Tsipe (Tsipoyre) Abelman. Image courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

“Permit New Actors on the Stage?”: A 1905 Protest Letter by Tsipe Abelman

Tsipe Abelman

Tsipe (Tsipoyre) Abelman trained as a factory seamstress before performing in popular musical works on the Yiddish stage. In early twentieth-century America, she performed in Yiddish vaudeville with her husband, the famous singer-actor Beni Abelman (ca. 1865-July 13, 1929). But, unable to find work as an actor on protectionist, unionized stages in America, Tsipe Abelman had to return to Poland. In 1908, she participated in a production of Jacob Gordin’s The Brothers Luria, when the theatre critic Noyekh Prilutski wrote of her acting: “Mrs. Abelman (Sore-Dvoyre)…always performs with her husband and is very consistent, and this is a rare occurrence on the Yiddish stage.” 1 When the Abelmans could not find work in Warsaw, they performed concerts and skits in shtetls and in Hebrew events for Keren ha-Yesod. Abelman was deeply devoted to her husband and often demanded that he be honored as a pillar of the Yiddish theatre. She was killed by the Nazis in Poland. 2

While in America, Tsipe Abelman published an article in the Forverts (Jewish Daily Forward), “Permit new actors?” (May 11, 1905) where she protests the exclusivity of the Hebrew Actors’ Union, which she refers to as the Yiddish Actors’ Union, but suggests it might be called a “trust” because of its notoriously monopolistic tendencies. Abelman describes the Hebrew Actors’ Union in meaty revolutionary language as “despotic” and ruled by its own brand of tsarism.

This entry is part of the DYTP’s Women on the Yiddish Stage: Primary Sources project.

