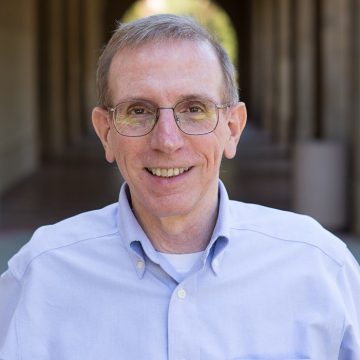

Display case at the Fundación IWO, Buenos Aires, with Jevel Katz’s portrait, his accordion, and sheet music for his “Ovinu Malkeinu” lampoon. Photo taken in May 1996.

“More Argentine than Martín Fierro”: Jevel Katz’s Debut in Buenos Aires, 1930

Zachary Baker

During the 1930s, Buenos Aires cemented its reputation as one of the capitals of Yiddishland. A thriving Yiddish-speaking public avidly patronized the newspapers, magazines, publishing houses, literary organizations, cafés, mutual aid societies, and philanthropies that sustained their community in spirit and in body. In addition, several Yiddish theatre companies vied for their patronage. A constant churn of stars visited from abroad, leading these troupes for weeks or months at a time. Under the guest artists’ direction, the theatres mounted a diverse repertory of operettas, comedies, melodramas, and literary classics. 1

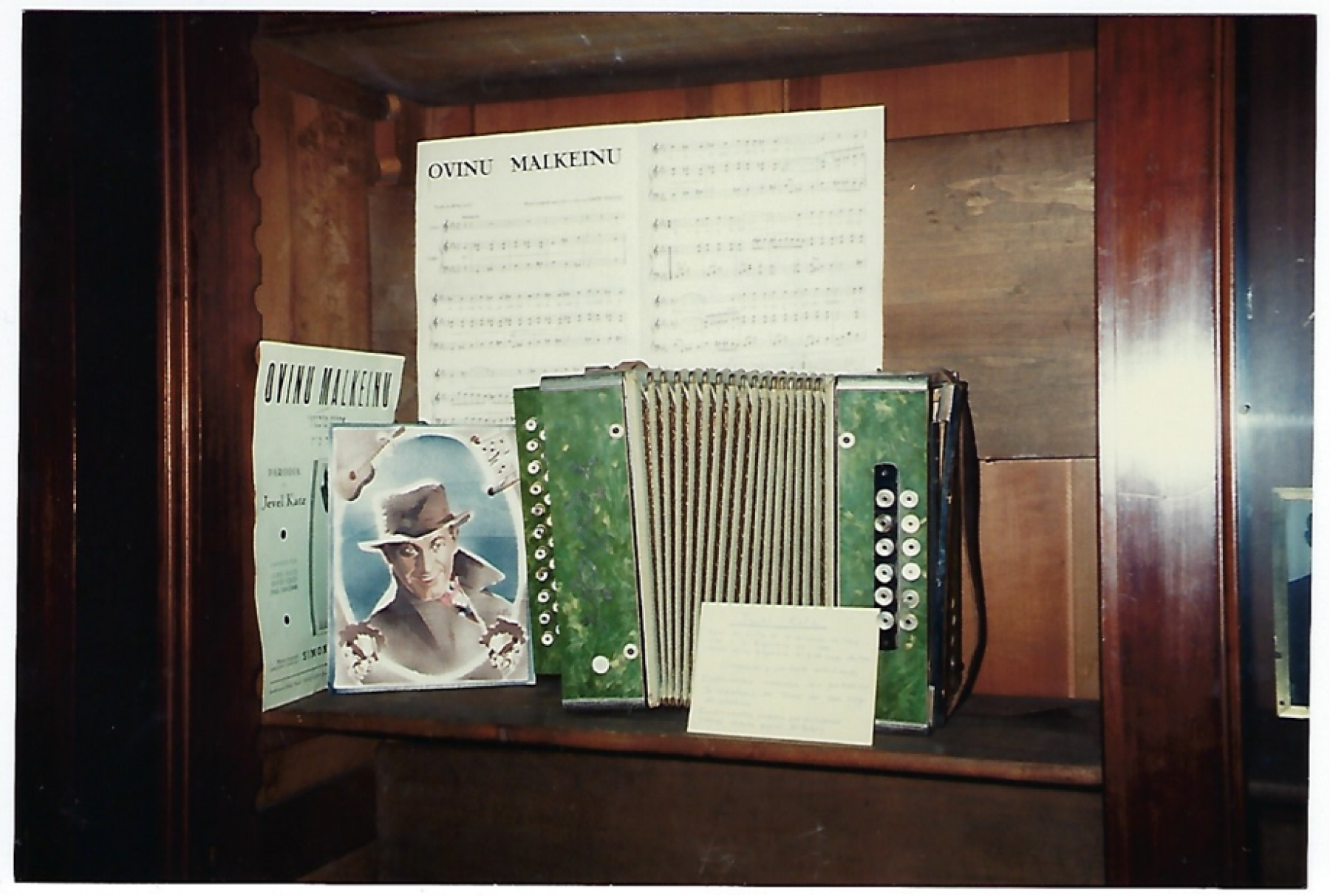

Jevel Katz arrives in Buenos Aires. Source: “A moderner idisher kupletist in Buenos Ayres: Khevl Kats,” in Di prese (Buenos Aires), June 6, 1930.

