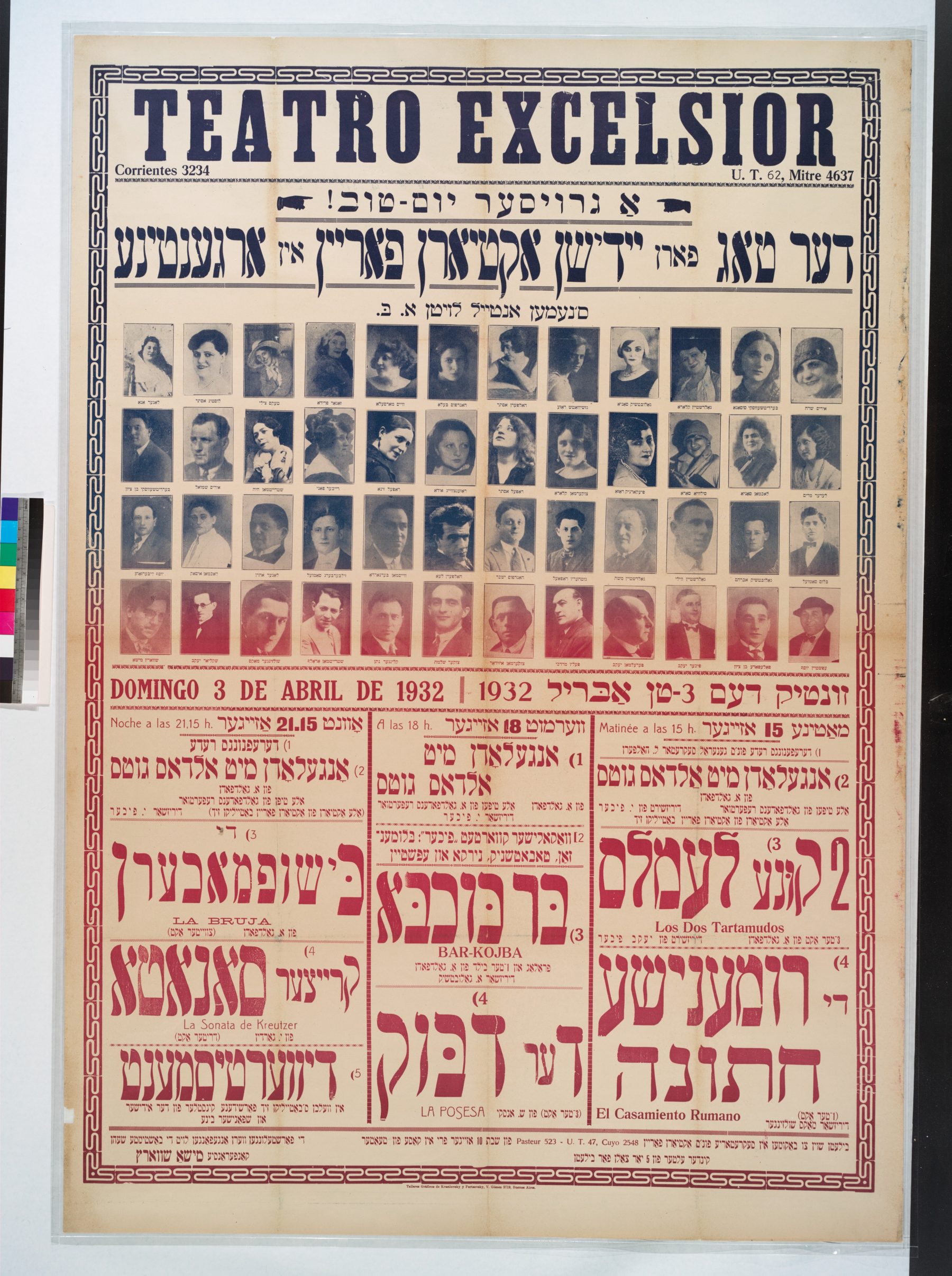

Bella Handfus and others at the Teatro Excelsior. Dorot Jewish Division, The New York Public Library, "Der tog farn yidishn aktyorn farayn in argentine," New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed November 20, 2017, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-...

