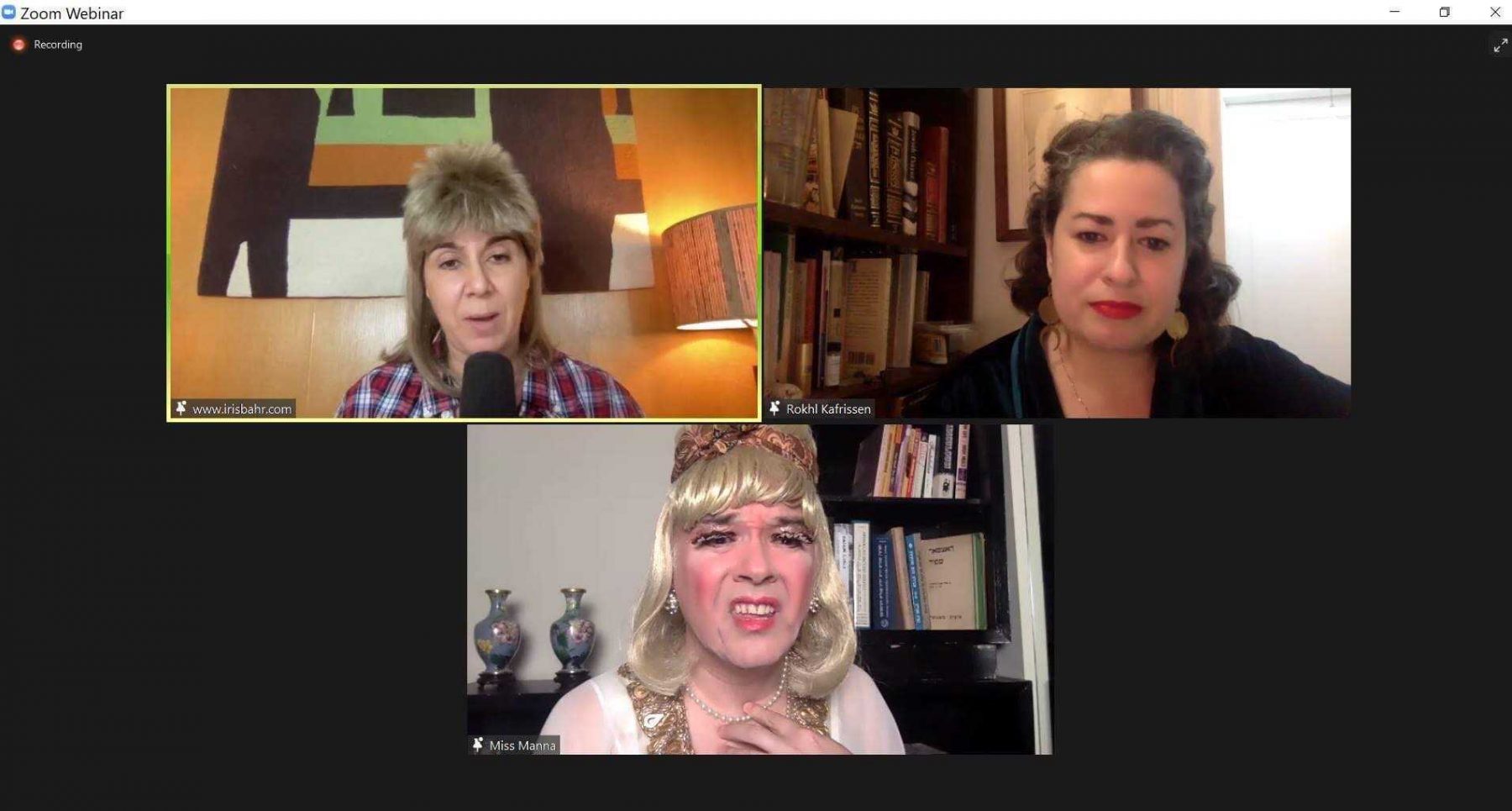

Rae Lynn Caspar White (Iris Bahr), Rokhl Kafrissen, and Miss Mitzi Manna (Shane Baker)

Shtetl Gothic on the Virtual Stage: Rokhl Kafrissen’s Shtumer shabes at the Chutzpah Festival

Sonia Gollance

What would it take for a Yiddish theatre production to rival the fame of Sh. An-ski’s The Dybbuk? What sort of topic would capture the interest of Jewish cosmopolitans in 1930s Warsaw? And what if this production gave audiences a supernatural thrill without demanding the passivity of a woman, the spiritual possession of her body?

