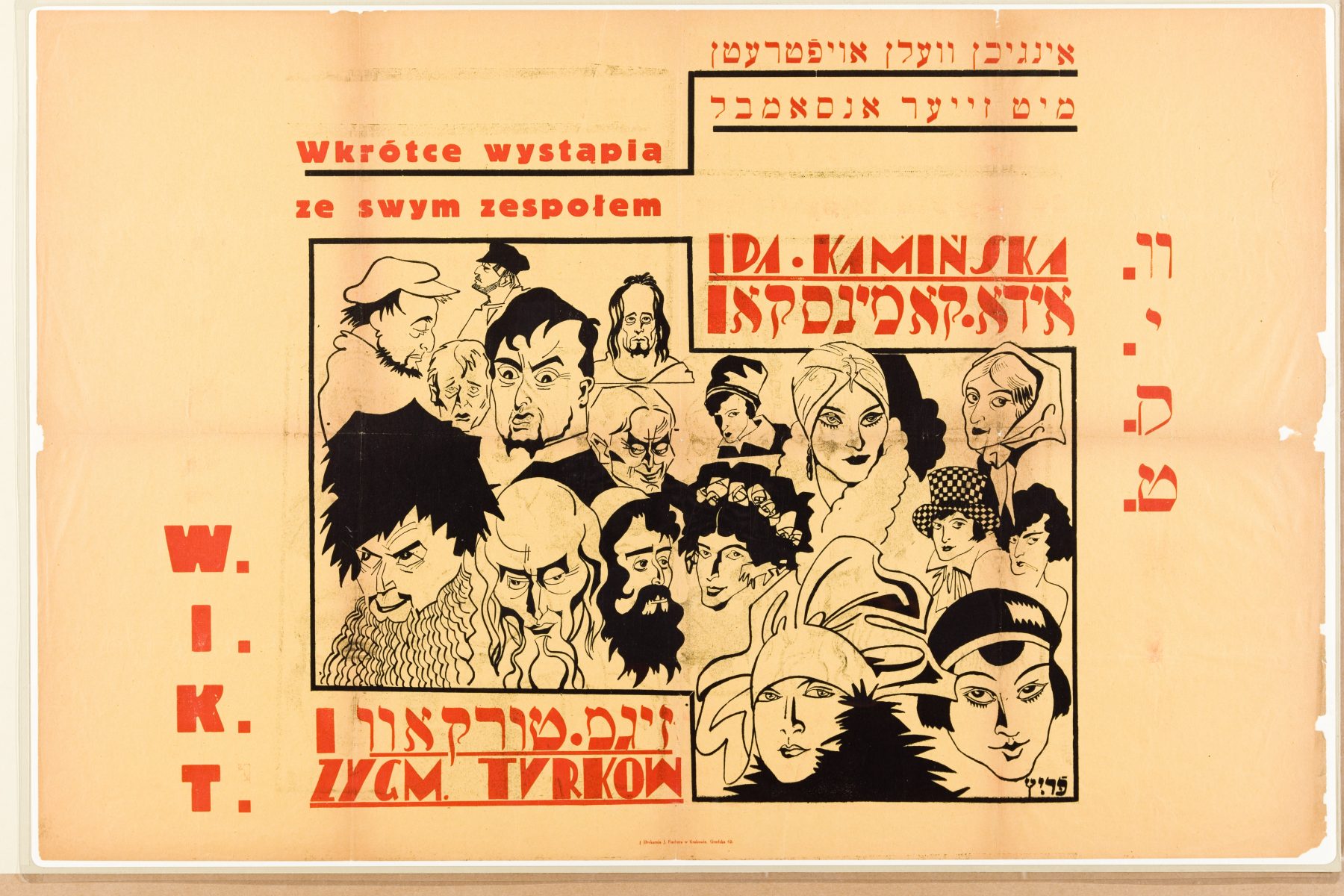

A theatre poster by Fritz Kleinman for Ida Kaminska’s production of Mir froyen (We, Women), a radical feminist work penned in Polish by Maria Morozowicz-Szczepkowska.

