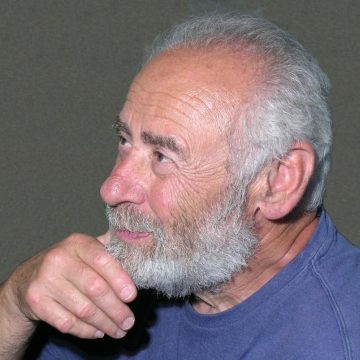

Annick Prime-Margules (Eti-Meni) and Michel Fisbein (Shimele Soroker) in the Troïm-Teater's adaptation of Sholem Aleichem's Dos groyse gevins (The Jackpot).

The Troïm-Teater and Contemporary Yiddish Theatre in Paris

Alexandre Messer

“A sheynem gutn ovnt aykh, mayne libe layt” – With this greeting at Théâtre Déjazet on January 24, 2004, Yiddish theatre was back in Paris, after a long, long absence. This performance, which was of Haim Sloves’s Di yoynes un der valfish (Jonah and the Whale), was the first performance of what is now known as the Troïm-Teater, currently the only active Yiddish troupe in Paris.

The history of Yiddish theatre in France and in Paris after World War II goes beyond the scope of this piece. However, some background in in order. After emerging from the horrors of the Occupation, Vichy, and the Holocaust, the Parisian Jewish cultural community was still deeply rooted in Yiddish. Yiddish could be heard in stores, workshops, cafés, and on the streets in the so called “Jewish” neighborhoods of Paris, such as the Marais and Belleville. There were Yiddish newspapers and periodicals, and publishers printed Yiddish books written by local Yiddish writers. Hometown associations (landsmanshaftn) from different locations in Poland and Russia conducted their activities essentially in Yiddish. And there were Yiddish theatres, which gave regular performances of plays from the Yiddish repertoire. Most notably, the interwar Yiddish theatre troupe Parizer yidisher avangard teater (PYAT/Parisian Yiddish Avant-garde Theatre), which emerged shortly after the end of World War II for one performance, would eventually become the group the Yidisher kunst teater (YKUT/Yiddish Art Theatre) and run from 1945-1949. Also active during these years was the troupe Yidisher folks-teater (Yiddish People’s Theatre) and the puppet theatre troupe, Hakl-Bakl (1949-1952). During the 1960s, Paris hosted the Parizer yidisher teatre-ansambl (Parisian Yiddish Theatre Ensemble). As during the interwar years, Yiddish troupes from abroad also visited and performed in Paris.

As the years passed and the post-World War II generation assimilated into French culture, Yiddish, and the associated cultural activities, started to vanish. The younger generation often heard Yiddish in their homes, sometimes even spoke it, and some even read and wrote it, but, in general, the postwar generation in France was seemingly not interested in Yiddish culture. The newspapers and publishing houses started closing down, and theatre troupes, after losing their public, were also forced to close.

Since 1970, Yiddish theatrical performances have been few and far between. There were some play fragments performed on different occasions through the early 1980s by the few Yiddish actors remaining in Paris. But, until the Troïm-Teater, there was essentially no contemporary Yiddish theatre in Paris.

Charlotte Messer directing Homens mapole.

The Troïm-Teater

The “adventure” of the Troïm-Teater started in 1999 when Charlotte Messer, the art director and creator of the troupe, felt a need to get back to her Yiddish cultural roots. Charlotte used to speak Yiddish in her family, but she never learned to read or write it. She enrolled in a Yiddish class at the Maison de la culture yiddish – Bibliothèque Medem for “false beginners,” a class meant for people who could understand and speak Yiddish, but could not read or write using the alef-beys (alphabet).

It was her teacher, Renée Kaluszynski, who suggested that Charlotte develop a theatre workshop in Yiddish, as a way for her to help improve her Yiddish. Within the workshop emerged a group of gifted and motivated people to whom Charlotte taught the basic elements of drama. After three years of work, in early 2003, she felt the group was ready to stage a full play. Among the several texts considered, Haim Sloves’s Di yoynes un der valfish was selected as the first production. This was a statement: Troïm-Teater wanted to assert the link between the Yiddish theatre and one of its original sources, the purimshpil.

Charlotte set a challenging goal: In contrast with some earlier amateurish attempts, the staging had to be of professional quality and played on an actual stage in an actual theatre for an actual, paying audience. In order to accommodate a non-Yiddish-speaking public, she decided to explore the possibility of using supertitles–widely used by operas–but rather exceptional in theatres in France at that time. For set scenery, she adopted Peter Brook’s minimalistic aesthetics of an empty stage with limited props and costumes defining the place, the nature, and the time of action. The staging was a success, and the group decided to continue the adventure by establishing an actual theatre troupe. It was during the work on its next play, a version of Avrom Goldfaden’s Di tsvey kuni-leml (The Two Kuni-Lemls), that the group chose the name Troïm Teater – theatre of dreams.

