A monument to Hatuey, in Baracoa, Cuba.

Found in Translation: Hatuey, Cuba, and the Jews

Rachel Rubinstein

In 1928, Oyfgang, the first regular Yiddish periodical in Havana, published the following short poem, “Oyfn inzele” (“On the Island”) by M. Gutshteyn, meant to be sung to the tune of “ Oyfn pripetshik”:

Oyfn inzele, vos heyst kuba

Di zun brent do heys

Geyen pedlerlakh mit di kestelakh

Oysgeveykt in shveys

Fargest in yurop mit amerike

Az ir zent in kuba do

Muzt ir onfangen, nebekh, onfangen

Fun komets alef – “o”

Ven ir vet kinderlakh, azoy zikh oppedlen

A tsvey, dray, fir yor

Vet ir im yirtsey hashem, zayn balebatimlakh

Aleyn fun a stor

To pedler, kinderlakh, mit groys kheyshek

Itst iz ayer tsayt

Ver fun aykh es pedlt beser

Der vet zayn “Ol-rayt”

On this island called Cuba

The sun burns so hot

Peddlers go with their bundles

Soaked in sweat

Forget Europe with America

You’re in Cuba now

You must begin from the beginning, poor things,

Komets-Alef: “O”

When you are children, so you peddle

Two, three, four years

Then, with God’s help, you’ll be balebatim

With your own store

So peddle, children, with passion

Now is your time

He who peddles best

Will be “all right.”

Alongside this tongue-in-cheek piece, the Yiddish newspaper also urged its readers to “become Cubanized” and to “love their adopted land.” This tension was illustrative of Eastern European Jewish immigrants’ heavily ironic and often ambivalent attitude toward Cuba, their new (and often temporary) home.

Cuba’s history as a place of refuge for Eastern European Yiddish-speaking migrants between the World Wars is part of a broader and more complex history of migration to and within the Americas that complicates the US’s exceptionalist myths about immigration and national identity. Americans rarely think of Cuba as another “nation of immigrants,” but that is precisely what has animated Cuban literature and culture from its beginnings. It led Fernando Ortiz, a Cuban intellectual and sociologist, to coin the term “transculturation” in 1940 to describe the unique and ongoing interchange and transformation of immigrant cultures that he argued characterized Cuban life.

Historian Robert Levine likewise describes the multiracial, multiethnic atmosphere of post-World War I Cuba as unique, as both Sephardic and Eastern European Jewish immigrants competed with immigrants from Spain, Haiti, Jamaica—and even China—for jobs in a strained economy. The Yiddish-speaking population was especially mobile, with many only staying for a year or so until departing for other destinations, primarily the United States, and sometimes Mexico. Margalit Bejarano observes that “Cuba did not extend a warm welcome to its transit passengers.” She describes the culture shock for Yiddish speaking immigrants (“the language was strange, the heat was unbearable”), and their poverty. Many did not have the thirty dollars required by the Cuban government to enter the country, and so were detained in the Tiscornia Camp (Cuba’s Ellis Island). Many could not find jobs during the economic crises of the 1920s, and, unable to afford even the cheapest rents, slept in the parks.

Nevertheless, even as Yiddish-speaking immigrants awaited coveted visas, they established a Yidishe kulturgrupe in the 1920s, holding debates, lectures, literary salons, Yiddish theatre performances, and eventually a school. In 1927, the organization, now renamed the Centro Israelita, began to publish Oyfgang, which was joined in 1932 by Havaner lebn (later also called La Vida Habanera), which was co-edited by Oskar Pinis (also known as Asher Penn) and Eliezer Aronowsky. The two editors formed the nucleus of a group of writers who dubbed themselves Yung Kuba, a title reminiscent of the avant-garde Yiddish poetic movements of New York (Di yunge) and Poland-Lithuania (Yung Vilne). Asher Tshutshinsky, a member of Yung Kuba, later termed their collective voice a “nusekh Kuba”: the product of the “mix of Spanish-European and African cultures,” shaped by the “tropical climate, endless summer and atmosphere of freedom,” in contrast to the cold, poverty, and terror of Eastern Europe. Alan Astro describes the literary production of these Cuban-Yiddish writers as a Judeo-Afro-Cuban syncretism, exemplified by the stories of Avrom Yosef Dubelman and Pinkhas Berniker, which often described encounters between Jewish peddlers and merchants and the Afro-Cubans of the interior.

