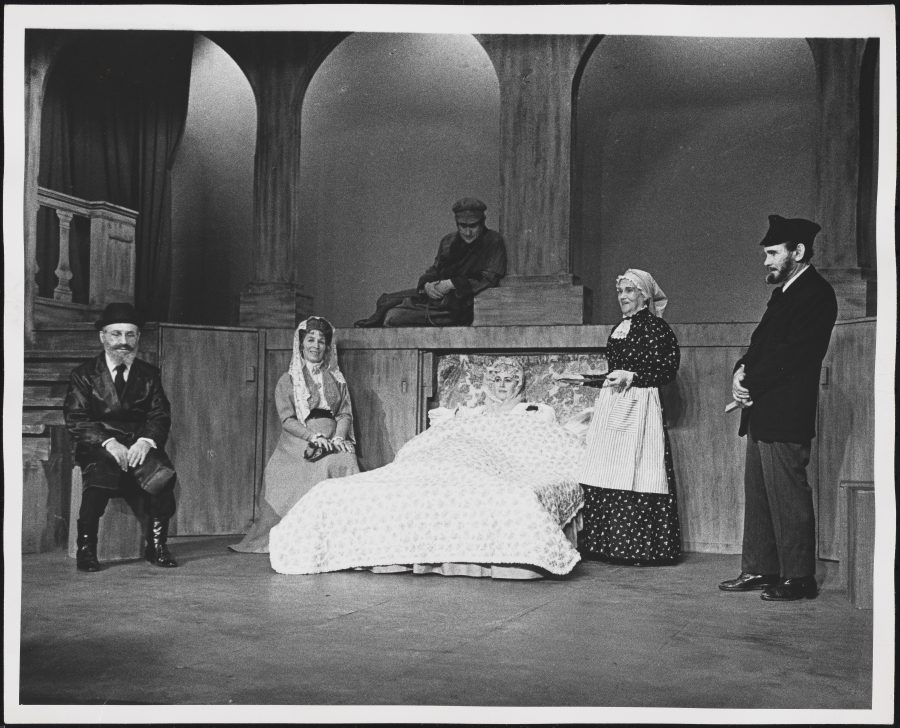

Yoshe Kalb theatre still. Rappoport/Museum of the City of New York.

A Yiddish Musical That Never Was

Leon Gildin

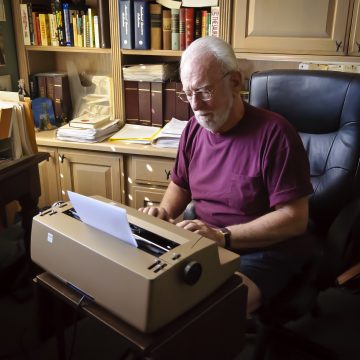

In thinking back over the many years in which I have been involved with theatre, particularly the Yiddish theatre, there are two specific things that I must call to the attention of the reader. The first: during those years I was a practicing attorney in New York and many of the individuals became not only friends, but clients. The second is Camp Boiberik, the summer camp of the Sholem Aleichem Folks Institute, where I was both a camper and a counselor. Camp Boiberik opened in the 1920s and closed in 1979, and if you will indulge a momentary digression from the topic, allow me to illustrate the importance of this camp for our subject.

On a summer’s evening in the late 1980s, I stood on the steps of the dining room at the Workmen’s Circle Camp in Hopewell Junction, N.Y., with Harold Ostroff, whose many leadership positions included General Manager of the Forward Association and President of the Workmen’s Circle, and watched the children, dressed in white for Shabbos. I expressed my disappointment that Boiberik had to close while the Circle camp was still going strong, to which Harold replied, “It had to close; you were too Jewish.” Sadly, he had a point. Camp Boiberik’s insistence on maintaining some of its founding principles, like requiring counselors to be Yiddish speakers, proved unsustainable in the long run.