To the local critics, however, the glass was merely half full: they deplored the predominance of trashy North American melodramas and operettas over the “better,” more highbrow repertory; they lamented the paucity of productions of plays by Argentine Yiddish writers; and they continually lambasted the “star system,” which favored guests from overseas over homegrown talent. The critics acknowledged one exception to this latter complaint: the singer-songwriter Jevel (Khevl) Katz. He arrived in Argentina in May of 1930, at the age of twenty-eight, and quickly established himself as a hugely popular performer.

Alexander Vertinsky.

After Katz’s untimely death in 1940,

2

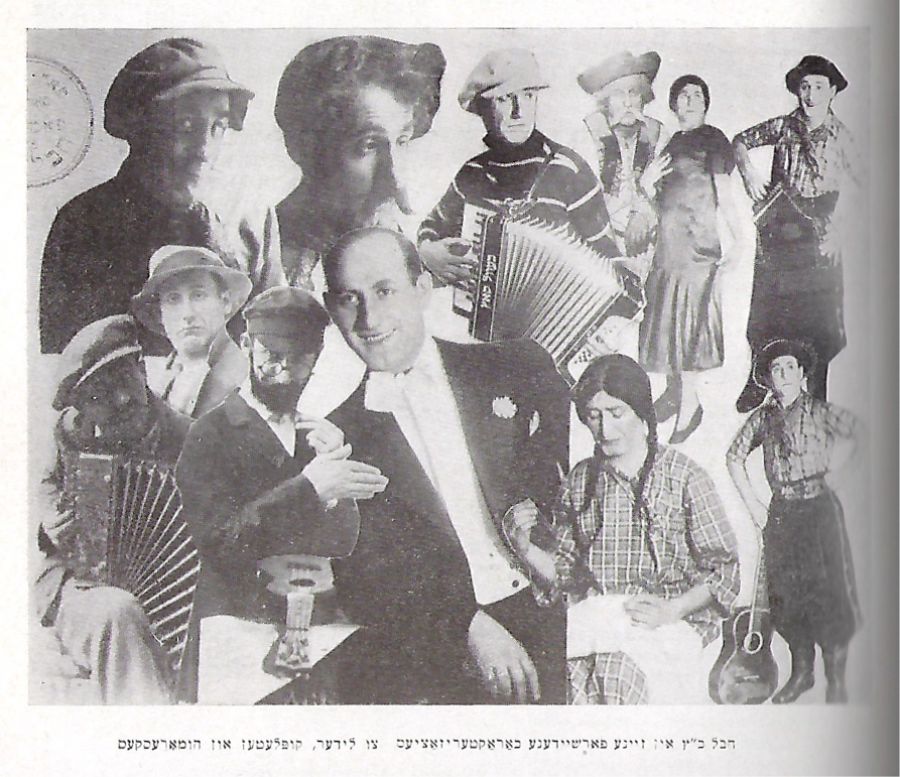

Shmuel Rozhanski (Samuel Rollansky) commented that Jevel Katz “was the only Argentine ‘star,’” with over 500 compositions to his credit, running the gamut from couplets, ballads, declamations, and children’s songs, to lampoons, impressions, satires, and parodies.

