Shtumer shabes: A New Play by Rokhl Kafrissen

Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Seigel

Rokhl Kafrissen is a journalist and playwright in New York City. Her work on new Yiddish culture, feminism, and contemporary Jewish life has appeared in publications all over the world, including Haaretz, Jewish Week, The Forward, Hey Alma, Lilith, and the DYTP. She conducts the twice monthly Rokhl’s Golden City column for Tablet, which focuses on Yiddish and Ashkenazi life in all its incarnations.

Rokhl was recently awarded a 2019-2020 LABA Fellowship at the 14th Street Y. We sat down with Rokhl to talk about her LABA Fellowship project, a play titled Shtumer shabes (Silent Sabbath). The play was supposed to have its premiere on April 2 as part of LABA Fest. Due to current events, the festival will be rescheduled, pending New York’s recovery from the current pandemic.

Description of the Play

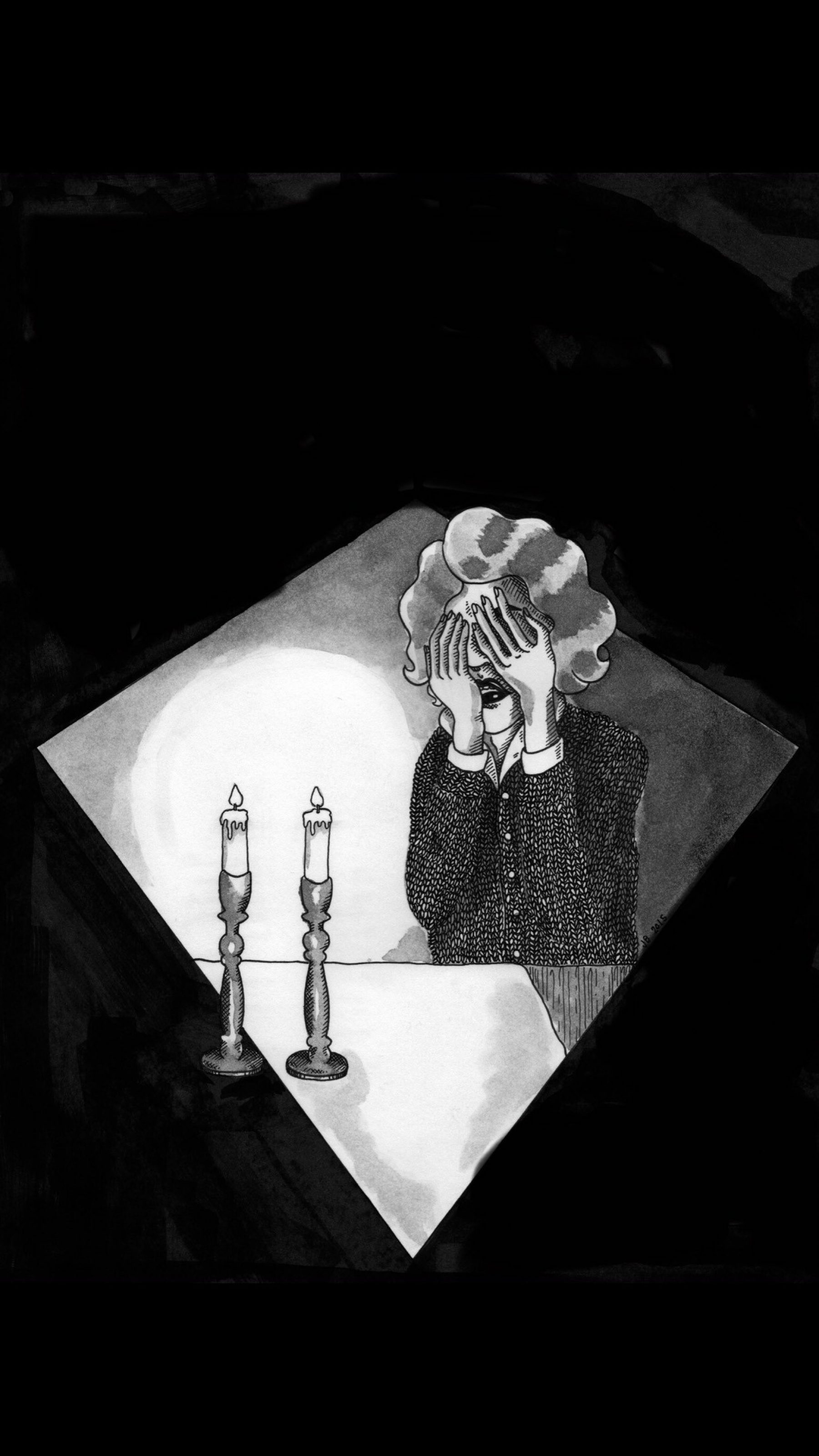

Jess is a twenty-five-year-old performance studies grad student, desperate to make an important research find (and to win the approval of her advisor). Sonja is a ninety-something Yiddish theatre diva with an East Village co-op crammed full of priceless historical documents. Jess believes that Sonja possesses a lost avant-garde Yiddish play called Shtumer shabes, a play that could help Jess rewrite Yiddish theatre history. Sonja may have the play, but first she must decide if she’s ready to uncover the past in which it was lost. These two women, from vastly different worlds, discover that each needs something from the other, but what exactly that “something” is ends up surprising them both.