Ben Bonus, Mina Bern, Shifra Lerer, and Zypora Spaisman, who was the nurse for the children’s camp, performed on weekends. During the winter, all of these performers could be seen on the stage of the Folksbiene along with Lillian Lux, wife of Pesach’ke Burstein and mother of Mike Burstyn. Lillian was kind enough to read a work that I had written, and her comments and suggestions were correct and meaningful. In addition, there was Sandy Levitt, a dear friend and client, treasurer of the Hebrew Actors’ Union, and young enough to play “the kid” where one was necessary, or the love interest — until his hair started to turn gray. The Folksbiene would later come under the direction of Zalmen Mlotek. His father, Yosl Mlotek, was head of Jewish Education at the Workmen’s Circle, but his mother, Chana Mlotek, then the music archivist at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, had been known as Honey Gordon in her camp days at Boiberik. Chana insisted that Zalman and his brother both go to Boiberik.

Camp Boiberik Alumni

Going on to Hollywood, I last spoke to David Opatoshu—the actor son of noted Yiddish writer Joseph Opatoshu—by chance at the airport in Paris, France. And if a film ever needed an old, Jewish hunchback, they cast a longtime client, Leib Lensky. Although I did not know Joseph Buloff personally, after his death his wife, the well-known Yiddish actress, Luba Kadison, was introduced to me by another longtime friend and client, Joe Singer, son of I.J. Singer and nephew of Isaac Bashevis Singer, who had translated both his father’s and uncle’s work from Yiddish to English. Buloff had written a novel entitled From the Old Marketplace, and Joe asked me to negotiate the publication of the book on behalf of Luba with Harvard University Press, which I did.

When it came to music, I am proud to say the renowned singer, Sidor Belarsky was a close friend of my parents, and I had the pleasure of translating some of his songs from Yiddish to English. His accompanist at many concerts was the well-known pianist and composer, Lazar Weiner, who was the music counselor in Boiberik for many years (and the band leader at my first wedding), followed by musicologists I. Trilling and Vladimir Heifetz. In later years I knew and represented “the Frank Sinatra of Russia,” Emil Gurevitch.

Many of these names might be unfamiliar today but they were talented, well-recognized performers in their day. Unfortunately, with the exception of Mike Burstyn, none of them are with us today. But let me tell you the story of a noteworthy lunchtime meeting with several of these figures, and of a Broadway musical that might have been.