Visual Artists and Yiddish Avant-garde Theatre in Poland

Alyssa Quint

Artistic set designs and Yiddish theatre might call to mind Marc Chagall and his well-documented work for the Moscow State Yiddish Theater (GOSET). But collaboration between artist and Yiddish stage director was not the exception during the interwar years. A thoughtful piece by the visionary Yiddish theatre set designer Władysław Zew Wajntraub (Chaim Wolf Wajntrojb, 1891-194?), “The Significance of Backdrops in the Theatre,” that appeared in Literarishe Bleter, indicates the close relationship fostered between theatre and fine art. Wajntraub writes, “the approach of every artist in the theatre is to press into the content of the thing in order to pull out that which is deeply concealed in the work, and to express it boldly through sculptural-painterly ways.” Where do we begin to document the role of Wajntraub and his fellow artists in the Yiddish theatre?

Little of the material culture of Poland’s Yiddish theatre survives. The Yiddish theatre’s costume and set design budgets were typically meager, and the extent to which producers went to preserve, rather than re-use materials, is unclear. Of course, the war and the destruction it unleashed on Poland’s Yiddish theatre erased so much. Most tragically, the Germans murdered the majority of Poland’s Union of Yiddish Actors. Approximately five hundred of Poland’s Yiddish actors — including visual artists — are memorialized in the fifth volume of Zalmen Zylbercweig’s Leksikon fun yidishn teater (Encyclopedia of the Yiddish Theatre). In some cases, Jewish art was targeted for destruction or fell victim to the more general devastation of war and upheaval.

A rich vein of information pertaining to the visual aspect of Poland’s interwar Yiddish theatre is the Esther-Rachel Kaminska Theater Museum Collection, now being organized and digitized as part of the Vilna Collections initiatives at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. An enormous number of posters and programs credit costume and set designers by name, and many of the collection’s thousands of newspaper clippings —including hundreds of theatre reviews — describe their work in detail. Often these artists also designed the very posters and programs in which their names appear, and among the collection’s photographs are glimpses of these artists’ imagination and ingenuity. When everything is digitized, researchers will be able to piece together reviews, posters, and photographs with considerable ease.

Originally founded by Ida Kaminska in 1926 as a museum to honor her late mother, the legendary actor Esther-Rokhl (Esther-Rachel) Kaminska, and first housed in her mother’s Warsaw apartment, the collection grew exponentially even in its first year. Esther-Rokhl’s fellow actors preserved her memory by donating their own personal papers and photos, and in 1927, Ida gave the museum’s collection to the then-newly established YIVO Institute in Vilna. There, Max Weinreich actively facilitated its growth, soliciting material from “zamlers,” or gatherers, throughout the world, including avid collectors of theatre ephemera like theatre historians Jacob Shatzky and Sholem Perlmutter. Once in its new and expanded headquarters at 18 Wiwulski Street, YIVO allocated to its theatre collection a dedicated staff of eight members, a storage area, and a separate exhibition space. The Nazis arrived at YIVO’s headquarters in 1941 and destroyed or pillaged all of YIVO’s holdings. What survived from Kaminska’s collection had been set aside by the Nazis for their own purposes, and was discovered in Germany after the war by the US Army. Itself a survivor of the war, the collection is a repository of remnants from Poland’s vibrant Jewish cultural life.