Issue of Havaner lebn. In the box on the lower left hand side is an ad for the Spanish translation of Pinis’s Hatuey.

Despite their identifications with Cuba, many of these Yiddish writers did not remain long, including Oskar Pinis. He arrived in Cuba in 1924, published his book-length epic poem Hatuey (1931) and a book of stories titled Der goldener fontan (The Golden Fountain, 1934) in Havana, and then immigrated to the US in 1935, taking the name Ascher Penn. And yet, Pinis left an indelible mark upon Cuban culture with Hatuey, which was quickly translated into Spanish and widely circulated. Pinis’s translator, Andres de Piedra-Bueno, a Cuban-born, non-Jewish poet and scholar, translated both Pinis’s Hatuey and Aronowsky’s Maceo, two important epic poems published in the 1930s which featured extremely popular indigenous and Afro-Cuban revolutionary subjects. Aronowsky, in turn, translated a number of Piedra-Bueno’s poems from Spanish into Yiddish, which Piedra-Bueno proudly included in his Obras Completas in 1939, insisting upon the “Cubanness” of Pinis, Aronowsky, and their fellow Yiddish writers.

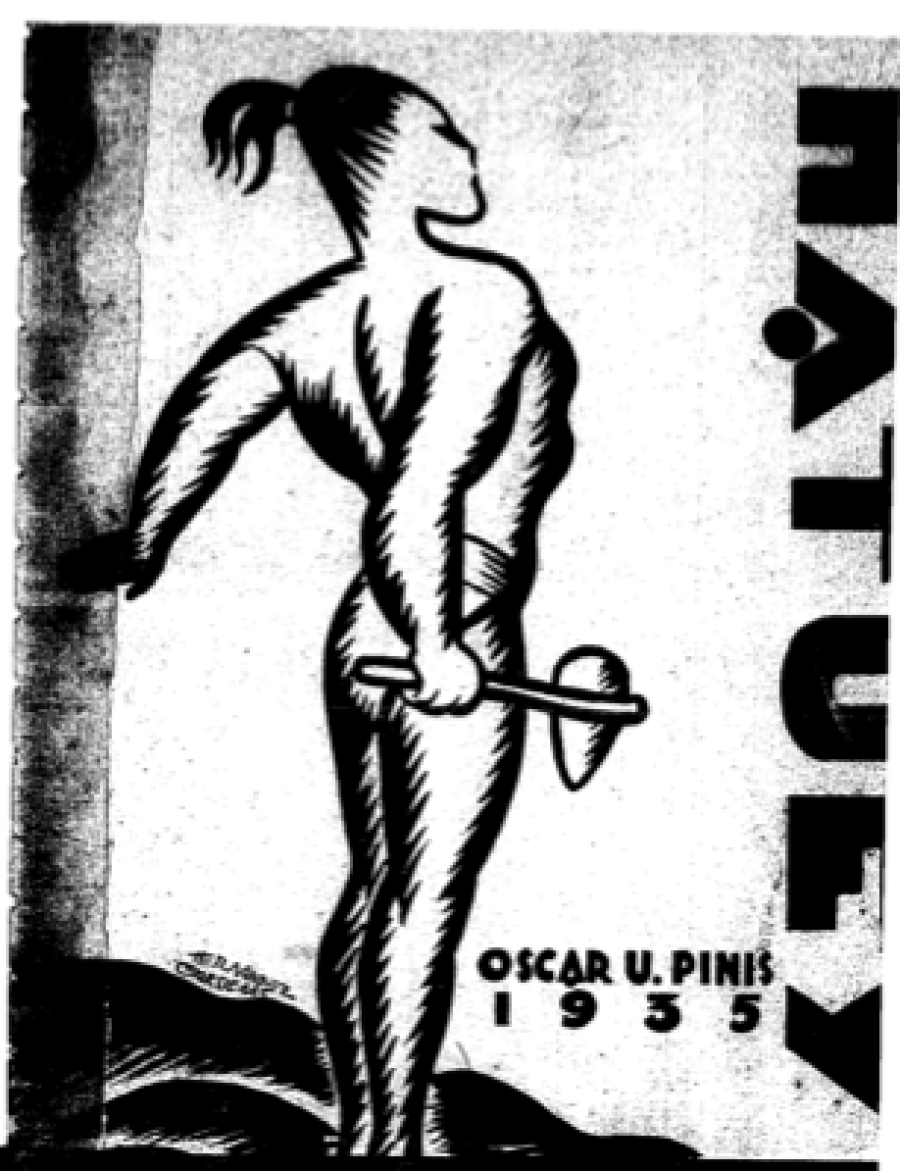

Title page for Pinis’s 1935 Spanish-language edition of Hatuey.

Were these new Yiddish-speaking arrivals immigrants or refugees? Were they ready to make Cuba their home or did they consider it a temporary stopping place on their way to the United States? Were they instruments in the efforts of the ruling elite to “whiten” Cuba after the First World War, or were they identified with other undesirable foreigners like those from Haiti and Jamaica, in the increasingly xenophobic and racist atmosphere of the 1930s? All of these characterizations emerge in discussions of this period and this community. In writing a Yiddish version of Hatuey in the early 1930s that developed a discourse of Jewish indigenismo, Pinis translated and revived important nationalist revolutionary tropes as a way of speaking to Cuba’s political and racial struggles in his present. Thus he participated in Cuba’s continuing effort, three decades after independence, to define the racial and cultural terms of its national character.