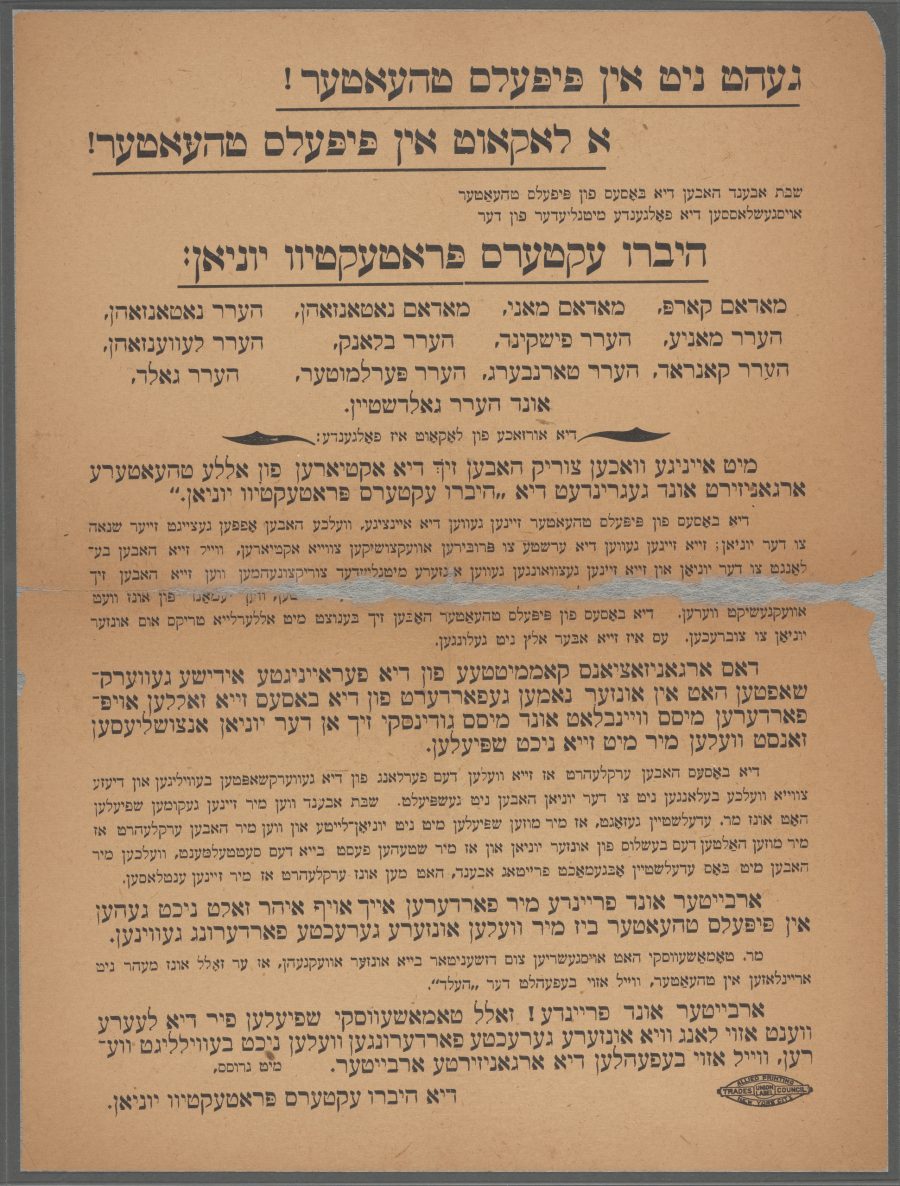

Hebrew Actors’ Union poster, 1899. Source: New York Yiddish theater placards, Yiddish theater collection, Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library.

“Permit New Actors?”

Originally published as Mrs. Abelman, “Lozt men tsu naye aktyorn?” Forverts, May 11, 1905, 5.

Translated by Anonymous.

Honored Mr. Editor:

I have been waiting for an opportunity for a very long time to express my opinion, or rather my protest, against the Hebrew Actors’ Union, which should certainly be called “the Hebrew Actors’ Trust,” and I am very glad that the Forverts was finally the first to have the “gall” to open its columns to this serious and simultaneously very important question: “Does the Yiddish Actors’ Union let in new talent?”

I say “gall” because not all newspapers would bother with such “nonsense.”

Their rule is, we’re better off not talking about it.

But let’s get to the point. The actors have united and founded a union. It isn’t even suitable for art to be restricted—for this we will forgive them—but we would have to be blind and foolish not to see what’s happening in said union.

Don’t forget, dear reader, that this association of actors is built upon the power of poor workers, and what makes them better than any other union on the East Side? And yet, look at how it takes advantage of the power it has received from the other workers.

But all must come to an end. The pitcher will only hold up until its handle breaks off. The public has kept silent for a long time, but now it won’t be silent anymore. What does that mean? A group of actors of the lesser sort has been formed of actors of the lesser sort, because the stars don’t belong to the union, and the managers neither, of course, and they have put a lock on art. The question is, though, what gives them the right to control the Yiddish stage? What rights have they to monopolize the stage as far as closing the doors to all who want to be able to accomplish something on it?

Who are they, these so-called critics, who judge the “tests” of who performs well and who doesn’t? It is simply a childish game. Let’s see how those “tests” take place.

The candidate is ordered to put on makeup and demonstrate jumping or dancing and doing all kinds of grueling work.

And the holy experts nearly split their sides with laughter. Now, dear reader, imagine how much courage and energy the candidate needs to show his talent in front of the owners of the art. If the Yiddish actors really want, as they say, nothing but good forces on the Yiddish stage, they should themselves learn to act first, or they should declare an edict that nobody has any right to perform on the stage until they bring an attestation from the drama school where they graduated.

I’m asking you, honorable theatre-goers, isn’t it laughable that a bunch of actors has united in a trust not to let in any new talent, be they even better than them until… they all die.

And their demands? The 100 dollars, and now, proof that you have performed for six months in the provinces. Go ask them if they have shown such official documents to anyone. Quite simply, the candidate is confronted with so many difficulties he can do naught but spit on the whole union and their demands altogether.

Tsipe (Tsipoyre) Abelman

Indeed, it’s high time the honorable public understood and asked the actors’ trust for an explanation of what they mean with the kind of tsarism that reigns among them.

The American stage, as low as it is, devotes an evening to new talents—they’re given the opportunity to show their talent and the public is the judge.

On the East Side, there are many talented people without any hope of ever entering the actors’ union.

The union and its actions compel them to await the old actors’ deaths, when they will perhaps have a chance to enter.

Open the doors! Abolish the despotic demands, give the new talent an opportunity to audition in front of an audience! This must be the cry of all the theatre-goers.

Respectfully,

Mrs. Abelman.

Notes

-

1Zalmen Zylbercweig, “Abelman, Beni (Borekh-Moyshe), Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 6 (Mexico City: Elisheve, 1969), 4855–69.

-

2Noyekh Prilutski, Yidish teater, vol. 1 (Bialystok, 1921), 145–6.

-

3Zalmen Zylbercweig, “Abelman, Tsipe (Tsipoyre),” Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 5 (Mexico City: Elisheve, 1967), 4781.