These questions are at the heart of Rokhl Kafrissen’s wonderful Shtumer shabes (Silent Sabbath), five scenes of which were showcased in an online work-in-progress reading at Vancouver’s Chutzpah Festival on November 22, 2020 (the play itself was incubated in the LABA Fellowship Program at the 14th Street Y). Kafrissen is not the first person to have asked such questions; a fictional female-authored competitor to The Dybbuk features prominently in Rebecca Goldstein’s 1995 novel Mazel, although Kafrissen takes her narrative in a different, arguably richer direction that engages deeply with Yiddish theatre, academic Yiddish Studies, and the place of Yiddish at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

The fictional play that gives Shtumer Shabes its title is described as “Chicago crossed with God of Vengeance” but with “a dash of Dybbuk.” This “lost” play furthermore inspired an opening night riot in 1938 akin to The Rite of Spring–which shut down the theatre for a week, after which it was never performed again. As anyone who has followed Kafrissen’s astute reporting on contemporary Yiddish culture might expect, this is not a simple work. Characters unabashedly refer to Yiddish plays, cultural figures, and institutions that would be familiar to two farbrente [fervent] graduate students in Yiddish Studies who are trying to unravel a mystery (for instance, one character decides to do some reconnaissance work before meeting with a Yiddish theatre actress, so he contacts a friend at the YIVO Sound Archive to find out what recordings they have by her). Kafrissen trusts that audiences will have enough contextual clues to follow along. For audience members in the know (like many of the people in attendance at this online reading), it is a pleasure to see this world depicted on “stage.” Indeed, Kafrissen cleverly creates a parallel Yiddish theatre universe to accompany her fictional play and her fictional grande dame—such as by referencing Khatzkl Zylberboym’s theatre lexicon (presumably based on Zalmen Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater), an encyclopedic Yiddish theatre resource that gets dinged by characters both because the fictional author accepted funding from the German government in the aftermath of World War II and because, in the volume that is mentioned in the play, only five women were included. 1

Jess Berman (Liba Vaynberg) and Sonja Szajnfeld (Shane Baker/Miss Mitzi Manna)

Shane Baker–or, to be more precise, his drag alter-ego Miss Mitzi Manna–gave a masterful performance as Sonja Szajnfeld, a nonagenarian character inspired by the actresses (such as Mina Bern) who mentored Baker. Szajnfeld was a star of the Warsaw Yiddish stage, in Max Vaynberg’s celebrated Varshever Technium drama school company. When we meet her, around 2000, Sonja has just abandoned her library of rare Yiddish theatre books on a Lower East Side sidewalk. These books are discovered by Jess Berman (Liba Vaynberg) and Gareth Jones (Max Roll), graduate students who are passionate about all things Yiddish–and whose excitement for the topic is infectious. Jess gave up her dream of a stage career for academia and is now writing a thesis on Yiddish theatre with questionable success. She jumps at the opportunity to meet with Sonja and quickly realizes that the diva’s involvement in the scandalous production of Shtumer shabes offers a unique link to a long-lost play–and revelations that have the potential to dramatically alter Yiddish theatre history. Yet will Jess be able to convince Sonja to become her ethnographic informant?

Kafrissen’s play is full of the kind of “thick” Jewish cultural literacy that she regularly champions in her other work. Refreshingly, she accepts Yiddish culture as a given–it is presented as fascinating and not pathologized. In Shtumer shabes, audiences can experience the pleasure of a work where characters embrace Yiddish theatre whole-heartedly. They take it for granted that God of Vengeance can be used as a cultural benchmark or The Dybbuk as a token of the popularity of a play, although they explain these references. It is also rare to see a production that so accurately captures the highs and lows of graduate student research–the joys of discovery, the comradery of an enthusiastic but highly specialized community, the uncertainty, the dependence on an advisor’s approval. Yet other aspects of Shtumer shabes feel more universal, such as the speculation on the figure of the widow across various cultures–and why she is such a threat to the patriarchal order. It is precisely because Kafrissen has so carefully conveyed these more specific worlds that she can powerfully and convincingly meld the universal and the particular in the speech where Jess enthusiastically explains (sounding very much like the young academic she is) the significance of widows for an iconoclastic Yiddish play.