El Indio Hatuey first emerged in the writing of sixteenth-century priest and reformer Bartolomé de las Casas. Other early accounts of Hatuey’s rebellion and martyrdom followed, with similar outlines. In the early 1500s, Hatuey, a Taíno leader from Hispañola (today’s Dominican Republic and Haiti), set sail to Cuba with 400 followers ahead of Diego Velásquez, to warn them of impending Spanish invasion. Most Hatuey narratives feature his famous speech to the Indians of Cuba denouncing the Spaniards’ rapacious and violent desire for gold. In many versions Hatuey is unsuccessful in persuading others to join him; he then wages a guerrilla war against the Spanish with a very few followers. Captured and sentenced to burning at the stake (in many versions, betrayed by one of his own), Hatuey makes his second famous speech. Offered the choice of baptism by a priest so that he can go to heaven, Hatuey asks if there are other Christian Spaniards in heaven. Assured there are, he announces that he would rather go to hell.

It was José Martí, the Cuban nationalist and revolutionary in the later-nineteenth century, who identified the struggle against Spain for independence with Hatuey’s rebellion. All Cuban nationalists, in Marti’s formulation, were therefore Indians. Francisco Sellén, a Cuban intellectual and revolutionary exiled to the United States in the late-nineteenth century for his anti-Spanish activities, wrote his poetic drama, Hatuey in 1891, intending his play to be the “first national drama of Cuba.” Bonifacio Byrne, another exiled revolutionary and Cuban poet, wrote poems about Hatuey, Macéo, Céspedes, and Martí, all heroes of the revolution. In the Cuban fight for independence there was even an Indian regiment that was named the Hatuey Regiment.

Oskar Pinis.

But in the 1920’s and 1930’s, Hatuey’s meanings shifted. That period in Cuba saw the development of Afro-Cubanismo, a powerful arts movement that sought to affirm the African foundations of Cuban culture. The most aggressively avant-garde publication of the Minoristas (a group of artists and intellectuals who promoted the new Afro-Cuban cultural nationalism), first published in 1927, was called Atuei. Invoking Hatuey could thus gesture towards revolutionary, nationalist, and Afro-Cuban modernist mythologies, thus illustrating both his ubiquity and his malleability as a signifier.

In 1927 and 1928, a writer named Yaakov Shponka serialized biographies of Hatuey, Maceo, and Martí in Oyfgang, articles explicitly framed to educate new arrivals about Cuban history. Shponka called Hatuey “the first Cuban freedom-fighter,” as well as the first Cuban victim of the Inquisition, a fate that would have resonated with Yiddish readers and fellow writers, who often addressed crypto-Jewish themes in their fictions.

