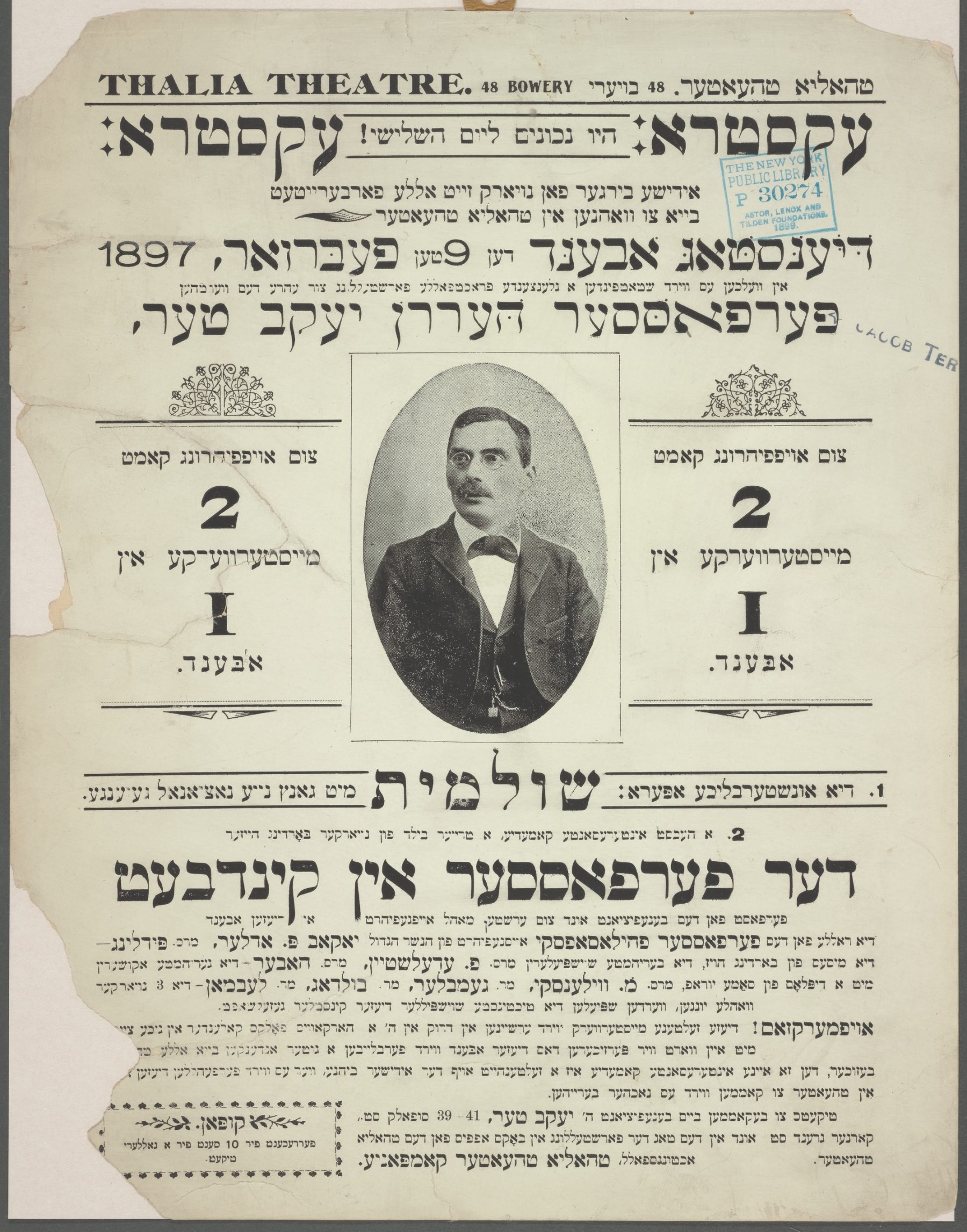

Avrom Goldfaden's Shulamis. Dorot Jewish Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c5e91ae0-...

