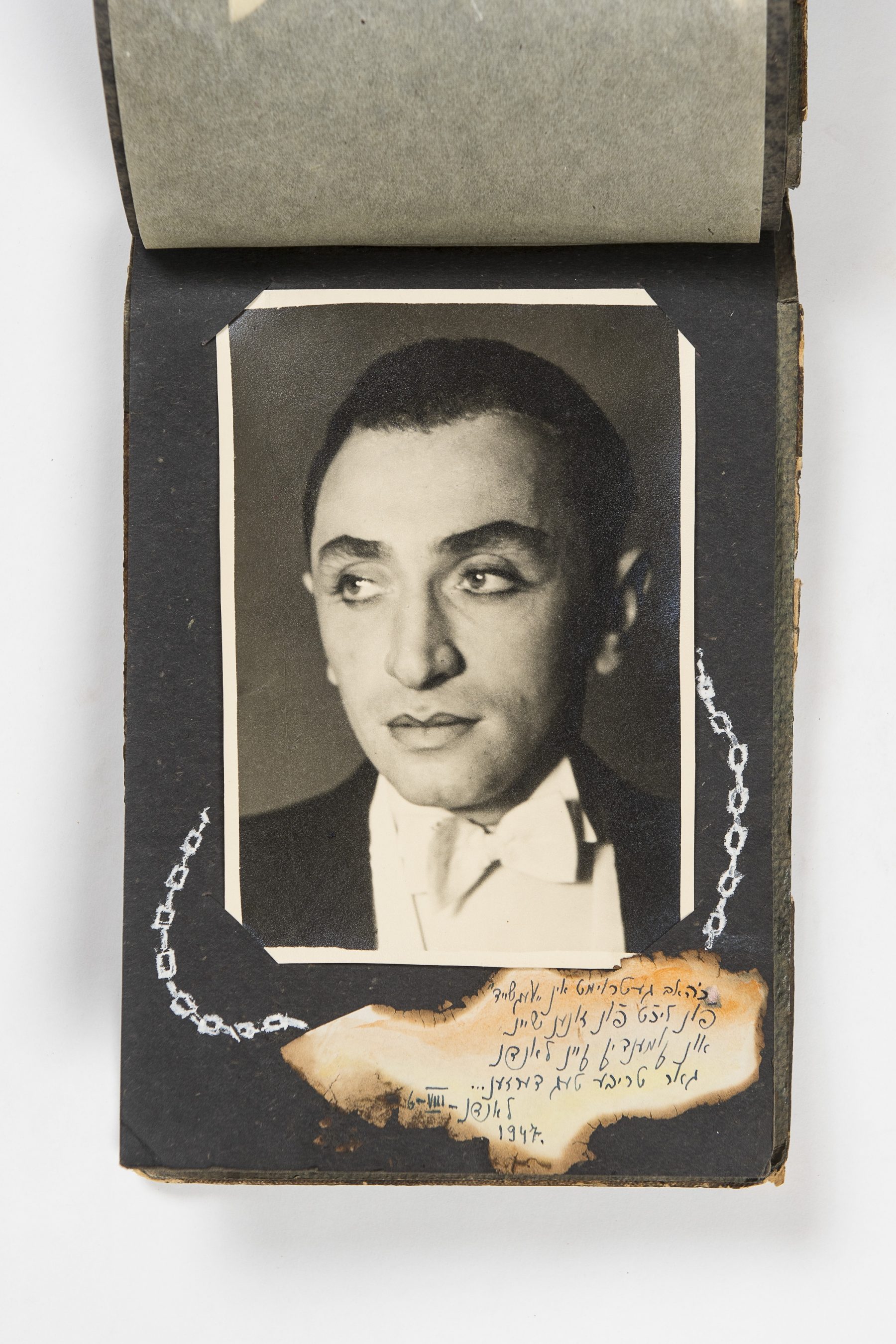

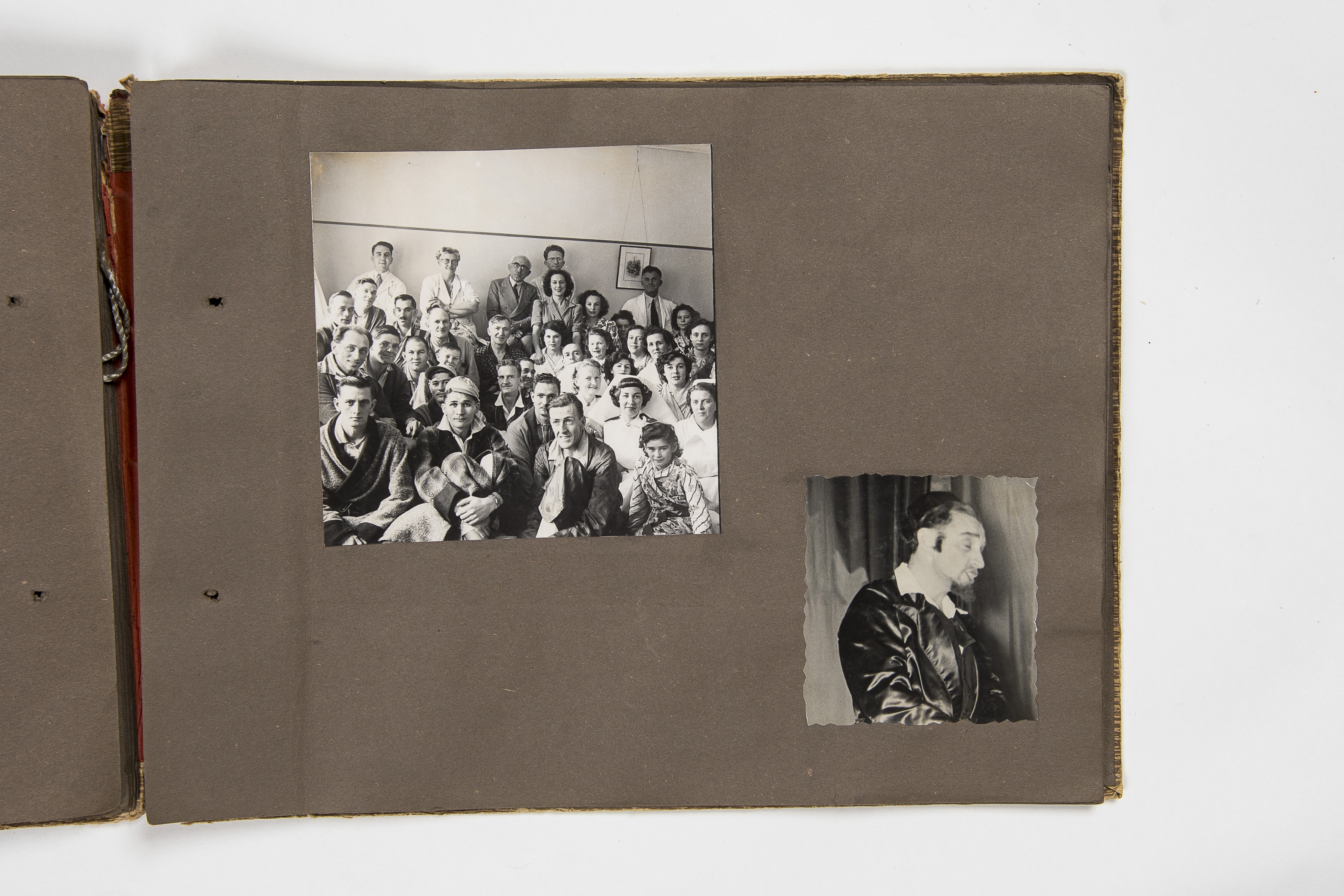

Final page from Harry Ariel’s scrapbook of his years in Vegscheid Lager DP Camp in Linz, Austria.

Zylbercweig’s Leksikon and Selfridges’ Rump Steak: In Memoriam Harry Ariel

David Mazower

I had heard so much about Harry Ariel, but there came a time when I began to wonder if he was a flesh-and-blood Yiddish actor or an elaborate theatrical joke. I had made two visits to the tiny flat in Whitechapel that he shared with his friend Bernard Mendelovitch, but on both occasions, Ariel was nowhere to be seen. His absence was noted matter-of-factly by Mendelovitch: “You might get to meet Harry,” he told me, “but don’t be surprised if you don’t.” This only deepened the air of mystery, as though Ariel had a sideline that entailed unpredictable absences—an emergency doctor perhaps, or a master criminal.

It was the summer of 1985. I was a young museum curator, curious about the history of Yiddish theatre in London. Mendelovitch was a retired Yiddish actor who had become my volunteer consultant and guide. I knew little about my chosen subject, but I had read enough to know that Ariel was a key witness, a living link between the Yiddish stage of pre-war Poland and post-war London. As I got to know Bernard better, he began to invite me round to their tiny council flat behind the London Hospital—through the backstreets, into a foul-smelling stairwell, up two flights of concrete stairs, then into an immaculate apartment where every available storage space was stuffed full of programs, stage photos and handwritten play scripts. But where was Harry? Gradually, the mystery evaporated. Ariel, it turned out, was pathologically shy and had stepped out of the flat to avoid meeting me.

