Still from Labzik: Tales of a Clever Pup, courtesy of Jake Krakovsky

A Year of Yiddish Theatre in Covid: A Wrap Up?

Faith Jones

In the past year, we’ve covered a number of COVID-era online productions, from drag that draws on Yiddish themes, to Yiddish-inspired new plays, to a re-mounted classic, to long-ignored material and more long-ignored material. But these reviews barely scratch the surface of the outpouring of Yiddish performance that the past fifteen months have brought us.

In October 2020, as the American elections loomed, the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene created two versions of Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here. One was a multilingual collaboration with eight other theatre companies reading in English, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, and Hebrew, as well as the Folksbiene providing Yiddish. They also staged a full reading in Yiddish as a “community reading” with Yiddish speakers from around the world. Involving non-actors in this work, especially in the service of fighting fascism, is something of a return to the Folksbiene’s roots as an amateur theatre based in working-class immigrant culture.

In December, Yiddish New York produced a play as part of its teen programming. Collectively written and performed by a dozen teens in their separate homes, the performance combined historical Jewish material about plague weddings and Jewish housewives who resisted eviction with COVID-related questions about safety and community. All props and sets were homemade or “found” (a toy horse was placed in a large potted plant to create a forest glade). How glad was I to see these young people taking their place in Yiddish theatre? I’m sure you can guess how I kvelled.

In February 2021, the Congress for Jewish Culture created The Megile Cycle, a new interpretation of Itsik Manger’s poems know as the “Megile lider.” While there is a well-known musical based on the “Megile lider,” this was a new interpretation with the main story lines explained in English narration, while the poems were acted out in Yiddish. The Congress’s productions are streamed on their YouTube channel, which allows audience chat to roll along beside it. It is easier to use than Zoom’s chat feature and less intrusive on the performance. For this reason, the chat in YouTube seems to provide an audience outlet similar to hearing applause and laughter in a theatre. One particularly fun moment occurred when Eleanor Reissa, whose Vashti had just died on stage, joined the chat, only to be comforted by audience members on her demise. Inhabiting Vashti fully, Reissa remained deliciously camp and over-the-top.

In April, the Museum of Jewish Montreal presented a delightful short new work, Blut un blintzes (Blood and Blintzes) by Rebecca Turner—perhaps the first vampire play in Yiddish. The plot involves a Jewish day-school graduate and recently-turned vampire. She comes to see her rabbi to find out the Halakha on her new situation. The rabbi is delighted to have someone with whom she can discuss the finer points of ethical vampirism, but the two disagree and the repartee bubbles nicely. A favorite line was the rabbi, yelling furiously at the vampire, “I’m a rabbi. I don’t get mad—only disappointed!” An interesting aspect of this production was in the after-show talk, hearing actor Shuli Elisheva’s take on her character of the rabbi. Shuli Elisheva felt her voice is recognizably that of a transgender woman. She created a back-story for her character: the rabbi was a former AMAB Hassid who, after transitioning, went to JTS and became a Conservative rabbi. This also allowed her to use Poylish dialect, playing off against the young vampire’s YIVO dialect which was suitable for her character. A few times as they verbally sparred, the young vampire sarcastically mimicked the rabbi’s accent. The play is a farce, but there is something in the manifestations of blood in Jewish culture and history (menstrual taboos, blood libels, rules of kashrut) that makes it a bit more than that.

Still from Labzik: Tales of a Clever Pup, courtesy of Jake Krakovsky

In May, Los Angeles’s Pacific Resident Theatre produced a play version of A Bintel Brief, the Yiddish Forverts’s long-running advice column. This adaptation was well-suited to the online format as only one person had to talk at a time: the “letter-writer” would ask their question, and the actor playing editor Ab Cahan would answer it. By changing a hat for a head-scarf or adding a prop, cast members could quickly become different letter-writers. The choice of letters (from the English-language book) seemed designed for our era: vegetarianism, women’s rights, and ethical dilemmas abound.