3

Arrayed in a variety of colorful costumes, accompanying himself on different instruments, and producing his own sound effects, this “cheerful Litvak” enchanted audiences young and old alike. His songs, often peppered with expressions in Spanish and the Buenos Aires lunfardo dialect,

4

draw the collective portrait of an immigrant community’s travails and foibles. Jevel Katz made only a handful of recordings; among these are the evocative “Mucho ojo,” conveying an immigrant’s struggles to adjust to the new land, and “Tucumán,” chronicling the singer’s train trip (replete with chugs and whistles) to a concert venue in the Argentine provinces. Some of his songs were posthumously recorded by other artists, among them “Ikh zukh a tsimer” (I’m Looking for a Room) and “Ovinu malkeinu,” a first-person account of a domino game, set to the melody of the solemn High Holy Day prayer.

5

Jevel Katz’s arrival in Argentina did not go unheralded. Just a couple of weeks after he landed there, the Yiddish daily Di prese ran a brief announcement of Katz’s forthcoming debut at a literary evening honoring the pioneering Argentine Yiddish writer Mordkhe Alperson (Marcos Alpersohn, 1860-1947), convened by the H. D. Nomberg Yiddish Writers’ Association. The announcement, titled “A Modern Yiddish Composer of Couplets in Buenos Aires,” featured a photograph of Katz in top-hat and formal garb, evoking one of his European musical idols (and parodic foils), the Russian singer Alexander Vertinsky (1889-1957). 6

The competing daily Di idishe tsaytung also ran a brief article about the freshly arrived kupletist. It featured this extract from an undated writeup in the Vilna Tog, which Katz shared with his Argentine interlocutors:

Jevel Katz … is a son of the Vilna streets. A typographer by profession, he has since childhood had a penchant for writing and composing ditties on local Vilna themes. These songs were so simple and folksy – and they possessed such a hearty folk humor – that they were inevitably a big hit among the intimate circles where Jevel Katz would sing them. About five or six years ago [circa 1924-1925], he performed for the first time before a larger audience and became very popular in Vilna. He owes his success with audiences not only to the texts and music that he has composed, but also to his renditions of them. He is musically talented, performing on various instruments, and his couplets—which he accompanies on guitar, harmonica, and other instruments—are highly original.

“Khevl Ka”ts, kupletist un parodist, in buenos ayres,” in Di idishe tsaytung, June 3, 1930. The Alperson event took place on June 7, 1930.

This, then, was the artistic toolkit that Jevel Katz brought with him to Argentina. He performed several of his couplets, parodies, and monologues for the staff of Di idishe tsaytung, and the paper duly vouched for their tastefulness and their authentically folksy character, while conveying Katz’s wish to perform them before a wider audience.

Katz opened his performance at the Alperson celebration with a humorous “autobiography,” followed by some “laughter couplets” (lakh-kupletn) and Yiddish parodies of three of Vertinsky’s songs. He brought down the house with his final number, “An umordnung in noz” (A Nasal Disorder), an amusing couplet that was punctuated by frequent sneezes. A reporter for Di prese wrote that in contrast to the less inventive song lyrics that were ordinarily encountered on the Yiddish stage, Katz’s couplets had “a point, a clear language, and a rhythm.” The journalist felt that the Vertinsky parodies went over the heads of many audience members but, overall, “the Buenos Aires [Yiddish] theatre has acquired a genuine talent.” 7

“Jevel Katz and various characterizations accompanying his songs, couplets, and humoresques.” Source: Shmuel Rozhanski (Samuel Rollansky), “Dos idishe gedrukte vort un teater in Argentine,” in Yoyvl-bukh: sakh-haklen fun 50 yohr idish leben in Argentine (Buenos Aires, 1940). This extensive essay was also published as a monograph in 1941.