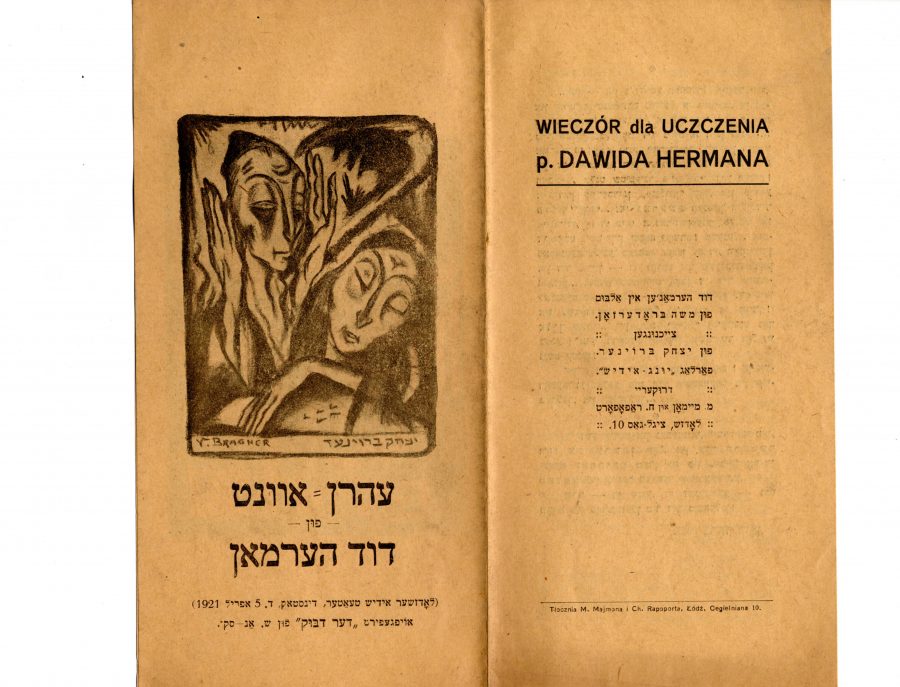

A program for an evening honoring the work of the director Dovid Herman designed by artist, Itshe Broyner.

Among those credited with set designs in the programs and posters in the archive are the visual artists Yoysef Shlivniak (b.1899 in Kiev) Zygmunt Balk (1873–1941), Fritz Klaynman (b. 1896), Dina Matus, and probably the most celebrated—and the only one of the group to survive the war—Mané Katz (1894-1962). Before creating sets for the Yiddish theatre, Balk worked at Lwów (Lviv) Opera House, created set designs for productions of Wagner (among others), and ranks among Poland’s most important twentieth-century painters. Shlivniak collaborated with the actor Zygmunt Turkow on his Yiddish-language staging of Stefan Zweig’s adaptation of Ben Jonson’s Volpone, and Matus, a member of the artistic-literary group Yung-yidish (Young Yiddish), conceived of the Jewish folk motifs and ambience of pioneering avant-garde director Michał Weichert’s legendary play Trupe Tanentsap (The Tanentsap Troupe) for the Yung Teater. Klaynman designed posters and programs, including a spectacular poster for Ida Kaminska’s Yiddish version of the radical Polish feminist play, Mir froyen (We, Women).

