Der dibek, 1975, Israeli Yiddish entertainment posters, 1930-1981, Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University. Wikidata: http://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q101009563

Wikidata, Yiddish Theatre Posters, and the World

Heidi G. Lerner

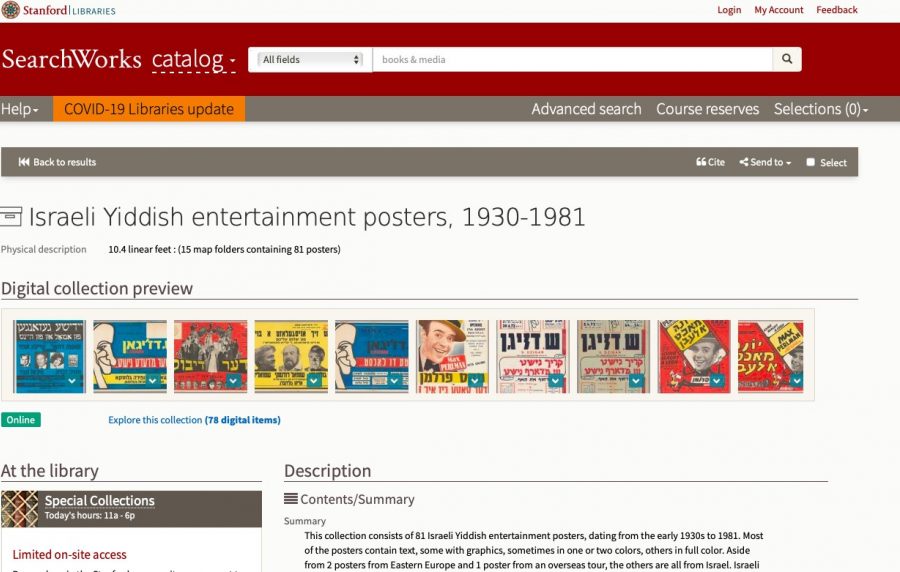

In 2019, Eitan Kensky, the Reinhard Curator of Hebraica and Judaica at Stanford University Libraries (SUL), initiated and coordinated a purchase of a discrete collection of eighty-one Israeli Yiddish theatre and entertainment posters, “Israeli Yiddish entertainment posters, 1930-1981.”

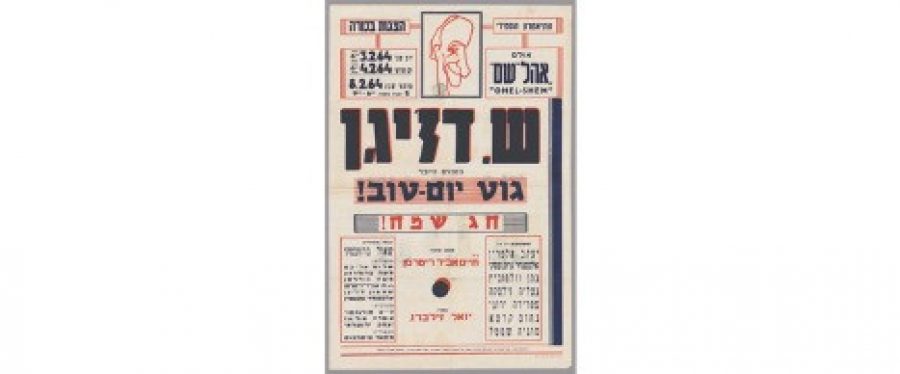

According to the dealer’s description, “This collection consists of eighty-one Israeli Yiddish entertainment posters, dating from the early 1930s to 1981. Most of the posters contain text, some with graphics, sometimes in one or two colors, others in full color. Aside from two posters from Eastern Europe and one poster from an overseas tour, 1 the others are all from Israel. Israeli musicians, performers, authors, playwrights, actors, and actresses represented in the posters include Dzigan and Schumacher (twenty-two posters); Max Perlman (thirteen posters); Sholem Aleichem (various Yiddish productions, mainly by Shmulik Segal, Shmuel Rodensky, and Eliyahu Goldenberg) (eight posters); Joseph Buloff (seven posters); Ben Zion Witler and Shifra Lerer (six posters); Morris [sic] Schwartz (five posters); Henry Gerro and Rosita Londner (three posters); Eni Liton (three posters) and Jetta Luka (two posters).” 2