Perla Rozenblum: A Porteño Life in Yiddish Theatre

C. Tova Markenson

Perla Rozenblum grew up attending the Yiddish theatres in Buenos Aires, and has seen and studied the transformation of the Yiddish theatre scene from its heyday to today. In this excerpt from Perla’s oral history, she shares her memories of attending Der yidisher folks teater (Jewish People’s Theatre also known as the Teatro IFT) and performances by touring celebrity actors, among other stories that enrich our knowledge of Argentine Yiddish theatre and culture.

DYTP member Tova Markenson, a graduate student at Northwestern University conducting research for her doctoral thesis on Yiddish theatre in Argentina, recently interviewed Perla about those experiences. In this excerpt, Perla shares her memories of the 1930s and 1940s.

On Perla’s Upbringing

Why is it that I love the theatre so much? Because my parents, in Poland, went to the theatre a lot. My father arrived here in 1931, and my mother in 1932. What happened was they got married, and then my father came, and one year later he sent over the money so that my mother could come. Before that they lived in Warsaw for all their lives. My mother used to say that they were “Warsaw-niks.” But what happened? My father was a socialist, he was in the Bund in Warsaw starting when he was very young, and my mother was from a Zionist family. They were from very different upbringings. When they arrived in Buenos Aires, my mother said, “Let’s go to the theatre” and my father said, “It’s not culture. It’s all vulgar.”

My sister and I had the privilege of having a Zionist mother and a Bundist father. Why? Because my mother did want to go to see vaudeville, and so my mother brought us to vaudeville, and my father, when Der yidisher folks teater started, we all went to those performances. We had the good luck to see…much of what was offered, we had the good fortune to see [Joseph] Buloff, to see [Jacob] Ben Ami, to see Maurice Schwartz, and to see really great Argentine actors.

During this time, to go to the theatre in Yiddish was a whole different thing. Because it wasn’t just going to the theatre - first, you had to go purchase the tickets, and if you didn’t, they wouldn’t let you in. Second, you had to get dressed, and get dressed nicely. Then, you would go to the theatre and say “Oh! Look at who’s over this way! Oh! Look and who’s over that way!”

And now that so many years have passed, when I go to the theatre, and I sit down, and then turn down the lights, and if there is a curtain or if there’s no curtain, you know that something is going to happen, and you are about to share it with fifty or a hundred other people, it is one of the things that I love the most. And for this reason, I started to do a little research about the history of Yiddish theatre in Buenos Aires. That was, unfortunately - and unfortunately I say “was” because it doesn’t exist and longer - it was a moment of so much richness.

Building Teatro IFT, the Theatre of the Jewish Left

There’s one thing that I have to tell you. It’s about Teatro IFT, Der yidisher folks teater, and not just because my father was a socialist and from the left, and the IFT was the theatre that came from the movement of the left of Buenos Aires, but also because it was the only theatre in Yiddish in Buenos Aires that was able to have its own building.

The idea to have an independent theatre began in the year 1932, in a kitchen made of wood in a conventillo (tenement) in Buenos Aires. In it was group of actors, and this kitchen was the kitchen of Sarah Eichenbaum…The actors asked themselves, “Where are we going to have a theatre? Where could we begin to rehearse?” It would have been impossible to do so in a conventillo. And so they went to a Jewish institution that fed the hungry - I don’t know what they had to eat, a plate of soup or something like that - and they asked the man who worked there who said “alright, that’s fine, I’ll give you a place so that you can come in the evenings to rehearse,” but when they finished they had to leave everything as they found it. And like that, they rehearsed. And this is where they put on, the following year, a theatre performance. This was in 1932.

In 1937, they began to consider the possibility of having their own theatre instead of renting space. They purchased property on a street called Boulogne Sur and there they laid the groundwork. Imagine all of the people standing around helping with the groundwork. My father was a tailor, what did he know about these things, nothing, nobody knew anything about it, but everyone had the opinion that the theatre had to be strong, that it had to be well-made.

How did they construct the building? Where did they get the money? The money came from the Jewish community. Everyone put one peso, two pesos, some cents. It was made entirely of brick. For example, you would buy your brick, and it would cost you one peso. You would be asked, “How many bricks are you going to put down? Five bricks?” And like that, with the support of the people, they created a theatre.