In Shtumer shabes, Kafrissen dives into questions of gender and representation that are increasingly acknowledged in Yiddish theatre scholarship. Her fictional play Shtumer shabes is described in one contemporary newspaper review as “setting off a bomb in the name of froyenrekht [women’s rights].” Sonja describes how women in the Warsaw Yiddish theatre struggled to be seen as artists when their male colleagues considered them “lambs” and “food.” Sonja made the pragmatic decision to marry a man who viewed her as both “a lamb and an artist.” Echoing Miriam Karpilove’s (1888–1955) concerns in her “Theatre: A Sketch” about the sexist stereotypes that limited women playwrights, Sonja contrasts the 1930s avant-garde theatre milieu with the opportunities she perceives Jess as having: “In our theater, none of the directors would accept a script by a woman. […] Even a story about women had to be told by a man. You have the freedom to tell any story you want, without hiding.” While the scenes selected for this reading do not yet answer the question of Jess’s storytelling, it is clear Kafrissen is able to tell a story that integrates her interest in contemporary Yiddishism with Yiddish theatre, gender politics, and a delightful touch of gothic.

Producing a virtual performance can be challenging, and it is worth acknowledging that even this relatively informal reading required prior staging and recording in a way that would not have been part of an in-person event. The scenes were filmed using Chutzpah Festival live stream director Flick Harrison’s Zoom Pro account a few days before the online event (with Kafrissen “doing double duty as director” as she explained to me), and then shared with audiences as a Zoom Webinar along with a live Q&A. Kafrissen also noted that the recording of her play for the 14th Street Y in April used Stage 10, a platform which “tries to mimic a tv broadcast more” but Harrison chose to record the Chutzpah Festival reading on Zoom for ease of integration. Information about the performance (such as the names of actors and characters) was briefly displayed in a slide show at the beginning of the event–this choice helped with the flow of the reading, but it meant that audience members could not refer to this information as easily as with a playbill, and those who joined late or could not read quickly enough missed out on some information entirely. The actors used props effectively, even “passing” papers between their separate windows. They held up signs or changed the names on their darkened screens to show stage directions, which worked seamlessly. Scenes were announced by white text on an otherwise black background that took up the entire screen. The backgrounds of the actors’ individual windows were not as coordinated, yet there is something to be said for maintaining some sense of distinction between an informal reading and a more polished production, even in the age of virtual events. More importantly, the acting itself was strong, and Miss Manna’s facial expressions were particularly effective for bringing Sonja’s character to life.

Many of the best virtual events involve conversation between interlocutors, and this reading of Shtumer shabes also included a post-show discussion with Kafrissen and Miss Manna, conducted by host Iris Bahr in character as Rae Lynn Caspar White, “a southern intellectual and professional baby surrogate” who is “full of Southern Charm and contradictions.” The choice to use a working-class, philosemitic persona was engaging, frequently hilarious, and helped remind audiences of what a play about Yiddish theatre history could offer a broader audience. Such decisions should not be dismissed in a virtual format, where maintaining audience attention is key. White and Miss Manna’s interactions were especially entertaining, such as when White compared Miss Manna’s use of the word “darling” to how Southerners “pepper really kind of biting comments with darlin’ or hon at the end.” At the same time, White’s more over-the-top qualities at times risked distracting audiences from the play itself, and made it harder for the moderator to engage in more sophisticated analysis with Kafrissen and Miss Manna. In one notable instance, White used the Jewish term “tsnieus” (modest) and then backpedaled by explaining that she knew this word because she once had an Orthodox Jewish lover. It was a brilliant save that was fully in character, yet it cost the discussion of the play some momentum. Similarly, the conversation got off to a rather slower start than some may have hoped because instead of immediately delving into the substance of Kafrissen’s engagement with Yiddish culture, White instead felt the need (whether in deference to her character or as a courtesy to non-Yiddishist audience members) to start off the discussion by asking Kafrissen the kind of basic questions about her entry into Yiddish culture that seem to feature in every think piece about contemporary Yiddishists. Clearly, there is interest in such general approaches to contemporary Yiddish, and audiences may be interested in learning more about the personal motivations of a playwright. Yet Kafrissen has written a play that fully backs up her own ambitious cultural objectives—why not use her time to probe the depths of the world she created?

Rae Lynn Caspar White (Iris Bahr) and Rokhl Kafrissen

Such quibbles with the post-show discussion simply serve to underscore the richness of Shtumer shabes. It is a delightful, timely, and thought-provoking play that will hopefully be available to audiences in future readings and stagings, whether online or (eventually) in person.