The Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible: A Commentary, Historical Background, Transcription, Translation by Jean-Marie Dodu.

[Paris]: Editions Les Incunables, 1985.

Call Number: (SPL)(FOL) Z 241 .B58 1985

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

The painstakingly transcribed manuscript Bible was a luxury item well beyond the grasp of the average man. However, the religious and intellectual turmoil of the fifteenth century Reformation produced a need to make the Bible, as the central text of Christianity, accessible to all Christians.

Significantly, the first known printed text from moveable type in the West was Johann Gutenberg's Bible, dated to around 1455. Through early experiments in metallurgy and manufacturing, he had recognized the profits in mass-production, and decided to apply these technologies to printing. The concepts of printing were known, and over a twenty-year period Gutenberg adapted existent press technologies to construct his printing press, adding an adjustable hand-mold to allow the precision-casting of thousands of letters. He also devised his own ink formula of oil paint with a high copper and lead content, which survives intact to this day. Indeed, Gutenberg's innovations were so effective that the basic principles of printing remain unchanged to this day.

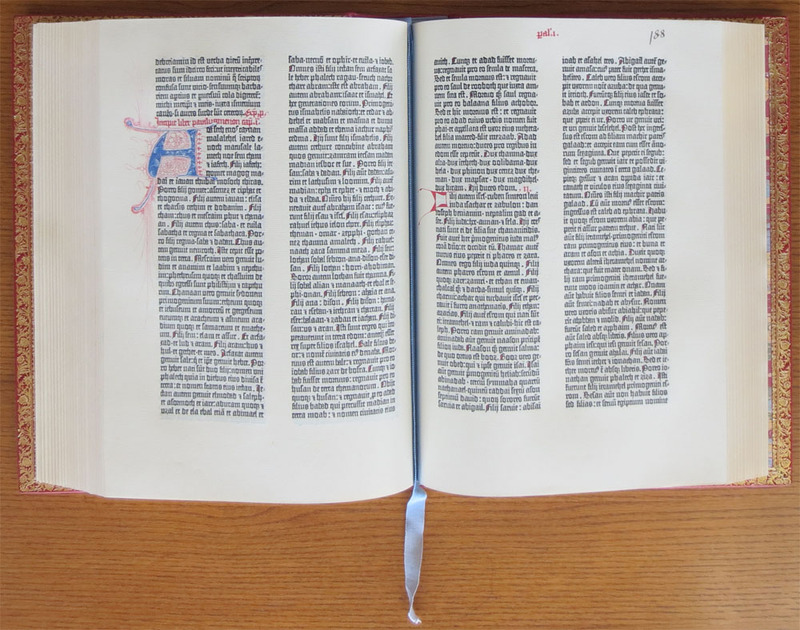

Gutenberg's Bible took six years to typeset and consisted of 643 leaves printed in double columns of large, closely woven type. It is alternately known as the "42-line Bible," for the number of lines of type in a column, or the "Mazarin Bible," for the seventeenth-century French cardinal who owned a fine copy. Although the work was printed, Gutenberg adhered aesthetically to accepted manuscript formats: types were modeled after local manuscript hands, spelling, punctuation, and abbreviations drawn directly from the medieval manuscript tradition, and hand-illumined initials and capitals were commissioned from Guild illustrators. Despite the nascent interest in home Bible study, Gutenberg adhered to the cumbersome folio format, realizing that to market the mass-produced Bible, his work must be comparable to the manuscripts produced by the scriptoria. As a sacred text, the Bible was expected to look a certain way, aesthetic inferiority could not be compensated by technological innovation.

Gutenberg's invention was not an immediate commercial success: the medieval manuscript tradition was considered inseparable from the sanctity of the text. Some believed the reproduction of identical Bibles to be diabolical; some early printers in Catholic cities were even martyred as heretics.

It has been conjectured that there were approximately two hundred copies of the Gutenberg Bible; twelve copies on vellum, and thirty-six on paper survive worldwide. Volumes one and two of this facsimile reproduce the Mazarin Library copy of the Gutenberg Bible, while volumes three and four transcribe the Latin, translate into English, and list all known copies of the work.