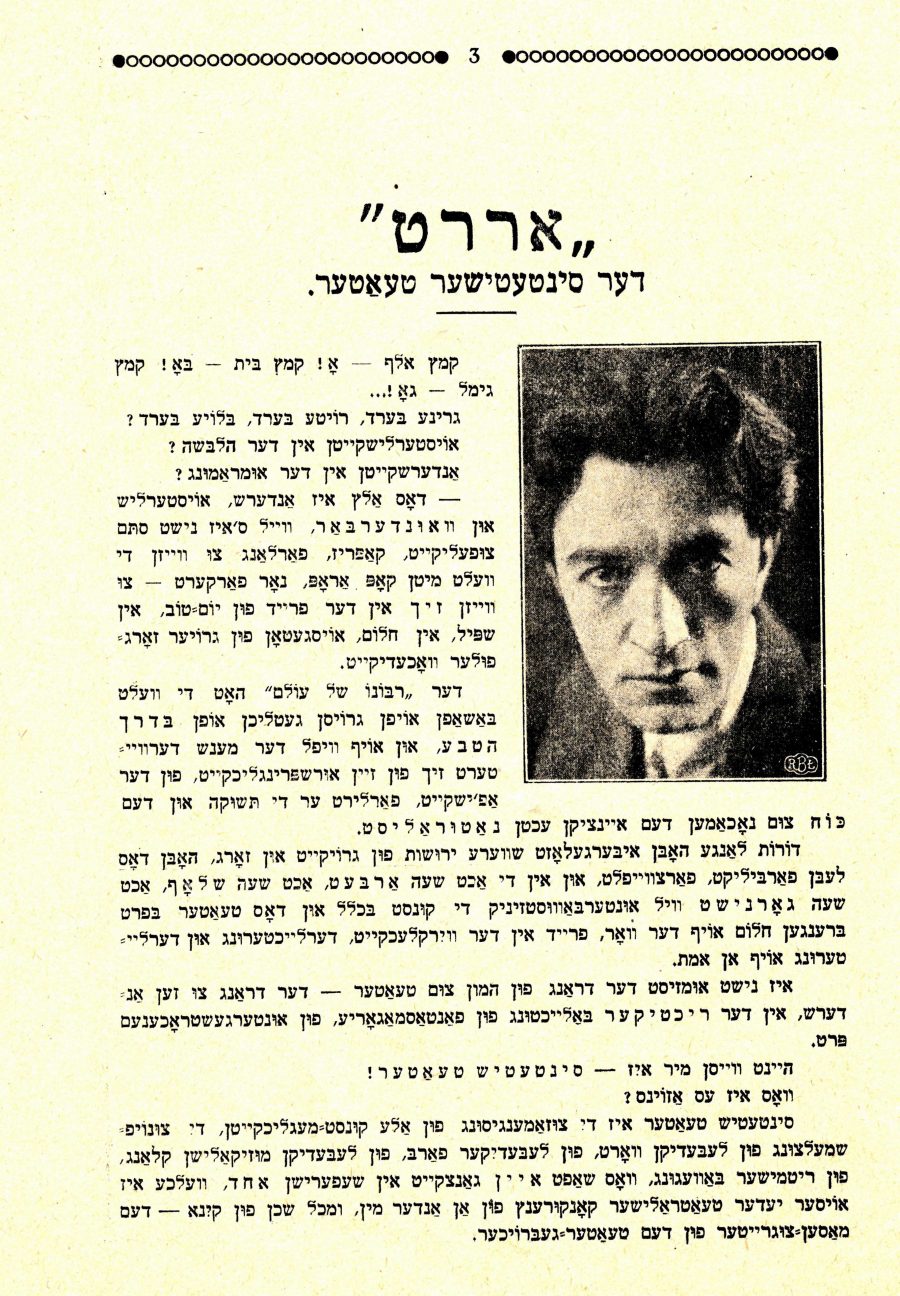

The verso of a program of a production by the theatre troupe Ararat featuring a picture of Moyshe Broderzon and his philosophy of “Synthetic Art.”