The rival newspaper’s account of that event was glowing: “Regarding Jevel Katz, it can be truly said that he has come and he has conquered…Jevel Katz declaimed, he recited a monologue, and he acted with ardor and talent…A spicy line, a word—and the word is immediately accompanied by a playful act, a gesture, a laugh, a shout, a sigh, or a sneeze.” The article (probably by Rozhanski) concluded with an assessment and a prediction: “Jevel Katz possesses technique; his face sparkles while he sings or declaims, but with restraint—and avoiding exaggeration. He is an artist who, once he feels at home in our milieu and absorbs our way of life, will enrich Yiddish artistic life here.” 8

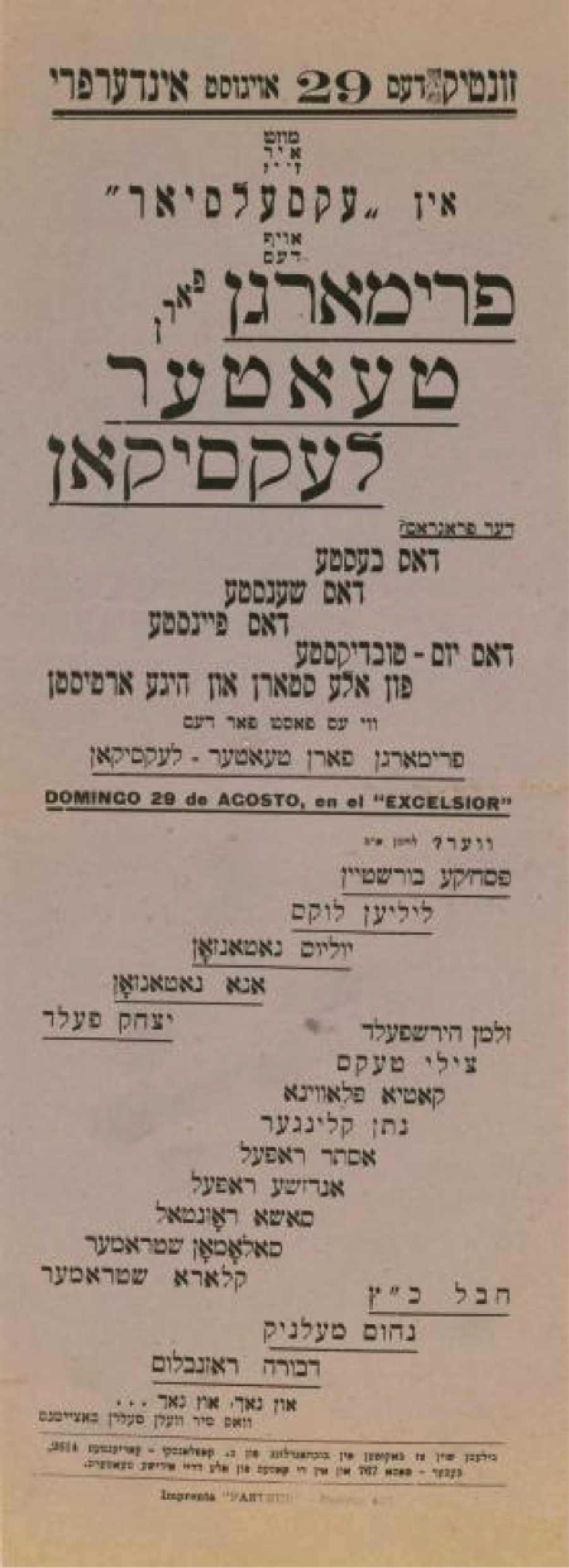

Announcement for a matinée honoring Zalmen Zylbercweig, who visited Argentina in 1937 to promote the publication of his Lexicon of the Yiddish Theatre. The headliners at the event included Pesach’ke Burstein and his wife Lillian Lux, visiting from New York. Jevel Katz’s name appears toward the lower righthand corner of the poster. Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Poster for a benefit matinée in support of the Ber Borochov Workers’ Schools, Buenos Aires, April 10, 1932. Jevel Katz, wearing a dinner jacket and white bow-tie, is shown by the center-right margin. Members of the Yidisher folks-teater company are pictured here as well. Source: Fundación IWO, Biblioteca Digital, Código A134.