Brush Up on Your Yiddish History Plays

Sonia Gollance

The parodic play, The Complete Work of William Shakespeare (Abridged), represents the Bard’s history plays through a football game where players vie for the English crown. King Lear even gets a penalty as a fictional character. This bout is an ingenious choice for the work of a playwright who focused his historical plays on British royalty. But that leads us at Plotting Yiddish Drama to wonder: how would you represent Yiddish historical plays?

It would probably be a grand spectacle. Forget the politics of succession—Yiddish theatregoers wanted operettas! The favorite genres for New York Yiddish theater audiences at the turn of the twentieth century were “operettas, musical comedies, and melodramas with musical underpinnings.” 1 The historical repertoire was no exception—music and dance numbers were beloved by theatre audiences. The lullaby “Rozhinkes mit mandlen” (Raisins and Almonds) from Avrom Goldfaden’s historical operetta Shulamis was incredibly popular onstage and off. In fact, the Jewish-themed episode of the Australian television series Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries (based on Kerry Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher novels, set in 1920s Melbourne), is called Raisins and Almonds in reference to the song. Too bad neither the mystery novel nor the television episode mentions the theatre connection.

Yiddish historical dramas weren’t dry, but they might be “baked”—playwrights like “Professor” Moyshe Hurwitz who were under pressure to create new dramas quickly added “a superficially Yiddish flavor to somebody else’s play, by giving it a Yiddish title, by giving the characters Yiddish names, and by setting them down in Eastern Europe or the Lower East Side or ancient Palestine.” 2 When his rivals at the Rumanian Opera House decided to perform a play about Jews in fifteenth century Spain called Don Isaac Abravanel, Hurwitz “simply rummaged up a play about a hermit by the popular German playwright Kotzebuë, adapted it violently, named it Don Joseph Abravanel, and managed to open it, barely rehearsed, before his rivals knew what hit them.” 3 While some might call this idea half-baked, Yiddish theatre audiences seem to have thought it was completely well done.

And of course there were particularly popular historical periods to portray on stage: ancient Israel and medieval Spain. Shulamis is probably the best-known example of a play set in ancient Israel. Written in the 1880s during Goldfaden’s romantic nationalist period, Shulamis would provide historical affirmation for generations of (Eastern European) Jews, whether living in Czarist Russia, Nazi-occupied Poland, or the Soviet Union under Stalin. 4 If authorities complained that a production set in ancient Israel might be too political, perhaps even Zionist, artists could claim it was a light pastoral operetta that should not be taken seriously.

Our latest batch of historical dramas includes even more examples of works with Sephardic themes. In addition to the Hurwitz play, there’s another Goldfaden operetta, a Dovid Pinski drama with messianic themes, a verse drama by A. Leyeles about Marranos in Portugal, and Kadya Molodowsky’s dramatization of the life of Doña Gracia Mendes. In recent years, scholars such as Jonathan Skolnik and John M. Efron have investigated the appeal of Sephardic themes for German Jews. Feel free to use these synopses (and the plays themselves) to consider the things that fascinated Yiddish speakers.

In the end, it is difficult to come up with a tidy metaphor that works as well as a football match. Yet instead of being a problem, this lack of a single historical thrust speaks instead to the diversity––and unruliness––of the Yiddish dramatic repertoire. We invite you to check out the current batch of plays, as well as previous and future synopses of works set in the past. Draw connections between dramatic works and contemporary prose texts (for instance, Avraham Mapu’s nineteenth century Hebrew novel Love of Zion has parallels to Shulamis). Compare the ways family dynamics, class conflict, and religious disputes play out across time and space. Delve into the historical Yiddish repertoire, and let us know what you think!

Notes

-

1Nahma Sandrow, “Popular Yiddish Theater: Music, Melodrama, and Operetta,” in New York’s Yiddish Theater: From Bowery to Broadway, ed. Edna Nahshon (New York: Columbia University Press in association with the Museum of the City of New York, n.d. [2016]), 70.

-

2Nahma Sandrow, Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater, 2nd ed. (Syracuse University Press, 1996), 108.

-

3Ibid.

-

4See ibid., 61–62, 243, 333. See also Jeffrey Veidlinger, The Moscow State Yiddish Theater: Jewish Culture on the Soviet Stage (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2006), 162–63.