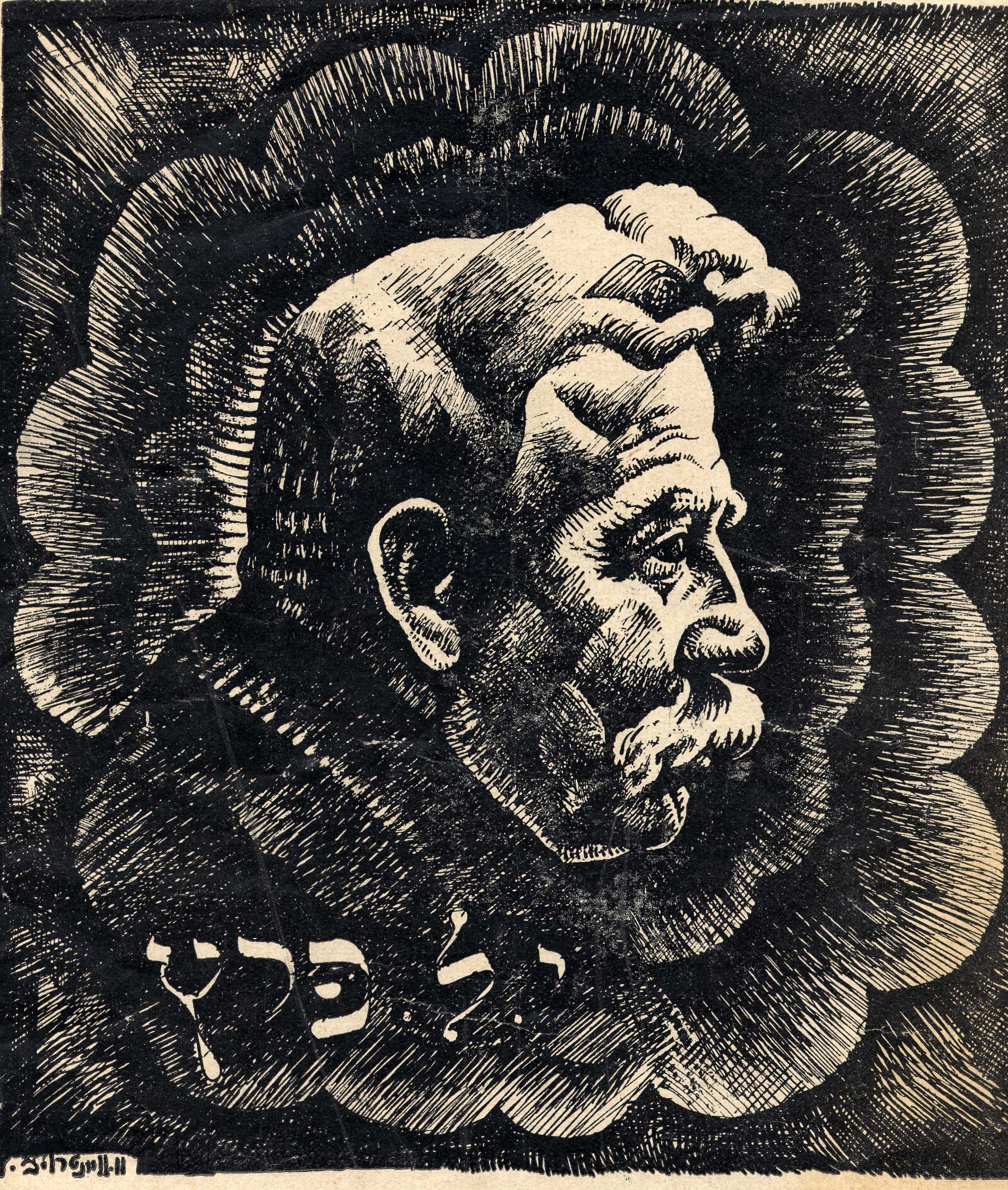

Born in Lyuvitsh (Łowicz), Poland, to Hasidic parents, Wajntraub was drawn to sketching and painting from a young age. Polish artists and art critics recognized Wajntraub’s raw talent and Poland’s Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts (Towarzystwo Zachęty do Sztuk Pięknych) supported his studies in France. In Paris, he met the Russian artist and set designer Leon Bakst (1866-1924) whose influence is responsible for Wajntraub’s decisive commitment to the decorative arts and theatre design. In his book, The Murdered Jewish Artists of Poland, Joseph Sandel writes of Wajntraub: “He was a fantasist, an Expressionist with mystic overtones.” Wajntraub worked closely with the modernist poet Moyshe Broderzon (1890-1956) and designed the set for his legendary opera Dovid un Basheva and I. L. Peretz’s Baynakht oyfn altn mark (At Night in the Old Marketplace). Wajntraub also worked with Weichert who directed a legendary production of Shabse Tsvi (Sabbatai Zevi) in Riga, where newspapers gave equal column space to both director and set designer. The reporter quotes Weichert as describing Shabse Tsvi as “a monumental performance, broadly imagined,” in which “the masses, actors, music, design and lighting come together in one artistic complex.”

Rendering of the poet and playwright I. L. Peretz by Chaim Wolf Wajntraub.

Focus on Wajntraub’s name from illustration of Peretz.

A scene from Peretz’s “Baynakht oyfn altn mark (“At Night in the Old Marketplace”).

Program for Peretz’s “Baynakht oyfn altn mark (“At Night in the Old Marketplace”).