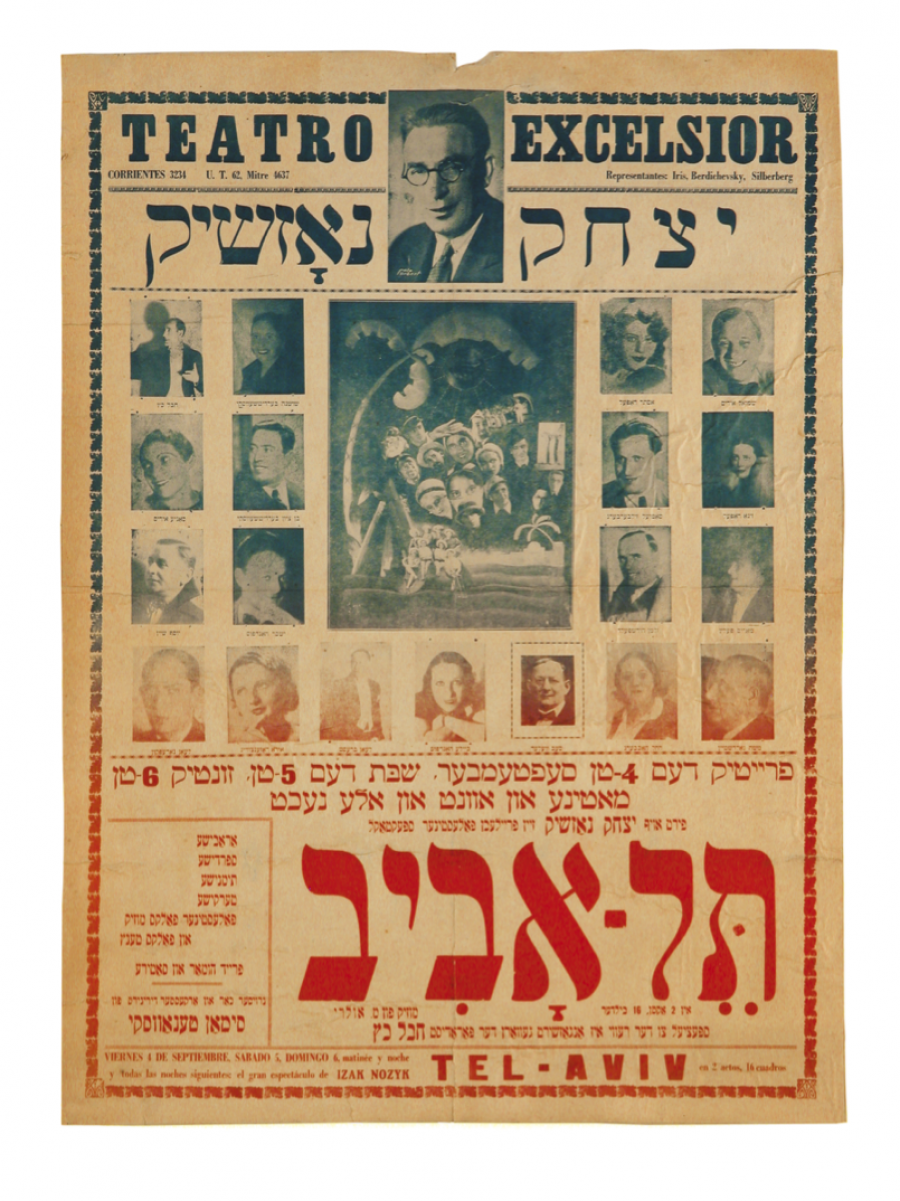

The Polish Yiddish actor-director Yitskhok Nozhik (Izak Nożyk) staged “Tel-Aviv,” a theatrical spectacle, at the Teatro Excelsior in Buenos Aires in September 1936. “The parodist Jevel Katz has been specially engaged for this revue,” the poster states. His photo appears in the upper left-hand corner of the Excelsior company’s roster of portraits. Source: Fundación IWO, Biblioteca Digital, Código A033.

