Celtic Folklore & Myth

W. B. Yeats, 1865 -1939.

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry.

Edited and selected by W. B. Yeats. London: W. Scott; New York: T. Whitttaker; [et. al.], 1888. (Camelot Series)

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PZ 8.1 .Y34 F

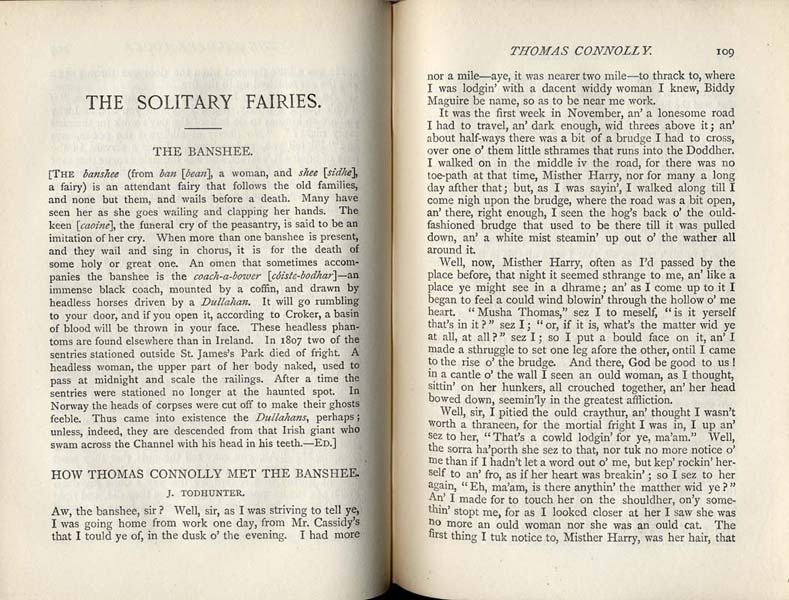

Yeats’s interest in Irish folklore began during his childhood in Sligo. Ernest Rhys, general editor of the Camelot Classics series, first contacted Yeats about preparing an edition of Croker’s Fairy Legends, but in July 1887 the project was changed to a selection of folklore. Yeats, hoping to find evidence of occult phenomena in the lore, read exhaustively from almost exclusively Irish sources. Finding previous collections obscured by stage-Irish mannerisms or overly scientific transcriptions, Yeats struggled to remain true to the tone and context of his sources.

Although some critics considered the compilation haphazardly assembled, the carefully researched introductions and bibliographic notes in the early sections of the book demonstrate the care with which Yeats approached his work.

Yeats was disappointed by the lack of occult phenomena in the material. Still, a combination of folk and occult themes, based in the visionary propensities of the Irish peasantry, became a dominant feature of his later writings.