Most recently, the theatre department at Emory University mounted a puppet theatre (puppy theatre?) version of Chaver Paver’s children’s stories featuring an intrepid dog, Labzik. This deceptively-simple format imparts an astonishing charm to the material, not least because of the history of puppet theatre in Yiddish. It also didn’t hurt that Labzik is set during the Depression, combining realism, fantasy, outrage, and idealism. All of this made it very suitable for our present moment. The artistry combined cut-out puppets with some animated elements, soundscapes, lighting and color effects, and background music. At the same time as this technical wizardry was underway, the audience was also allowed to see the puppet strings, retaining an old-fashioned feel. The introduction and all narration was in English, while dialogue was in Yiddish with subtitles. An international cast of professional and novice actors provided the voices. At fifty minutes, the production was perfect for the Zoom-era attention span.

Still from Labzik: Tales of a Clever Pup, courtesy of Jake Krakovsky

Two very different radio pieces from the Yiddish Book Center took online performance in the direction of audio plays. Both were translated by the actor Caraid O’Brien. The memoirs of Russian revolutionary Klara Klebanova, The Last Maximalist, was launched as a radiocast in October, in twelve episodes affectingly voiced entirely by O’Brien. In May, Sholem Asch’s metaphysical WWI drama The Dead Man was released online, with a large cast, atmospheric music, and complex sound editing. These pieces should inspire further audio, whether following the relatively simple one-voice reading or the full-cast production process: every new format reaches different audiences and provides a different experience. I enjoyed imagining what Klara Klebanova looked like as she smuggled explosives under her skirts, or thinking of ways the surreal second act of The Dead Man could be staged. O’Brien is something of an Asch specialist: her translation of God of Vengeance has been mounted several times, including once as a COVID-era video production by Berkeley’s Yiddish Theatre Ensemble. I missed that production, a sign that we really are suffering an embarrassment of riches.