Indeed, within the course of Jevel Katz’s first few months in Argentina, this prediction was already being borne out. The Yiddish press reported on several other performances of his—each within the framework of a larger cultural happening—which took place during the Argentine winter months of 1930. These outings reflected the linguistic, cultural, and artistic adjustments that Katz was progressively making to his new surroundings. And in some of the public events, Katz shared the stage with visiting luminaries of Jewish (and Yiddish) culture. For instance, in late June, the famous Yiddish actor-director Maurice Schwartz, visiting Buenos Aires for the first of many tours there, was honored at a festive luncheon. Sandwiched in among the many speeches and performances (including Schwartz’s own remarks to those assembled) Katz performed his lampoon of The Romanian Wedding, the hit comic operetta with music by Peretz Sandler and libretto by Morris Schorr – a genre that contrasted with the more literary fare favored by Schwartz.

9

The endless tributes and recitations at events such as this one would become the fodder for some of Katz’s gentle satires of the Yiddish scene in Argentina.

A few weeks later, “the well-known artist Jevel Katz” (as a newspaper announcement now labeled him 10 ) was among the performers at a benefit concert for Vilna’s Yiddish Scientific Institute (YIVO). The headliners were the Yiddish actors Samuel Goldenberg and Stella Adler—like Schwartz, on tour from New York. 11 There, for the first time, he sang two songs on local themes, which were warmly greeted by the audience: “Argentiner glikn” (Argentine Luck 12 ) and “Der griner bokher” (The Young Greenhorn). In addition, Katz performed his humorous autobiography, and yet again he stole the show with “A Nasal Disorder.” A reporter from Di prese commented, “His couplets make a pleasing impression and they are far from banal.” 13

Rounding out the cultural season, at the end of August 1930 Katz recited some of his by-now “well-known couplets” at a luncheon reception for the Polish-Jewish painter Maurycy Minkowski, visiting Argentina together with his brother Feliks and his wife Rachel Marshak (a fellow Vilner). 14

In succeeding years, Jevel Katz’s reputation and popularity would continue to grow. He was a ubiquitous presence on the Yiddish cultural scene, performing in plays put on by theatrical troupes, in radio broadcasts, at events organized by Jewish societies and schools, and in solo concert tours in and around Buenos Aires, other cities and agricultural colonies across Argentina, and neighboring Uruguay and Chile. The distinctively Argentine Yiddish persona and repertory that Katz created drew upon the rich musical, theatrical, religious, and literary traditions—Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian—that he had absorbed in the Jerusalem of Lithuania. 15 In the process, as the Argentine author and theatre commentator Marcos Rosenzvaig has put it, “He became more Argentine than Martín Fierro, without losing his identity.” 16 Jevel Katz’s name and his music live on in the memories of the Jews of Argentina.

Sources

Alexander Vertinsky, accessed September 22, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Vertinsky.

Baker, Zachary M. “‘Gvald Yidn, Buena Gente’: Jevel Katz, Yiddish Bard of the Río de la Plata,” in Inventing the Modern Yiddish Stage: Essays in Drama, Performance, and Show Business, Joel Berkowitz and Barbara Henry, eds. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2012), 202–222.

Jevel Katz, accessed: September 17, 2018, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jevel_Katz.

Jevel Katz y sus paisanos, director: Alejandro Vagnenkos. 2005. Video, 70 minutes, accessed, September 17, 2018, https://vimeo.com/35317861.