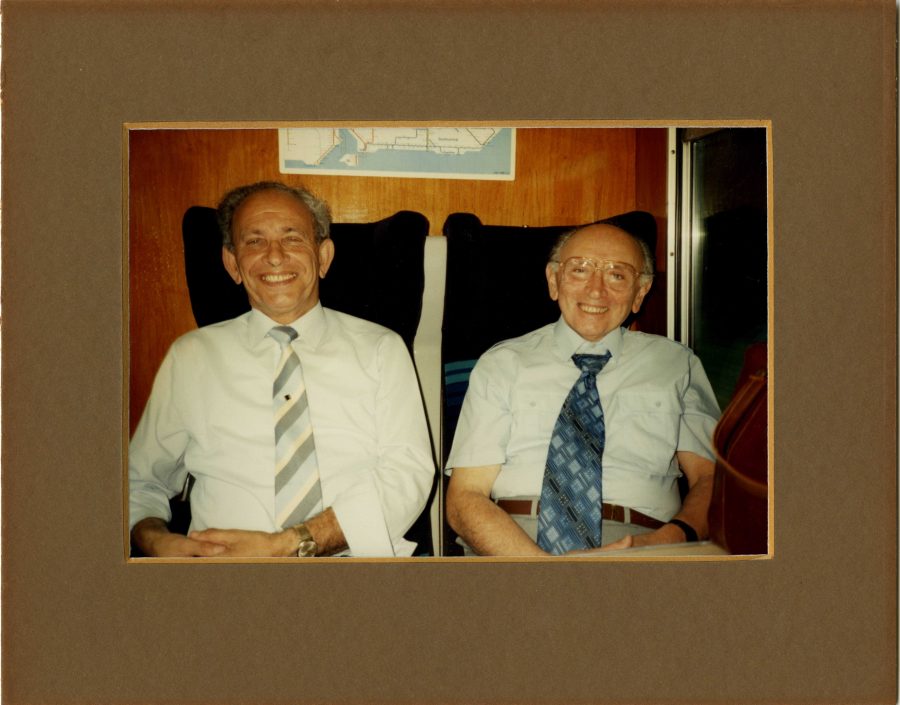

Harry Ariel (right) and Bernard Mendelovitch (left) on the train en route to a show at the Oxford Yiddish Institute, circa 1986.

Over time, Ariel’s shyness lessened, the invitations became more regular, and my friendship with both men deepened. I quickly grew to love my visits to “Philpot Strasse”—Bernard’s wry nickname for their narrow street, investing this dingy East End thoroughfare with a Noir-like Weimar glamor. Harry was the cook, typically greeting me wearing a large striped apron. He would retire to the pocket-sized kitchen to grill rump steak which he bought from Selfridges’ Food Hall on bus trips to the West End. The butter-soft meat would be served with green peas and Polish-style kasha. After dinner, we would sit and talk. Bernard’s oratory was well-honed; he had a fund of anecdotes about his own stage career as well as an encyclopedic knowledge of Yiddish theatre history. Harry was a much more reluctant raconteur, but his own story was even richer, and much darker.

