A brothel known by the name "El Paraíso" (paradise) was located in this building in the city of Rosario.

Adapting God of Vengeance in Buenos Aires: An Interview with Argentine Director Daniel Teveles

C. Tova Markenson, David Mazower

There have been multiple productions of Sholem Asch’s canonical drama God of Vengeance in recent years, in the original Yiddish and in translation. Within the past five years, the play has also featured in one new work (Indecent, written by Paula Vogel, produced on Broadway in 2017) and served as the basis of two creative reinterpretations: the 2018 Cameri Theater (Tel Aviv) production, El Nekamot, directed by Itay Tiran; and El Dogma, the creation of Argentine director Daniel Teveles. These three intensely theatrical productions remained faithful to elements of Asch’s play, but went beyond it, mining different aspects of the original while also holding up a mirror to issues that remain powerfully resonant—discrimination and abuse, censorship, nativism, and anti-immigrant rhetoric. Each production also highlighted aspects of Jewish history that mainstream narratives have tended to suppress. This is especially the case with El Dogma. The story of Argentina’s powerful immigrant anarchist and radical traditions, its brutal state-directed pogrom of 1919, as well as its specific Jewish history of organized prostitution—all of this is almost entirely absent from the contemporary Jewish imagination. Daniel Teveles weaves this hidden history into the story of God of Vengeance to create a thrilling new piece of theatre. In this interview with DYTP contributing member C. Tova Markenson, Teveles gives us an insight into his creative process.

- David Mazower

C. Tova Markenson: In an interview with Red Teatral, you mentioned that the idea for El Dogma came from your own childhood memories. What do you remember about going to the Yiddish theatre?

Daniel Teveles: Music has had a very strong influence on my awareness. The melodies sung in sweet Yiddish that I listened to as a child, the 78 records that my “zayde Usher” played on his “Winco” with lyrics that I half-understood, even when they made my hair stand on end when I listened to them, they brought me to the Yiddish theatre.

These sacred “temples” such as theatre auditoria of the Soleil, Excelsior, Mitre or IFT, among others in Buenos Aires, where I went to listen to those texts spoken in that language, bring me nostalgia and joy at the same time. There were only elderly spectators which gave the impression that this was not good for the future of this theatre. Except for the last theatre (IFT), today all of them have vanished. The IFT theatre which continues today is open to other areas of dramatic art, it was the space to see theatre from texts in Yiddish—beautiful theatre. In the former Mitre theatre, in which there were ground-floor boxes, today there is a Chinese supermarket, another language. It is sad for me to walk by there. It is as if the ghosts resist leaving; the theatre leaves a special energy in the air.

Today I channel that empty feeling in the theatre that I make. Upon entering an auditorium, it is as if returning to life, it is purely experiential, it is my youth.

The smell—each theatre smells differently. I can still smell the mothballs from the coats of the women and the mix of spray from their updos from the hair salon, indestructible, to the wind and the waves, and the men with ties or bow ties from their recently pressed suits. It was a party!

My childhood games were purely theatre, inventing words in Yiddish; the wire for hanging the clothing from my home served as the curtain; the furniture was the set, the lanterns, the lights. What chaos. There telling stories, in a musical duo with my brother, with a cane and galley behind this beautiful imaginary red curtain, gesticulating and emulating Ben Zion Witler or Pesach Burstein.

The director of the orchestra, Don Simón Tenovsky, my friend…his baton started to move with vigor and the first beats of the overture began to sound…the magic…the rise of the curtain. I learned to love or hate these people, through the actors who put on their bodies, in a symbiotic agreement with the spectator. They were historic, beautiful vaudevilles, the closest thing in spirit in today’s theatre are probably “musicals.” These fictional histories that I somewhat understood, and that my grandparents came to explain to me, were formative for my interest in the theatre. Nostalgia was a great stimulus for sealing my desires and making me who I am today.

El Dogma, the illusion of Paradise, my work, is the “closest” to this theatre. I wanted that for my actors of today, that they would speak as if they were the most talented performers on the Yiddish stage.

CTM: How do you describe yourself as a director? And how would you compare Dogma to your previous projects?

DT: The plays that I direct, write, design, etc. come from imaginary games. They are images that ignite, while I read or sleep or listen to music. I like to participate in all aspects of each project. I am obsessive. The plays are like children. One grows with them. I mature and learn from the mistakes. The public perceives the quality, and this is what is important. I look for texts that I can give a different vision to, one that is personal, original, and touches the audience.