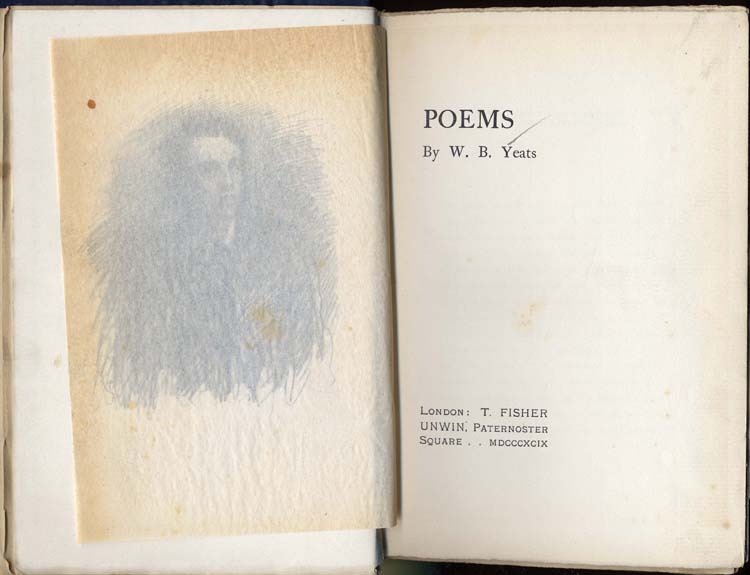

W. B. Yeats, 1865 -1939.

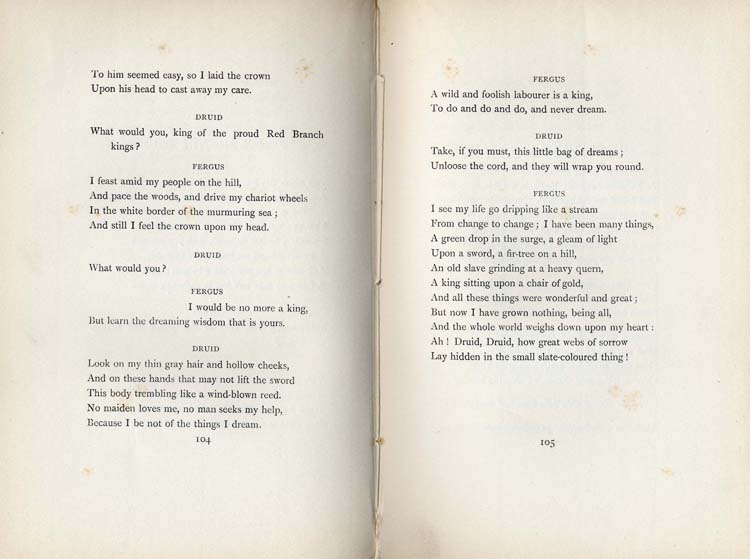

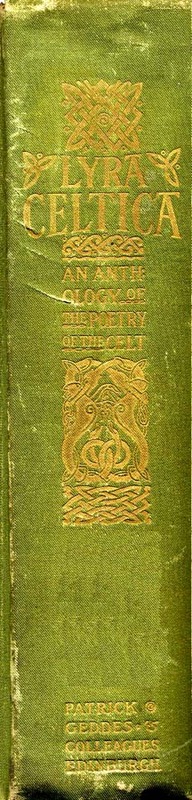

Poems; by W. B. Yeats.

Second edition, revised. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1899.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5904 .P6 1899

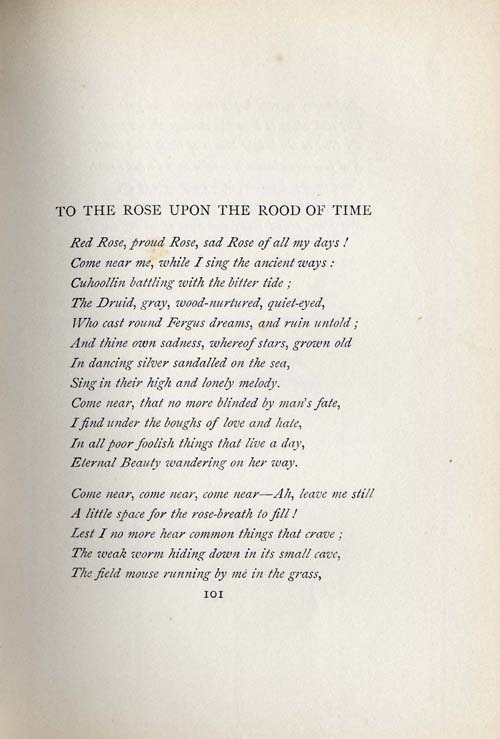

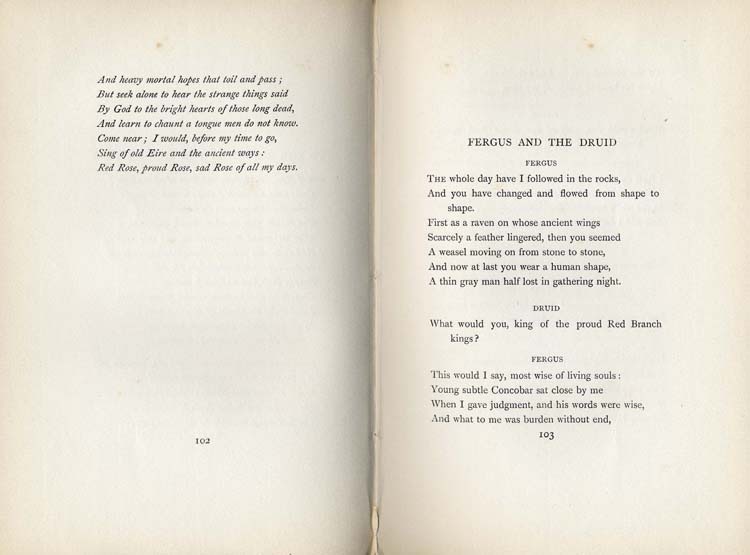

Yeats was only thirty when Fisher Unwin published the first edition of his collected poems in 1895. For the collection, Yeats spent three months rewriting pieces from his earlier books of poetry The Wanderings of Oisin and Countess Cathleen, striving to remove both non-Irish influences and “trivial” fairy verses. Only two new works were added; the play Land of Heart’s Desire and the dedicatory poem, “To Some I Have Talked to by the Fire.” Poems contains the works Yeats wished to preserve in 1895. They depend on a set of supernal symbols centered on that of the rose.