Miryem-Khaye: What inspired you to write the play?

Rokhl Kafrissen: It’s hard to say if there’s one specific thing that inspired it. In general, my being part of the Yiddish theatre scene as it exists today is obviously a huge part of it, having done supertitles for many Yiddish productions over the years. I am also interested in how the many aspects of Yiddish theatre and performance have been transmitted between generations, specifically as it progressed for my friends and colleagues. That transmission has not been a part of my life, and that’s something I do feel regret over.

In a way, the genesis of the play is both me being intrigued by that intergenerational dynamic, but also imagining what it might have been like for me.

M-Kh: How did you create your characters in the play? Do your observations or experiences in the Yiddish world shape these characters?

RK: I knew I wanted it to be a simple cast, with an older person and a younger person, and that the older person would definitely be a woman, because I was inspired by my friend Shane Baker’s mentorship with women like Mina Bern and Rozka Alexander.

M-Kh: I am fascinated by the idea of a shtumer shabes custom, where did you get this idea?

RK: It basically comes from my interest in folklore, especially folklore of the British Isles. It’s based on what is believed to be an ancient Celtic tradition called the “dumb supper.” Today it has been adopted by modern practitioners of wicca and neo-paganism. The “dumb supper” was done on Halloween, and you offered food to the departed. I like the idea of a silent meal, which would be really hard for Jews.

M-Kh: I know that women and certainly LGBT folks have been historically underrepresented, if represented at all, in Yiddish theatre history. So I am excited to see that this play centers on strong female characters and touches on LGBT themes.

RK: I knew I wanted to have a woman at the center. That part was easy. As for LGBT themes, frankly, when writing a play, even more so than with other creative projects, you need to draw on real life to make it sound and feel believable. In real life, my closest friends are queer, so of course some of the people in my play will be queer.

The representations of people who actually do Yiddish aren’t always terribly accurate. It was important to me to write something that would give a real snapshot of what it’s like to be a Yiddishist in the twenty-first century, and part of that is the queer flavor of modern Yiddishism. There is nothing remarkable about it, it just is.

M-Kh: I know that you are also a cultural critic, writing a regular column for Tablet, as well as for other publications. How does cultural criticism influence your approach to the play?

RK: Going from being a critic to the producer of a piece of art is a pretty harrowing experience because it’s time to put your money where your mouth is. And I would say I certainly went into the project with a sense of what other people had not gotten right and what I wanted to get to right.

M-Kh: What did they get wrong?

RK: People from the outside are drawn to writing about Yiddish, but they insist on applying the same themes over and over. Nostalgia, revival, the idea of talking to our grandparents, the Holocaust as an undefined horror looming over us. These are all elements of our lives, of course, but it’s all interwoven. People on the outside looking in tend to want to impose a lachrymose, backward-looking narrative onto our lives and work, but I find Yiddishists to be a very positive, forward-thinking group of people.

M-Kh: What do you want to get right?

RK: I want to honor first of all the artists of the early twentieth century as human beings and fallible people, and not look at them through a nostalgic or lachrymose lens—“oh, they all died”. But how did they live?

I hope I’m acknowledging the complexity of history. I think I said this at the beginning, because in my role as a critic, I try my hardest to make sure my facts are correct. It’s important to me to be precise in my critical work. But in my artistic work, I have taken some liberties with historical facts and I am a little bit nervous about that. My inner circle will know what’s correct and what’s a product of artistic license, but of course not everyone will know what’s based in fact and what’s invented. But then I think about Peter Schaffer writing Amadeus, and basically rewriting history, and I’m not that concerned. The play isn’t a history lesson, but an investigation into Jewish life inspired by historical materials.

M-Kh: What is it like being part of an artistic cohort at LABA: A Laboratory for Jewish Culture at the 14th Street Y?

RK: I really like it. It’s been amazing. There is a text study every month, led by Ruby Namdar, an Israeli novelist who has opened up the narrative world of gemore and Tanakh to me. On a practical level, for example, one of the LABA cohort folks helped me find an actor for the play. Until now, I’ve had my artistic circle mostly composed of talented Yiddishists. Now that circle has expanded in so many new directions.

M-Kh: What audience do you hope to reach?

RK: I hope to reach a wide audience, not just a Yiddish theatre audience, although I would say I have a lot of love for that audience. They will understand the time and place I am evoking, but I don’t think you have to be one of those people to enjoy it. And I would be happy if someone got interested in Yiddish theater because of it.

A reading of Shtumer shabes was scheduled to take place on Thursday, April 2, at 7:00 PM at the 14th Street Y, featuring Dylan Seders Hoffman, Caraid O’Brien, and Max Roll. It has been postponed.