The phase before a creative act is fantastic, because it requires research and a lot of it. This is the interesting phase of any theatrical proposition and that which I wish to express. The opposing, conflicting forces of the characters ought to be intense. Jewish humanism is behind my works, without them being specifically Jewish. El Banco (Die Judenbank) was a great work of research and was a different look at the Holocaust; the person who was discriminated against was not Jewish, they were not Jews and this was what was original for a topic that is so well-travelled.

La luz de un Cigarrillo (The Light of a Cigarette), as in El Dogma, addresses themes relating to immigration, for example: alienation and adapting to new cultures, different ways of life, and about adaptation. Identity in conflict, in all of its aspects, is the most precious material that we have as humans. From there we can write infinite histories.

Casta Diva is another work that I wrote, about María Callas in her twilight; with good critiques, talking about everything, from the end of life and her acceptance of it. Topics that I am concerned about, both me and my characters. It was an intense dialogue with her alter-ego. Very surrealist.

La Luz de un Cigarrillo also had surrealist scenes. Images in action that accelerated the text and another ending. Characters invented during the recreation of the self, that did not respond to the original work and the good wishes of the writer, that came to the premiere and admitted them.

In El Dogma there also are characters and new scenes that are not in Asch’s text and this gives a certain actuality and local resonance to what is offered. All of my performances have music that aligns with the story that each play tells. They are very musical and this comes from the theatre from my childhood.

When I read God of Vengeance, after it was translated from Yiddish, it had an immediate impact on me. I felt a voice in my head saying that this was the work that I should bring about, the images were immediately appearing, as was how to perform them, the necessary changes and what was needed to recreate the questions in the text to connect them with the present, through another perspective. As with in Luz de un Cigarrillo, I needed to work through the intensity of the characters in Spanish first, the action, without memorization, and slowly incorporate the Yiddish with a coach.

Theatre is fiction, but it should have truth in it. I like challenges, there are always risks in that which is different. It is like working on the edge of a knife. It is worth the struggle, even when it is arduous work. I take the characters to their extreme limits, to try to shock the spectator.

In El Dogma the first scenes are spoken in Yiddish (with subtitles), a language that the parents hope to use so that their children do not understand. This play speaks to the problems of a Jewish family. But these issues take place in other areas, be they religious or political. People who speak of these wounds even though they do not scar, those who live in tension convicted to cancel wither desires, family secrets that escape into the light, those of hypocrisy, of a double standard. Humor needs to be present, to “ease” the spectators, loosen them and bring them to the place that they are able to go.

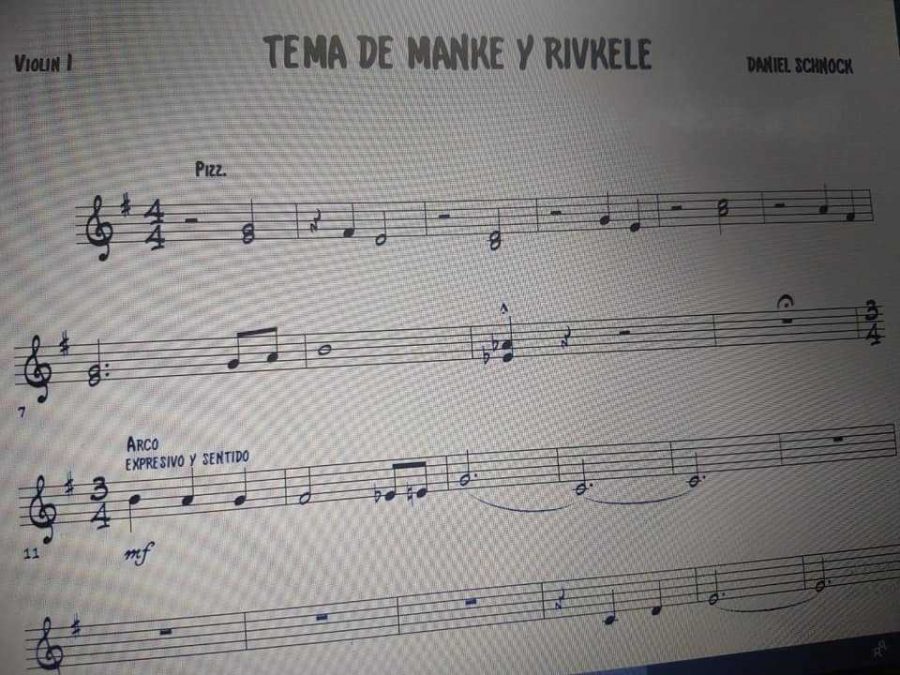

Theme music for the characters Manke and Rivkele.

