Esther Shechter

Audiences Are Idiots

Faith Jones

One of the hardest problems in theatre studies is understanding audiences response. Nobody goes around collecting the opinions of everyday theatre-goers to preserve for posterity. Theatrical memoirs can give us some hints of audience reactions, for example by noting fan groups or long runs of certain shows, but the notorious ego intrusions in actor-authored books render them unreliable. I’m sure it never occurred to any Yiddish actor that the opinions of the audience might be of interest: they called theatre-goers Moyshe (Joe Blow) or even Moyshe tukhes (the same thing with a mild obscenity appended). Oylem iz a goylem, goes the saying: audiences are idiots.

Every now and then you find a clue where you weren’t looking for one. I found one in Winnipeg.

Winnipeg is a mid-size city in the middle of the Canadian prairie—approximately in the middle of the continent, a little more than 200 miles north of Fargo, North Dakota. There have never been more than 19,000 Jews in Winnipeg, but in Yiddish terms Winnipeg has always (and continues to) punch above its weight. The active North End community was in contact with international cultural figures and kept itself up to date on developments in the Yiddish world.

Starting in the 1910s, this community could experience Yiddish theatre. Once a year the amateur Dramatic Union would produce a play for a two- or three-night run. At the same time, traveling professional troupes came through on a regular basis. In their heyday perhaps as many as three companies a year would cycle through Winnipeg, each one stopping for a week to produce one high art drama and two or three crowd-pleasers. These were a mix of comedies and shund, or trashy, tear jerkers—and in later years, vaudeville sketch performances.

Since there was no professional Yiddish theatre permanently established in the city, there was no theatre critic at the Yiddish paper, Dos Yidishe vort (The Jewish Word). Even the professional theatres that appeared sporadically on tour didn’t get a proper review in the paper. The best they could get were toadying announcements urging everyone to go see the great theatre artists in the classic work of art, etc., heaping daytshmerish praise on all performers and plays equally. Daytshmerish was a stylized way of using German words and phrasing that was thought to lend class to lowly Yiddish, rather in the way Miss Piggy invokes a continental refinement by referring to herself as moi.

Daytshmerish praise is heaped upon Gordin’s “The Russian Jew in America,” starring Isidore Meltser.

While researching something completely different, I found an incredible example of audience reaction in a memoir by Esther Shechter, a Winnipeg resident and Yiddish language and culture activist. Shechter lived in Winnipeg from 1905 until her death in 1953. She was active in virtually every Yiddish organization in the North End. She worked for the Yiddish bookstore, sold print jobs for the Yiddish newspaper, sat on the Peretz Shule’s muter fareyn (the “mother’s union” that did most of the work of guiding and running the school). She took part in a Yiddish reading group, raised money for Pioneer Women, and attended every lecture, performance, or literary reading in Yiddish or about Yiddish culture. She was extremely poor for almost all of her Winnipeg life, but she was well-educated and read voraciously. Her particular passion was politics and current events, and she had subscriptions to as many newspapers as she could afford.

In 1951, she published her memoir, and, oddly, included in this book her many letters to the editor of Dos Yidishe vort. A few of them are about touring professional Yiddish theatre. Since Shechter was not a professional writer or artist, and was in fact a bit clueless about art, we have in these brief letters the perfect everyday-person response to the Yiddish theatre.