The stage was the only stage in Latin America, except for Teatro Colón, with a stage that was circular and revolved. It was a marvel. The lights, the seats, everything. They inaugurated the theatre with a performance by Sholem Aleichem, and the stage revolved. I’ll never forget it, I could barely stay in my seat because it was - it was all magic… because it was our theatre.

I think that this was a very important moment. The Jewish community would say, “you don’t walk to the theatre, you run to the theatre.” It was a place for socializing. After leaving the theatre, those who could went out to have a glass of tea at the Comerciál which was a place like the Royal in New York, here it was the Comerciál that was a place where they served you tea with lemon, tea in glasses, and there were Jewish pastries. And then later, after that, the actors arrived!

“Who watched the kids?”: On Co-operative Childcare for Yiddish actors

If it was difficult to be an actor, it was even more difficult to be a Jewish actor! For example, one time I interviewed - what was the name of this woman? - Handfus was her maiden name. She was the daughter of Bella Handfus. Bella Handfus was in many performances of the Excelsior Theatre. And so, I started asking her what her childhood was like. And she told me that it was not easy. They were dying of hunger.

The actors were putting on one show a week. And so, as soon as they finished one show, right away they had to start rehearsing for next week’s performance, and learn an entirely new role. In the morning you had to rehearse, in the afternoon you had a performance, in the evening another performance, sometimes there were three performances a day, and so what were you going to do with the kids?

I asked her, “Who watched the kids?” And so she told me, that various actors got together and hired a woman, a Jewish widow, who had a little bit of a larger apartment, and so they got together a few mattresses, and that’s where the kids ate and slept, and this woman brought them to school, and they paid her for it. And that’s how they organized, as if they were a small co-operative. And once a week, they went to their parents’ house, but where was their parents’ house? In the theatre! And where did they sleep? In the dressing rooms. It was not an easy life.

Meeting Señor Buloff: On the Arrival of actors from Abroad

I remember when Pesach Burstein arrived, this made a big impression on me, he showed up in a long suit, all covered in sequins, the fabric could have been a shmate (rag), but on stage it looked great.

Ben Ami and Maurice Schwartz, were giants, giants of the theatre in the United States. And the Argentine actors, non-Jewish ones, knew this, too. When the Argentine actors found out that Maurice Schwartz and Ben Ami were coming, they were the first in the audience. They came without understanding a word of Yiddish, it didn’t matter.

Ben Ami was an open kind of guy, and so the Argentine actors requested a performance from him. What did he do? The performance finished at midnight, which was normal. At 1:30 in the morning a performance began for actors, for students of the theatre. He performed different parts of all of his roles, and he spoke and explained in English with translation. This finished at five in the morning. After everyone went to work the next day.

I remember when Buloff came. When the show finished - it was an adaptation of I. J. Singer’s Di brider Ashkenazi (The Brothers Ashkenazi) - we were in the lobby waiting to say hello to one of the actors, and I saw Inda Ledesma. Inda Ledesma was a great actress of the Argentine Theatre. She was waiting as if she was a young student, but she was already famous. She said, “I want to say hello to Señor Buloff.”

“We have to defend our culture”: On the Intersection Between Yiddish Theatre and Politics

There were certainly political moments, for example in the 1930s, there was a military regime of Hipólito Yrigoyen. Leading the country was the nationalist, antisemitic right wing. I remember one time we were all going to the IFT - my father, my mother, my sister, and me. My sister was six years older than me. And so we were at the theatre. I remember that my father leaned over to my mother to point someone out to her. And this person, I will never forget this, was very short, wearing a long brown overcoat, and he had a big belly - the overcoat went like this over his belly - and after a time he walked up to someone from the IFT to say that they canceled the show due to a police ordinance. When we arrived back home, my mother and my father were talking about why there wasn’t a performance, they spoke of this man. He was a Jewish informant who worked for the fascist Argentine police.

In 1945 it was a very difficult year because there was the war in Europe, and they didn’t know about the concentration camps but they knew that nothing good was happening. And so began a movement through the newspapers, saying that we have to defend our culture, we have to continue going to the theatre.