Daniel Galay

An Interview with Daniel Galay

Ellen Cassedy

Daniel Galay is a prolific playwright, composer, and pianist living in Israel. His musical works have been performed by orchestras, ensembles, and soloists around the world. He writes for the stage primarily in Yiddish, but also in Hebrew, Spanish, and English. His one-acts, full length-plays, and satirical sketches have been performed in several countries and collected in several volumes. Galay is a longtime advocate for Yiddish in Israel. Here, Ellen Cassedy asks Galay about his career, working in Yiddish, and his contact with Yiddish culture and Yiddish theatre on three continnts.

EC: What are your roots as a Yiddish-oriented artist?

DG: I was born in 1945 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. My parents spoke Yiddish to me and my two brothers, and we had a lot of aunts and uncles who all spoke Yiddish. My father was fanatical about speaking Yiddish in the home. My mother was more liberal—and more fluent in Spanish. My father made his living as a tailor and was an actor in the Yiddish Folk Theatre. We often visited the theatre when he was in a play, and there we were exposed to art, music, and dance, and the various sounds of theatrical Yiddish. I began playing piano at five and graduated from the National Conservatory of Music in Buenos Aires.

The Spanish language and the Argentine mentality had a strong influence on my personality. Spanish is a world language with a wide historical range and rich literary history. It is central to who I am and how I’ve lived my life.

In 1965, I made aliyah and settled on a kibbutz. A few years later, I went to Chicago to further my musical education. In the 80’s, my wife Khane and I returned to Israel with our two children. At that point, I asked myself what I was doing to ensure that my children would benefit from the values and the language I’d absorbed as a child.

And so began my “Yiddish career.” It started with organizing informal gatherings in private homes and then branched out. I was the co-founder of an annual Yiddish journal, Naye vegn, which published prose, poetry, and dramaturgy by a new generation of Yiddish writers. I became the chair of Leyvik House, the Yiddish cultural organization based in Tel Aviv, which houses the Association of Yiddish Writers and Journalists in Israel, and an editor at the H. Leyvik Publishing House.

EC: What’s important to you about Yiddish?

DG: Yiddish is my identity and my inheritance. The language and its great literary figures are an unending source of knowledge, inspiration, and wisdom for me.

The situation with respect to Yiddish in Israel is always changing and very much tied up with the general ethnic and political situation. The position of Yiddish is far from what it should be, but over the years we’ve learned how to advance the interests of Yiddish. There are some in Israel today who are invested in learning mame-loshn, and this is the great hope.

I’ve expressed my views of Yiddish in Israel in several dramatic works. My satire Nadia in Hebrewland is about Hebrew speakers who denigrate Yiddish and a young woman who fights back against them.

And my satire Dance in the Airport is a critical portrait of contemporary “Yiddishland.” It is easy to fall in love with Yiddish and lose one’s critical eye. This is not healthy. In the play I present various types of Yiddish students, zealots who are fanatical about their dialects, entrenched professors. All of them want greater unity in the Yiddish world, but each of them also has an ax to grind.

The situation requires tireless activism on behalf of our cultural legacy.

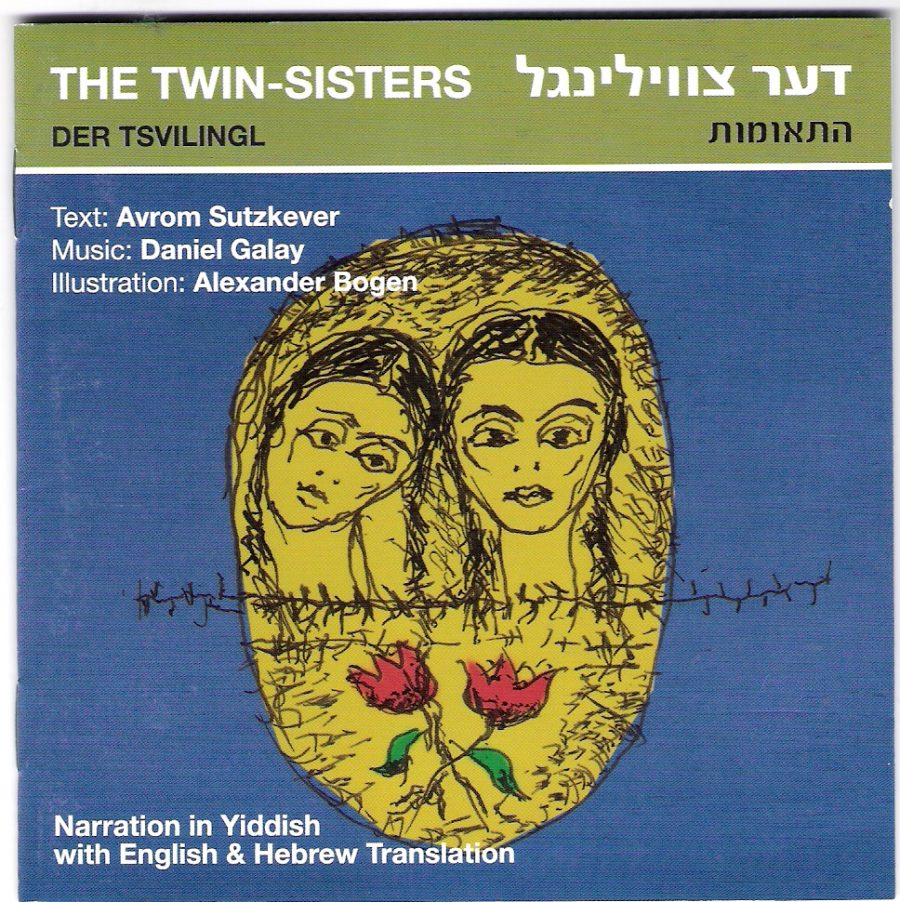

Galay’s composition “The Twins” (or “The Twin Sisters”) uses a text by Abraham Sutzkever and premiered in the poet’s presence on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday.