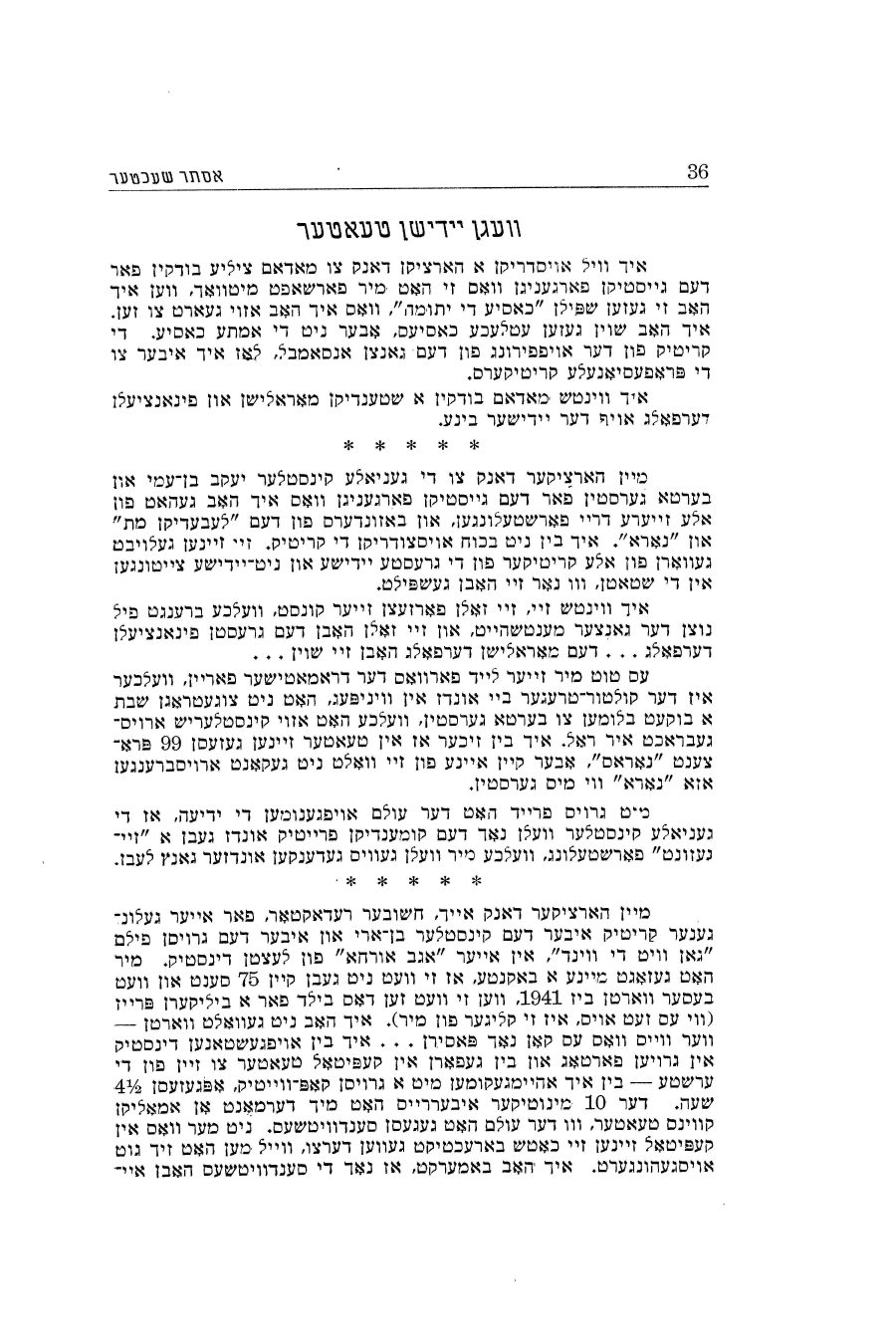

She doesn’t date the letters to the editor she includes in her book, but here is one I believe comes from 1939:

My heartfelt thanks to the brilliant artists Jacob Ben-Ami and Berta Gersten for the spiritual pleasure that I took in all three of their performances, and particularly in the “Living Corpse” and “Nora.” I do not have the power to express myself like a reviewer; they have been praised by all critics from the largest Jewish and non-Jewish newspapers in the States, wherever they have appeared.

I hope they will continue their art, which is of great use to all of humanity, and wish them the best financial success. Artistic success is already theirs.

It is very painful to me that the Dramatic Union, which is the culture bearer for us here in Winnipeg, did not give a bouquet to Berta Gersten on Saturday, when she had so artistically performed her role. I am sure that in the theatre sat 99 percent “Noras,” but none of them would be able to perform “Nora” as Mrs. Gersten did.