CTM: What was your process of developing the script?

DT: When my father was angry he would say “those people” who go to “shul” and leave afterwards and conduct commercial scams or other great transgressions, the person condemned in this behavior was contradictory and hypocritical. That left an impression on me. Human contradiction. In El Dogma the unquestionable is questioned. Exposing the corruption, the easy money, and the lack of respect for the desires of the children, the double standard and hypocrisy. There are many dogmas. To obey dogma is humanly impossible and this is what makes it so attractive.

I worked for several years at the Jewish Genealogical Association of Argentina. I had read a lot about a local Jewish mafia organization, the Zwi Migdal and its beginnings. No one could have a business like that, and such a visible one, without there being collusion with power. The impure Jews, as they were then called, were the visible face. The Jewish mafia, comprised of people and so tied to this conduct, to the ethical nature of religion. I found this contradiction very interesting. I looked for a work that could address this theme. I knew of this writer, a Polish genius and visionary for his time, Sholem Asch, candidate for the Nobel prize.

He was the author “of theatre in Yiddish” par excellence, and I knew of his work through my grandparents and through my reading of theatre. Over three years ago, I went to the local IWO (Jewish Research Institute) to look for one of his texts. I had known about his polemical work from his biographies, and it was there that I found a Yiddish copy of Got fun nekome. Nejana Barad did the translation, because there was none yet in Spanish. And from there I started my work of recreating this monumental play. The play was produced in Yiddish in Argentina and without any censorship issues. From that came El Dogma, which is a series of hypotheses or undeniable principles, be they religious, political, familial, or social that frequently are taken on, the people drawn to fanaticism. They interfere with reason and passion. There is a hypocrisy of dogmatism, where there is a double standard in diverse environments and the self-deception, looking for freedom, paradise. God of Vengeance originally took place in Poland. But my version with new scenes and a great part of the history takes place in Buenos Aires, because it was in Argentina where prostitution in the hands of the Jewish mafia peaked as a phenomenon in itself. Here Jewish mafia institutions were given a mark of “quasi” legality, with an excellent administration, with numerous members, and everything that was required of a communal institution.

On the other hand the research, the books, and the archival material helped me to contextualize the scenes, where the slavery of the women under the power of traffickers and the situation of the factory workers from the metalworkers of the Vasena in Argentina during 1919, were comparable by the same miserable salaries. It was an environment where immigrants such as Simón Radowitzsky brought socialist ideas and the specter of anarchism to Buenos Aires. Many feared that these immigrants would install a “Petrograd” here in Argentina. This was a time when the bourgeoisie was on the rise. It was also an era during which immigrants were looking for redemption…paradise…One of the greatest difficulties for me was to construct an image of a pimp who was Polish, Jewish, Argentine, and religious.

To construct this character, I began with what I knew and was familiar with: the Zwi Migdal. I reread the many books that I had in my house and articles from the journal Toldot, a research journal that I participated in. At the same time I saw several films, including La Tierra Prometida by Andrzej Wajda, which is extremely interesting. All of the research helped me to define the characters and create the situations in the play.

CTM: What do you see as the most important differences between El Dogma and Got fun nekome?

DT: El Dogma starts with a philosophical question about fate and dogmatic religious fundamentalism…Is fate an act of subjugation? And this is a primary crux of the text. This is the central question, without disregarding other questions from the original. It starts with a character, a narrator, who is not in Asch’s text, who tells a story, a story that ends up being theirs, to the surprise of the spectator which perfectly concludes the story in a true finale. This person carries the conducting thread throughout the entire work. It begins in the year 1965 in Buenos Aires, with this story. God of Vengeance takes place in one single short time-frame and in Poland. Asch’s Yankl (Jacobo) is afraid of being punished by God, which humanizes him. In El Dogma it is the same. But the doubts are made greater in a scene of internal feeling of Jacobo (Yankl) in the third act, in his dialogue with God, he says, “I want to understand, not believe. Where are you, oh God?”