EC: Many of your works for the stage are heavily bound up with music. Many are multimedia and multilingual.

DG: Yes. My multimedia approach is a message in itself, reflecting the complicated relations we must contend with in today’s world.

I want to mention Tal Shahar, a real talent, the stage director of my operas, who rises to the challenges posed by the multimedia approach and achieves great results in a very short time. I owe her a lot.

EC: Your play Dayges is a good example of your multimedia work. The three different media—acting, music, and dance—seem to function as three languages.

DG: This play is very close to my heart. There are three groups—actors, musicians, and dancers—each with its own social class and identity. The actors are the worriers. The musicians are the kibitzers. And the dancers are the connoisseurs. Each group speaks in its own language, and their disputes become so intolerable that all three groups literally leave the stage, only to be coaxed back by the emcee, who calls on them to step up and fulfill their responsibility to repair the world. It’s a story with a happy ending.

I originally wrote the play for arts students to perform at the opening of a large auditorium in Germany, but in the end it wasn’t performed there. Now that it’s been translated into English [by the interviewer, Ellen Cassedy] I’m hoping for a matchmaker who will “bring the bride to the khupe.”

I’ve also written and produced four chamber operas. They include song, dance, music, and texts in several languages. Two of them are based on texts from Sh. An-ski’s famous ethnographic expedition of 1912-1914. In Chaim ben Chaye, which premiered in Dresden in 2008, the singers sing in Yiddish, the actors perform in German, and there are also dancers and a twelve-piece musical ensemble.

EC: Itshe Haystir is another good example of your multimedia, multilingual approach.

DG: Yes. It’s an avant-garde work in which an actor speaks in Yiddish, a female singer vocalizes, a pianist speaks through the keys of his instrument, and a percussionist serves as a witness to a love triangle. It was first performed in 2009 at Leyvik House in Tel Aviv. It deals with the alienation that today’s technology and mass culture impose upon us.

EC: Can you describe your general approach as a composer?

DG: I try to employ innovative sounds and techniques within the frame of classical structures. The great masters are my best teachers and my primary source of inspiration, but composers must also understand our own personal feelings and spirit and try to express them.

EC: Many of your works include dance. Why?

DG: Dance is a vital dramatic component. The language of the body is very useful. It speaks to everyone, is visual and dynamic, and conveys the rhythms of our times. For example, my drama Winter Is Here is a basically realistic play (not yet performed) that takes place in an old age home and presents a love story between two residents. In the text I indicate many places where a pair of dancers appears. Their presence is a little mysterious. It’s meant to suggest the outside world from which the residents are disconnected. It injects ideas of love, doubt, and stress that the actors themselves don’t express directly.

An image from Galay’s chamber opera, “Itshe Haystir” (1999), a work for singer, actor, piano, and percussion.

EC: You’ve worked a great deal with existing texts.

DG: Yes. My musical pieces with texts from Yiddish folklore have been performed in Israel, the US, South Africa, France, Croatia, German, Poland, and other countries.

And I’ve set to music the Yiddish and Hebrew texts of Abraham Sutzkever, Peretz Markish, Uri Zvi Grinberg, Zelda, Yehudah Amichai, and Tzvi Kanar, among others.

For example, my 2003 composition “The Twins” uses a text by the great Yiddish modern poet Abraham Sutzkever. I took the story from a work of prose by him. It premiered in Sutzkever’s presence on the occasion of his ninetieth birthday. I didn’t want to show him the music before the concert, since I was afraid of his reaction—but after the performance I looked at him and gathered that he was pleased. The work has several versions: for string quartet and narrator, for chamber orchestra and narrator, and the theatrical version that was performed at the Israel Festival in 2003.

Another image from Galay’s “Itshe Haystir.”

EC: Have you worked with other librettists?

DG: Dancing Anne Frank, a chamber opera first performed in Israel in 2016, has a libretto by the Turkish writer Tarik Günersel. The two of us are collaborating on another chamber opera about the life and work of Nikola Tesla, the scientific genius from Croatia. Another example of my use of another author’s words is Abush and Zoshke, a love story that takes places in September 1939 when the Nazis invaded Warsaw. It’s based on the autobiographical works of Abraham Mairkevitsh.

EC: Do your dramatic works have a political dimension?

DG: Yes, I think so. I try to express a critical attitude toward our era. The artist must contend with an establishment that is often very conservative, afraid of change and of new ways. The struggle can be very bitter, but a real artist has his internal spiritual power to draw upon. The artist must allow all his deepest emotions to burst with fire, no matter how conflictual they are, and then to create a new balance among them. An artist must represent a hope for the future. Merely to describe the world we live in—in itself not an easy task—is not enough. One must also suggest a better world with more justice and love.