The audience received the news that these brilliant artists will give us a farewell performance on Friday with great joy. We will certainly remember it our entire lives.

Shechter’s letter to the editor, reproduced in her memoirs in 1951.

There are so many interesting things packed into this short letter. First, we can see that Yiddish theatre is already past its prime. In an earlier era, the touring company that came to Winnipeg would frequently star someone who could claim to have appeared in Warsaw, New York, or Buenos Aires—but in those places, would have appeared in a bit part, or even a walk-on, in the company of a Thomashefsky or a Kalich. In Winnipeg, touring companies normally reflected the glory of the big city productions indirectly, through a six-degrees-of-separation kind of stardom. But in 1939, stars like Ben-Ami and Gertsen saw fit to make the trek to Winnipeg, or, presumably, anywhere there were enough Yiddish-speaking Jews to fill a theatre.

The fact that major actors were finally coming to Winnipeg might help account for the star-struck tone of Shechter’s letter. Shechter’s authorial persona throughout her book is crusty and umimpressed. This letter is one of the few places she allows herself to be truly awed in the presence of greatness. She maintains her typical crustiness only in her disparagement of the local klal-tuers, the community bigshots, who messed up the flowers.

While the amateur Dramatic Union generally performed plays by major Yiddish authors, the professional theatres mixed in translations of European classics, with an emphasis on the Russians. The plays Shechter comments on are, of course, by Tolstoy and Ibsen. Shechter was sufficiently invested in knowledge and education that she probably only attended the high-art productions, and gave the light-weight material a miss.

It’s hard to imagine a letter like this appearing in a Yiddish newspaper in New York, or any city where professional critics were available to to tell people what to think. In fact, Shechter specifically defines her reaction in contrast to that of professional critics. She makes a public intervention on behalf of the Yiddish theatre and its artists in a way that would not be considered useful in a larger centre.

Esther Shechter

At least when it came to Yiddish theatre Shechter acknowledged that an aesthetic experience was the goal, even if she couldn’t articulate exactly what that meant. The same year that Shechter waxed poetic about Ben-Ami and Gersten, she also sent a letter to the paper about a very different kind of cultural event. The biggest movie that year was “Gone With the Wind.” Like many people, Shechter lined up to see the four-hour spectacle in a downtown theatre. Given her political affiliations and sympathies, I imagined she would grapple with the problematic material, which elevated slaveholders at the expense of African Americans, a group with whom North American Jews tended to feel a great deal of kinship. But nothing of the sort. She likewise had no comments on the performances, cinematography, costumes, or any other artistic aspect of the work in question.

So what does she discuss? Shechter’s “Gone With the Wind” letter is primarily concerned with her unpleasant physical experience of the movie. She notes that the music was too loud. More importantly, she is astonished that, at intermission, when the audience still has two hours of movie to get through, there is nothing available to eat at the theatre concession.

Possibly a lot of Yiddish theatre attendees were like Shechter. For them, the theatre was not so much an aesthetic experience as a collective one. The rather extraordinary intellectual striving of people like Shechter—an impoverished immigrant with a huge attachment to both Jewish and non-Jewish thought—shines a rather different light on the matter than the either the professional critics or the actor memoirs do. Shechter reports being transported by the artists’ work in the play, but does not describe what about the performances made it memorable or what the actors did to evoke an emotional response. Her praise could refer to any production of any play, so nebulous are her comments. Yet it was important to her to register these vague thoughts in the public sphere, and to impress on her fellow Winnipeggers the importance of attending and appreciating Yiddish theatre.

What we can learn from Esther Shechter is that audiences are not necessarily idiots—Shechter certainly wasn’t one—but that they may have gone to Yiddish theatre for reasons that were far from what the actors or playwrights intended. They went to be grounded in Yiddish culture, and to be part of the trans-national Jewish body politic; they went to hear the Yiddish word and to feel part of a community. Whether or not the actors believed themselves superior to the audiences, especially in smaller Jewish centers, the fact is that theatre served as a support and comfort to far-flung Yiddish life.