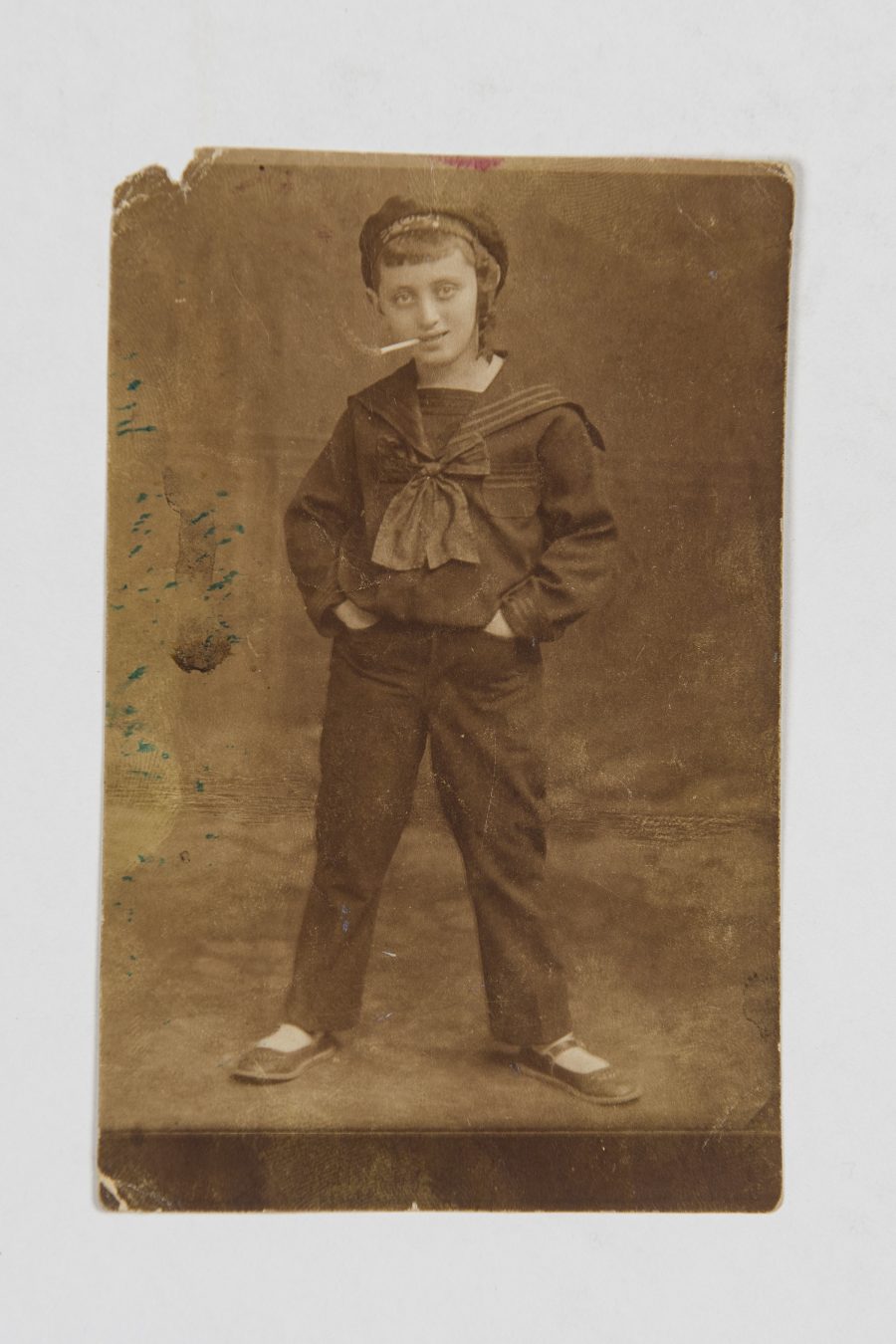

Harry Ariel in costume as a child actor, Łódź.

By the time I got to know Ariel, he was in his early seventies, struggling with poor health, but always with a shy smile on his face. After a life marked by poverty, tragedy, dislocation, and unimaginable privation, his modest lifestyle in Whitechapel’s back streets offered plenty of reasons to be cheerful. Selfridges’ steak was his one luxury, and those shopping trips to the city center seemed to symbolize the security and freedom that England had offered the young refugee actor. As for the occasional Yiddish theatre bookings that still came in from synagogue groups or cultural societies, these provoked bittersweet feelings. Yes, the show would go on, but the long gaps between bookings were a reminder that the vibrant theatrical culture both men had known in its heyday was now visibly on life support.

Harry had been born in Odessa in 1915 while his parents were touring with Misha Fishzon’s traveling Yiddish operetta company. As I write this, I think of his heavily pregnant mother bumping over country roads in horse-drawn carts across southern Russia, before giving birth in a strange city.

Ariel and his father, circa 1916–1917.

Odessa was a long way from the Ariels’ hometown of Łódź, the industrial city that had mushroomed in the nineteenth century to become Poland’s economic powerhouse. Harry’s paternal grandfather Mendel was the proprietor of Heymishe mitogn (Home Cooking), a small Jewish restaurant where Łódź’s Yiddish theatre community came to eat and gossip. His mother’s father was a weaver, part of the large Jewish proletariat that gave the city much of its defiant, flinty character. I once asked Harry about his family, and his answer memorialized an entire theatrical dynasty:

My father’s name was Khayim Duvid Ariel, but on stage he was Duvid Ariel. Why? Because it was easier—not so many letters on the poster! My mother’s name was Rukhl Ariel. My father’s eldest sister Manya was a Yiddish actress who had lived in Russia from before the revolution. Father’s other sisters I knew well: my aunt Sonia was a very famous Yiddish actress; she lived very near to us in Łódź and her daughter Raya became an actress later on as a teenager. Aunt Beyla was the youngest and is still alive in Argentina, and still appears in Spanish films and in concert on the Yiddish stage. She is almost 90 now. Then there was Ruzhe Ariel, a wonderful character actress, very funny; her husband was Hokhberg, a famous Yiddish theatre conductor-composer who was often engaged to perform in Warsaw.