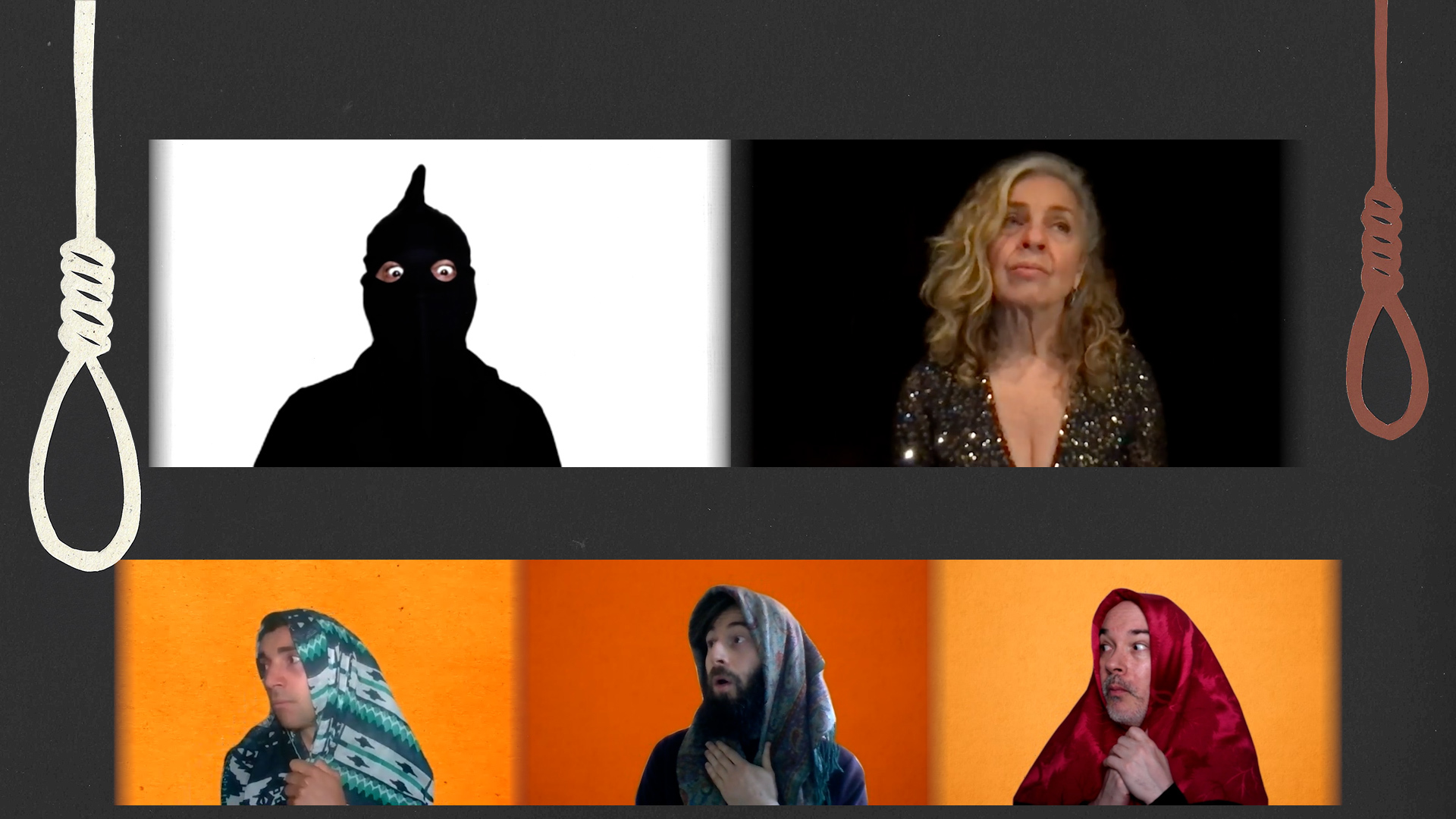

Scene from Megile-lider. Eleanor Reissa as Vashti. Courtesy of the Congress for Jewish Culture.

Scene from Megile-lider. Top: Shane Baker, Eleanor Reissa. Bottom: Josh Reuben, Noah Mitchel, Shane Baker. Courtesy of the Congress for Jewish Culture.

Scene from Megile-lider. Mike Burstyn as Akhashveyresh. Courtesy of the Congress for Jewish Culture.

Scene from Megile-lider. Daniel Kahn as Fastrigose. Courtesy of the Congress for Jewish Culture.

***

The extraordinary inventiveness of COVID Yiddish theatre has shown us what is possible for us in the post-COVID world too. Online theatre has proven to be able to create meaningful and engrossing experiences, far beyond the filmed stage productions that have been the main online theatre experience up until now. Here are some lessons we might want to take forward.

- Accessibility is crucial if we want to include our whole community. Online captioning makes a huge difference. Audio narration can be built in so the whole audience can benefit from it.

- Simple effects can be powerful effects. The Congress for Jewish Culture seems to be developing a “house style” of using shape-based images (historical wood cuts in one case; in another, contemporary papercuts by artist Adam Whiteman) for intertitles and scene transitions. These shapes stem from traditional Ashkenazic culture but are very suitable for online viewing. The Folksbiene’s darkening, blurring, and simple props do a lot of work without any pyrotechnics.

- Produce more diverse writers. Children’s plays, plays by women (and one day, we hope, non-binary folks), plays with challenging or philosophical scripts, and new material that questions old pieties—these will bring more life and new audiences to Yiddish theatre.

- Casting can be innovative. The Congress for Jewish Culture got the YidLife Crisis guys to appear in cameos: any time you bring together film, television, and live theatre people, you get a rich energy. A transgender actor in Blut un blintzes brought a fresh interpretation to her character.

- Different formats do different things. Use Zoom when you want to talk to your audience; YouTube Live to allow chats; Audio productions for text-heavy material.

- Experiment with traditional forms like puppet theatre and radio plays: they can enrich the mix.

- Continue to stream. Audiences are everywhere.