Pinis’s Hatuey follows the general contours of popular Hatuey legend, but is reframed within the poet’s own narrative of migration and adoption:

Hatuey un di zun—iz ot do a farglaykh. Beyde ineynem balaykhtn zey dem mentshlikhn veg in kuba. Un shteyendik af ot dem kubaner zunikn veg, af der erd, vos hot azoy breyt mikh ufgenumen un vos iz in mayn yugnt mayn tsveytn heym gevorn, trog ikh tsu mayn baytrog-dos gezang tsu Hatueyen.

Hatuey y el sol son la misma cosa en Cuba. Los dos alumbran el camino humano. Y yo, en este sendero solar, en la tierra que. Me ha abierto su corazón y que ya es mi segunda patria, ofrezco este homenaje: el poema de Hatuey.

Hatuey and the sun: they are the same here. Both illuminate the human way in Cuba. Standing here on this bright Cuban path, in this land that has opened its heart to me and became in my youth my second home, I bring my gift—this song of Hatuey.

Pinis’s Hatuey has a vision of the freedom fighters who will succeed him— this is a national hero self-conscious of his legacy: “Er veyst, az es veln nokh fray zayn di erdn/ vayl nit er iz der letster vos vil es zayn fray” (“He knows that the earth will be free, that he is not the last to desire freedom”). In the Spanish translation, Hatuey’s martyrdom is even more explicit: Hatuey “sabe que el sacrificio de su vida no sera/ el último que se ofrezca/por amar la libertad!” (Hatuey “knows that the sacrifice of his life will not be the last offered for the love of liberty!”). Pinis’s Hatuey concludes with a glossary of Native terms—like areito, cacique, and yucca, used in the Yiddish text. Foreign terms to Yiddish are not glossed in the Spanish translation—thus reifying the “translation sensibility” that animates the poem, marking its distance from its subject even as its author claims identification and intimacy.

De Piedra-Bueno’s 1935 Spanish translation explicitly argues for the sympathies between Pinis, Cuba, and Hatuey. Piedra-Bueno’s translation included a biographical note reprinted from a 1933 survey of Cuban literature that included an entry on Pinis:

Su primer libro fué una exquisita e interesante aportación a la poesía épica cubana, a través de un ardiente temperamento hebreo, que sintió vibrar en su alma el espíritu rebelde del glorioso indio Hatuey y se extremeció ante la crueldad hispana de la horrible hoguera. Desde los primeros sorbos de historia cubana, Pinis empezó por cantar al Hatuey enemigo de los opresores, del oro, Dios de los blancos.

[Pinis’s Hatuey] was an exquisite and fascinating contribution to Cuban epic poetry, by way of an ardent Hebrew temperament, that felt vibrating in its soul the rebellious spirit of the glorious Indian Hatuey, and shuddered before the cruel, terrible bonfire of the Spanish. From his first tastes of Cuban history, Pinis began to sing of Hatuey, enemy of the oppressors and of gold, the god of the whites.

Both the Hebrew and Indian “spirits” are passionate, rebellious, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist—a subtle but politicized recasting of Pinis’s and his attraction to Hatuey’s rebellion in the era of Machado’s regime. From his manipulated reelection in 1928 through his ouster in 1933, Machado maintained martial law and increasingly targeted Jewish organizations and individuals, primarily labor organizers and Communists. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported in 1932, for instance, that Eliezer Aronowsky and three other Cuban Jews, including another newspaper editor, had been arrested “on charges of expressing opposition to the present government.” Piedra-Bueno’s 1935 translation can also be read as a response to the tumult of 1934, which had just seen a popular and progressive uprising against Machado, a short-lived reformist government, and the installation of the first Batista-controlled government: a “dictatorship,” Levine terms it, “in democratic clothing.”

Contemporary interpreters identify an additional subtext for Pinis’s Hatuey, about which both Piedra-Bueno and Pinis himself were silent. As Alan Astro writes, in addition to sympathizing with victims of the Inquisition now that they found themselves living in its former territories, Yiddish speaking immigrants, many involved in leftist causes in their countries of origin, had also fled pogroms and state-fomented violence. Where Cuban readers of the 1930s might have easily seen parallels between the violence and persecutions of the Inquisition, the modern struggle for liberation from Spain, and the repressions of Machado’s regime (not to mention the struggle against the Fascists in Spain), Yiddish readers in particular might have additionally identified the violent anti-semitism of the Inquisition with that of twentieth-century Eastern Europe.