Weichert and Wajntraub collaborated often and, in a number of their productions, deployed stages of various heights to create literal layers of meaning. In Leyb Malach’s Mississippi, about the “Scottsboro Boys” trial, actors representing white characters stood on higher platforms than did actors representing black characters, to emphasize their fatal inequality in American society. Wajntraub acknowledges, however, that a given space or venue sometime imposed limitations on an artist’s vision. In the same article, Wajntraub recalls that while his original design for Baynakht oyfn altn mark included a stage of multiple levels, his set could not be realized on the Warsaw venue’s stage, one of the first in which he worked. Tantalizing details such as these underscore how crucial was the visual dimension of interwar Poland’s literary Yiddish theatre production.

A photograph of the Had Gadya Puppet Theatre with puppets of Hitler, Einstein and other historical figures.

The Had Gadya Puppet Theatre.

The artist who gets the most attention in Zylbercweig’s Leksikon is Itshe Broyner (1887-194?), who, together with Moyshe Broderzon, the visionary composer Henekh Kon (1890-1972) and the writer and artist Yekhezkl-Moyshe Nayman (b.1893), established the Had Gadya puppet theatre in Łódź in 1923. Broyner was born in Łódź to a well-to-do family whose father was one of the pioneers of the city’s textile industry. After attending a Polish gymnasium, Broyner studied art in Poland and Berlin. In Berlin he also studied violin in conservatory, but finally chose to devote himself to visual arts rather than music. The Esther-Rachel Kaminska Theater Museum Collection includes a beautifully preserved manuscript of Mitn puter arop (Butter Side Down), for which Broyner created the design and carved the puppets. This trilingual play (in Yiddish, Hebrew, and Polish), was conceived of and performed as a Purimshpil in 1936, and the play included such historical characters as Vladimir Jabotinsky, Albert Einstein, and Adolf Hitler. Pasted into the manuscript are photographs of the puppets and set and their makers, as well as publicity materials that include a caricature-self-portrait of Broyner.

The programs and posters of interwar Poland’s literary Yiddish theatre reflect how much its ensemble approach extended to its visual artists. A spare five paragraphs published on the back of a program from a 1928 production staged by the experimental troupe Ararat (like Had Gadya, also pioneered by Broderzon) lays out Broderzon’s idea of what he calls “Synthetic Art.” “Synthetic theatre is the rushing together of all the art-possibilities, the together-blending of the living word, of the living color, of the living musical sound, of the rhythmic movement, which creates wholeness in creative oneness.” Broderzon’s Synthetic Theatre meant to deploy all of art’s modes of expression, and to do so, he assembled a group of artists to shape his productions that included painters and sculptors.

The gravestone of Esther-Rokhl Kaminska designed and sculpted by Yoysef Rubinlicht.

The gravestone of Esther-Rohkl Kaminska designed and sculpted by Yoysef Rubinlicht.

Some of these artists considered their work in the Yiddish theatre an adjunct to their main artistic pursuits, the output of which was, in many cases, lost during the war, presumably destroyed or stolen. As so many of these artists perished in the war, little was done afterwards to recover their work. The efforts of Josef Sandel, who remained in Warsaw and sought to document the dead artists’ work in as much detail as possible, are the exception. In some cases, the Esther-Rachel Kaminska Theater Museum Collection houses some of the only known evidence of their work as artists. The surviving evidence of their visual art and design work resembles shards of pottery crying out to be reconstituted. If not for the few photographs of Trupe Tanentsap published in Weichert’s memoirs, we would not know the work of Matus; if not for the archive , we would not know Broyner’s talent. Most of the sculptures of Yoysef Rubinlicht (of the extraordinary Polish-Jewish Rubinlicht family) perished with their creator. But at least one survives: the gravestone of Esther-Rokhl Kaminska, with its ornately carved bas relief.

The Esther-Rachel Kaminska Theater Museum Collection is far-reaching, and a systematic survey of all the visual artists whose work it mentions has yet to be done. The same goes for the choreographers, musical composers, and costume designers listed on so many of these programs. Such work will illuminate the multidimensional nature of the avant-garde and literary theatre of this most fruitful, and largely undocumented, chapter of modern Jewish culture. Here, the Yiddish theatre is an example of how art begets art and art preserves art.