At approximately the same time, two Yiddishist organizations in Paris, the Medem Bibliothèque and the Association for Studying and Propagating Yiddish Culture (AEDCY) merged to create the Maison de la culture yiddish. Naturally the nascent Troïm-Teater became an integral part of this new institutional addition to Yiddish Paris.

Since 2004, the troupe has produced five plays. Di yoynes un der valfish was performed three times in 2004 and 2005 in Paris, and Di tsvey kuni-leml was performed seven times in Paris in 2007/2008, and twice in Vienna in November 2008. Between 2010 and 2012, the troupe staged Sholem Aleichem’s Dos groyse gevins (The Jackpot) ten times in Paris, Lyon, and Metz, and twice in Montreal as part of the 2011 International Festival of Yiddish Theatre. Haim Sloves’ Homens mapole (Haman’s Defeat) played six times in Paris and twice in NYC during the 2015 Festival of Jewish Performing Arts, and twice in Metz in 2016. Boris Sandler’s monologue Afn halbveg fun benkshaft (Halfway to Longing) was performed ten times between 2014 and 2016 in Paris, NYC, Brussels, and Strasbourg.

Five plays in twelve years might not seem like a lot, but the troupe struggled with several issues during the development of its repertoire: issues perhaps common to other Yiddish theatre troupes anywhere in the world operating in a similar environment. I will list and discuss those issues here:

Michel Fisbein (Shimele Soroker) and Annick Prime-Margules (Eti-Meni) in Troïm-Teater’s adaptation of Sholem Aleichem’s Dos groyse gevins.

Annick Prime-Margules (Eti-Meni), Betty Reicher (Vigdortchuk), and Michel Fisbein (Shimele) in Dos groyse gevins.

Charles Perelle (the horse), Marion Blank (Mezumen), Lionel Miller (Mordekhay), Laurence Fisbein (Esther), Jeannette Kohn (Memoukhen), and Michel Fisbein (Ahashverosh) in Troïm-Teater’s adaptation of Haim Sloves’s Homens mapole.

Annick Prime-Margules (Libele), Lionel Miller (Max), and Charles Leizorowicz (Kuni-Leml) in the Troïm-Teater’s adaptation of Avrom Goldfaden’s Di tsvey kuni-leml.

Charles Leizorowicz (Kuni-Leml) and Lionel Miller (Max) in Di tsvey kuni-leml.

The final scene of Di tsvey kuni-leml. The photographer: Léon Kaluszynski z”l. Top row: Lionel Miller, Laurence Fisbein, Victor Lebenstein, and Mireille Sikari-Zolty. Bottom row: Shlomo Zilberman, Alexandre Messer, and Dorothée Vienney.

Recruiting actors. It was (and still is) difficult, if not impossible, to find trained, professional actors with sufficient fluency in Yiddish. We never explored the possibility of actors who would be willing to learn the language, or at least the parts, for any of the plays. For our purposes, we did not think it was relevant. We might consider such a path in the future, but this would require a totally different approach, mostly in terms of finances.

The choice was to go with gifted and motivated non-professional actors (I avoid the term “amateurs” because of its somewhat disparaging sense) that could be trained within the group. We required, however, that everyone be fluent in spoken Yiddish and capable of reading the text of the play without transliteration. When we started, our youngest actress was in her early forties; the oldest actor was in his seventies. In 2016, during our last production of Homens mapole, the average age of the troupe was 70: the youngest person was 55 and the oldest 82. The average age has been going down recently, as some new young members have joined the troupe and some of the older actors are retiring.

Attracting young talents to any enterprise in Yiddish, and specifically theatre, is a great challenge, and I must admit that in this respect we have not been very successful.

Time. Some of our actors are retired, but some others are still active in their different professional occupations, which puts limits on their availability. Furthermore, although acting is our pleasure, it is neither our only activity nor our sole objective in life. This limits the number and duration of performances and rehearsals, and it can sometimes make planning a challenging task. This is also one of the reasons for the relatively long time between productions.

Repertoire. We have set for ourselves a mission of producing dramatic works only by Yiddish authors and of playing exclusively in Yiddish. Working with the existing repertoire involves two limitations: the number and nature of available actors (male/female, age) and pertinence of the text. Although the main social or societal issues addressed by most of the plays are still relevant, some others are outdated or need to be reformulated. There is also some work with the language: there are many words and expressions, customarily used by Yiddish speakers of the past, often related to religious life, that are no longer relevant to today’s essentially secular public. Therefore each text requires extensive reworking, sometimes rephrasing; we also always shorten the plays. Many of the plays were originally written for performances that took three to four hours. We always stress in our publicity materials (or communications) that the plays are “based on” a given author’s work, and not written by the author. The reworking of a text is, as any art director knows, a lengthy process that takes several months, sometimes over a year.

