Studies of the Occult

W. B. Yeats, 1865-1939.

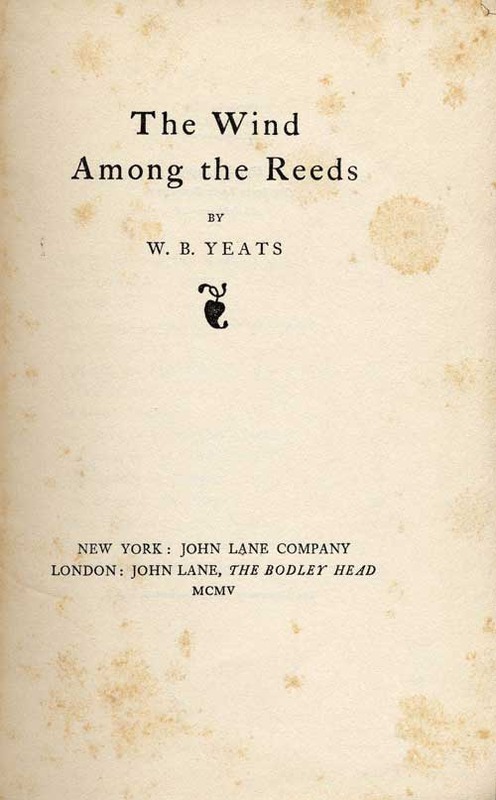

The Wind Among the Reeds.

London; New York: John Lane: The Bodley Head, 1905.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5904 .W6 1905

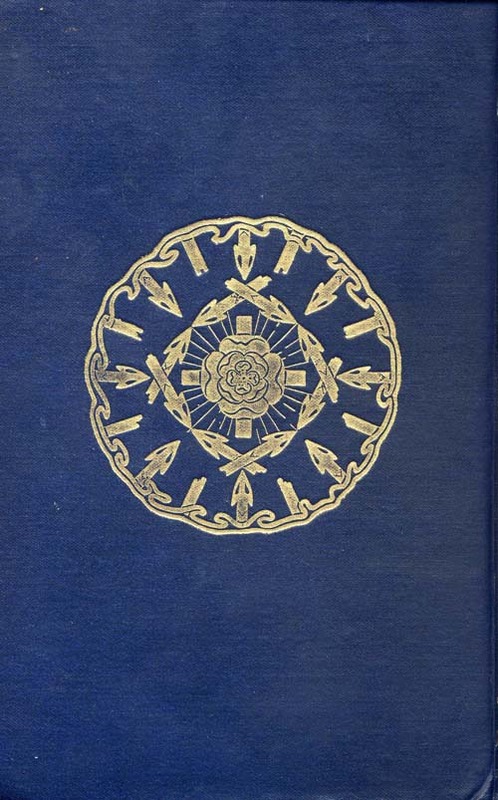

The Wind Among the Reeds, a collection of new poems Yeats had been working on for many years, was published in 1899 by John Lane in London. These American editions were printed at the University Press in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The stamped gold-foil designs on the blue cloth covers are the same as those of the first edition.

Many of Yeats’s concerns, including his study of the occult emerge in The Wind Among the Reeds. “The Fiddler of Dooney,” for example, contains imagery from the rites of the Golden Dawn: “helms of ruby and gold of the crowned magi.” “Into the Twilight,” written in 1893, reflects The Celtic Twilight, referring both to the birth of Ireland and the mystical hours of dawn and dusk.

Arthur Symons, 1865 -1945.