The poem “The Wanderings of Oisin” was singled out by William Sharp in his introduction to Lyra Celtica as an example of legend in modern Celtic poetry; Oisin may be directly traced to numerous sources in Irish myth. In a letter to Katharine Tynan, Yeats revealed the poem to be a veiled occult account: “In the second part of Oisin under disguise of symbolism I have said sever[a]l things, to which I only have the key. The romance is for my readers, they must not even know there is a symbol anywhere.” Oisin may be read as a story of rebirth or reincarnation, reflecting Yeats’s struggle to link ancient Irish myth with occult doctrines.

“The Countess Cathleen” was produced on May 8, 1899 by the Irish Literary Theater from an acting edition printed from the plates for this 1899 edition. Changes written onto the actors’ copies by Yeats appeared in the 1901 third edition of Poems.

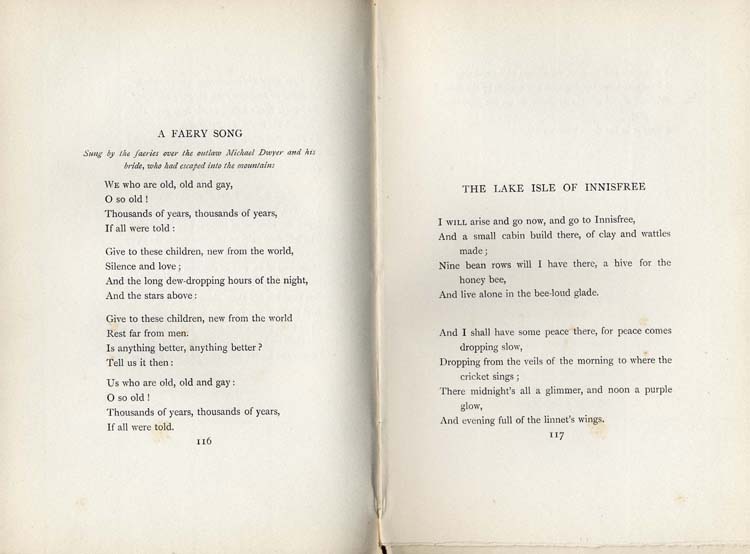

W. B. Yeats, 1865 -1939.

The Celtic Twilight.

London: A. H. Bullen, 1902.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PR 5904 .C4 1902

The Celtic Twilight reflects a major concern of Yeats in the 1890s. As the Irish oral culture was declining at the end of the century, Yeats recognized the importance of preserving the folk stories he had heard as a boy in County Sligo. He was particularly interested in visions and ghost-lore, which paralleled his occult beliefs. The title of this volume of stories and essays demonstrates Yeats’s familiarity with the ideas of Ernest Renan and Matthew Arnold. Yeats had called his review of Lady Wilde’s Ancient Curses, Charms and Usages of Ireland (1890), the “Tales of Twilight.” The phrase Celtic Twilight referred to the hours before dawn when Druids performed their rituals, an affirmation of Yeats’s belief in magic as a tool to open the Celtic past.

In the 1893 first edition of Celtic Twilight, Yeats transcribed the oral sources, inserting his own visionary experiences as “commentary” within the narrative. During his historic trip to Tullyra Castle in 1896, Yeats became close friends with Lady Gregory who lived nearby in Coole Park. That friendship led to their cooperation in collecting and compiling folklore in County Galway and then to their joint efforts to establish the Irish National Theatre. Some of the material Yeats and Lady Gregory collected in 1897 and later was added to this 1902 edition of The Celtic Twilight.

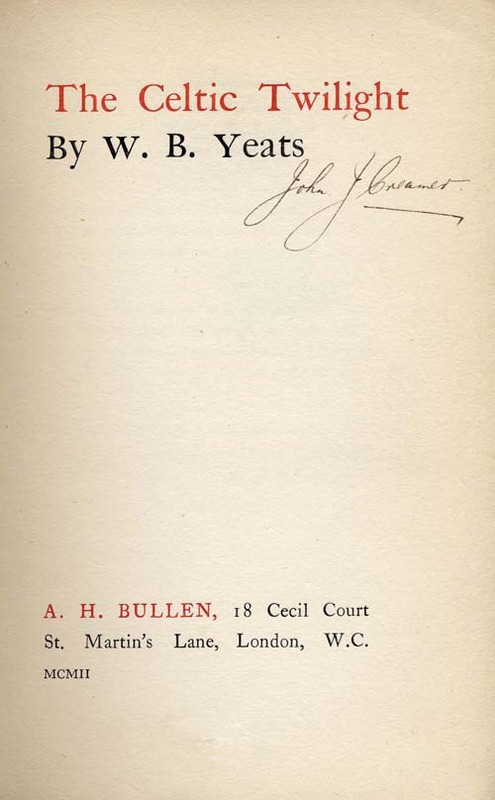

Elizabeth Sharp, 1856-1932, editor.