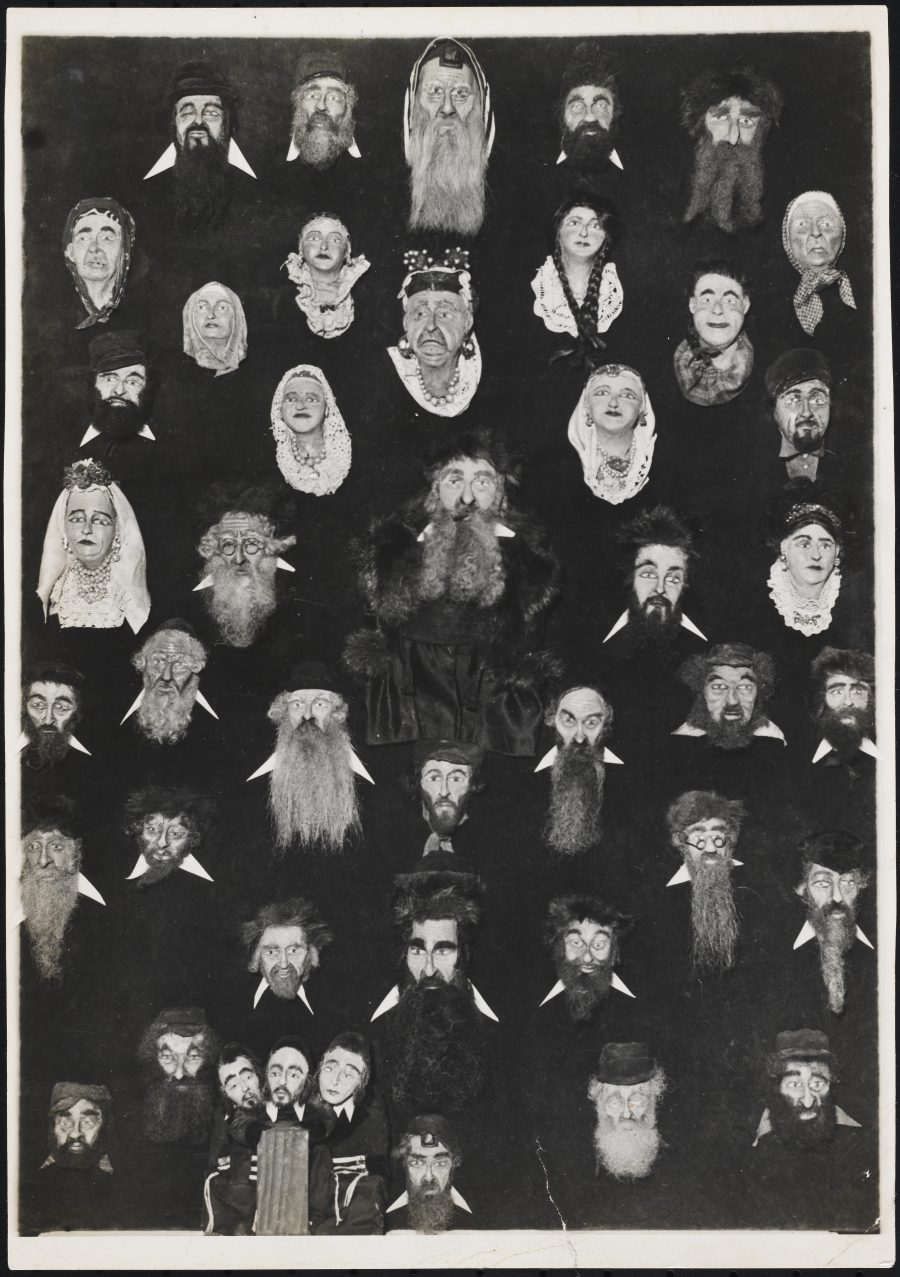

Artistic representations of characters from Yoshe Kalb on exhibit at YIVO. Photographer unknown/Museum of the City of New York.

Lunch at the Russian Tea Room

Sometime in the mid-1970s in New York City, I received a call from a client, Zvi Kolitz, asking if I was free for lunch at the Russian Tea Room. One never turns down such an invitation. The Tea Room was expensive, fashionable, and the place to be seen. Yes, I was free for lunch. I could taste the borscht, the blini, and the tea in a glass. As an aside, permit me to say that the big hit on Broadway, in those days,

At any rate, when I arrived at the restaurant I met the following people. First there was Sidor Belarsky, the renowned singer and interpreter of Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian art songs. Next to him was Sholem Secunda, the composer of many Yiddish songs performed on Second Avenue during the heyday of Yiddish theatre and vaudeville, but perhaps more widely known as the composer of "Bei Mir Bist Du Shein,” made popular by the Andrew Sisters. I knew who Secunda was but had never met him, but by coincidence, I knew his sons, who had played baseball in the same schoolyard that I had when we were kids. Next to him was Joe Singer, the son of I. J. Singer, the famous Yiddish novelist and brother of Isaac Bashevis Singer. Joe did all of the translations of his father’s work, and translated many of his uncle’s stories as well. In the years that followed, Joe and his wife became my clients as well as dear friends, and my wife and I spent a considerable amount of time with them. His wife was a well-known book author, particularly in England, and Joe was, in addition to being a translator, a well-recognized artist and teacher of art.

Menashe Oppenheim, Zypora Spaisman, Mina Bern, unidentified actress, Joshua Zeldis, and Joseph Buloff in The Brothers Ashkenazi. Arnold Chekow/Museum of the City of New York.

One of I.J. Singer’s best-known works was the novel Yoshe Kalb, a disturbing, emotional story of love, betrayal, and deceit within the Hasidic community of Eastern Europe. Joe had adapted the novel for the English-language stage as “Yoshe the Loon.” Given that Kolitz was a producer, and I was an attorney in the theatrical field, Secunda saw it as a play with music that he would write, and Belarsky saw himself in the role of the aged rabbi. So the question put to me was this: could I see it as a Broadway production? My answer was no — not because I thought the play wouldn’t make a dramatic impact, but because we were still overwhelmed by the success of Fiddler. Two plays about Eastern European Jews with beards, across the street from one another, was to me a theatrical impossibility.

Nevertheless, the luncheon was good (I don’t remember who paid), and we all parted in good spirits. To this day I have a copy of the English version of “Yoshe the Loon” in my file cabinet in the hope that perhaps… someday… Unfortunately, other than myself, none of my lunch companions are with us any longer. The novel Yoshe Kalb, however, lives on in both Yiddish and English.