In 1927, Pinis authored a three-part narrative in Oyfgang, “In a finsterer tsayt (tsum shvartsn ondeynkung fun Petlyuren)” (In a dark time: the black legacy of Petliura), that describes a pogrom in his town that he and a group of Jewish families survive by hiding in a Christian neighbor’s barn. They hide for hours, listening to gunshots and screams outside. When night falls, the neighbor decides he cannot hide them anymore. The tale ends as the desperate families leave the barn for an unknown fate. Pinis was only eighteen or nineteen years old when he published the piece; he had been in Cuba for three years.

In Hatuey’s current iteration as a multilingual opera for a contemporary American and Cuban audience, Pinis’s childhood trauma of witnessing and surviving a pogrom has emerged as an explicit theme, as has the violence of Machado’s regime. Frank London and Elise Thoron’s opera is set in a Havana nightclub in 1931, where young Ukrainian poet and refugee, Oscar falls in love with Tinima, a singer of Taíno descent, and is drawn into her revolutionary activities against the Machado regime. All the while Oscar is writing his poem, Hatuey, telling the story of Cuba’s first indigenous freedom fighter, who dies at the stake resisting the Spanish in 1511. The two stories intertwine and inform each other, as characters shift in time and place from Havana club in 1931, to the world of Oscar’s poem in Maisi, 1511, where his hero Hatuey encounters Velasquez and the Spanish.

Opening passage and dedication of Hatuey.

Opening passage and dedication of Hatuey.

In a striking example of what we might term Judeo-Afro-Cuban indigenismo, the opera, like the work of the Cuban-Yiddish writers who serve as its inspiration, imbricates languages, identities, and histories—Spanish conquest, the Inquisition, slavery, Ukrainian pogroms, Machado’s dictatorship—through the interpolation of a new frame that features an intercultural, interracial romance. London’s score likewise fuses Afro-Cuban, avant-garde jazz and klezmer genres. Indeed, the opera Hatuey: Memory of Fire has been, and continues to be, in an ongoing and dynamic state of translation. Multiple translators, many proficient in both Yiddish and Spanish, have worked on the libretto as it has moved between and among English, Yiddish, Spanish, and Taíno, reflected in London’s “operatic jazzy-klezmery-cubano fusion.”

The curiosity of a Cuban-Yiddish poem making its way back to Havana as an opera has inspired a great deal of coverage in the American, American-Jewish, and Cuban press, the former usually foregrounding Pinis as a Ukrainian Jewish refugee who fled to Cuba and adopted the literary themes of his new country, and the latter seeing the opera as an important symbol of contemporary Cuban-US artistic collaboration in the age of Obama. The meanings of Hatuey have thus undergone further transformations through these acts of cultural translation and exchange: from revolution to nationhood to commercial appropriation (these days, most know Hatuey as the name of a beer—a fact that plays an important narrative role in the opera Hatuey); from avant-gardist Afro-Cuban modernism to linguistic extinction and revival, from the possibility of a new homeland and new future to a reminder of a traumatic and violent past, from a harbinger of renewed diplomatic relations between two estranged nations, to what is now an act of resistance and defiance against a new American administration that seems to be turning its back to the rest of the world.

The journey of Hatuey in particular, from Spanish to Yiddish to Spanish; from Spanish to English; and now again from Spanish into Yiddish, Spanish, English, and Taíno, embodies the multidirectional relationships Yiddish in the Americas could and did develop with other languages. Yiddish immigrant audiences in the Americas engaged with national myths—including and perhaps especially those that produced racialized understandings of people and nationhood—in and through translation. The continuing afterlife of Penn’s Hatuey demonstrates to us how Yiddish literary texts circulated and continue to circulate amongst non-Yiddish readers in the Americas through translation and thus continue to engage with, challenge, and transform national narratives.

All translations are my own unless otherwise indicated.

Rear more about Hatuey here.