Henry James, circa 1905. New York Public Library, Digital Collections.

Henry James: The Yiddish Stage in The American Scene

Judith Thissen

In late August 1904, Henry James returned to the United States after an absence of twenty years. Upon arrival in New York, he was overwhelmed by the first views of Manhattan and the “change of things” in his native city. The impression of the modern metropolis with its skyscrapers and multitude of “foreigners” was so profound that he was almost gasping for breath. He was not the only person who was excited. The city’s cultural elite was thrilled to have the famous writer in their midst again. If we ought to believe the New York Sun, even on the Lower East Side plans were made to give Henry James a warm welcome:

Among the many persons here who are anxious to honor him is Jacob M. Gordin, the Yiddish author … will arrange a special performance of his play “God, Man and Devil,” for the novelist.

New York Sun, August 31, 1904.

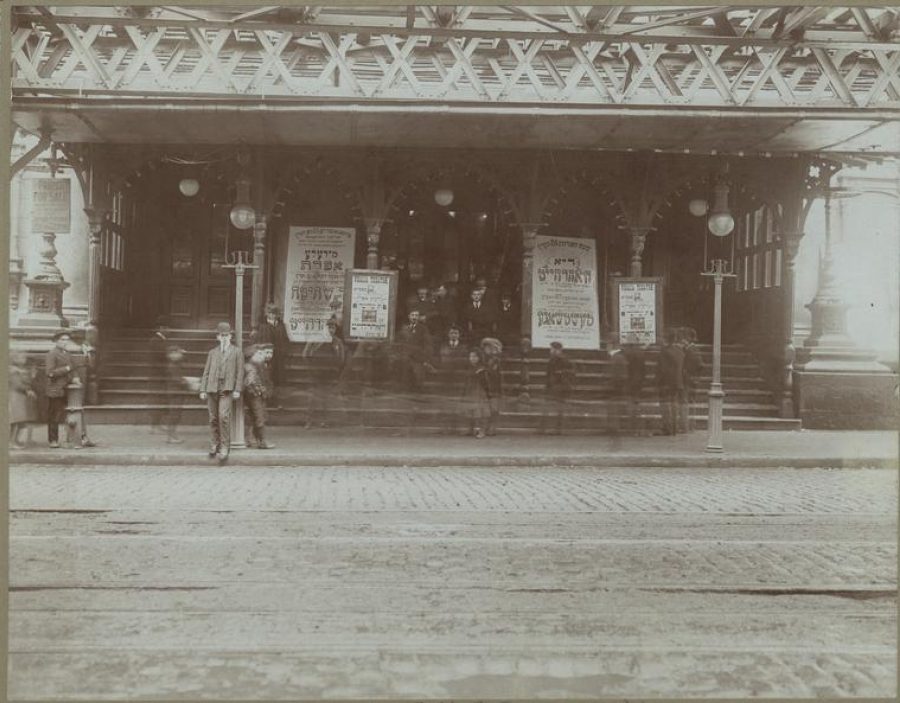

We don’t know why Gordin wanted to invite James to the downtown Yiddish theatre district to see one of his classics. It is unlikely that their paths had crossed before. The question is: did they ever meet? Did James attend a performance of Gordin’s much celebrated reworking of the Faust legend, or any other Yiddish play? When Gordin gave a benefit performance of Got, mentsh un tayvl at the Thalia Theatre on the Bowery in February 1905 to raise money for the Russian revolutionaries, the New York newspapers covered the event in detail, but the press did not mention a single word about the presence of Henry James.

Whoever expects to find the answer to this question in The American Scene (1907)—the book about the author’s 1904/05 trip through the United States—will be disappointed. In his travel journal, James remains very vague about the people he met and the places he visited during his outings to the Lower East Side, which are recounted in chapter five (“The Bowery and thereabouts”). This vagueness has been subject to many interpretations, but I have yet to see a map that shows where Henry James really went. Recently, literary scholar Peter Collister, who is preparing a commented edition of The American Scene, asked me to help him reconstruct James’s ventures into the Yiddish theatre district.

The first task was to see what information I could gather about these outings from the journal itself. I must admit, this was quite a challenge, and not only because James is so extremely elusive. Reading the chapter about his trips to the Bowery, I learned more about the author’s deep anxiety about Jewish immigrants and other newcomers than about Yiddish culture in the early 1900s. Unlike Hutchins Hapgood, James had very little affinity with the Spirit of the Ghetto. Still, it is important to get the facts straight.

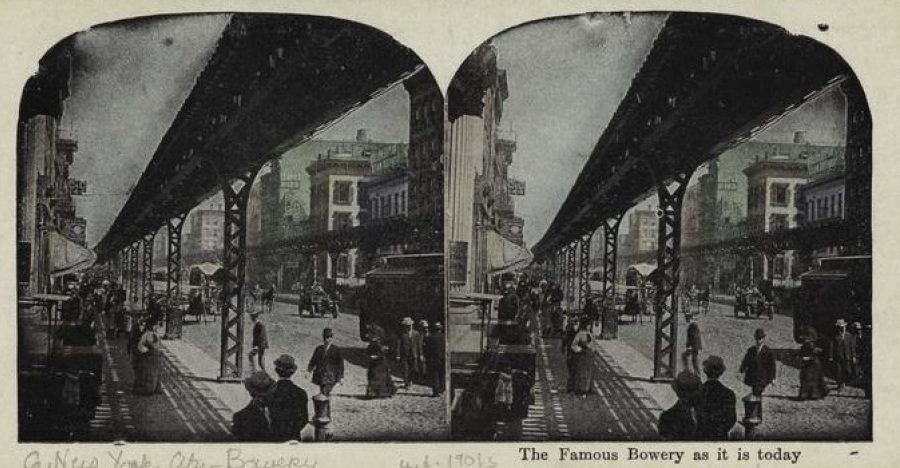

“The Famous Bowery as it is today.” Stereopticon view, early 1900s. New York Public Library, Digital Collections.