The Ariel home was a redbrick tenement block at 24 Długa Street in a rough neigborhood. Kaminski, the kosher butcher who owned the block, sold meat from his shop on the ground floor. As you went higher, the tenants got poorer, until you came to the Ariel apartment — a single room with an attic window under the roof. In time, Ariel’s father became bed-ridden due to chronic arthritis, and his mother was the sole breadwinner. She had retired from the stage and become the props mistress, so in addition to three pull-out beds, a wardrobe, and a small stove for heating and cooking, the apartment was filled with boxes of stage props—imitation guns, candlesticks, and telephones.

Harry was a precociously gifted child actor, whose career took off in the mid-1930s, when he worked with many of the greatest names of the Yiddish stage in Poland. A stellar cast of local actors and visiting guest stars, they included Moyshe Lipman, Leo Fuchs, Lola Yakubovitch, Peysakh Burshteyn, Lillian Lux, Jack Rechzeit, Benzion Witler, Khayim Sandler, Shloyme Prizament, and Gizi Haydn. In the summer of 1939, Benzion Witler invited him to join his company in London as the “juvenile light comedian.” Ariel was overjoyed and applied for a visa and his first ever Polish passport. On the morning of September 2, 1939, he was about to leave his building to go to the passport office when he heard a commotion on the stairs. People were crying, shouting and screaming. “What is it?” he asked. “War!”