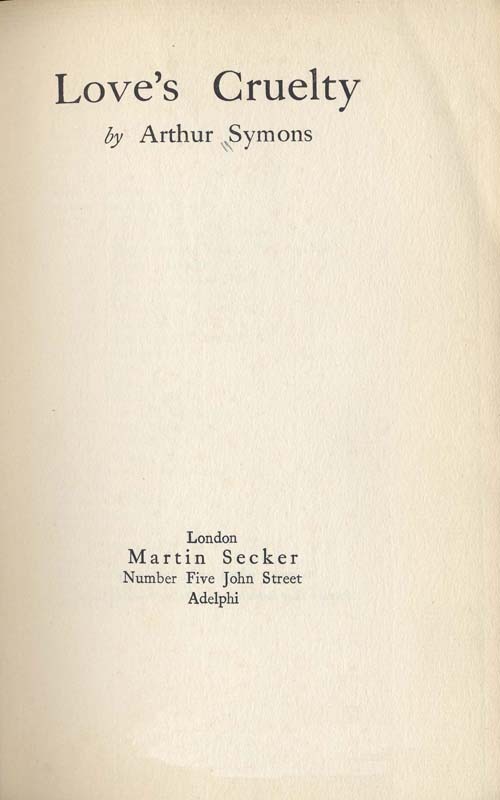

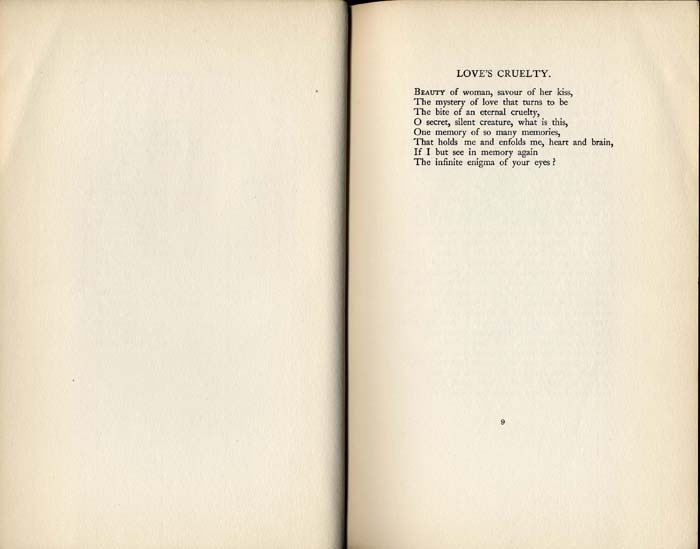

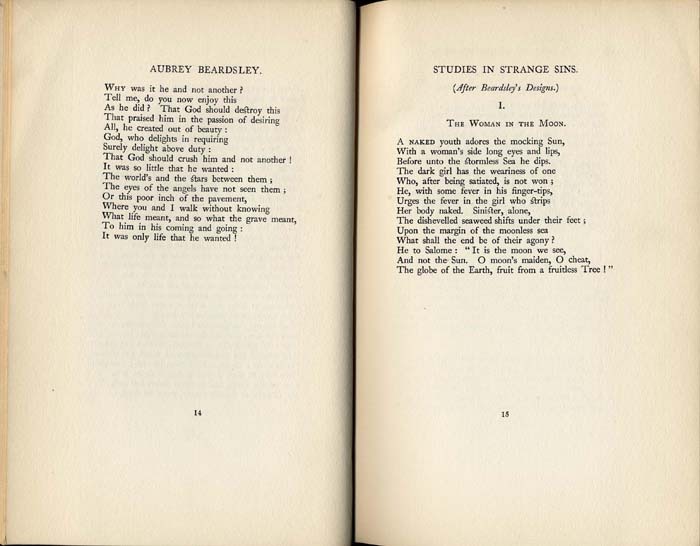

Love’s Cruelty.

London: Martin Secker, 1923.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5527 .L65

On the night in August 1856 that Yeats summoned his archer vision, Symons had a similar dream of “a woman of great beauty, but she was clothed and had not a bow and arrow.” Yeats was elated by the proof of occult phenomena Symons’ vision provided. Symons described his Tullyra vision in a poem entitled “To a Woman Seen in Sleep,” which remained unpublished until this 1923 collection of his poems Love’s Cruelty.

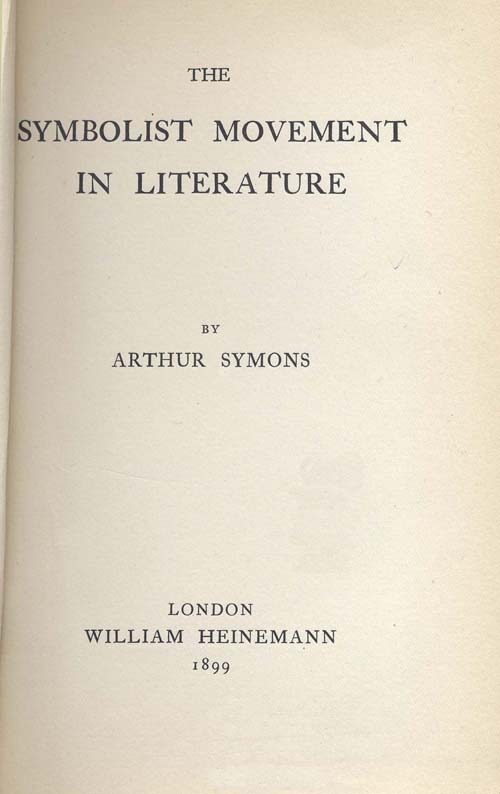

Arthur Symons, 1865 -1945.

