Yiddish Lives, Smirks, and Breathes: Restoring Community Theatre into Yiddish History

C. Tova Markenson

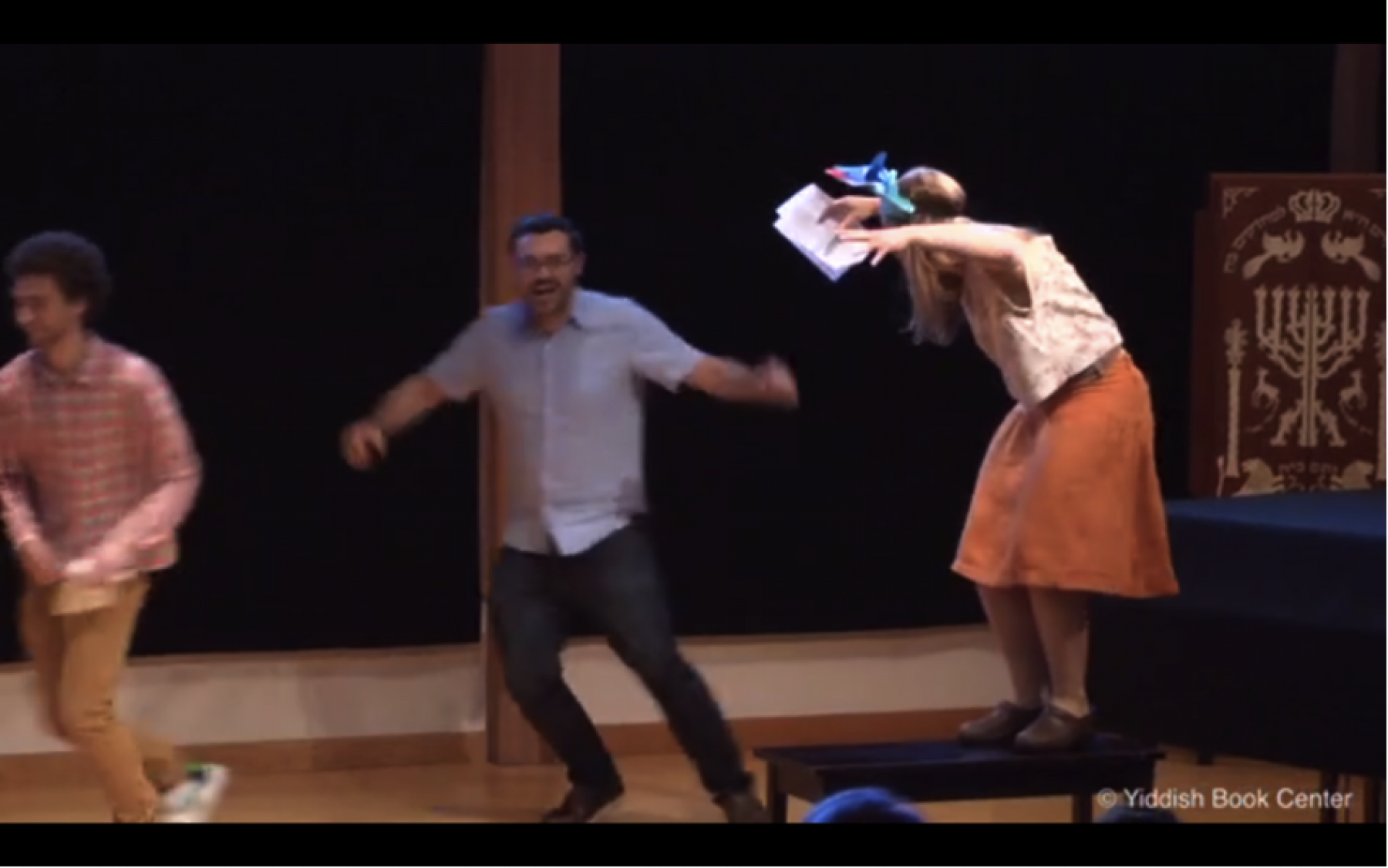

Diving off of the raised proscenium stage, I don a fish mask and begin to swim through the audience. “Vu zaynen di fish?” (Where are the fish?) a townsperson from Chelm, a folkloric Jewish village, asks the head of the community. Scanning the audience-turned-ocean, the Rosh Hakol calls out “Marco!”—I cry back “Fish!” instead of “Polo,” and the audience laughs at our twist on a familiar children’s game. The scene’s absurdity escalates as the Chelmsman follows me into the sea, scoops me into his arms, and runs back onstage. Standing on a piano bench, I widen my arms and deepen my voice to signal my transformation into a Fish-Dybbuk. “A Fish-Dybbuk?” the Chelmsman asks confusedly from across the stage. Shrugging, I concede that he’s right, a Fish-Dybbuk is “zeyr modne,” “very strange.”

Our performance, entitled Beginner chelm skit, was one of three new plays that premiered in July 2015 at the Yiddish Book Center, a non-profit organization that disseminates Yiddish books and hosts educational programs in Amherst, MA. This past summer at the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program, a seven-week intensive language course, I was one of eleven Yiddish speakers to write, produce, and perform original Chelm stories, or nonsensical Jewish folktales, for a private audience. Dr. Asya Vaisman Schulman’s communicative pedagogy inspired the collaborative performances we created for the Steiner Program’s culminating show. Beyond Beginner chelm skit’s pedagogical virtues, our play embodies a central problem in Yiddish theatre historiography: community-based performances are reservoirs of Yiddish culture, yet they have routinely been excised.

Jewish thinkers have long undervalued Yiddish theatre’s socio-cultural and political sway, largely because of Yiddish theatre’s close connection with amateur performance. Lacking published—or even written—scripts, such ritual performances were difficult to circulate and remain nearly impossible for historians to trace. Similarly, our Chelm play was handwritten on loose-leaf paper and was performed just once. While a videographer recorded the show, the film is, understandably, private. We developed and conceived the narrative to share two-semesters worth of learning with a trusted community of peers, not a public audience.