The American Scene describes two outings to the Bowery. The first took place on a Saturday afternoon in “midwinter,” when James attended a “domestic drama” at the Windsor Theatre (37-39 Bowery) to see a young actor who had caught his interest. It would have been helpful if James had mentioned the name of the actor or the title of the play in which he appeared. He does tell us, however, that it was a melodrama in which the villain “ends up being trapped in a folding bed engulfed as in the jaws of a crocodile.” Jewish immigrant audiences loved this sort of spectacle. It sounds like something out of a play by “Professor” Moyshe Hurwitz, who excelled in crazy plot turns and wild endings. Yet, it was not a Hurwitz production, as some scholars assumed. For several years, Hurwitz had managed the Windsor Theatre, but with increasing difficulty due to growing competition and an outdated repertoire. In October 1904, his company collapsed as a result of the unwise decision to change from operetta to serious opera in Yiddish to attract larger crowds. Hurwitz went bankrupt and the Windsor went dark. On November 1, the American impresario and Broadway producer A.H. Woods took over its lease for the remainder of the season. What Henry James saw at the Windsor in the winter of 1904/05 was a ten/twenty/thirty cent melodrama in English!

I seemed to see the so domestic drama reach out to the so exotic audience and the so exotic audience reach out to the so domestic drama. The play … was American, to intensity, in its blank conformity to convention, the particular implanted convention of the place.

Henry James, The American Scene.

That James did not see a Yiddish but a mainstream American play at the Windsor sheds a different light on this section, calling into question earlier interpretations. However, this does not make James’s reflections upon his theatrical experience on the Bowery less interesting, especially his ideas about the potential impact that American melodrama, with its blatant lack of realism, might have upon the “so exotic audience” with “Hebrew faces.” What this section of The American Scene also reveals is that in the early 1900s, there already was a considerable Jewish immigrant audience for English-language plays. Not a small clientele, but one that would fill the 3,500-seat Windsor Theatre.

In the summer of 1905, Henry James returned to the Lower East Side for a second visit. According to his travel journal, he was accompanied by “two or three friends,“ who were to show him some of “the most ‘characteristic’ evening resorts” in the neighborhood. The slumming tour started in a loud working-class German beer cellar “adorned with images of prize strong men and lovely women.” The other places were “mostly higher in scale.” They also stopped at a Yiddish playhouse.

There was also, as I recall, a snatched interlude—an associated dash into a small crammed convivial theatre, an oblong hall, bristling with pipe and glass, at the end of which glowed for a moment, a little dingily, some broad passage of a Yiddish comedy of manners.

Henry James, The American Scene.

James and his friends quickly left because of the filthy air, but he could get neither the image nor the smell of the place out of his mind. Unfortunately, the journal does not give any further details about the location or play, which makes it an even bigger challenge to find out what exactly happened. Beth Kaplan, the great granddaughter of Jacob Gordin, suggests that they had a glimpse at a performance of Di varhayt (The Truth), one of his latest works. But I found no evidence to support this. Gordin’s play was part of the repertoire of the Thalia Theatre, which was a 3,000-seat playhouse, where smoking in the auditorium was forbidden by municipal fire safety regulations. Also, by the time James returned to the Lower East Side, the three Yiddish legitimate playhouses in downtown Manhattan had already closed down for the summer. Usually, the big stars of the New York Yiddish stage went on tour after Passover and they either subleased their theatres to English-language companies or simply shut the doors. Put differently, I think it is safe to say that on his second outing to the Bowery, James—once again—did not see a Yiddish drama.

Thalia Theatre 1904 with bill boards for Mirele Efros and Di Varheyt by Jacob Gordin. New York Public Library, Digital Collections.

So where did the friends go? I think that they visited a Yiddish variety theatre, which was the latest novelty in the American-Yiddish entertainment business and definitely something to show on a “look-in” at immigrant “haunts.” It might have been the People’s Music Hall on the Bowery, but that was still a relatively fashionable place. More likely, it was a concert saloon in the heart of the Jewish quarter, like the popular Irving Music Hall on Broome Street. These cheap entertainment venues remained open during the summer and admission was often free on the understanding that the customer ordered at least a glass of beer. The Yiddish comedy of manners at which James looked “as through a spy-glass” was probably not much more than an elaborate vaudeville sketch.

Whose idea was it to take James to such a place? In my view, Jacob Gordin seems an ill-suited candidate. For many years, the playwright had struggled to improve the standard of the Yiddish stage, fighting shund (popular plays; literally “trash”) and promoting “emese kunst” (true art). It makes no sense that he would take his honorable guest to a Yiddish music hall to see a bawdy variety act. Robin Hoople suggests that it was district attorney William T. Jerome who organized the trip to the East Side. 1 Jerome was a notorious anti-vice crusader and indeed the right man for the job of showing “low-life” on the Bowery and beyond.

Henry James, Jacob Gordin—it was “the most unlikely literary couple in the history of the city,” according to Stefan Kanfer. They were indeed a most unlikely couple. And they probably only met in fictional accounts of Yiddish theatre history.