The Symbolist Movement in Literature.

London: Heinemann, 1899.

(SPL) PQ 295 .S9 S8

Under the influence of Yeats and others in the 1890s, Symons moved more toward the symbolic and mystical schools of literature, of which Yeats was a proponent. His Symbolist Movement in Literature, which appeared in 1899, signals his spiritual transformation. It is both his most famous and most influential work. It was dedicated to Yeats. He addressed Yeats in the introduction as follows:

It is almost worth writing a book to have one perfectly sympathetic reader, who will understand everything that one has said, and more than one has said, who will think one’s own thought whenever one has said exactly the right thing, who will complete what is imperfect in reading it, and be too generous to think that it is imperfect. I feel that I shall have that reader in you; so here is my book in token of that assurance.

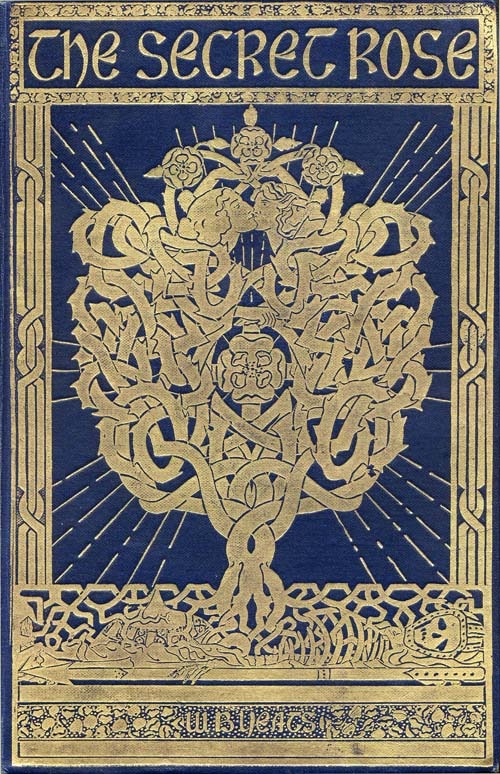

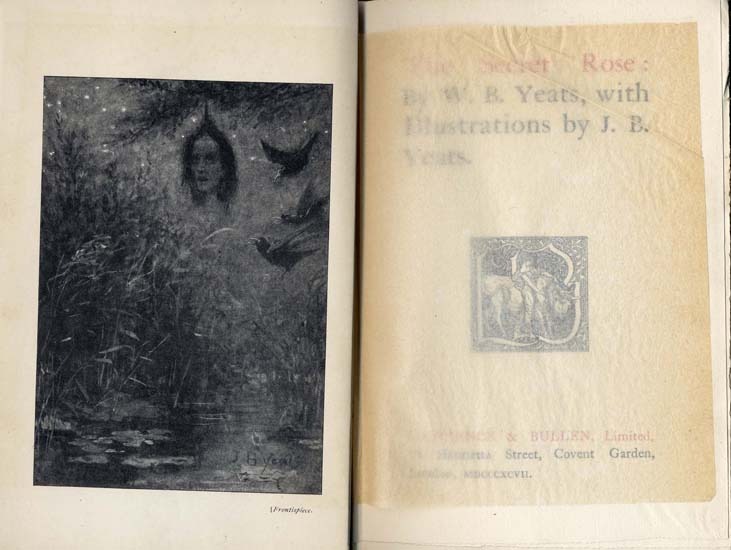

W. B. Yeats, 1865-1939.

The Secret Rose.

London: Lawrence & Bullen, Limited, 1897.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5904 .S3 1897

Illustrations by John Butler Yeats. Cover sign by Althea Gyles stamped in gold on covers and spine.

Throughout the nineties, Yeats was an avid student of mythologies and occult systems. These influences culminated in the composition of The Secret Rose. Yeats was reportedly near collapse as he finished the volume, a struggle to forge from these correspondences his own unique mythology.

The earliest elements of the book are the Red Hanrahan stories, originally published separately between 1892-6. Red Hanrahan is modeled on eighteenth-century Munster peasant poets and folklore figures Owen Rua O’Sullivan and William Dall O’Heffernan. Through successive versions of the stories, Yeats became more interested in Red Hanrahan’s occult and mythological significance, assigning increasingly visionary powers to his hero.