Lyra Celtica; An Anthology of Representative Celtic Poetry.

The Celtic Library. Patrick Geddes & Colleagues. The Lawnmarket, Edinburgh. 1896.

Special Collections, Golda Meir Library

(SPL) PB 1100 .S6 1896

From the collection of Margaret Culkin

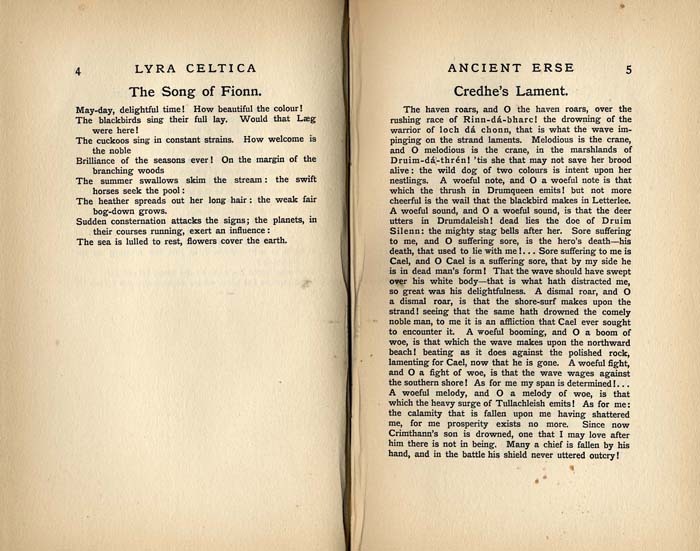

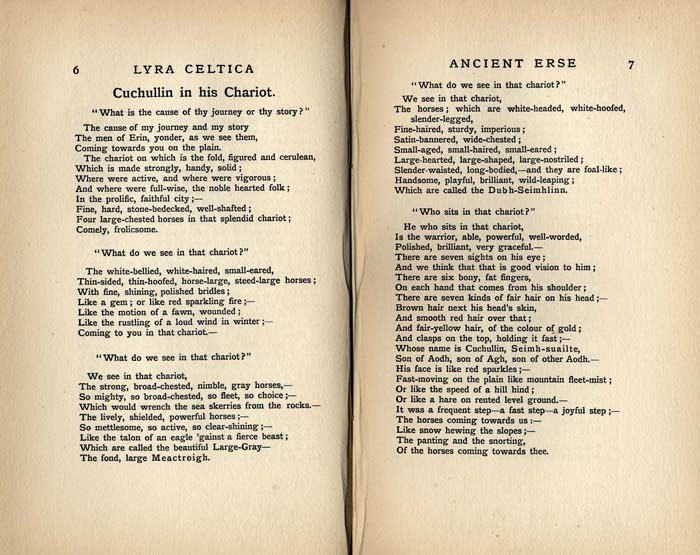

Lyra Celtica was marketed as a scholarly collection of Celtic literary material, and William Sharp’s lengthy, annotated introduction and notes advanced him as an authority in the pan-Celticist movement. Seven Fiona Macleod poems are included in the “Modern and Contemporary Scoto-Celtic” section. Three poems by Yeats are included in the “Irish (Modern and Contemporary)” section.

Following William Sharp’s elaborate praise of Yeats in his introduction to this volume, Yeats and Sharp became close friends in the summer of 1896. And Yeats became increasingly intrigued by the writings of Fiona Macleod and her personality as Sharp projected it to him. In writing to William Sharp about Lyra Celtica, Yeats praised the poems of Fiona Macleod it contained, particularly “The Prayer Woman.”

Sharp closed his introduction to Lyra Celtica with the idea of a Celtic “racial memory:” “The Celt falls, but his spirit rises in the heart and the brain of the Anglo-Celtic peoples, with whom are the destinies of the generations to come.” This theory was similar to Yeats’s Anima Mundi and Spiritus Mundi. Their shared interest in Celtic mysticism sparked a lengthy correspondence among Yeats, Sharp, and the pseudonymous Macleod.