Stanford’s may be the first collection outside of Israel whose primary focus is on Yiddish theatre productions that appeared almost entirely in Israel. The collection confirms Yiddish scholars Joshua and David Fishman observation that “Yiddish theatre in Israel is very largely restricted to broad musical-comedy and burlesque-vaudeville.” 3 The posters show that in the years following the establishment of the state of Israel and the huge influx of new immigrants, Yiddish theatre in Israel was primarily light and humorous. In Israel Affairs, Rachel Rojanski characterized the repertoire as “light entertainment shows: those of Dzhigan and Shumakher until they split up, and various troupes—some of which came from abroad—that from time to time presented popular musicals. Attempts to establish a Yiddish repertoire theatre, such as that by Anya Liton in 1962, were doomed to failure, as was that of the Goldfaden Theatre.” 4

The collection has three posters from productions starring Eni Liton, identified as the head of the Yiddish Comic Theatre (תיאטרון קומדיה באידיש). In 2016, Diego Rotman noted that despite performing “in a milieu in which a monolingual Hebrew national culture was institutionalized and Yiddish language and culture were officially considered unwelcome,” Dzigan and Schumacher created “the most significant satirical stage presence on the Israeli scene.” 5

Describing the Posters

As Metadata Librarian for Hebraica and Judaica at SUL, part of my job is to make decisions on how to describe resources and collections and make them available to patrons inside and outside Stanford. This collection can serve as a prototype for using new technologies to digitally present information from and about these posters. Ideally, computers and software can enable us to see connections between hundreds of sources. Some of the information that people seek could be easily generated. They might find a list of actors who performed with State Jewish Theatre of Romania and immigrated to Israel, or map the performances of Max Perlman and Gita Galina. Wikidata can aggregate the most frequently performed characters in Yiddish plays and musicals to follow changes in repertoire, and they could cross-reference these with Yiddish theatre posters available in the public domain.

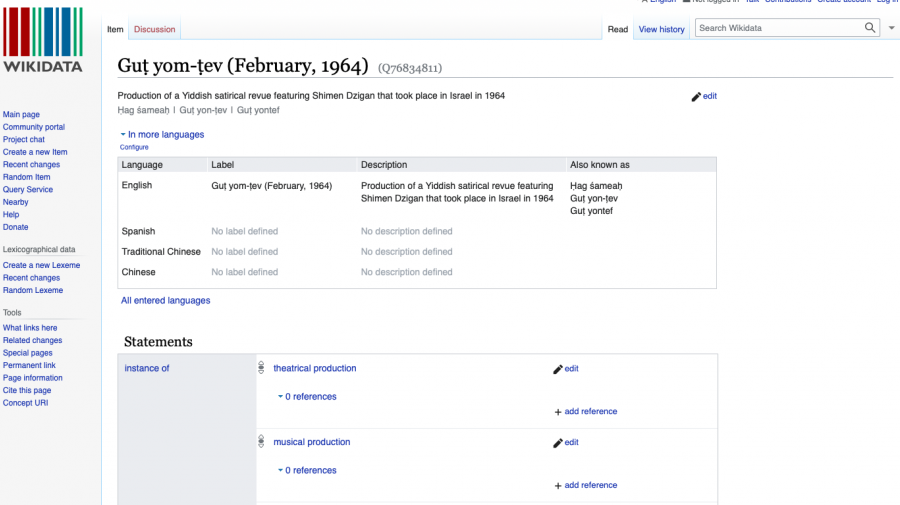

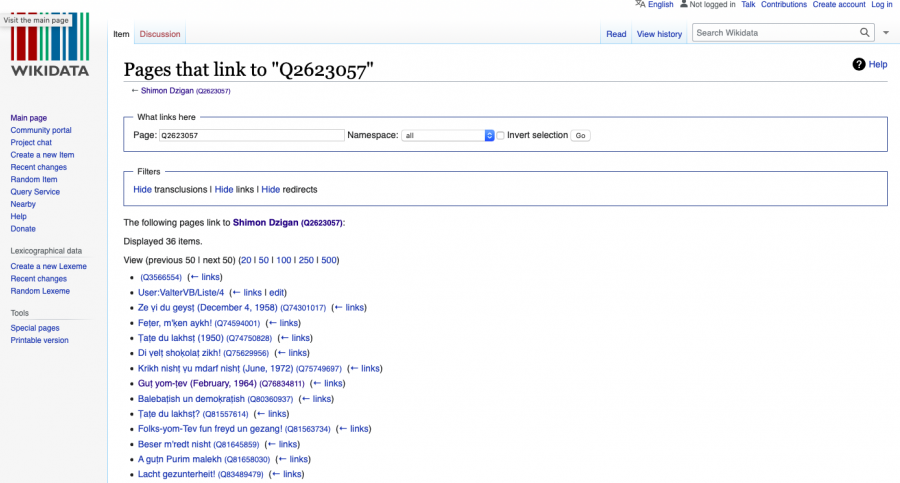

My assignment was to provide catalogue records for each of the posters in anticipation of their digitization. I also created and recorded data related to each poster for a free, public database called Wikidata.