Other sections of the book had an overtly occult content, revolving around themes of excessive mysticism and apocalypse. “The Adoration of the Magi,” according to Yeats, was “a half prophecy of a very veiled kind.” Due to their frightening content, publisher Bullen omitted “Adoration of the Magi” and “Tables of the Law,” from The Secret Rose. The two poems were published privately in a separate volume later that year. “Rosa Alchemica” introduces Michael Robartes, a messianic occult figure modeled on MacGregor Mathers of the Golden Dawn, who would become a central figure in A Vision (1925).

W. B. Yeats, 1865 -1939.

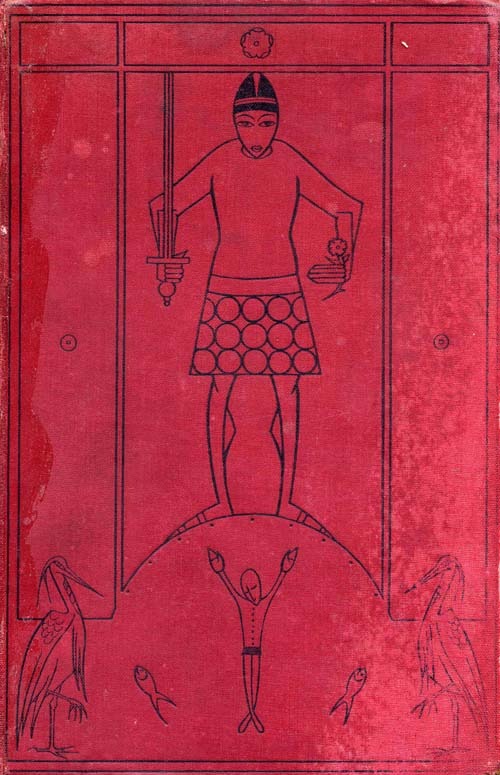

The Stories of Red Hanrahan and the Secret Rose.

Illustrated and decorated by Norah McGuinness. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1927.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5904 .S7x 1927

From 1903-5, Yeats undertook a revision of The Stories of Red Hanrahan with the assistance of Lady Gregory. The stories reappeared as a separate volume in a simpler language more appropriate to their oral origins. Revised successively for Yeats’s Works (1908) and Early Poems and Stories (1925), the stories were closely linked by symbolism to the Order of Irish Mysteries. Red Hanrahan was depicted as a figure within the Tarot, and an association was made between a magical pack of cards and the four sacred objects of Irish Mythology.

W. B. Yeats, 1865 -1939.

A Vision.

New York: Macmillan, 1938.

First printing. Published on February 23, 1938, 1200 copies.

Golda Meir Library

PR 5904 .V5 1938

Yeats long entertained an interest in clairvoyance; much of the teaching of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn had been received clairaudiently by MacGregor Mathers’ wife Moira. Four days after his wedding to Georgiana Yeats, the couple began to experiment with the automatic writing technique, through the mediumship of “George.” The automatic writing transcripts which they began on their honeymoon became a vast project, spanning 30 months and 450 locations worldwide.

Their research eventually encompassed “automatic speech,” communications uttered by George in sleep or trance. In total, 3600 pages of automatic script, several notebooks, two workbooks and a card file were generated.

The 1925 private subscription edition of A Vision was limited to 600 copies signed by the author. It subject was an exposition of a philosophical system explaining individuals and history in terms of the 28 phases of the moon. The work was so esoteric as to elicit little response, and Yeats embarked soon after on a major revision. In April 1928, he wrote to Lady Gregory that he was “at work on a final version of A Vision.” He continued to revise and expand the work until October 1937, fifteen months before his death.

A Vision laid out the whole of Yeats’s occult vision, much as Blake had done in his unpublished Vala, or the Four Zoas. Although the authenticity of the processes in writing the work are disputed, the work shows that Yeats’s interest in the occult was not merely a hobby but an all-encompassing framework for his work and life.

W. B. Yeats, 1865 -1939.

Later Poems.

London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1922.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5900 .F22

The lasting effect of Yeats’s occult influences of the nineties can be seen throughout his works. “The Second Coming,” perhaps the best known of his later poems, contains numerous references to his early work and philosophy. The poem refers to Spiritus Mundi, which Yeats defined in a note to Michael Robartes and The Dancer as “a general storehouse of images which have ceased to be a property of any personality or spirit.” The poem also refers to Magnus Annus, the history of epochs to which Yeats referred in his early apocalyptic works. The mythologies which form the basis of Yeats’s later poetry remain similar to the precepts set forth in “Magic,” an essay he published in 1901.