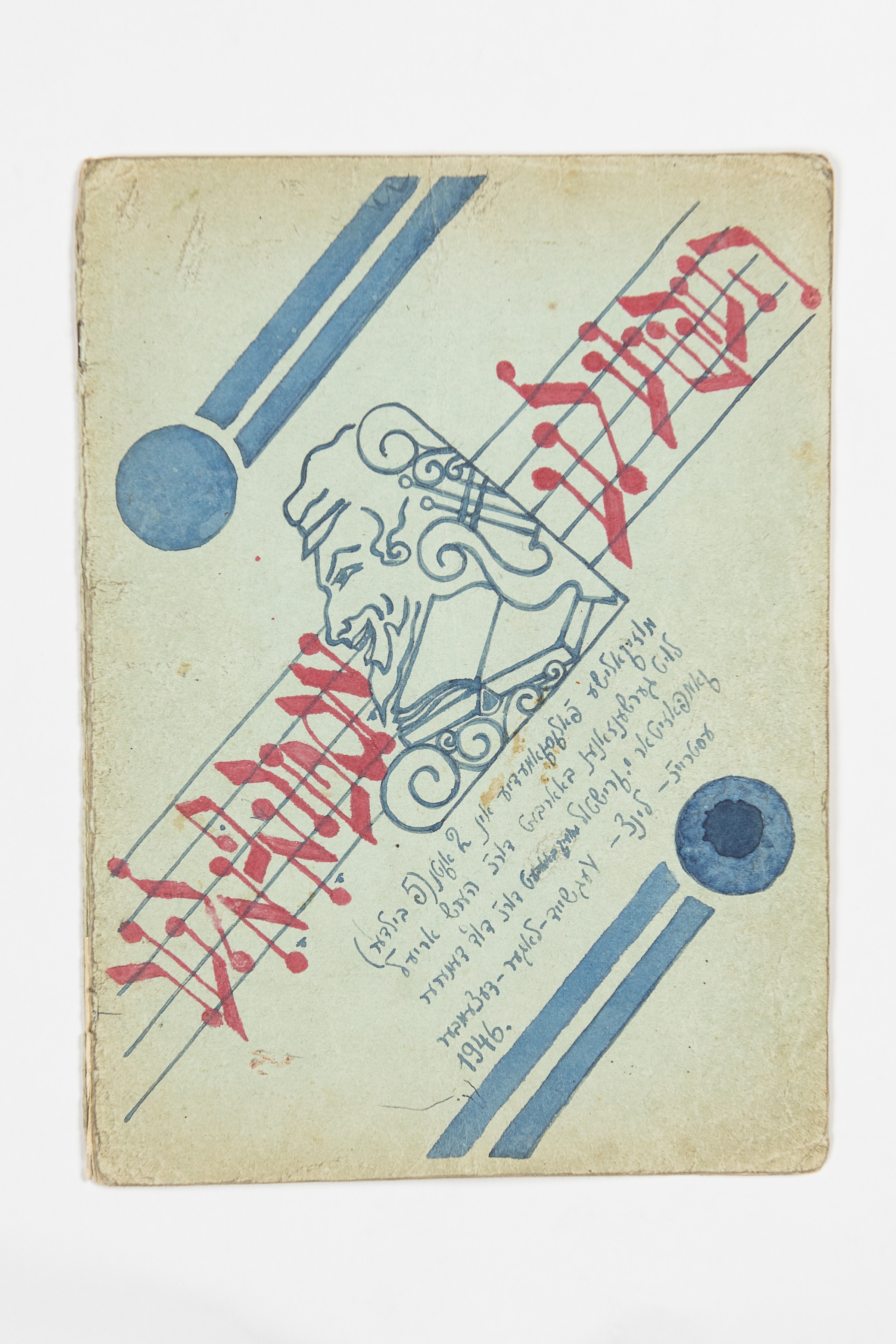

Harry Ariel designed and painted this cover for the handwritten musical score to Gershenzon’s Hershele Ostropoler, for a performance in the DP Camp in 1946, for which he recreated the actors’ parts from memory.

Opening page of Harry Ariel’s scrapbook of his years in Vegscheid Lager DP Camp in Linz, Austria, and his journey to London.

Page from the same scrapbook—revue performances in the DP Camp.

Page from the same scrapbook—revue performances in the DP Camp.

Page from the same scrapbook—revue performances in the DP Camp.

Final page from Harry Ariel’s scrapbook of his years in Vegscheid Lager DP Camp in Linz, Austria.

A page from a second scrapbook covering Ariel’s years in London and on tour in South Africa.

A page from a second scrapbook covering Ariel’s years in London and on tour in South Africa.

Harry Ariel in a comedy role with Sarah Sylvia.

Here Ariel is shown in a hospital in South Africa (second row from front, far left) recovering from tuberculosis while on tour.

Ariel fled east just in time to escape the Nazi occupation of Poland. At first he joined Ida Kaminska’s Yiddish theatre company in Białystok, part of the brief flowering of Yiddish culture in the newly-occupied Soviet borderlands. Then he spent several years as a prisoner of the Soviets, digging peat in a labor camp, a harrowing ordeal that left permanent physical scars. He returned to Poland after the war to discover that he was the sole survivor of his entire extended family. For Ariel, as for many other Polish survivors, the displaced persons’ (DP) camps of central Europe became a sort of temporary home. In Harry’s case, Wegscheid Lager DP Camp in Austria reunited him with a handful of his pre-war theatre colleagues. He reconstructed entire plays and sketches from memory for the scratch troupe, a company of survivors entertaining their own kind.

In 1948, he came to London together with Isaac and Dora Krelman, reviving the fortunes of the Yiddish theatre company at the Grand Palais theatre on Commercial Road. Harry’s all-round theatrical genius as actor, director, lyricist, playwright, and scenic artist (he was an accomplished amateur painter) made him the inspirational leader of the company in the 1950s and 1960s. By the time I came to know him, his cupboards contained dozens of his handwritten play scripts, notebooks with hundreds of song lyrics, and numerous older Yiddish play scripts from pre-war Poland, marked up with directions in his own hand.

Like all his London Yiddish theatre colleagues, Harry had been forced to earn his living in the “civilian world” when the Grand Palais closed in 1970. But in his case, a financial lifeline had come from an unexpected source. The German government undertook an extensive program of reparations after the war as atonement for Nazi crimes. Financial payments were made to Jewish welfare organizations and cultural projects, but also to individual survivors and others who could prove that their lives and livelihoods had suffered as a result of the war.

Ariel on stage at the Grand Palais, London, against a backdrop he painted, circa 1965.