He becomes more distressed, and then becomes irate. We live in world where religious extremism and homophobic factions are growing in the Jewish community, and are unable to interpret or adapt to social change. This orthodoxy is homophobic and xenophobic and this is central to my perspective. Not all women were forced into prostitution by the Zwi Migdal; hunger was an important factor that united them. Inquiring even more into each one of their histories surely shows the different personalities and lives of each one. This is one vision of the different situations that each exploited woman came from; histories with a greater history.

In 1919, immigrants continued to arrive. [There were] strikes and social upheavals. There was a pogrom in Buenos Aires, with the death of almost 2,000 people. This is rarely talked about. The majority of people [who died] were Jewish. It was known as the Tragic Week. In El Dogma, especially in the scene with the beggar, there is an indication of the political and social conditions of the time as well as the death of the protagonist. In the suburb, a ghetto of local people, the Ruso (as Ashkenazi Jews were called) mixed curiously with the gringo. Those were years of antisemitism. Because the Jewish gringos and Italians brought with them socialist anarchist ideas that the local governments and landowners did not approve of, in addition to the known antisemitic myths. The unclean businesses were a way to encourage antisemitism. The scene in which Yankl negotiates with a corrupt mayor is based in reality.

Rivkele, the daughter of the pimp, is emotionally stronger than in Asch’s work. If she had the guts to be with a woman in an act of love, she should also be able to deal with a rebel allegation, more intense than her machista father who is part of the mafia. This gives reality and equilibrium to the proposal. She confronts her father, in a world where she reads a variety of books, her father only reads the Torah. Manke prompts her and she is made freer. Yankl suffers a lot. His accusation and his doubts about the existence of God enter into evidence with more intensity.

Rabbi Ellie is a caricature in this Argentine version, gives the play humor, plays with the audience, he is a kind of Shakespearean fool, astute, who knows Yankl very well. He is his colleague, looking for money, for his own community. He knows very well the origin of the money but is also a victim of the system. To win the heavens through achievement is a false consolation, an act of self-deception. Redemption, without making us in charge of our own evils and passions, is a central point in my offering. The finale is a moving sight for the spectator as a result of its poetry.

Behind the scenes: building the set of El Dogma.

Behind the scenes: building the set of El Dogma.

Behind the scenes: building the set of El Dogma.

Behind the scenes: building the set of El Dogma.

CTM: Is Dogma at all connected with the play El Dogma written by Argentine-Jewish playwright Samuel Eichelbaumm (1922) or Paula Vogel’s Indecent (which also adapts Got of Vengeance)?

I have not read Eichelbaum’s 1922 El Dogma, I didn’t even know it existed. I have read others: El Judío Aarón, Un Guapo de 900, and Pájardo de Barro. There is also Nadie la Conoció Nunca, which is a short text by Eichelbaumm on a related theme. It speaks of a women who was a prostitute during this period, immersed in an environment of high society and local antisemitism. He, like Asch, wrote about this controversial topic, being Jews, in a difficult era, where out of fear of antisemitism and shame, this was not spoken about.

I saw Indecent by Paula Vogel on the internet on a site for theatre on film. The work of Vogel provides a very local vision from a sociological and political point of view, which is a point of overlap for us.

El Dogma, like Indecent, intersperses scenes from God of Vengeance. My version is also local, because it locates the plot in its own ideal Argentine historical context.

The adaptation by Vogel is a “play within a play” and is presented in a musical format. The tango and the Polish tango from the era are presented and enrich the climate of the work of El Dogma. It has music that suits scenes and were created together with the text.

In general, both plays maintain the central conflict from the original play. El Dogma and Indecent have distinct visions with different conclusions, taking place in different societies and contexts. Both works question and ask what is moral and what is immoral, what does it mean to be pure.

CTM: What message do you hope that El Dogma leaves for its Argentine audiences?

The work is a great act of humanism and has several messages. It invites the use of reason. Argentines are passionate and sometimes this is not good for everything. Because it can turn one into being purely dogmatic and creates a social and political breach. El Dogma addresses many themes that are not unique to Argentina but are universal. To look at yourself in the mirror sometimes is a very good thing.