Palomino, Pablo. “The Musical Worlds of Jewish Buenos Aires, 1910-1940,” in Mazal Tov, Amigos! Jews and Popular Music in the Americas, Amalia Ran and Moshe Morad, eds. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2016), 25–43.

Rozhanski, Shmuel (Samuel Rollansky). “Dos idishe gedrukte vort un teater in Argentine,” in Yoyvl-bukh: sakh-haklen fun 50 yohr idish leben in Argentine; lekoved “Di idishe tsaytung” tsu ihr 25-yohrigen yubileum [Cincuenta años de vida judía en la Argentina: homenaje a “El Diario Israelita” en su vigesimoquinto aniversario] (Buenos Aires: 1940), 327-418. Separately published as vol. 1 of the author’s Gezamlte shrifn (Buenos Aires: 1941), which is accessible here: https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/yiddish-books/spb-nybc202123/rozshanski-shemuel-dos-yidishe-gedrukte-vort-un-teater-in-argentine.

Rosenzvaig, Marcos. “El teatro ídisch en Buenos Aires,” in Cuadernos de investigación teatral del San Martín 1 (Buenos Aires, 1994): 54–64.

Svarch, Ariel. “Der freylekhster yid in Argentine: The Life and Death of Jevl Katz, Popular Artist of the 1930s,” in Splendor, Decline, and Rediscovery of Yiddish in Latin America, Malena Chinski and Alan Astro, eds. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2018), 225–250. See also his article, “Mucho lujo: Jevl Katz y las complejidades del espectáculo étnico-popular en Buenos Aires, 1930-1940,” in ISTOR: Revista 53 (2013), 65–78.

Toker, Eliahu. ¡Andá a cantarle a Jevel Katz!, accessed: September 17, 2018, http://eliahutoker.com.ar/escritos/gente_katz.htm.

Zylbercweig, Zalmen. “Katz, Khevel,” in Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 7, 6163-6167.

Notes

-

1The number of professional troupes in Buenos Aires fluctuated from season to season—and sometimes, within each season, from month to month. At some points during the mid-1930s as many as five Yiddish theatre companies performed simultaneously in Buenos Aires, including the non-commercial, leftist Yidisher folks-teater (IFT). The Yiddish theatre flourished there into the 1950s, past the heyday of the Yiddish Rialto on New York’s Second Avenue.

-

2Katz succumbed to a post-operative infection following a tonsillectomy; the shock was such that upwards of 25,000 people lined the streets of Buenos Aires for his funeral procession in March 1940. For background on Jevel Katz, see Baker (2012), Svarch (2013 and 2018), and Zylbercweig (undated).

-

3Rozhanski (1940), 407 (emphasis in the original).

-

4The Argentine Jewish poet and critic Eliahu Toker labeled this language mixture castídish. For an extensive linguistic analysis of Katz’s song lyrics, see Svarch (2018).

-

5“Ikh zukh a tsimer” is sung here by Max Perlman (accompanied by Simón Tenovsky on the piano); “Ovinu malkeinu” is sung here by Max Zalkind. There is a playlist of songs by Jevel Katz, sung by him and by other performers, on YouTube, accessed October 3, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLTOAUUjhQKy4N4zJHMtieOuLrerrJV6gz. Most of these songs, along with scans of a couple of posters, are also accessible through the Fundación IWO’s Digital Library: http://www.iwo.org.ar/biblioteca/busqueda?Catalogo%5BTodos%5D=Jevel+Katz%7C1. Additional details concerning lyrics to some of these songs are found in my essay “‘Gvald Yidn, Buena Gente’: Jevel Katz, Yiddish Bard of the Río de la Plata” (Baker, 2012), and in Ariel Svarch’s 2018 essay.

-

6“A moderner idisher kupletist in Buenos Ayres: Khevl Kats,” in Di prese, June 6, 1930. Many of Alexander Vertinsky’s vintage recordings are accessible online via YouTube. His 1926 recording of the song “Dorogoi dlinnoyu” (“Endless Road,” composed by Boris Fomin with lyrics by the poet Konstantin Podrevskii) will ring a bell with today’s listeners. The English adaptation (lyrics by Gene Raskin), “Those Were the Days,” was recorded in 1962 by the Limeliters and became a big hit in Mary Hopkin’s 1968 rendition.