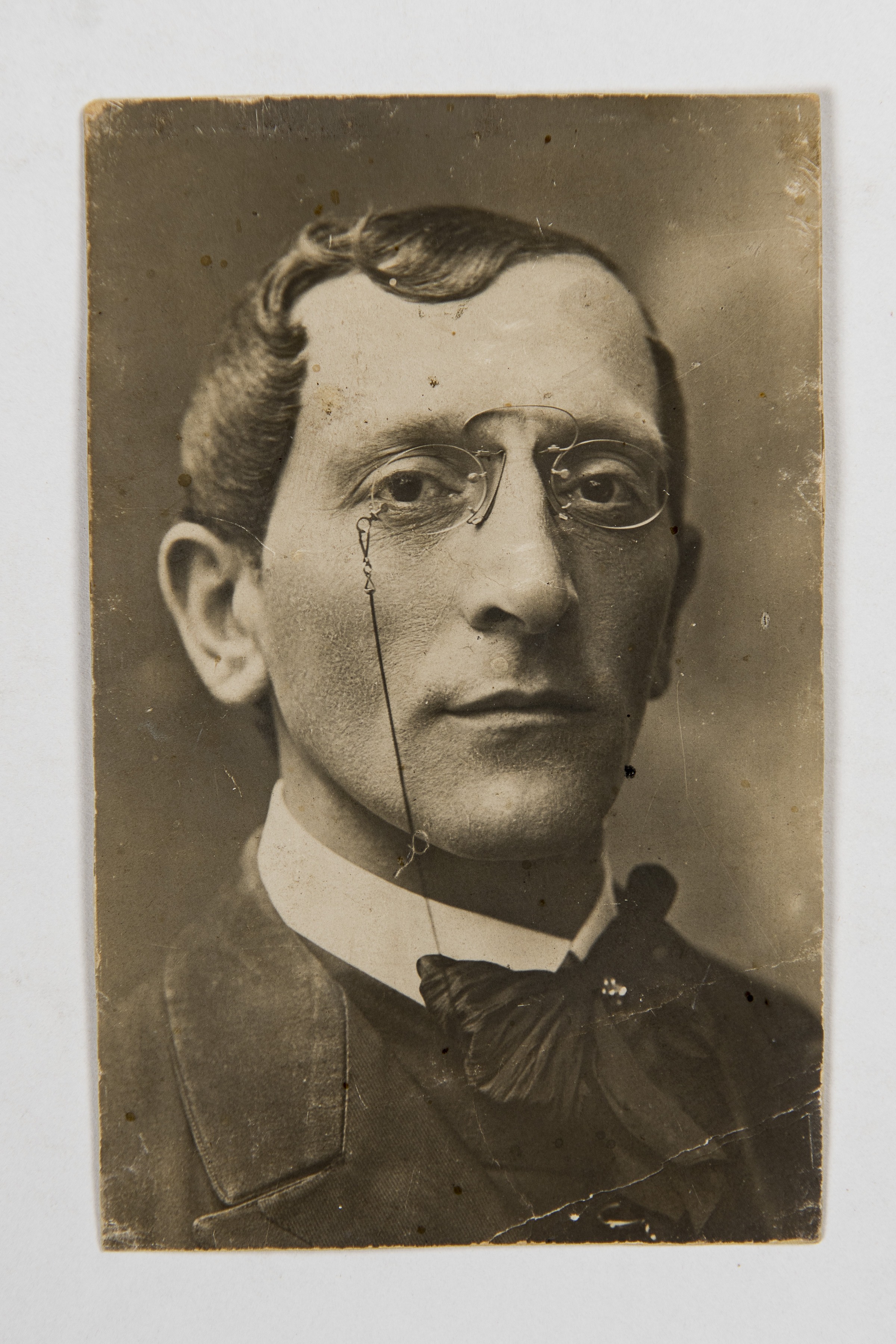

Ariel’s father, Khayim Duvid Ariel, circa 1912.

Ariel in Łódź, circa 1917–1918.

Ariel and his mother in Łódź, circa 1928.

Rokhl (Ruzhe) Ariel, Ariel’s mother, in costume in Łódź, circa 1915.

Ariel (front row, far right) with Izaak Krelman (front row, center) and company, 1940s.

In a pre-Internet age, with Poland firmly behind the Iron Curtain, and most material evidence of prewar Jewish life obliterated, finding this proof was no easy matter. At this point Zalmen Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater (Encyclopedia of the Yiddish Theatre) intervened in Harry’s life like a theatrical deus ex machina. His father’s biographical entry, from the first volume of the Leksikon (Warsaw, 1931) concludes with the sentence: “Zayn zun, Hari, shpilt kinder-roln” (His son Harry plays child parts). It was an incontrovertible piece of evidence, showing that Harry’s theatrical career was thriving well before the war, and he included it in the dossier he submitted for his reparations claim.