Wikidata is community driven—a crowdsourcing platform of contributors from related disciplines that is not limited to scholars and professional information specialists. Wikidata enables anyone with a love for and knowledge of Yiddish theatre to research, document, collect, and share their knowledge. Contributions to Wikidata include biographical information on actors, directors, scenographers, impresarios, musical directors, lyricists, and choreographers. Wikidata can include textual works and their derivatives, translators, playwrights, venues, and material culture like the posters themselves. The database would include holding institutions and archival repository information, locations, and even shelf marks. My work on this collection has produced two new reference sources on the history of the Yiddish theatre in Israel: the Stanford catalogue records for the individual posters, and the entries added to Wikidata. Both are freely available online.

Because of the poster collection’s chronological and geographical scope, it enlarges the universe of knowledge of dozens of heretofore obscure Yiddish theatre personalities such as ʻAlizah Ḥen (active 1977), Ḥayah’leh Shifer (active 1951), Aleksandr Gronovski (active 1964),

6

as well as the more famous ones including Maurice Schwartz, Shimon Dzigan, and Joseph Buloff. This topic has largely been neglected by Yiddish theatre scholarship and is almost entirely omitted from important reference sources on the subject (especially Zylbercweig’s Leksikon).

7

Expanding the visibility and usability of other Yiddish theatre collections

Libraries, museums and archives that also hold valuable Yiddish theatrical information and artifacts have not made the majority of their resources and scholarship easily available by means in most people’s reach . Materials are often buried in archives, located continents apart. Improving the visibility of Yiddish theatre means making it accessible – available digitally to all. The Stanford library’s new and publicly available data on Yiddish theatre in Israel is entirely created from Wikidata items generated from the posters at Stanford.

The first stage of the project is now complete. I created over 600 pages in Wikidata to enable SUL to share this collection with the rest of the world. My dream is that this is only the beginning of a larger project, one in which any institution, archive, museum or individual lover of Yiddish theatre will engage more fully with digital scholarship and the Wikidata community.

Such a project might include databases such as the New York Public Library Yiddish Theater Collection; the Vilna Troupe dataset created by Debra Caplan; Theatre and Film Poster Collection of Abram Kanof, Center for Jewish History; Polish Yiddish Theater Posters, JDC Archives; Robert and Molly Freedman Jewish Sound Archive, University of Pennsylvania; Yiddish Posters, UWM Libraries Digital Collections; Harvard Yiddish Theater Collections; Sidney Krum Jewish Music & Yiddish Theater Memorial Collection, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research; Israeli Center for the Documentation of the Performing Arts; Moscow State Yiddish Theater, Blavatnik Archive; Israel Goor Theatre Archives and Museum, Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

All of us realize that our collections become more useful and usable when they are deeply interlinked with other collections around the world. Wikidata can connect these databases. I invite my colleagues and scholars to form a task force, or come together as a group to discuss this topic within the community. Participants could include subject specialists, librarians, data scientists and Yiddish theatre lovers in general. Together we can explore and try out new innovative, creative and meaningful ways to expand digitally the presence of Yiddish theatre in all its greatness.

You can read part II here.

Notes

-

1Non-Israeli productions in this collection took place in Paris, Łodź, and Kaunas.

-

3Joshua Fishman, ed., Advances in the Study of Social Multilinguisim (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1974), 229.

-

4Rachel Rojanski, “The struggle for a Yiddish repertoire theater in Israel, 1950-1952,” Israel Affairs 15, no. 1 (2009): 4–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/13537120802574104.

-

5Alekasandr Gronovski (active 1964) is not the same as the Aleksei Granowsky who found the Moscow State Jewish Theatre and died in 1917.

-

6Diego Rotman, “’The Tzadik from Plonsk’ and ‘Goldenyu’: Political Satire in Dzigan and Schumacher’s Comic Repertoire,” in A Club of Their Own: Jewish Humorists and the Contemporary World, eds. Eli Lederhendler and Gabriel N. Finder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 154–170.

-

7Notable exceptions are Diego Rotman, “Ha-Bamah ke-bayit araʻi : ha-teʼaṭron shel Dz'igan ṿe-Shumakher, 1927-1980” (Yerushalayim : Hotsaʼat sefarim ʻa. sh. Y.L. Magnes, ha-Universiṭah ha-ʻIvrit, 2017) and Rachel Rojanski, Yiddish in Israel (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020).