-

7“Der Mordkhe Alperson ovnt fun H. D. Nomberg Shrayber Fareyn,” in Di prese, June 9, 1930.

-

8“Der Alperson-ovend, organizirt fun Shrayber-Fareyn, hot gehat a groysen derfolg,” in Di idishe tsaytung, June 10, 1930.

-

9“Der kaboles-ponem fun ‘Shrayber-Fareyn H. D. Nomberg’ far Moris Shvarts,” in Di idishe tsaytung, July 1, 1930. “Di rumenishe khasene” had its premiere in September 1923, with Aaron Lebedeff and Bessie Weisman in the leading roles.

-

10“An interesanter frimorgn farn Idish visn. Institute,” in Di prese, July 21, 1930.

-

11As a Vilner, Katz would likely have been aware of YIVO’s work, including its assiduous collecting of Yiddish folklore.

-

12Argentiner glikn was the title of the only book or booklet to be published by Jevel Katz; it appeared in Buenos Aires in 1933.

-

13“Mit derfolg iz nekhten gevorn durkhgefihrt der “IVO’-frihmorgen,” in Di idishe tsaytung, July 28, 1930; “Der nekhtiker frimorgn fun der IVO,” in Di prese, July 28, 1930.

-

14The reception was sponsored by the Association of Polish Jews in Argentina. See, “A kaboles ponem lekoved dem kunst-moler H’ M. Minkovski un zayn familye in’m Poylish Idishen Farband,” in Di idishe tsaytung, September 1, 1930. It is quite likely that Katz was familiar with the painter’s works and his reputation—Minkowski exhibited in Vilna in 1922 and the painter met his wife in Katz’s hometown. Minkowski, who had been deaf since early childhood, would die in Buenos Aires in November 1930, run over by a car. Dozens of his artworks now belong to the Fundación IWO. For background on Minkowski’s 1930 visit to Argentina, see my article “Art Patronage and Philistinism in Argentina: Maurycy Minkowski in Buenos Aires, 1930,” in Shofar 19, no. 3 (2001): 107–119.

-

15In July 1939, Rozhanski offered the following summary of Katz’s European artistic influences and subsequent development as a performer in Argentina: “Jevel Katz, who came from Vilna to Buenos Aires ten years ago, conveying the artistic moods of a Vertinsky-style cabaret artist and the musical talent of a Wunderkind, adjusted to Argentina more rapidly than any other educated or uneducated immigrant. In Buenos Aires, he did not for a single instant forget Vilna, which was the source of a powerful relationship to culture, the stage, and the art of the stage. The further away he was from Vilna, the greater was the veneration with which he sang his hymn ‘Vilne, oy, Vilne, mayn heymele’ (Vilna, O Vilna, My Beloved Home). Yet his profound longing for the Old Country was bound up with an indescribable affection for his new home, Argentina. He loved the Argentine Jewish community like a mother, with all of its faults and weaknesses, and he celebrated the community ‘from head to toe’.” Shmuel Rozhanski (Samuel Rollansky), “Azoy zingt Khevl Kats,” in Di idishe tsaytung, July 9, 1939; quoted in Zylbercweig (undated), col. 6164. “Azoy zingt Khevl Kats” [What Jevel Katz Sings] was a weekly rubric in that newspaper during 1939 and 1940, both before and after Katz’s death in March 1940 (when it was renamed “Azoy hot gezungen Khevl Kats”). Each installment included the lyrics to and musical notation for a song by Jevel Katz.

-

16Rosenzvaig (1994), 59. Martín Fierro was the gaucho hero of the epic poem, “El Gaucho Martín Fierro,” by José Hernández (1834-1886). It was first published in two parts (1872 and 1879) and has been translated into over seventy languages.