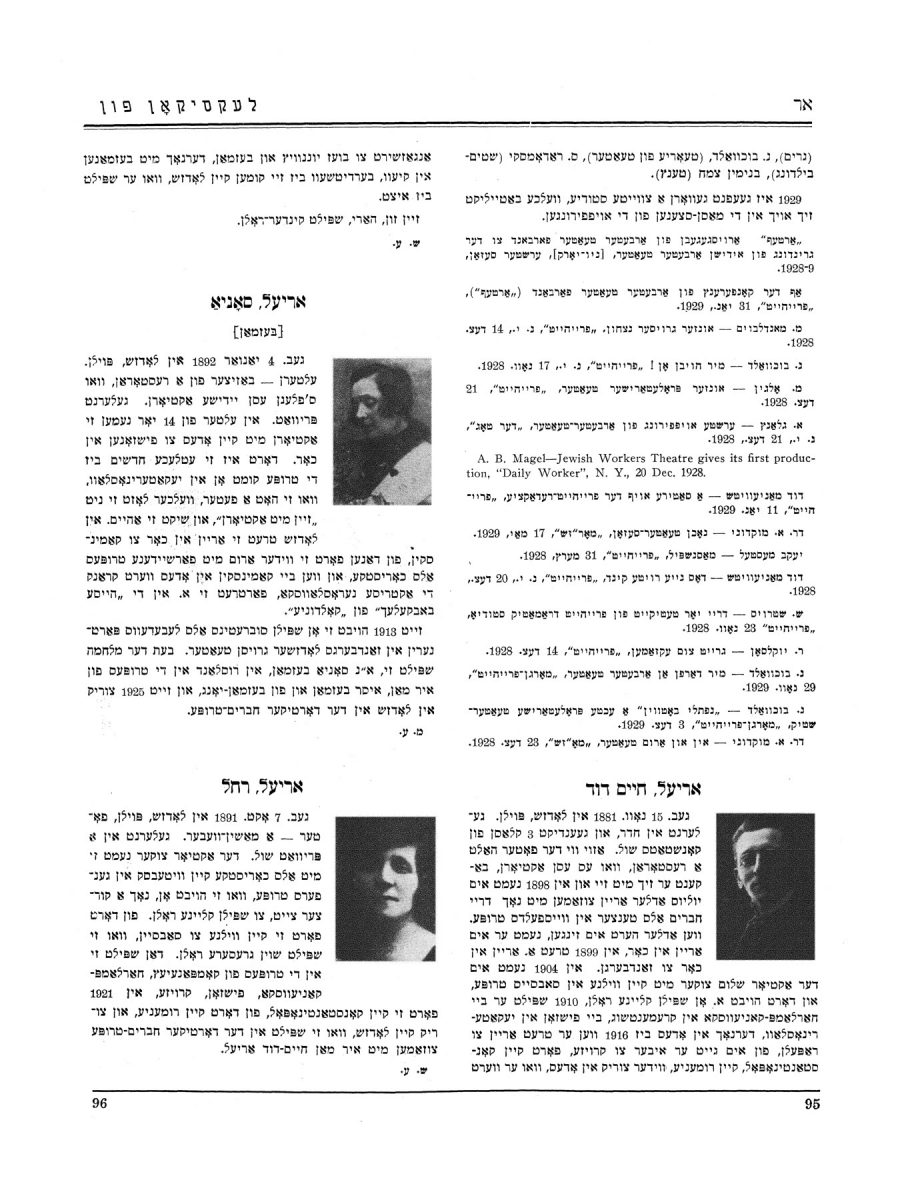

A page from Volume 1 of Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater featuring Harry’s parents, Khayim Dovid and Rokhl Ariel, as well as his aunt, Sonia. Harry is mentioned in his father’s biography.

So here is yet another remarkable achievement of Zylbercweig’s monumental sourcebook.

Dayenu—it would have been sufficient, as Jews repeat in the Passover song thanking God for everything he has done for the Jewish people—if the Leksikon was just an indispensable resource for later generations. Not just for the small community of Yiddish theatre scholars, but also librarians and archivists. And not just them, but today’s actors and producers who spin new theatrical gold out of the Leksikon’s base metal—its exhaustive lists of long-forgotten plays, production histories, and contemporaneous reviews.

Dayenu—it would also have been sufficient—if it was just a source of pride and validation to the hundreds of Yiddish stage personalities mentioned in its pages. For these “wandering stars,” so often belittled and marginalized within their own community, the Leksikon represented a towering monument to their professional achievements, a collective memorial that would endure long after they were gone.

But in Ariel’s case, Zylbercweig’s meticulous scholarship and eye for relevant anecdotal detail literally put food on his plate. Without the Leksikon, Harry was convinced that he would never have received his German government reparations pension. And without that financial lifeline, the little flat on Philpot Street would never have filled regularly with the welcoming aroma of Selfridges’ rump steak.

This article is part of a series celebrating the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project’s publication of volume seven of Zalmen Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater—the final volume of this monumental publication. The other related entries are found here and here.