Even though a performative afterlife did not motivate Beginner chelm skit, our play was in dialogue with Yiddish performance history. For example, the Fish-Dybbuk character that I played reinvents the most-produced Yiddish play in history, S. An-sky’s The Dybbuk (1913-1916). In Beginner chelm skit, the Fish-Dybbuk’s flippant cameo rejects the dark, serious mood of An-sky’s fantastical drama. While at first the Chelmsman runs away from the Fish-Dybbuk, his simple question—“A Fish-Dybbuk?” – swiftly conducts the exorcism that impels An-sky’s canonical work. As the Fish-Dybbuk reflects on her existence in the pause that follows, audience members may simultaneously consider what it means for a hundred year old folk demon to continue dominating the Yiddish stage. Rather than dismissing the Dybbuk’s persistent presence, our Chelm play leverages satire—another Yiddish theatre hallmark – to re-imagine An-sky’s Dybbuk. “You’re right, I am just a fish,” I break the silence to ambivalently admit. With that, we move past the century-long drama that has haunted the Yiddish stage.

In our Chelm play’s finale, music further advances Yiddish theatre’s collective repertoire. While reprising an earlier rendition of “Ale Brider,” a socialist Yiddish folk tune, we participate in the tradition of adding on new verses. Mirroring the song’s rhyming structure that begins, “We are all brothers, oy oy, all brothers / and we sing happy songs, oy oy oy,” we sing:

Un mir zaynen ale fish, oy oy ale fish,

Un mir shvimen aftn tish, oy oy oy

We are all fish, oy oy, all fish

We swim on the table, oy oy oy

Blurring the boundaries between audience and performers, Beginner Chelm Skit insists that Yiddish is not a rusting antique. In plays that are staged at language-learning programs such as the Steiner Program, Yiddish lives, smirks, and breathes.