Public. According to our experience, the Paris audience for Yiddish plays numbers between 1,200 and 1,500 individuals. Less than a quarter are Yiddish-speakers of the older generations. A significant part of the public are non-Jews who are attracted to Yiddish culture. Therefore the super-titles are essential, and we have made great efforts to make them easy to read and follow perfectly in sync with the play. It is probably possible to attract a larger non-Jewish public among theatregoers; this would, however, require a more intensive public relations campaign and a longer series of plays, something we can not afford within our current financial structure.

Venues and facilities. Renting a theatre in Paris is a difficult and expensive proposition. For the most part, they are fully booked one to two years in advance, by professional troupes, for long series of performances. Finding a house that is willing to accept a small troupe playing in a “strange” language for a few performances and for a reasonable fee has always been a challenge. For most of our performances, the Maison de la culture Yiddish makes the advance rent payments and provides help with communication and advertising. All of our performances have provided sufficient revenue to reimburse the Maison and make a small profit. The availability and price of the venue is the main limiting factor of the number of performances for any given play.

The other issue has been rehearsal space, at least until 2010, which was when the Maison de la culture Yiddish moved to its present, larger location. On average, we have a three-hour time slot for rehearsals every week, unless there are school vacations or other holidays, or the actors or the space are not available. Considering all of these factors, our average time to produce a play is over two years.

Finances. We have had some limited subsidies from institutional or private donors, which went into the Maison’s common budget. A significant part of our costs was covered by the proceeds from performances. Nevertheless, the activities and the very existence of the troupe were made possible thanks to the unpaid work of all of its members. None of our members, including Charlotte, the artistic director, draws a salary. On the contrary, we all make regular financial contributions simply for the pleasure of acting and for being members of the troupe. Almost all of our costumes and stage props are custom made free of charge, with some minor expenses for raw material.

Yiddish dialects. In the early stages of work, we realized that our pronunciation habits are not uniform. Most of us speak the Polish dialect, since most of the Yiddish-speaking population in Paris came from Poland. Those who learned the language as adults use the “standardized” YIVO pronunciation, which is closer to the “Litvak” dialect. We tried the “Volhynian” Yiddish, which was the standard of the prewar Yiddish theatre, but were not successful at that. The tradeoff we made was that everyone would use his/her own language, since this is the actual way we speak nowadays in Paris. We call it Parisian Yiddish. It does not make much difference for those who do not know the language, but it can occasionally be disturbing for some Yiddish-speakers.

The future. After a busy 2015/2016 season, the troupe is working on some new projects for the 2017 and 2018 seasons. New forces have been recruited and new paths are being explored, both in terms of repertoire and artistic approach. The major goal, however, is the same: to be a permanent Yiddish theatre troupe.

Miller (Mordkhe), Charles Perelle (Horse), Alexandre Messer (Homen), and Jeannette Kohn (Memoukhen) in Homens mapole.

Other troupes and events

In 1992, in Strasbourg, the very talented professional actor Rafi (Rafael) Goldwasser with the help of a group of local Yiddish-lovers created a Yiddish theatre under the name of lufteater – Theatre in the Air. Over the past twenty-five years, he has created and performed many interesting Yiddish plays, mostly monologues from the literary heritage of the greatest Yiddish writers: I.L. Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, I.B. Singer, Itzik Manger, and others. He has performed in many places around the world and in many festivals. Unfortunately, performances in Paris were rare. This theatre is worthy of its own monograph.

In 2015, a French director, Benjamin Lazar, created a French-language version of An-ski’s Der dibek (The Dybbuk), but with some parts also spoken in Yiddish or Hebrew. The play was produced in Paris and played in many places across France. It was well-received by critics.

The Centre Medem – Arbeter Ring runs a Yiddish theatre workshop under the direction of Yael Tama, Michele Tauber, and Erez Lévy. In 2015, the workshop performed a one-time, original Yiddish play titled Esterl mayn libe (Esther my love) at the Cercle Bernard Lazare and a purimshil based on Itzik Manger’s Megile lider (Songs from the Book of Esther), which they performed at the Centre Medem. They will also perform another original, Ay mamushka! (Hey Mom!), later this year.

The Pourimshpil Collective.

A number of Yiddishist associations, under the leadership of the Centre Medem and of the Maison de la culture Yiddish – Bibliothèque Medem, initiated a project to inscribe the purimshpil on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. An important milestone was reached with the inscription of the purimshpil on the List of the French Intangible Cultural Heritage. Currently the Pourimshpil Collective, an umbrella organization of participating associations, is working to secure support of other European countries, which have or had a large Jewish population, in order to collectively present it to UNESCO, probably in 2018.